Emily Jacir. Photo: John McRae.

by ANNA McNAY

Emily Jacir (1972, Bethlehem, Palestine) creates works of art across many mediums, exploring histories of colonisation, exchange, translation, transformation, resistance and movement. Books, libraries, etymology and the act of translation are also fundamental to many of her works, which are frequently diaristic in form, and impacted by direct experience, community interaction, and intense research.

Emily Jacir, Pietrapertosa, 2019-20. 179 cm diameter. Push the Limits - installation view at Fondazione Merz, Turin. Photo: Renato Ghiazza. Courtesy Fondazione Merz.

Currently showing a large stone medallion as part of the all-women group exhibition Push the Limits, at the Fondazione Merz in Turin, Italy, Jacir talks to Studio International by email about the origins and meanings of this work, as well as some of her other key projects.

Anna McNay: Aside from nationality, what do you consider to be the key themes of your work, and why have these themes particularly spoken to you?

Emily Jacir: Nationality has nothing at all to do with my work and is not a theme. My work investigates histories of colonisation, exchange, translation, transformation, resistance and movement.

AMc: Where do you feel to be “home” to you today?

EJ: My home is the Mediterranean, where I live and work, and where I feel at home.

AMc: You work across many different mediums – including installation, sculpture, film, photography and drawing. Do you have one particular medium that you consider your medium, or is it a matter of finding the medium that suits the message or subject matter of a given work?

EJ: Yes, I work across many mediums, from ceramics to painting to film to performance, and I don’t feel as if I have one that I consider specifically “my medium”. However, what does connect them are my subject matter and my concepts, which all these mediums embody, such as time, gathering, hospitality, public space, translation, excavating silenced historical narratives and many other things.

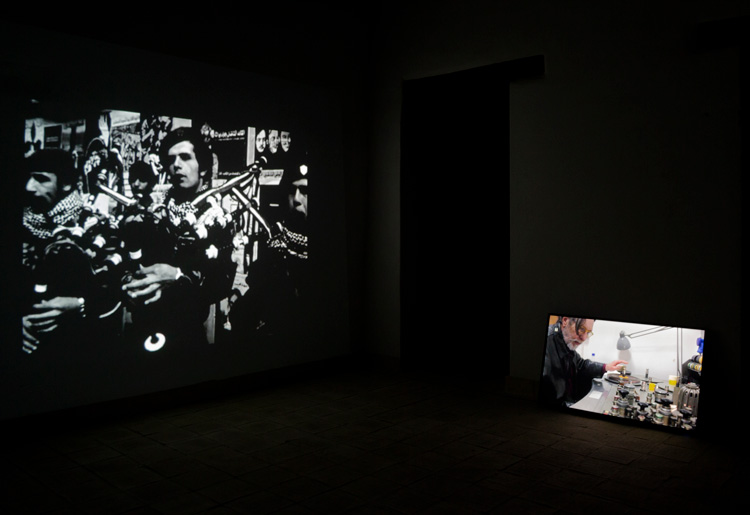

Emily Jacir, Tal al Zaatar (1977), 2014. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Iolanda Carollo.

AMc: Tell me a bit about how an Emily Jacir work comes into being. How is the seed of an idea sown? Where might you typically find your inspiration? How do you then proceed to research and collate material and ideas and build that into something complete?

EJ: My work is constantly coming into being. I am always working, moving, collecting things, scratching under the surface, researching very deeply into multiple subjects all at the same time. Walking is key to my practice. The materiality of things matters, too. I have so many ideas that it is hard to keep up with them all. My work can also be quite diaristic as well, and sometimes can be greatly impacted by direct experience. There are multiple ways in which my works come into being, from intense research, to direct experiences, to gathering and community exchanges, to movement, to the materials themselves, and what they represent and how they feel in my senses.

Emily Jacir. Ex Libris, 2010/2019. Paint on wall, Vicolo Valguanera, Palermo. Installation view, BAM Biennale Arcipelago Mediterraneo. Courtesy the artist, Fondazione Merz and Alberto Peola Gallery. Photo: Iolanda Carollo.

AMc: How different is, say, the process, perhaps in terms of ideas, for a piece of sculpture, which is typically one object, as opposed to an installation or film, where you can build in multiple elements?

EJ: I do not think the process is so different. My work usually begins with extensive research, and a work is born out of that research and undergoes many stages of transformation. Whether it manifests as an object, or a film or an installation, I still have to consider the same parameters from the work’s context, to its site-specificity, to the language I am using, to formal elements such as light and form.

AMc: You are currently exhibiting a circular, stone sculpture, Pietrapertosa (named after a small town perched on the Lucanian Dolomite mountain range, where you held a residency in 2019), as part of the all-women group exhibition, Push the Limits, at the Fondazione Merz in Turin. How did this come about?

