Julian Perry. Photo: Sally Taylor.

by DAVID TRIGG

Uprooted trees, collapsed buildings and caravans teetering on clifftops all feature in the disquieting landscape paintings of Julian Perry (b1960, Worcester). But these scenes of destruction and loss do not depict the aftermath of an earthquake or a military conflict; Perry’s subject is the devastating impact of coastal erosion. For the London-based artist, Britain’s eroding shorelines and rising sea levels are emblematic of a world in crisis, pointing to the looming spectre of widespread climate breakdown. This is the pressing concern at the heart of his current exhibition at Southampton City Art Gallery, There Rolls the Deep, an impassioned response to environmental catastrophe and the relentless power of the cruel sea. Studio International spoke with Perry about his concerns regarding coastal erosion and climate chaos, his approach to landscape painting and his infatuation with Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-16), which has inspired his own secular interpretation conceived especially for Southampton.

Perry resolved to become an artist at the age of 15, going on to study at Bristol Polytechnic between 1978 and 1981, but his earliest introduction to painting came through his grandfather. “He was a theatrical set painter,” he says. “I used to sit on the stage while he painted the huge backdrops for the Festival Theatre in Malvern. He used to give me paint to play with and even taught me some techniques.”

Julian Perry: There Rolls the Deep. Installation view. Photo courtesy Southampton City Art Gallery and Julian Perry.

As an adult, Perry developed his highly polished figurative style by intently studying the landscape paintings of artists he most respected, in particular John Constable, Peter Paul Rubens, JMW Turner and William Dyce, whose works greatly influence his own. “It’s about wanting to create spaces that the imagination can move around in,” he says of his love for the landscape genre. “That capacity of a painter to take a flat surface and create little worlds within it fascinated me as a very young child, and still does. I like the simple idea that I am an artist who takes coloured mud and creates the illusion of all sorts of things by application of a little bit of skill.”

Perry is a painter of our often uneasy relationship with the natural world. Whether painting east London allotments about to be bulldozed as part of the Olympic Park development, an Epping Forest pond in a crater formed by a wartime V-2 rocket, or grim tower blocks surrounded by trees and fields, environmental issues have been central to his practice for years. More recently, the themes of coastal erosion and climate change have come to the fore. “Coastal erosion is profound because it annihilates; the sea takes everything away,” he explains. “It will destroy forests, houses and hotels, second world war defences, you name it; if you take the earth away there’s nothing left. When I first started to visit sites of coastal erosion, I expected to see lots of ruined buildings and a sense of destruction but, in 90% of the places, there’s nothing there but the cliffs.”

Julian Perry. Sea View Caravans, 2009. Oil on panel, 46 x 34 cm. Photo courtesy Colin Mills and Julian Perry.

The focus of Perry’s recent works has been erosion on the East Anglian coast, an area he has been visiting since childhood and which has become an important locus of climate change engagement. “I’ve got a house on the coast at Dunwich, the little Suffolk village that Turner painted, and which is now referred to as the capital of coastal erosion. It’s all post-glacial sands and clays there, even the wind and the rain erode it,” he says. The natural erosion of Britain’s coastlines has, of course, been occurring since prehistory. As Perry notes, the area around the coastal village of Dunwich, which was once a mile inland, has been steadily corroded by longshore drift over centuries, with houses, churches and even entire communities being lost to the sea since medieval times. “This has nothing to do with carbon dioxide in the atmosphere,” he concedes, “but what hasn’t always happened is the melting of the polar ice caps, the rising of the seas and the ‘weather weirding’, which today is accelerating erosion.”

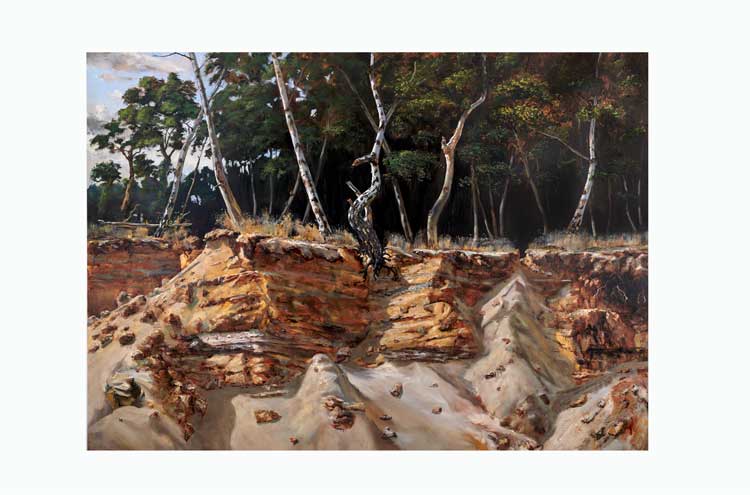

Julian Perry. Forest Edge, 2021. Oil on panel, 122 x 170 cm. Photo courtesy Colin Mills and Julian Perry.

