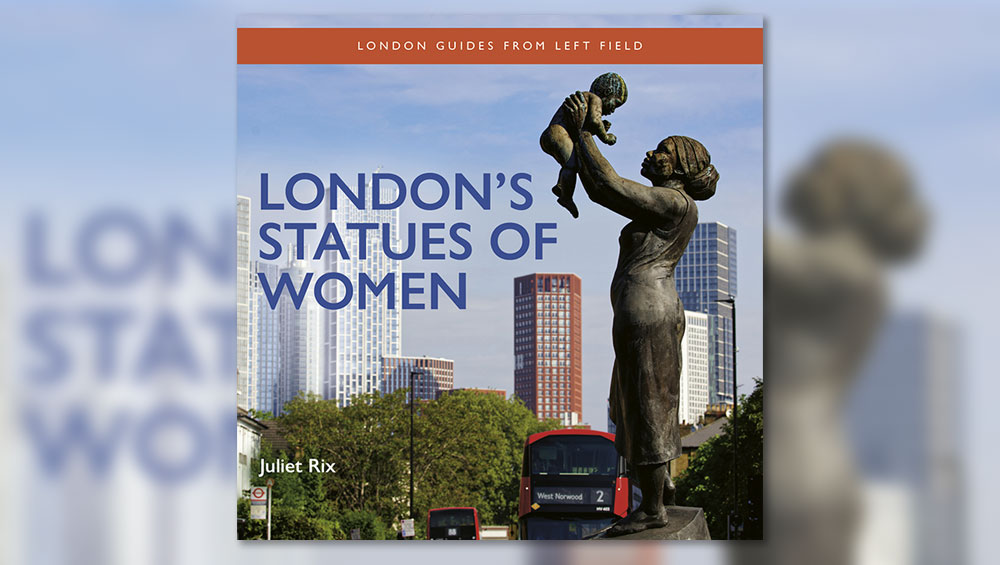

London’s Statues of Women by Juliet Rix, published by Safe Haven Books.

reviewed by ANNA McNAY

“It has been said you can judge a society by its public statues,” notes the author Juliet Rix in her introduction to this little gem of a handbook to London’s statues of women. Indeed, she continues by sharing the statistics, found in a 2021 survey, that, at that time, just one in six of London’s statues commemorating a named individual was for a woman. In 2022 and 2023, more statues of women than men were installed, and 2023 alone welcomed five new statues of individual women. Since then, the ratios have once again become less favourable, but the balance has at least been tipped.

Ada Lovelace by Mary and Etienne Millner, 2022. Bronze. Millbank Quarter, Horseferry Rd, Westminster, junction with Dean Bradley St. Photo: Rod Standing.

Organised alphabetically by first name, from Ada Lovelace to the Women of World War II, this book introduces a motley crew of statues – although the organisation here is clear and logical – some with more artistic value, some more lovable for their story, and some historically significant for the achievements of the sitter or of the statue itself (for example, see the “chronology of statues of colour” section, which lists a number of firsts in terms of black, Asian and minority ethnic statues). As well as this chronology, the roll call is interrupted by interviews with artists (for example, Maggi Hambling and Gillian Wearing) and sitters (for example, Alison Lapper of Fourth Plinth fame and Joy Battick, the sitter for the first public statue of a woman of colour in London), as well as by spotlights on artists (for example, Henry Moore), issues (for example, nudity) and muses/characters (for example, Britannia, Justice, Victory and so on). There are also some enjoyable authorial opinions and anecdotes (such as Rix’s discovery that the almost ethereal sculpture, The Awakening, 2002, by Unus Safardiar, in Regent’s Park, is a tribute to Dr Anne Evans, a friend of her mother).

Virginia Woolf by Laury Dizengremel, 2022. Full-length statue on a bench, bronze. Richmond Riverside. Photo: Juliet Rix.

The statues in this book range from those I know fairly intimately to those of which I was blissfully – and sometimes shockingly – ignorant. Well I knew the drawn and somewhat ghostly bronze bust of Virginia Woolf (2004, copy of 1931, by Stephen Tomlin) in Tavistock Square, but I was unaware of the full-length seated statue on a bench by the Thames in Richmond (2022, Laury Dizengremel), and somehow, through lack of looking up, the magnificently golden Three Graces or Daughters of Helios “diving” from the sixth-storey roof of the Criterion Building at Piccadilly Circus had also escaped my notice. Another revelation was that all – yes, all – of the the National Gallery’s architectural statuary is female – including bare-breasted figures on a horse and a camel representing Europe and Asia respectively and two winged figures personifying Painting, which are basically just Victory with a paintbrush and palette instead of a spear. These figures were originally intended for Marble Arch but ended up on the building in Trafalgar Square – somewhat ironically, given the paucity of works by female artists owned by the gallery.