EJ: In 2019, Pelin Tan invited me to participate in the Gardentopia project for Matera 2019. I was really excited to participate since so much of my work and research is focused on the Mezzogiorno [southern Italy]. The parameters of Gardentopia were for contemporary artists to produce something for the gardens of many small villages all throughout Basilicata. Pietrapertosa was assigned to me. I went there to research and to meet with the community in order to learn from them, to discuss their history with them, and to hear what they would like to see in their public garden. At the same time, Beatrice Merz and Claudia Gioia [the curators of Fondazione Merz] contacted me for Push the Limits, and I started thinking about that exhibition. I proposed this project to them, as I wanted to transport the object as an act – the transit of the object itself from Basilicata to Turin and then its return to Basilicata. This stone, this gorgoglione, which does not exist anywhere else, only in Basilicata, reflecting on the multiple histories of movement between north and south and the very different cultural spheres these places inhabit.

Emily Jacir, Pietrapertosa, 2019-20. 179 cm diameter. Produced by Fondazione Matera Basilicata 2019, Fondazione Merz in collaboration with Comune di Pietrapertosa. Assistants on the project Giuseppe Nora and Qais Assali.

AMc: The stone medallion is 179cm in diameter and 6cm thick and is engraved in both Italian and Arabic with the phrase: “You have come amongst our people and your life is safe.” What made you choose that specific phrase and how is it to be understood?

EJ: It came out of one of the most special moments I experienced while working on my project in Pietrapertosa. I was walking in the arabata quarter, conducting research into the town and its inhabitants when some elderly residents of the neighbourhood saw us and invited us to come inside their home for a coffee or tea – they said: “Ahlan wa sahlan.” They explained to me, with such great pride, the importance of hospitality to the people of the town, and that their tradition of hospitality comes from their Arab heritage. I asked them what “ahlan wa sahlan” means, and that’s how they translated it to me – that is literally their translation: “Sei venuto tra la nostra gente e la tua vita è sicura.” In that moment, I felt at home. That moment alone can explain what Pietrapertosa means and represents.

AMc: Tell me a little more about the Gardentopia residency itself. What did you learn about the Arab influence and the community’s culture?

EJ: As I mentioned earlier, I spend a lot of time in the Mezzogiorno and so these areas are very familiar to me. I started my research well before coming to Pietrapertosa and I already had a list of topics and themes I wanted to dig into and see, so I designed my residency based on my own interests. Before heading there, I looked into the local dialect and the words that are originally Arabic, I researched the history, and I had specific sites I wanted to see. I knew about the annual festival Sulle Tracce degli Arabi and how they celebrated their Arab heritage. Another key point is that, when I arrived, I wanted the locals to show me what was important for them, what they thought I should see, what they wanted to talk about. We looked at the earth, plants, what grows and when, the stone, what they felt lacked in the town that this project might possibly provide. The diverse languages and cultures that make up Italy are something to protect and also celebrate. The creation of a unified Italy has attempted to present a monolithic singular culture and flatten all this richness. Excavating these things has always been important to me. My piece, which had just gone up in the Merz show in Palermo, made sure to use the Sicilian dialect, for example, on my billboard.

AMc: After this exhibition, the sculpture will be permanently installed in the community garden in Pietrapertosa, created by the Gardentopia project. How does knowing a work will be on permanent display affect how you conceptualise it?

EJ: This work was produced specifically to be permanent in Pietrapertosa, and every decision I made in creating the work reflects that. It is a work for Pietrapertosa, so every element of it was chosen based on that, from the shape, to the size, to the design, to the words, to its placement. For example, on the day I arrived, a wedding had blocked the entrance to the town, and I had to get out of the car and stand aside and wait for them to pass. I looked up, and lo, there right above my head in the rock was an ancient rupestre, and it was a circle shape, which is why later, when I was designing my piece, I chose the circle – to connect to this and have a dialogue, as my garden is at the other side of the village.

AMc: Do you feel your works gain new readings and layers when exhibited alongside the works of other artists, as in Push the Limits, for example?

EJ: Absolutely, it’s an incredible constellation of works in Push the Limits, and each time you go through the show you can follow a different trajectory through the works.

Emily Jacir, Material for a film (detail), 2004–07. Multimedia installation, three sound pieces, one video, texts, photos, archival material. Photo: Emily Jacir. This work was devised in part with the support of La Biennale di Venezia. © Emily Jacir 2004.

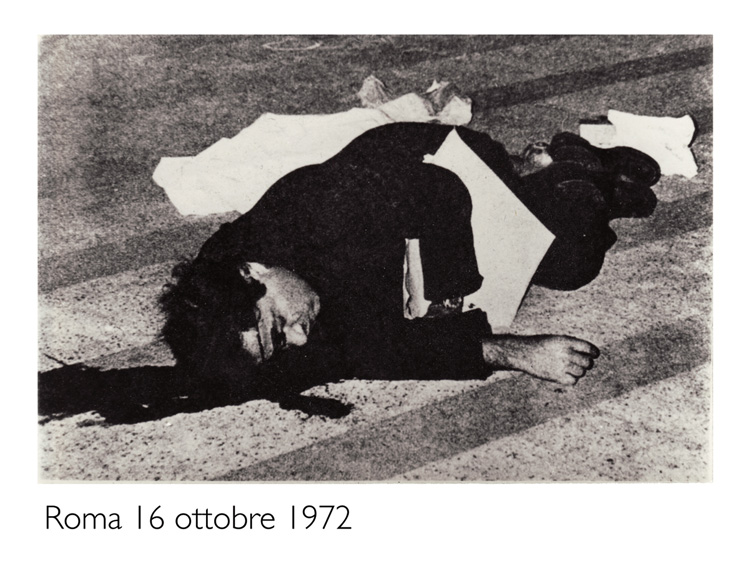

AMc: You won a Golden Lion at the 2007 Venice Biennale for Material for a Film (2004-), an immersive installation based on the life of the Palestinian writer Wael Zuaiter, who was assassinated near his home in Rome, by Mossad agents in 1972. Can you tell me a bit about this work and how much of yourself also found its way in? Again, there is the Palestine-Italy link …