The soft geology of the Suffolk coast, combined with extreme weather events and rising sea levels is having calamitous effects. “Most of that forest is now gone,” Perry says, gesturing towards his painting Forest Edge (2021), which depicts a section of precarious woodland on a clifftop, looking ready to slide into the sea at any moment. This “wall of entropy” is in Benacre, east Suffolk, a few miles south of Lowestoft, which, as Perry explains, “is one of the fastest eroding portions of coastline there is. It’s a beautiful spot. John Piper painted there, but it is losing about five metres a year, which is extraordinary.”

Perry has visited Benacre regularly in recent years, making small studies, which he then develops into larger paintings such as his Benacre Birch series. These enormous paintings of birch trees ripped from the ground and seemingly hovering in mid-air, were originally produced for a 2015 exhibition in that most vulnerable of maritime cities, Venice. Inspired by Albrecht Dürer’s small watercolour the Great Piece of Turf (1503), each painting features a silver birch wrenched from its clifftop moorings at Benacre, but with its roots still embedded in a clod of sandy soil. “I wanted to create this beautiful but intimidating experience of having these things towering above you, like they were on the cliff when I saw them,” Perry says. “I’ve treated them as still lifes by abstracting them, isolating them on neutral white backgrounds. The root balls are massively biodiverse and my pictures represent what is being lost to erosion.”

Julian Perry. Benacre Birch I, 2015. Oil on two panels, each 122 x 184 cm (Total 244 x 184 cm). Photo courtesy Colin Mills and Julian Perry.

This is the first time that Perry’s Benacre Birch paintings have been shown in the UK. As with Venice, the port city of Southampton is an apt venue for these pictures. Its location on the highly tidal River Itchen, which carries huge volumes of water from the Solent into the heart of the city twice a day, makes the area similarly vulnerable to fluctuations in sea level. The sea’s power to affect the landscape is alluded to by the exhibition’s title, There Rolls the Deep, which is taken from a line in Alfred Lord Tennyson’s 1850 poem In Memoriam, which, for Perry, “brilliantly expresses the mutability of landscape. As a landscape painter, you only have to paint somewhere and revisit it a little while later and it’s changed. In my case, it usually seems to have changed a heck of a lot.”

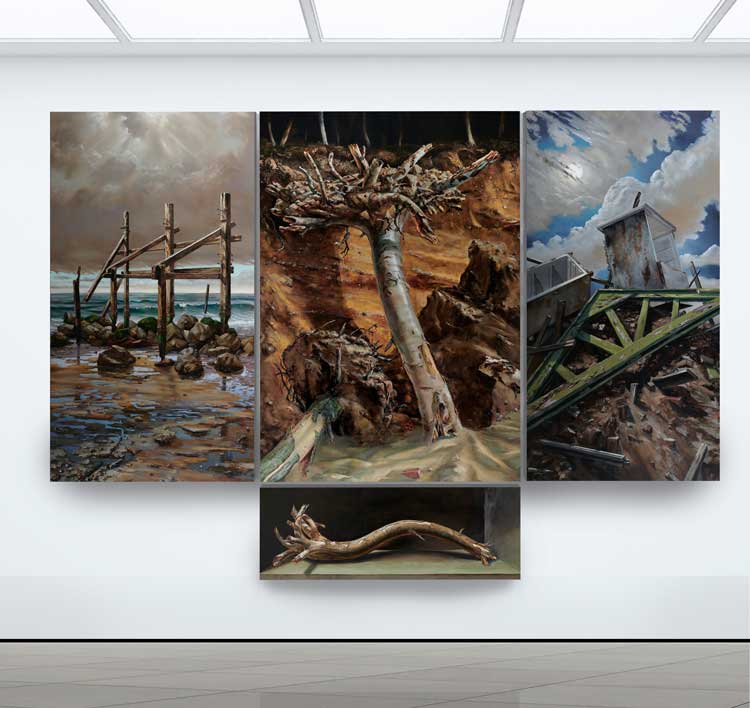

Julian Perry. Altarpiece to the Assumption of CO2, 2021. Oil on four panels, 244 x 302 cm. Photo courtesy Colin Mills and Julian Perry.