The Three Graces or Daughters of Helios by Rudy Weller, 1992. Gilded aluminium. Criterion Building, Piccadilly Circus, corner of Haymarket. Photo: Juliet Rix.

There are a fair few entries depicting queens, including also a tirade by George Bernard Shaw against the various statues of Queen Victoria, which, in his opinion, represent her as “an overgrown monster”. There are also the four queens on the Kimpton Fitzroy hotel in Russell Square, which I hadn’t spotted, but here, I am more intrigued by one of Rix’s “also of note” comments, namely that there is a blue plaque on the Bernard Street corner of the hotel marking the site of the London home of the Suffragette Pankhursts before the hotel was built. Emmeline Pankhurst’s statue (1930, by Arthur George Walker) is, of course, included, the campaign for which began just two weeks after her death in 1928 – a fact that stands in stark contrast to the 2018 monument to Millicent Fawcett (by Gillian Wearing), Pankhurst’s contemporary, but a pacifist Suffragist as opposed to a militant Suffragette, who was made to patiently wait almost 90 years for her statue.

Emmeline Pankhurst by Arthur George Walker RA, 1930, with memorial relief to Christabel Pankhurst added 1958–59. Victoria Tower Gardens, Westminster. Photo: Juliet Rix.

Some militancy would perhaps be warranted in the case of Marc Quinn’s statue of Alison Lapper Pregnant, which stood on the Fourth Plinth at Trafalgar Square from 2005-07. Due to congenital phocomelia, Lapper was born with no arms and very short legs. Since 2020, this impressive marble work has been seeking a permanent public home. Quinn says it has been turned down across New York for being “too controversial”. Lapper says: “I can’t believe that in this day and age we are still so uncomfortable with difference,” adding: “everyone seems to forget that Nelson only had one arm and one eye (I’ve got two eyes!), but because he lost them in war, that’s OK.”

Left: Mary Wollstonecraft by Maggi Hambling, 2020. Bronze (coloured silver). Newington Green. Right: detail. Photo: Juliet Rix.

Of course there are other controversies, not least surrounding Hambling’s Mary Wollstonecraft (2020), which the feminist writer Caitlin Moran lambasted in a tweet, saying: “Imagine if there was a statue of a hot young naked guy ‘in tribute’ to eg Churchill …” Hambling was quick to defend the statue’s nakedness, saying simply that clothing a statue confines it to a specific period of time – as indeed is evidenced by Nathaniel Hitch’s stone statue of St Ethelburga (1892-95), which has been criticised by the history officer of All Hallows by the Tower, where it is sited, for having “wildly inappropriate” clothing from entirely the wrong century. Hambling further claims her work to be a statue for Wollstonecraft, not a statue of her; it is, she says, a statue of “an idea”, “an everywoman” rising from a mass of “mingling female forms”, representing the struggle from which Wollstonecraft and feminism emerged.

Sarah Siddons White by Léon-Joseph Chavalliaudt, 1897. Marble. Paddington Green. Photo: Juliet Rix.

The book also busts the myth that the statue of Florence Nightingale (1915, by Walker, who also sculpted Pankhurst) was the UK’s first of a non-royal woman (she is, however the UK’s most commemorated non-royal woman) – this is an honour to be held by the actor Sarah Siddons (1897, by Léon-Joseph Chavalliaud). The first statue of a real woman of colour, Joy Battick, as mentioned, appeared only in 1986, as one of three statues entitled Platforms Piece, by Kevin Atherton, standing on the overground platforms at Brixton Station (the other two are of a white woman and a black man). Joy I, as she is now known, was restored and joined by Joy II in 2023, also by Atherton, just after Battick had received treatment for breast cancer.

Joy II by Kevin Atherton, 2023. Bronze. Brixton Station (National Rail, above Brixton. Photo: Juliet Rix.

Katie by James Butler, 1987. Bronze. Station Rd, corner of St Ann’s Rd, Harrow. Photo: Juliet Rix.

