John Abell. Photo: Jen Abell.

by CHRISTIANA SPENS

In his new paintings and prints on show in Through Great Waters, at the Arusha Gallery in Edinburgh, the Welsh artist John Abell creates an entrancing dreamworld, filled with spirits and ships, skeletons and swaying trees, horsemen and weeping women. He trained at Camberwell School of Art and self-trained in printmaking, and is influenced by German expressionism and Hinduism, but Abell considers himself first and foremost a Welsh folk artist, drawing on memories and impressions of his country to reveal a warm and mesmerising vision of a liminal, in-between world, where time stops and death is not to be feared, but part of the dance of life.

John Abell. Esgyn Ir Mamwrad, 2021. Oil on canvas, 152.5 x 122 cm. Image courtesy the artist and Arusha Gallery, Edinburgh.

His ghosts are happy, his horsemen of the apocalypse neither intimidating nor distressing; states of dissolution and creation coalesce peacefully in a meditation on consciousness, imagination, and how we live in many states and times at once. Drawing on Welsh mythologies, poetry and eastern philosophies, Abell reveals his art practice to be a part of his spiritual practice, and in so doing creating a blissful and revelatory world in which to explore and meditate.

He spoke to Studio International via Zoom at the start of his show at the Arusha Gallery about his most recent work and influences.

Christiana Spens: Some of your recent paintings recall figures and motifs from Welsh folklore. Can you tell us how you came to know these stories, and why you have interpreted them as you have?

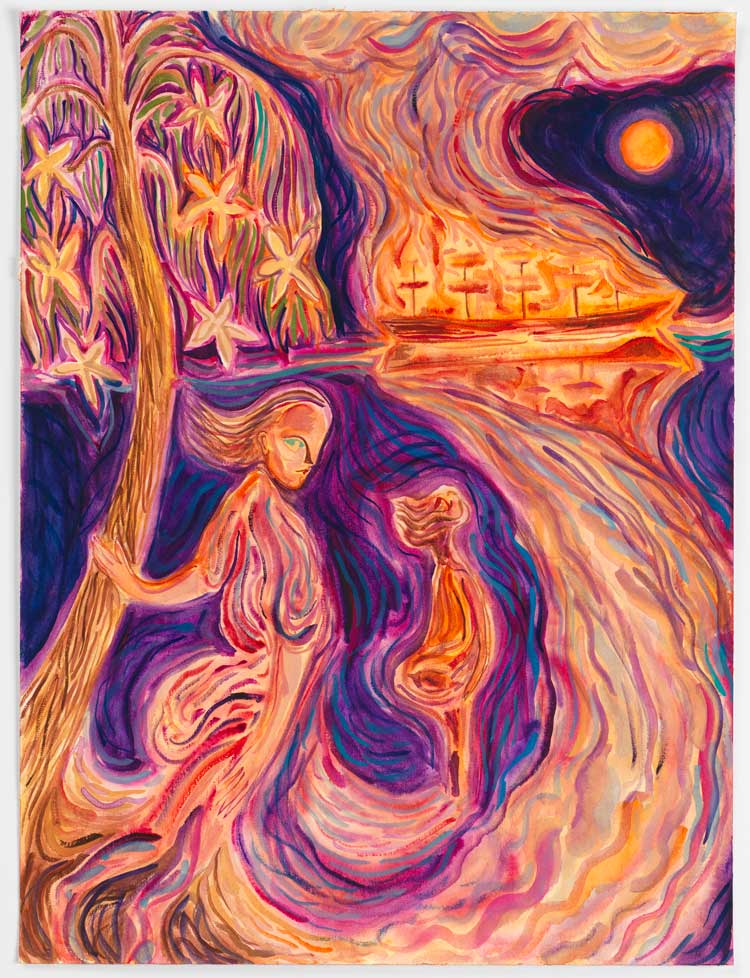

John Abell: The title of the show takes its name from a poem by RS Thomas, for my money the most interesting Welsh poet of the 20th century with that surname. There is a painting in the show called Esgyn Ir Mamwrad, which translates as “return to the motherland”, which deals with notions of hiraeth, a Welsh word that can’t be translated into English. It means a longing, or yearning, for home. These are the only overt references to Wales in the show, I’d say, aside from me being Welsh, and all the work being made in Wales. I think if you’re interested in Welsh history, you take in the folklore almost by osmosis, you grow up with these stories, Y Mabinogi, things like that.

,-2021.jpg)

John Abell. The Lighthouse (Hope Totem), 2021 Oil on canvas, 51 x 40.5 cm. Image courtesy the artist and Arusha Gallery, Edinburgh.

CS: Lighthouses, ships, mermaids and the sea appear regularly in your work. What is their significance, and what do you associate with them? When did you first start using these symbolic figures and features in your work?