At the heart of the exhibition, in a sanctum-like space, is Perry’s Altarpiece to the Assumption of CO2 (2021), a four-panel work that draws parallels between the high drama of coastal erosion and art historical depictions of Christ’s crucifixion. The lighting here is low, and the walls are painted grey, while the ecclesiastical atmosphere is heightened by the songs of the 12th-century German Benedictine nun Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) played through speakers in the gallery. Perry explains that idea for the altarpiece grew out of a conversation with the curator, Dan Matthews. “I was pitching ideas for a show here and was being a little unambitious, suggesting that we could do a retrospective, maybe with some new paintings produced locally, but Dan wasn’t looking very impressed. Then I looked over his shoulder and spotted Allegretto Nuzi’s altarpiece [The Coronation of the Virgin, 1360] and found myself saying: ‘Well, I could do you a secular altarpiece to climate change’, and he said, ‘Wow, that sounds amazing’, though I didn’t have the faintest idea what that meant! Four years later, and after a lot of hard work, we’ve got one hanging here.”

Julian Perry. Clifftop with Fridge Freezers, 2009. Oil on panel, 20 x 30 cm. Photo courtesy Colin Mills and Julian Perry.

The altarpiece format has inspired some of western painting’s most emotionally charged images. For Perry, the greatest of these is Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, originally painted for the German Monastery of St Anthony in Issenheim and a major influence on his own altarpiece. “It’s one of my favourite paintings,” he enthuses. “I’ve known about it since I was about eight years old. It’s just a brilliant synthesis of hyper-realism and gothic drama. Like Graham Sutherland, and Picasso before him, I am in thrall to Christ’s nailed hands. The painting has a visceral realism to it, but also a slightly odd and mysterious quality.” Perry’s altarpiece was originally envisaged as a three-panel work, but the Covid-19 pandemic added a year to the project, allowing him to expand the piece with another, smaller image at its foot, known as a predella panel.

Julian Perry. Loss, centre panel, Altarpiece to the Assumption of CO2, 2021. Oil on panel, 170 x 122 cm. Photo courtesy Colin Mills and Julian Perry.

The central panel, titled Loss, depicts the cliffs at Benacre, where a sycamore tree hangs upside down after tumbling down the cliff. “The image echoes Christ on the Cross, the Corpus Christi of Christian iconography, but for me it is an image of the natural world inverted, a situation so crazy that trees are literally turned upside down and sacrificed to the rising sea,” Perry says. To the left of this is Hubris, an image of the remnants of wooden coastal defences on the beach at Happisburgh in Norfolk. “These revetments were built in the late 1950s, but they’re having a hard time of it,” he notes. “They worked for about 10 years very effectively, but in the end the sea got the better of them. They are broken monuments to the victory of the sea over carpentry. If you go to that particular location, the beach is like a battlefield with failed coastal erosion projects of all sorts of technologies and materials, all of which have proved to be ultimately useless in the face of rising sea levels and winter storms.”

Julian Perry. Hubris: and Muddy Footprints, left panel, Altarpiece to the Assumption of CO2, 2021. Oil on panel, 170 x 90 cm. Photo courtesy Colin Mills and Julian Perry.

The right-hand panel appears to show a junkyard but is, in fact, all that remains of an old dairy near Skipsea in East Yorkshire. “I found it sliding down the clay cliffs in 2008,” Perry recalls. “You can see fridge-freezers and the roofing trusses of the annihilated dairy. I call that image Vanity because it has a slight domestic quality to it and yet it’s ultimately doomed. There’s a full moon in the sky because that’s when the worst coastal erosion happens, when you get a spring tide.” Underneath these is the predella, titled Death, an effective piece of trompe l’oeil inspired by Hans Holbein the Younger’s Dead Christ (1521), though the recumbent figure is exchanged for an image of a dead tree that Perry found on the beach at Covehithe, a fast-eroding stretch of coastline north of Southwold.

Julian Perry. Vanity, right panel, Altarpiece to the Assumption of CO2, 2021. Oil on panel, 170 x 90 cm. Photo courtesy Colin Mills and Julian Perry.

The genuinely religious aspect of this presentation is the sublime choral works of Hildegard von Bingen, one of the first named composers in the history of western music. “This is the music that I’ve been listening to in my studio as I painted these pictures,” Perry explains. “I’m not a musicologist but it has a kind of modernism to it. There are atonal passages that could have been written in the early part of the last century, and it’s profoundly beautiful and sad – all the kinds of things that I’m going for in this space.” For most of her life Hildegard lived in a secluded hilltop monastery in the Rhineland, leaving behind a remarkable body of liturgical music as well as illuminated manuscripts and writings on theology, botany, biology, medicine and the arts. She remained virtually unknown until the 800th anniversary of her death in 1979, after which interest in her life and music has grown considerably. This is the first time that Perry has experimented with sound in an exhibition. “I wanted to evoke the experience that I was having in front of these paintings in the studio,” he says. “Also, Hildegard was a keen botanist and is the patron saint of the Green party in Germany.”

Flanking the altarpiece, and continuing the invocation of religious language, are 14 small diptychs, or Stations, encased in Perspex containers inspired by the perspective boxes of the National Gallery. Referring to the Stations of the Cross, these curious mirror boxes contain double-sided panel paintings that pair various images of the sea and the destruction it has wreaked; in each piece, one image faces outwards towards the viewer, while the other, painted on the reverse, is reflected in a mirror at the rear of the box.

