Gaudi, installation view, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, 2022. Photo: © Sophie Crépy.

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

12 April – 17 July 2022

by ANA BEATRIZ DUARTE

Whether or not you like Anton Gaudí, you will almost certainly like the exhibition devoted to his work at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. If you have been to Barcelona, you will recognise most of the city’s icons, but, here, you will also discover drawings and blueprints of unrealised buildings that show the creative process of the architect beyond the tourist trail. If you do not know Catalonia’s capital, this exhibition may make you wish to.

Although Gaudí’s work is very close to the French heritage, such as the art nouveau style, this is the first time his work has been exhibited in France since 1910, when some of his projects were part of a salon at the Grand Palais. Now, more than 200 pieces are on show at the exhibition at the d’Orsay museum, which follows the premiere in Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

Gaudí was not only an architect but also a furniture designer, sculptor, inventor and a master of the decorative arts. He was also a member of the flourishing bourgeoisie in Barcelona, a conservative religious man, and a fierce defender of the use of the Catalan language, and was once arrested for refusing to speak Spanish. The exhibition walks the visitor through these various facets of the world-famous, yet in some ways little-known, character whose work is part of Barcelona’s identity.

Antoni Gaudi. Francesc Vidal i Jevellí (cabinetmaker). Dressing table for the Güell Palace, 1886-1889. Wood, brass and mirror, 182.5 × 113 × 73 cm. Collection Güell de Sentmenat. Photo © MNAC, Barcelona, 2022.

Gaudí thought not only about structure but also about every little detail of the experience of inhabiting a building, from space to decoration and symbolism. At Orsay, for example, one discovers that even a sewage plate at Finca Güell was decorated by the architect. The general curator, Juan José Lahuerta, with Isabelle Morin Loutrel and Élise Dubreuil (in charge at Musée d’Orsay) have tried to reproduce a glimpse of this experience. At the entrance, the visitor is confronted with a reconstruction of the vestibule from Casa Milà, with some of its wooden doors in curved organic cuts. Other pieces of furniture are displayed in the following rooms, including armchairs, a dressing table, a clock and mirrors.

Clock for Casa Mila, 1905-1910. Workshop Esteva Figueras y Ses de Hoyos (manufacturer). Golden wood and brass, 103 × 50 × 20 cm. Collection Kiki et Pedro. Photo © Jacques Pepion / Sophie Crépy.

Another reconstruction awaits the visitor in the second room, this time in digital 3D format. It is the studio the architect built next to the construction site of the Sagrada Família when he refused any further commissions and decided to dedicate all his time to God, his “only client”, as he used to say. Documents, images and sculptures recovered from the site, which was destroyed in 1936, at the beginning of Spain’s civil war, were used to digitally restore the space where Gaudí spent the last years of his life.

Operator Arxiu Mas. Photograph of work for the decoration of the Sagrada Família, 1905, Barcelona. Institut Amatller d'Art Hispànic.

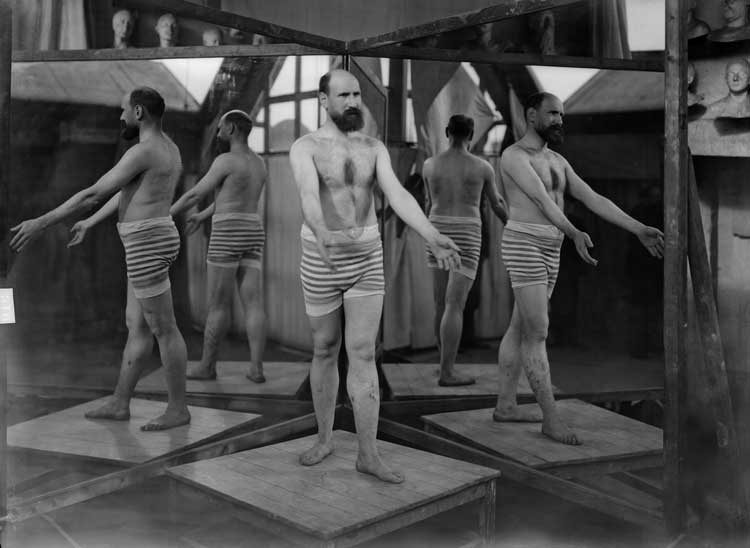

One can also see in vivo some of his studies for sculptures on the Sagrada Família’s facade, as well as the mirror system he created to enable him to see his models from every angle. In this way, he transformed the friends or other individuals, such as a baker and a beggar, who posed for him, into saints.

After these first “wow” moments, the exhibition follows a roughly chronological order, presenting impressive projects that Gaudí designed while at the Provisional School of Architecture in Barcelona, from which he graduated in 1878, when one of his teachers remarked that he was either a genius or a fool. Among them is a grandiose fountain for Plaza Catalunya, a central spot in Barcelona. If built, it would have been the tallest construction in the city at the time, a record now held by another of Gaudí’s projects, the 172.5 metre high Tower of Jesus Christ at the Sagrada Família.