JA: I used to sail tall ships and that had a big impact on me – imagery that would resurface from that time. One of my favourite places on Earth is Ynys Llanddwyn, off the coast of the bigger island, Ynys Môn (Anglesey), which has some incredible old lighthouses. Then there’s South Stack, another favourite. For me, lighthouses symbolise hope: they’re optimistic structures, built to stop ships foundering. Over the last year or so, it’s been important to me to put these hope totems out into the world. The sea I like because it’s bigger and more powerful than us, it’s an elemental force full of alien life if you’re a terrestrial being.

,-2021.jpg)

John Abell. Clifftop (Passing Ship in the Moonlight), 2021. Oil on canvas, 41 x 30.5 cm. Image courtesy the artist and Arusha Gallery, Edinburgh.

CS: Welsh prehistoric landscapes, seascapes, flora and fauna are also important in your work, and creating a world that is very much about Wales itself, as well as your own feelings about it as your home. Do you draw from observation of real places and things, or from memory and imagination?

JA: I’m not sure if my work is really place-specific, I think of it as pretty universal in what it is dealing with. It’s not literal, I am not drawing things from life in an objective way, trying to depict landscapes or places that are recognisable. If you’re familiar with the sea, or people, then I’d like to think you will have an idea of what might be going on in the work. All my imagery comes from my imagination, which is fuelled by memories I have and places I recall. I tend to think most things I depict are interpretations of things I’ve seen or done.

,-2021.jpg)

John Abell. Magenta Willow (Another Possible World), 2021. Oil on canvas, 91.5 x 61 cm. Image courtesy the artist and Arusha Gallery, Edinburgh.

CS: By drawing on this folklore and legend, you inevitably touch on ideas about Welsh history and identity, and yet you resist typical nationalist narratives, while opening up imaginative legacies and routes to feeling part of a place. Can you tell us a little more about what “home” and identity mean to you, and how you explore these ideas in your work?

JA: I guess you could say I’m a nationalist, or at least a British nationalist would say I am, because, of course, I believe Wales should be an independent country and not ruled by a totally corrupt English-serving institution like Westminster. Welsh history is interesting because it’s one of protocolonisation. It’s England’s first colony, will probably be its last, and it’s a history of somewhere stubbornly refusing to give up its language and uniqueness in the face of centuries of attempts to homogenise it into some notion of Britishness. Britishness, of course, means Englishness. It’s also a history of class consciousness, which we could do with now more than ever. And it’s a history that doesn't get taught to people in Wales.

I don’t really think much about identity. It doesn’t particularly interest me much to think about myself unless it is in relation to how I interact with the world around me and whether I’m making a positive contribution to those around me.

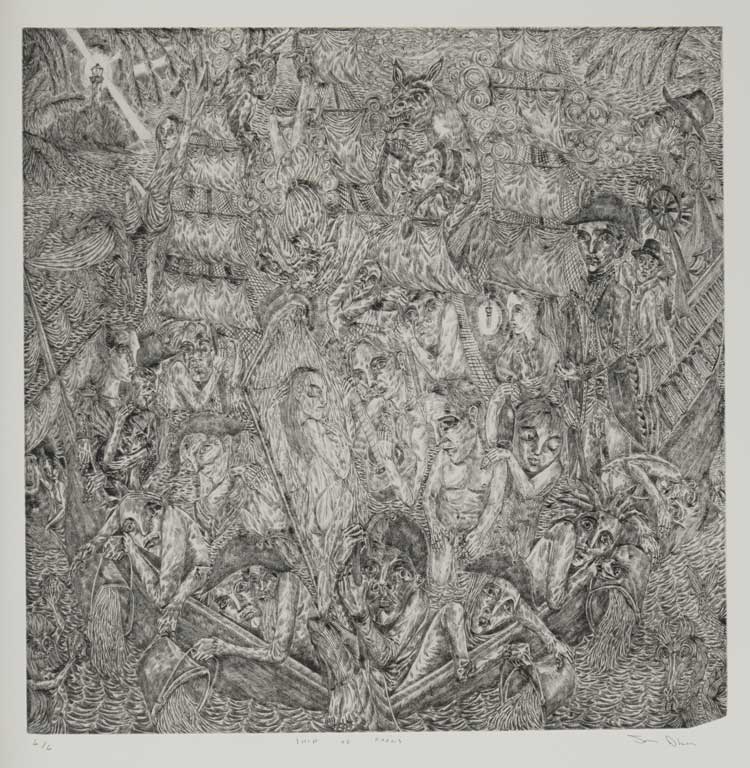

John Abell. Ship of Fools, 2021. Etching, 49 x 49 cm. Image courtesy the artist and Arusha Gallery, Edinburgh.

CS: You have trained in printmaking (especially linocuts and etching) for many years; how has that practice influenced the way you draw and paint? What is it about printmaking that you find important in your development as an artist, and in the exploration of folklore, history and philosophy?

JA: I’m a self-taught printmaker, which I think has helped my woodcuts and linocuts be pretty ambitious. I didn’t have anyone telling me that certain things would or wouldn’t work out.