Julian Perry. Concrete Sea Defences Happisburgh & Beach at Dulwich, 2018. Oil on panel, 20 x 20 x 11 cm. Photo courtesy Colin Mills and Julian Perry.

Some viewers may suspect that by referring to religious language in this way, Perry is assuming the role of a preacher, but for him it is all about appropriating the drama of Christ’s Passion. “The Christian faith is based on a cult of human sacrifice and that’s quite shocking if you’re not used to it,” he says. “My sister-in-law is Malaysian and when she arrived in this country she went into a Catholic church and was horrified to see an image of a young man nailed to a cross. It’s rather perverse and weird if you’re not brought up with it. Those are all sentiments that I wanted to imbue in my audience. But I’m not trying to make people feel guilty about climate change. As a devout atheist, I was attracted to appropriating all the sorrow, theatre and wretchedness of a crucifixion to express the tragedy of what is happening to the world’s climate and its dependent ecology.”

Although there is no physical altar in the gallery, Perry’s referencing of the altarpiece format naturally evokes thoughts of sacrifice, whether it is the sacrifices that nature has endured to enable our modern lifestyles or the sacrifices that are needed to reverse the damage. Perry concurs: “If this world is going to change, if this process is going to stop, we’re going to have to make some changes ourselves.” David Matless, writing in the exhibition catalogue, notes: “Perry’s ‘Assumption’ altarpiece invokes theological language, but in doing so also points to the ways in which something – CO2 – assumes inevitable narrative presence.” To ‘assume’ something is also to take it for granted. Perhaps this leaves the door open to those who question the current narratives surrounding climate change and CO2? “Obviously it’s a pun on Mary’s assumption into heaven, but the word assumption itself leads in various directions,” Perry replies. “Good titles precipitate discussion and I hope the work creates a debate, but I also hope that viewers are clever enough to realise that the word ‘assumption’ refers to CO2 being assumed, or taken up, into the atmosphere.”

Indeed, the presence of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere is referenced throughout the exhibition. Each wall label notes the level of the gas in the atmosphere when it was painted relative to today’s level. For instance, using data from the 2 Degrees Institute, the label accompanying Perry’s Forest Edge (2021) informs us that there was 1% less CO2 in the atmosphere than today, whereas in 1827, when JMW Turner’s engraving Dunwich was produced, there was 32% less of the greenhouse gas. In this, Perry highlights the alarming rise that has occurred since the 1800s.

Julian Perry: There Rolls the Deep. Installation view. Photo courtesy Southampton City Art Gallery and Julian Perry.

Another Turner hangs in the exhibition’s final room alongside several other paintings from Southampton City Art Gallery’s collection, selected by Perry for their influence and relevance to his own practice. Fishermen Upon a Lee-Shore in Squally Weather (1802) is a fine early composition. “I’m a big fan of it,” enthuses Perry. “These poor fishermen are trying to go out and fish on a crappy day with the wind against them. I see it as an image of a bad day in the office, and we all have days like that. It’s technically charming and is the sort of painting that I have spent a long time looking very closely at and trying to imitate.” Among the other works, which include Gustave Courbet’s richly coloured seascape La Vague (c1860) and William Nicholson’s strikingly stark Cliffs at Rottingdean (1910), is Goswijn van der Weyden’s remarkable 16th century triptych St Catherine and the Philosophers (1510). “It’s an exquisitely painted image of debate,” says Perry. “St Catherine is intellectually fighting for her life. She is defending her Christian faith against all these pagan philosophers. She is glorious, strong, beautiful, intellectual and a picture of calm in the midst of these relatively ugly individuals. She loses the debate, but the picture itself is intended to be didactic, which is pretty much what I’ve tried to do here in this exhibition.”

When Van der Weyden painted his triptych there was 32% less CO2 in the atmosphere than today. In the face of climate destruction, what hope does Perry have for the future? “What is needed to save the world is a change in consciousness. That’s all we can hope for,” he says. “I’m not one of these people who says I have faith in young people because that’s not fair on young people. They didn’t cause this mess, but they’re going to live it. It’s my generation who have to scream and shout and say this is not good enough,” he says. “Because I don’t believe that there is any god pulling the levers, it’s down to us to pull the levers and make the world better than it is at the moment. I am aware that it would be hypocritical of me to not be doing something, so I try to keep my carbon footprint low, but I’m not going to claim I’m doing particularly more than anyone else. The sharp end of my attempts to help the world is to create exhibitions like this in which discussion flows and attitudes change.”

• Julian Perry: There Rolls the Deep is at Southampton City Art Gallery, Southampton, until 4 June 2022.