Arusha Gallery, Edinburgh

12 June – 12 July 2020 (currently online; reopening on 29 June 2020)

by CHRISTIANA SPENS

When the statues of prominent colonialists are being toppled or removed amid global Black Lives Matter protests, it is prescient that in Ilona Szalay’s latest exhibition at the Arusha Gallery we are confronted with different sorts of statues, as well as figures, and an inescapable atmosphere of tension, melancholy and strife.

Ilona Szalay. Captive, 2020. Oil on aluminium, 100 x 75 cm. © the artist.

In Captive (2020), Szalay presents a female nude on a podium, turning to her left as a flame erupts – beautifully and dangerously – in the near distance. Her hand is seemingly tied behind her back so that her movement is restricted. In Winged Sphinx (2020), another female figure is transformed into a statue—again, the background red and burnt orange, flame-like. These two compelling paintings (both oil on aluminium and works in progress) are timely and urgent in their implicit reflection on current affairs. They show history as “real” and also broken, time as an illusion, a cloak shed in protest and defiance.

Ilona Szalay. Winged Sphinx, 2020. Oil on aluminium, 75 x 100 cm. © the artist.

Szalay, who was born in Beirut in 1975, read English literature at Oxford before doing an MFA at Central Saint Martins. The influence of narrative in her work is clear: there is an implied sense of happening, sensuality and effect behind every painting, seeming especially ethereal for being painted on transparent or opaque surfaces. There is also silent conversation, conducted in gestures, glances and mood – at times heavy, pregnant with worry and confusion. These figures are silent and yet their stories, their confusions, are impossible to ignore.

Ilona Szalay. Snakebite, 2019. Oil on aluminium, 200 x 150 cm. © the artist.

Szalay’s painted statues are scared, too; they are not memorials to men whose lives have now come under the stark judgment of modern perspectives, but modern figures trapped in stone, in the legacies of the past, in a physical situation that renders them vulnerable and exposed. Is this a sense of guilt, perhaps? A sense of existing and partaking in political and cultural discourses that can seem impossible, interminable? Are these figures trapped in shame, for being part of something that is a collective wrong? Their vulnerability is clear, their humanity fictional and in a way disturbing; they reflect the strange associations we embed in physical objects, the surrealism of symbolism, the ultimate incongruence and mortality of relics from our collective past.

Ilona Szalay. As Above So Below, 2020. Oil on aluminium, 200 x 150 cm. © the artist.

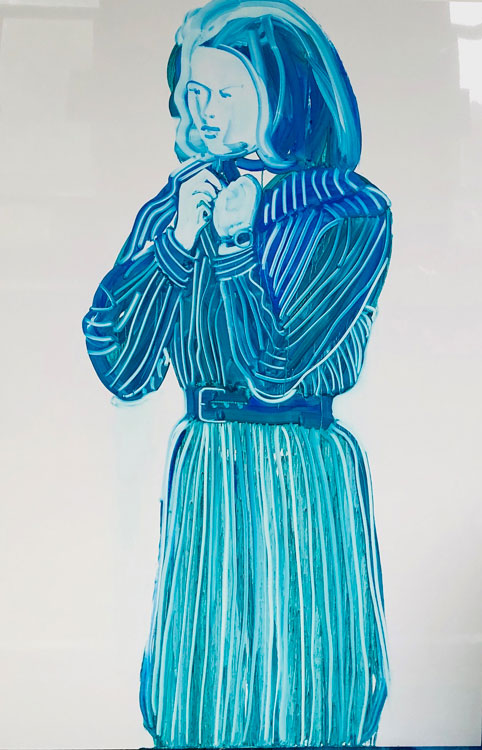

Female figures appear withdrawn and preoccupied, even frozen in their positions and roles. In As Above, So Below (2020), a mermaid-like figure floats above a kissing couple, the “sea” an inky black. She is trapped in her own mythology. In Striped Dress (2019), a woman painted in blue fixes her collar, seemingly in thought, her eyes fixed on something out of frame.

Ilona Szalay. Striped Dress, 2019. Oil on aluminium, 150 x 100 cm. © the artist.

Ilona Szalay. Some are Born to Sweet Delight, 2019. Oil on aluminium, 200 x 150 cm. © the artist.

In Some Are Born to Sweet Delight (2019), a half-naked figure rests awkwardly on a luxurious crimson bed, against a pink background. Though there is no other figure there, disembodied arms rest against her back; there is an implied restraint, or submission. Her expression is fearful and yet resigned.

Ilona Szalay. Trophies, 2020. Pen on paper, 25 x 30 cm. © the artist.

In Trophies (2020), this pose and expression is more crudely shown—again, the tension and fearfulness is palpable. The women exist in situations in which they are dominated and controlled; the frames are cages. They are like statues, too, memorialising power structures we are still unsure about, not knowing whether or not we can fully let go of them.