For me, it’s all the same thing, it’s just my work, and one aspect of my work informs another. A motif or idea will start in an engraving or linocut, say, and I’ll probably get round to painting it at some point. And each medium offers different possibilities, things that work in linocut won’t necessarily work out in a painting, even if the motif is the same.

An interest in printmaking facilitated an interest in print culture, the mass dissemination of images with woodcuts that was prevalent until the 18th century in Europe. Incredible illustrations that were always super crude and to the point, depicting all sorts of fantastic things, such as witches’ sabbaths, odd creatures and current affairs, some even depicted the fashions of people from different towns! That type of thing fascinates me, homo sapiens has always been the same animal with the same interests and morbid curiosities.

John Abell. A Fire on the Water, 2021. Watercolour on paper, 56 x 42.5 cm. Image courtesy the artist and Arusha Gallery, Edinburgh.

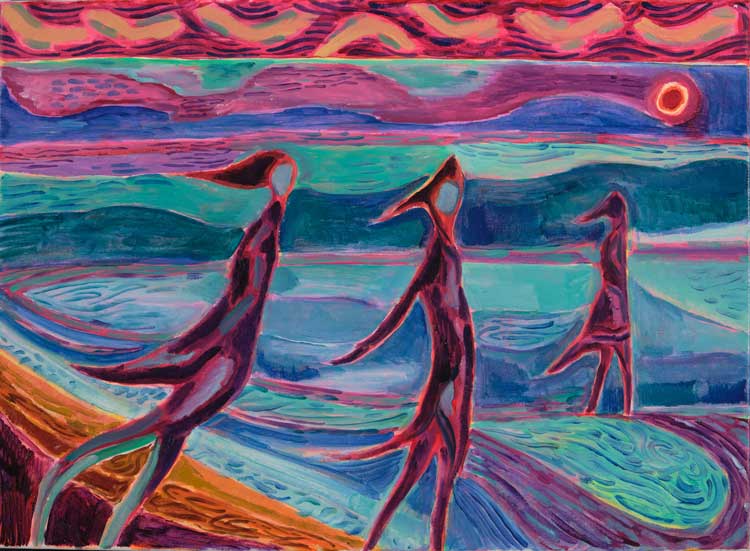

CS: Your recent work, with its skeletons and spiritual undertones, seems to confront death and loss, revealing it to be a non-threatening part of life, rather than a horrifying spectre. Given that you worked on these paintings in the past year or so, how did the current situation inform your work?

JA: My spiritual condition is very important to me, it’s something I am very aware of particularly if I’m not maintaining it as well as I should be. Working is like repeating a mantra, do it again and again and mean it. Repetition is important.

The work I made over this last year has been fairly hopeful, I think. Maybe with some of the apocalyptic poetry set to the linocuts, they have something of surrendering about them, surrendering to the situation the human race insists on building for itself. It is very frustrating to be a sentient being and watching the way the world works at times.

One thing that happens to all living things is death, and that’s fine, it’s just the way it works. I’m not a transhumanist by any stretch of the imagination.

John Abell. On Some Faraway Beach, 2021. Oil on canvas, 40.5 x 56 cm. Image courtesy the artist and Arusha Gallery, Edinburgh.

CS: Seeing these imaginative, hallucinogenic and quite spiritual paintings and prints, I begin to consider these alternative realities and even distorted realities as a way of living and seeing the world, in a way that is comforting and revelatory. Do you consider the expansion of vision and possibility as a key part of your role as an artist, or is it more intuitive, direct and personal a response? Or both?

JA: It’s both, I guess. I work very intuitively but often on a number of similar works at the same time, so I can explore different possibilities with an image, kind of trying to have my cake and eat it.

I do see my work as a type of devotional art, and a lot of the art that really resonates with me is devotional art. It’s totally unironic and sincere, which are qualities I admire in anyone and anything. I would like someone seeing my work to remember it. Aside from that, I have no control over what they feel or think when they see it or spend time with it, and I’m very happy about that.

CS: I have read that poetry (and particular poems by TS Eliot and Czesław Miłosz) have inspired your work. Can you tell me a little more about how it resonated for you? Do you write poetry yourself?

JA: I remember reading A Song on the End of the World by Milosz about a decade ago and it stuck with me, with the world how it was last summer, I reread it and immediately made a linocut of it. I had to edit it extensively while still, I hope, getting it across. From there, it felt natural to explore other poems about ending, and almost by accident it became a project. I'll probably continue it.

I write often, some comics, I’m halfway through a woodcut novel I’m making, and I also write down thoughts and ideas. I write down my dreams, a lot if images come to me in dreams. The text in my prints is often my own.

CS: These paintings often remind me of the lovers in the corner of Pieter Bruegel’s The Triumph of Death, in that they are romantic but also realistic and even fatalistic in their visions of love and serenity amid death and chaos.

JA: Thank you, that’s a comparison I think any artist would welcome. Yes, I guess the figures are in the situations they are in, and they've got to let it wash over them.

• John Abell: Through Great Waters is at the Arusha Gallery, Edinburgh, until 19 December 2021.