The Gee’s Bend Quiltmakers, installation view, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, 2 December 2020 – 6 February 2021.

Alison Jacques Gallery, London

2 December 2020 – 6 February 2021 (virtual exhibition walk-through)

by VERONICA SIMPSON

The slow and painstaking world of the handmade, high-quality artefact – each stitch, each brushstroke, each slice of the chisel lovingly and skilfully executed – came sharply into focus during 2020. That appreciation of what is well conceived and formed and under our noses has provided, for many, much-needed compensation for the shrinking of our daily worlds and encounters, heightened by the fear of real scarcity and uncertainty that still clouds our post-Covid prospects. Against this backdrop, beauty conjured out of genuine poverty and dire necessity takes on a new significance. So, it was with some excitement that I read about the arrival in London of the Gee’s Bend quilts, at Alison Jacques Gallery, in a show organised in partnership with the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, a non-profit organisation dedicated to the celebration of African American art and artists from the southern US states.

Leola Pettway and Qunnie Pettway working at the Freedom Quilting Bee. Courtesy Souls Grown Deep Foundation and Alison Jacques Gallery, London.

Gee’s Bend is a remote Alabama community of a few hundred inhabitants, many of whom are descended from freed slaves from the Pettway plantation. Since the mid-19th century, the Gee’s Bend women refined and evolved their quilting abilities in isolation and with extremely limited resources, to conjure their own compositional language. They have not crafted in obscurity, however: during the civil rights movement, they established a Freedom Quilting Bee collaborative. Their quilts, celebrated for their improvisatory and abstract qualities, are now regarded as a crucial chapter in the history of American art. They have also become highly collectible, acquired by prominent museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Gee’s Bend quilts were first honoured with a solo show at a major art institution in 2002, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, then in 2006 at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, and in 2018 at the Metropolitan Museum, New York, in History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

Loretta Pettway Bennett. Work-clothes strips, 2003. Denim, 200.7 x 152.4 cm (79 x 60 in). Courtesy Souls Grown Deep Foundation and Alison Jacques Gallery, London. © Loretta Pettway Bennett / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London.

While quilting has never enjoyed the profile in the UK that it does in the US, a few examples from Gee’s Bend appeared in 2020 at the Turner Contemporary, Margate’s We Will Walk – Art and Resistance in the American South South, showcasing artists and makers from Alabama and the surrounding states.

The focus here, though, with the 13 quilts on show, is the continuity and relationship that is tangible between the 12 makers, their works spanning nearly 90 years, from 1930 to 2019. Entering the first of the two white-walled rooms of Alison Jacques gallery, off London’s Oxford Street, the overriding impression is of characters in conversation with each other. There is a gentle call-and-response choreography about these large, soft, densely worked oblongs of fabric facing into the room, lining each wall, interacting with the double-sided works hung freely in the centre or – in the case of Annie E Pettway’s Housetop (nine-block variation, 1930) - laid flat, on a low, horizontal plinth.

The Gee’s Bend Quiltmakers, installation view, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, 2 December 2020 – 6 February 2021.

We do not need to be reminded that an absence of colour once typified the wardrobes and homes of the poor and disenfranchised all over the world; for centuries, colour and elaborate pattern were for the wealthy and well-born elite only; their use was even strictly prescribed according to social hierarchies. Nevertheless, Housetop makes much of the joyful geometries achieved through simple arrangements of sage, grey, cream and beige strips of fabric.

America Irby. Center Medallion, c1940. Corduroy, 210.8 x 193 cm (83 x 76 in). Courtesy Souls Grown Deep Foundation and Alison Jacques Gallery, London. © America Irby / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London.

Nearby, America Irby’s Center Medallion (1940) has judiciously dispersed four treasured strips of green around the inner borders, and embedded two more within a cluster of reds and blues concentrated in the centre of this otherwise largely cream, beige and grey arrangement. These flashes of emerald are vivid and life-affirming, in contrast to their bleached surroundings. I am reminded of a key motif in Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Beloved: the character of freed slave Baby Suggs – mother-in-law of the traumatised Sethe, who attempts to slay her own children rather than give them up to the brutal master she thought she had escaped - who retreats from the world, surrendering her senses to the appreciation of colour. “Took her a long time to finish with blue, then yellow, then green,” writes Morrison. A quilt with orange patches makes frequent appearances: “Two orange squares in a quilt that made the absence shout … In that sober field, two patches of orange looked wild - like life in the raw.”