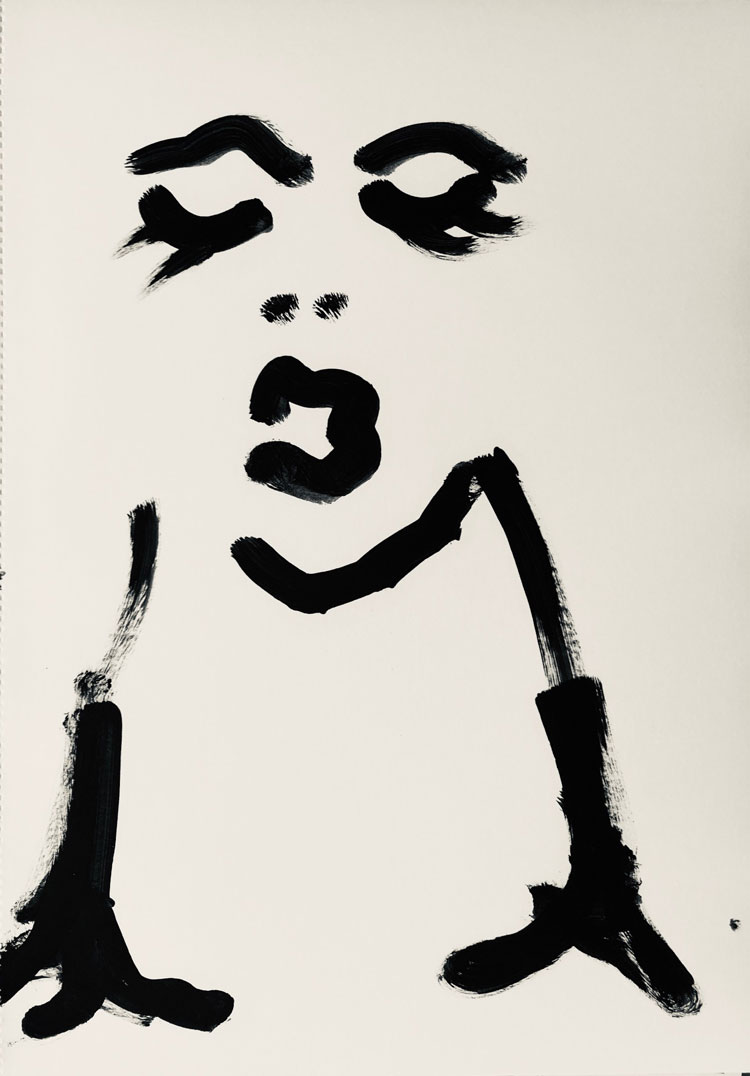

Ilona Szalay. Monochrome Series 8, 2019. Oil on paper, 42 x 30 cm. © the artist.

More assertive figures – drawn hastily in black oil paint on paper – give a sense of protest and resistance. In Monochrome Series 5 (2019), a speech bubble reads “Do what you want”, an ambiguous and compelling fusion of defiance and submission. In others in the Monochrome series, simple, looping lines express moods of outrage, exhaustion, shock, resignation and general chaos – ambiguously coexisting in these contested spaces. These contrasting feelings and expressions create a dialectic with the viewer, drawing one in and inviting a reflection on reaction, gesture and the ephemerality and connectedness of one’s own voice in moments of mass change. Power and vulnerability, involvement and detachment, dominance and submission all come together in a swirling, sensual vision of what it is to be a figure in a crowd, an individual affected by others.

Ilona Szalay. Monochrome Series 17, 2019. Oil on paper, 42 x 30 cm. © the artist.

As the artist said of her work recently: “To speak of injustice and inequity at the moment is akin to stating that the world is round or the sky blue, by which I mean that the truth of inequality of all kinds has rarely been so self-evident, at least in my lifetime. Be it race, gender or economic, these inequalities and fundamental injustices have always surrounded us but recently (and presently) it is as if a beam of searing light has illuminated them in all their brutal depth and breadth.” The artist, in her sensual and yet direct images of human fragility and complex interactions and dynamics, lets that searing light inform her own visions and understanding of human nature.

Szalay takes inspiration from William Blake, here, and especially the poem To See a World … in the Auguries of Innocence, which presents the idea that in our world, the micro and macro are always linked. Nothing is truly insignificant; everything is connected, relevant and meaningful. As Blake writes: “A robin redbreast in a cage / Puts all heaven in a rage.” In her recent work, Szalay illuminates the little things – the single, opaque figures, the broken statues, the singular gasps and sighs – and she shows that they are all meaningful, all part of a greater whole. Some Are Born to Sweet Delight, Some Are Born to Endless Night is a quiet reflection on current affairs and one’s own place in massive, global change. It reveals our smallness, but also our collective importance. Nothing is meaningless; each gesture, confused or otherwise, plays its part in the world’s march forward.