Antoni Gaudi. Graduation project for a university amphitheater, cross-section, 22 October 1877. Graphite, watercolour and gouache, 65 × 90 cm. Barcelona, Cátedra Gaudí, ETSAB-UPC. Photo © Cátedra Gaudí, ETSAB, UPC / © CRBMC Centre de Restauració de Béns Mobles de Catalunya / Ramón Maroto.

After his work’s early stages, Gaudí, through the hands of architect Joan Martorell, started working for some of Barcelona’s wealthiest families. Photographs, press clippings, models and decorative elements of his luxury houses or palaces illustrate his work as well as his relationship with the regional elite’s representatives. The most famous among them is undoubtedly Eusebi Güell, who started a prosperous textile industry after his enrichment thanks to colonial trade. Güell became a close friend and Gaudí’s main patron. Now, more than 100 years after his death, his name is pronounced thousands of times a day by the hordes of tourists who visit the Palace and Park Güell. This was exactly what he expected when he commissioned the sites: to show bourgeoisie wealth and aristocratic power through the visible and enduring symbol of architecture.

Antoni Gaudi. Project for the Colonia Güell Church, c1908-1910.

Charcoal and white highlights on photograph, 59.5 × 46 cm. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Photo © MNAC, Barcelona, 2022.

Gaudí did not travel much, but his patrons did. They brought the artist many references, such as the arts and crafts movement in England, influenced by the French architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. It echoed Gaudí’s already solid devotion to this major exponent of art nouveau and neo-gothic that he knew from library books. Another strong influence on Gaudí was Islamic architecture, which he studied in the published work of the British architect Owen Jones.

Antoni Gaudi. Project for the Colonia Güell Church, c1908-1910.

Charcoal and white highlights on photograph, 61 x 47.5 cm. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya Photo © MNAC, Barcelona, 2022.

Other worldwide references, such as from Cambodia, Africa, Japan and the Philippines, were also sources of inspiration for him. Besides, his work refers to juxtaposed styles, such as baroque at Casa Calvet, Greek-style at Colonia and Park Güell, and Japanese at Casa Vicens (the first house Gaudí built). But he also created a style of his own, to which he added references from Catalonian history, nature and mythology, like the dragons at Park Güell and Casa Batlló.

Some of his houses, such as Calvet, Batlló and Milà (La Pedrera), are in the Eixample (Catalan for Extension) district, a neighbourhood designed during the late 1800s to host the new urban population settling in the city. It was at that time that Barcelona started to become what it is today – and Gaudí played a major part in it.

Gaudi, installation view, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, 2022. Photo: Ana Beatrice Duarte.

The exhibition at Orsay acknowledges this importance, but also tries to make up for the myths and cliches created around the architect. Besides highlighting his relationship with the rich and powerful, it also emphasises the origins of Gaudí’s creative process: not an innate, intuitive genius, but a professional obsessed with project, references and details, who took advantage of the changes of his time.

The Sagrada Família is where the controversy around Gaudí is greatest. It is the subject of three rooms at Orsay, as well as a documentary film by Marc Jampolsky broadcast by the French-German TV channel Arte, as one of the side events of the retrospective.

Antoni Gaudi. Maquette of the Nativity Facade with polychromy by Joseph Maria Jujol (projected in the exhibition), 1910. Original model, restored and polychromed, 330 x 162 x 53 cm. Barcelona, Fundació Junta Constructora del Temple Expiatori de la Sagrada Família

Photo: © Fundació Junta Constructora del Temple Expiatori de la Sagrada Família / Pep Daudé.

The extravagance of Gaudí’s plan is viewed with suspicion by many: 18 towers, three grand facades and countless sculptures to span the whole Bible, and an abundance of light to convey a place of deep spirituality. He wanted it to rival French medieval cathedrals. Indeed, it has at least one thing in common with them: the construction time. It started in 1883, and it is now expected to be finished in 2030. Gaudí led it for 42 years, from the age of 31 until his death in 1926, aged 73.

The complexity of the project and the missing drawings and models after the fire at the studio explain this length of time. Gaudí creates new techniques, derived and “improved” from the gothic style, as he said. He wanted to defy gravity, eliminating buttresses or flying buttresses, something he had already envisioned for the church at Colònia Güell, whose rare sketch illustrates the poster of the exhibition.

This grandiloquence was largely criticised by the leftists and anarchists of the time, who disagreed with the amount of money and time that was being invested in it. Pablo Picasso was one of them, as a caricature depicted in a video in the exhibition shows. Some of the rich were also upset by Gaudí’s creative process, including the Milà family, who complained about the duration and even the results of the artist’s project for their house.

This same extravagance, on the other hand, was the reason why the surrealists, years after Gaudí’s death, considered him a genius. In the very last piece of the exhibition, we see Salvador Dalí, also a Catalan, paying homage to his “master” at Parc Güell in 1954. The artist’s opinion contributed to revitalising and reinforcing the myth around the figure of the architect that the exhibition at Orsay now wants to counter.