Several pages are given over to the uncategorisable, “ranging from playful nudes to arty abstractions, nearly ‘normal people’ to fictional/poetic personifications,” including James Butlers’ whimsical skipping girl in Harrow town centre (Katie, Station Rd, 1987); Sean Henry’s larger-than-life and colourful Standing Woman (2020), with arms crossed and skinny jeans, at Canary Wharf; and Frank Dobson’s somewhat weightier (in both senses of the word) London Pride (designed 1951, cast in bronze and installed 1987), outside the National Theatre, commissioned for the 1951 Great Exhibition as a symbol of British achievement and optimism after the second world war, depicting two chunky female nudes holding a bowl that was intended to be planted with the flower London Pride.

-JR.jpg)

Standing Woman by Sean Henry, 2020. Canary Wharf (George St, Wood Wharf). Photo: Juliet Rix.

London Pride by Frank Dobson. Designed 1951, cast in bronze and installed 1987. Queen’s Walk, South Bank. Photo: Juliet Rix.

While I had heard of the Eleanor Crosses, I didn’t quite realise the full story, so was pleased to read more about them, too. When Eleanor of Castile died, her husband, King Edward I, had these memorial statues built across England. The last one was constructed in what was then the hamlet of Charing – which accordingly became Charing Cross. Today, we see a Victorian reconstruction of the 13th-century original, created when the station opened. What really interested me, however, was the fact that the statue originally stood at the top of Whitehall, where the equestrian statue of King Charles I now stands, and was the official centre of the capital, from where mileages to London were (and are) measured. In my head, this had, of course, originated with the statue of Charles, not his female predecessor. I am glad to have been put right.

Noor Inayat Khan by Karen Newman , 2012. Bronze. Gordon Square Gardens. Photo: Juliet Rix.

A rather beautiful and endearing bust is that of Noor Inayat Khan (2012, by Karen Newman) in Gordon Square Gardens. Khan was a spy in the second world war, who was tortured and shot in Dachau. Newman used to make wax statues for Madame Tussauds, which perhaps explains the depth of her tenderness and gentle detail.

Golders Hill Girl by Patricia Finch, 1991. Bronze. Golders Hill Park. Photo: Juliet Rix.

Another delicious “also of note” is attached to the entry for Queen Charlotte, and it reads: “In Queen Square is Sam (the Cat), a memorial to Patricia Penn, a local nurse, activist and cat lover who in 1971 campaigned to save Queen Charlotte’s Hospital.” Another good anecdote goes with Golders Hill Girl (by Patricia Finch, 1991), who had one of her seemingly kicked-off bronze flipflops stolen in 2003 and now owns the most expensive pair in town, valued at £1,000 by the foundry that remade them.

Susanna Wesley by Simon O’Rourke, 2022. Red cedar wood. East Finchley Methodist Church. Photo: Juliet Rix.

Perhaps the most unusual entry is the carved statue of Susanna Wesley, “the Mother of Methodism” (2022, by Simon O’Rourke), which emerges, totemically, from the trunk of a red cedar tree, pointing the way into East Finchley Methodist church, the non-conformist church her sons founded.

Amy Winehouse by Scott Eaton, 2014. Bronze. Stables Market, 407 Chalk Farm Road, Camden. Photo: Juliet Rix.

Other statues include Boudica (1856-83, erected 1902, by Thomas Thornycroft, on the north side of Westminster Bridge), Twiggy (2012, by Neal French, on Bourdon Place in Mayfair – depicted being photographed by a statue of Terence Donovan and watched by one of a woman with a number of boutique shopping bags), Mary Poppins (2020, by Samantha Wild, one of the only two women, along with Wonder Woman, among 12 statues comprising Scenes on the Square, an installation of film characters in Leicester Square) and Amy Winehouse (2014, by Scott Eaton, in Stables Market – Camden council waived its usual rule that people must have been dead 20 years before a memorial). There are so many more I could mention, and, as with any anthology, there is bound to be something here to please everyone. To experience the statues in the flesh, Rix provides three suggested walking “safaris”, which I look forward to trying out, if I don’t draw up my own itinerary based on my new learnings. While I’m not wild about the square format of the book, it is small enough to be fitted easily into a bag when heading out in the capital, and while the photography could be better, I appreciate the difficulty of getting decent images of many of these statues in situ. For that there is only really one solution: get out there and see them for yourself! (And get yourself a copy ready to take with you, so that you can be fully in the know!)

• London’s Statues of Women by Juliet Rix is published by Safe Haven Books, price £16.99.