EJ: Material for a Film was based on the life of Wael Zuaiter, the first Palestinian murdered on European soil by Mossad. My own photos and writings, and interviews I conducted, comprise the bulk of the project. I had been researching all the Palestinians who were killed in Europe and the Arab world for many years (beginning around 1996) before I made this work, such as the writer Ghassan Kanafani and the poet Kamal Nasser, as well as many others.

As a teenage girl living in Rome, I was haunted by Wael’s story. We were always aware of the Mossad killings, both in the Arab world and in Europe. The work was an attempt to present a film as an installation, or a documentary about Wael in an installation format, in which the viewer, rather than being passive as is normally the case with documentary films, becomes an active participant creating the narrative themselves by moving through the installation and stopping, standing, slowing down and speeding up in the time they choose.

Emily Jacir, Material for a film (detail), 2004–07. Multimedia installation, three sound pieces, one video, texts, photos, archival material. Photo: Emily Jacir. This work was devised in part with the support of La Biennale di Venezia. © Emily Jacir 2004.

In the book For a Palestinian: A Memorial to Wael Zuaiter, there is a chapter entitled Material for a Film, written by the Italian film-maker Elio Petri and screenwriter Ugo Pirro. That chapter was the point of departure for my project. It is my journey of finding Wael in the traces he left behind. The process of my research re-enacts that of Elio Petro and Ugo Pirro, and, ultimately, that of Wael himself. I consider it a kind of collaboration across time, starting with Wael, and then Ugo and Elio and Janet Venn-Brown [an Australian artist and Wael’s partner], and then me. It is very important to note that this piece is also very much about my daily life in the contemporary situation I was living in as a Palestinian. The perimeter of the installation contains my writings and notes on working on the project – my book, in a sense. Very personal. A key part of this project was to create an archive and to make and take photographs and make documents – many of which were not in existence beforehand. I also re-articulated existing unknown material in various formats. My project is as much about the construction of an archive of a life as it is a commentary on the materials available for inclusion within this archive.

Emily Jacir, stazione, 2008–09. Public intervention on Line 1 vaporetto stops, Venice, Italy. Commissioned for Palestine c/o Venice, collateral event of the 53rd International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Veneza. © Emily Jacir 2009.

AMc: Your public intervention, stazione (2008-09), planned for Palestine c/o Venice at the 2009 Biennale, which would have involved putting up Arabic translations of the vaporetto stops along route 1 on the Grand Canal, was cancelled by the Venetian authorities. What was the reason for this – as far as you could find out – and how did you respond? Would you still like to realise it were the opportunity to arise again?

EJ: Absolutely! It’s my dream to realise it, and I very much hope that one day that can occur. Shortly before the opening of the Biennale, the project was cancelled by city authorities without explanation, despite initial consent. Supposedly, the vaporetto company received pressure from an outside source to shut it down for political reasons. I created a brochure in Italian, Arabic and English of the No 1 route and distributed it throughout the city. It contained a location map of the project, as well as the vaporetto map, which I translated into Arabic, and a brief explanation of the background to the work. I created and distributed the brochures to circumvent the censorship and make people think the work was actually happening. I also imagined people finding the map in the future and thinking the project had happened. At the pavilion, they only permitted me to include a note near my brochure maps stating that the project had been cancelled without further explanations.

AMc: Which of your works do you feel is the most significant or most sums up what you want your practice to be understood as being about, and why?

EJ: I am happy to say that I cannot answer this question, and I do believe that, if I could, it would mean I am dead creatively – fixed in place – no longer growing, changing, transforming, moving.

AMc: What are you working on at the moment? How have you and your practice been affected by Covid-19?

EJ: On 27 February, I got stuck at Rome airport and was unable to return home to Bethlehem. I have been stuck in transit ever since and away from my beloved dogs, my friends, the art centre I am running, everything. It deeply impacted me as well because, here in Italy, we lived through one of the strictest and longest national lockdowns in the world. I was alone in a flat with one window for months on end. I used to see friends in other places, such as New York, talking about being in lockdown, yet spending the day in the park, or in Berlin partying, or in Palestine going to funerals and weddings or celebrating Easter. We could not imagine doing any of those things here. Everything I was planning was cancelled. However, I managed to really create some amazing gatherings on line. I am currently working on a couple of new film projects, a new diary and a walking project.

• Push the Limits is at Fondazione Merz, Turin, Italy, until 31 January 2021.