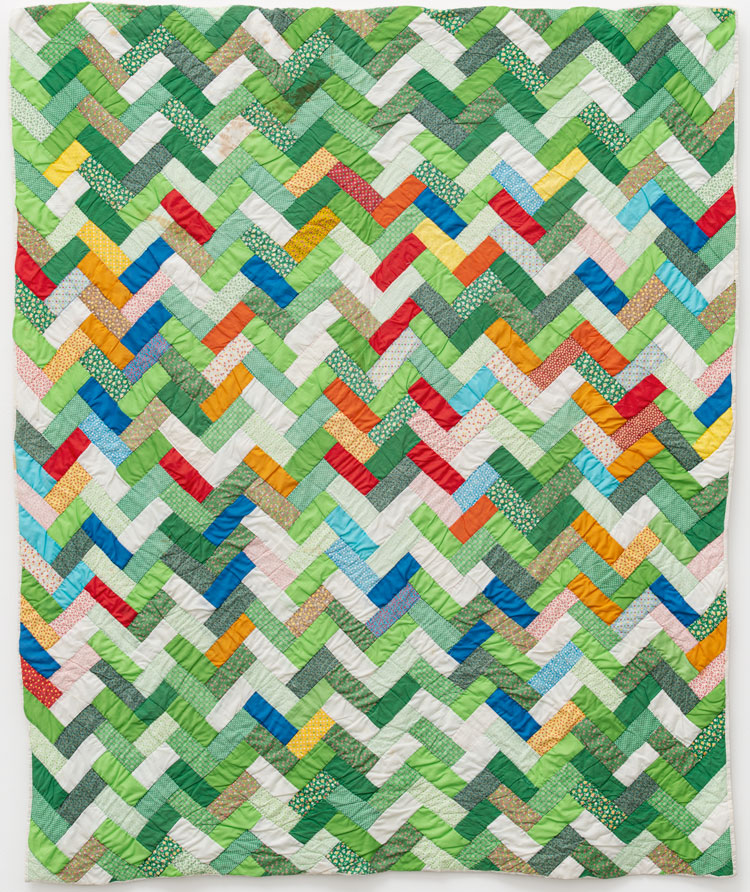

Candis Mosely Pettway. Coat of Many Colors (quilting bee name), 1970. Cotton and cotton/polyester blend, 200.7 x 170.2 cm (79 x 67 in). Courtesy Souls Grown Deep Foundation and Alison Jacques Gallery, London. © Candis Pettway.

In total contrast, my eye is then caught by a riot of green in the room beyond, from the next generation of quilters. This 1970 work, by Candis Mosely Pettway, is called, aptly, Coat of Many Colours: a zesty, repetitive pattern of triangulated green patches generously dispersed across the entire quilt, its mid-section animated by flashes of orange, yellow, red, white and blue. The confidence and skill in her placement of tones across this irregular, asymmetric arrangement calls to mind the masterfulpointillism experiments of Georges Seurat or of his admirer, Bridget Riley. Like a picnic viewed through thick summer leaves, this quilt would gladden the heart in any season, in any room.

Ethel Young. 'Crosscut Saw' - (quiltmaker's name) - five diamond-pieced rows with bars, c1970. Cotton, 182.9 x 177.8 cm (72 x 70 in). Courtesy Souls Grown Deep Foundation and Alison Jacques Gallery, London. © Ethel Young.

The evident skill in deploying asymmetric elements that typifies these Gee’s Bend makers has been attributed to the expressionistic exuberance of African art and textiles. But it may just as well have come from having an artist’s eye in really looking: in relishing the forms, shadows, patterns and hues of everyday life, from the nature abundant all around them to the tools they used in working the land – as indicated by Ethel Young’s 1970 work, Crosscut Saw. Here, she arranges five vertical columns of zigzagging, orange diamonds, offsetting the dominant column on the right (arranged against a grey background) with three orange on yellow columns in the mid-section and a teasingly irregular variegated background to the final one on the left.

Rita Mae Pettway. 'Pig in the pen' - block style, 2019. Cotton / polyester blend, 210.8 x 210.8 cm (83 x 83 in). Courtesy the Artist and Alison Jacques Gallery, London. © Rita Mae Pettway / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London.

As we move through the generations towards the present-day quilt-makers, the colours and textures become richer, deeper, more varied, in what is presumably a natural response to better times and greater resources. But there is still a wonderful confidence in the way Rita Mae Pettway, in Pig in the Pen – block style (2019), explores such unlikely hues in its concentric squares: it is Riley-esque in its boldness.

Loretta Pettway. Two-sided work-clothes quilt: Bars and blocks, c1960. Cotton, denim, twill, corduroy, wool blend, 210.8 x 180.3 cm (83 x 71 in). Courtesy Souls Grown Deep Foundation and Alison Jacques Gallery, London. © Loretta Pettway / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London.

Personally, I find the earlier quilts – from the 30s to the 70s - far more rewarding: the skill and talent made more apparent in their deployment of limited resources. Essie Bendolph Pettway’s two-sided quilt Blacks and One Patch (1973) is positively painterly in its opposing concentrations of ethereal pale elements to balance out the darker cluster. But my favourite is Loretta Pettway’s Two-Sided Work-Clothes Quilt: Bars and Blocks, of 1960. The fragility and evident wear in the fabric speaks of long years of use, its warmth a precious resource on cold nights for two or three generations. But more than that, I appreciate the way the uneven contours of the thick, interlocking grey and black strips that line its top section suddenly transform it into a landscape: dusky sky, black mountain, the blues and greens of a lake capturing the last light of the day. For an artwork to be able to transport you from the close confines of a room or cabin to the beauties of the great, wide world beyond is priceless; something we all now appreciate better than perhaps at any point in the last 50 years.

Alison Jacques Gallery, London

2 December 2020 – 6 February 2021