Drew Edwards: Now You Can See the Universe, installation view, Laurent Delaye Gallery, Ramsgate. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

Laurent Delaye Gallery, Ramsgate

23 September – 23 October 2022

by BRONAĊ FERRAN

On a Saturday evening in late September, spilling on to the pavement of Addington Street, a route to the sea in Ramsgate’s historic town centre, a crowd gathers for the private view of an exhibition of sculptures by the artist Drew Edwards. Comprising 20 works made from flint, some lodged on granite bases, made between 2017 and the present, the exhibition offers a rare opportunity to appreciate the spectrum of what Edwards is doing. He was invited by Delaye to have his first solo exhibition in this space (formerly part of an undertakers, sandwiched between a vinyl record store, a cafe and a now disused burial chapel), and the location is a perfect fit with the artist’s preoccupations. As you approach the double bay windows of the gallery, a tableau is visible inside, conveying an uncanny strangeness of stone-multiples: concave and convex features present within the stones curve in various directions. Much of what Edwards produces involves a reconfiguring of human faces – heads with gaps and gashes where eyes, ears or mouths might usually be, or sometimes with eyes of turquoise or lapis lazuli.

Laurent Delaye Gallery, exterior view, Drew Edwards: Now You Can See the Universe. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

Edwards trained as an actor, but now focuses on sculpting, with flint as his primary medium. As the exhibition reveals, he has achieved a distinctive (self-taught) technique that appears to reveal hidden affordances latent within the materials he is using. He recognises, as he has put it, that he is in a sense in dialogue with elements that have been in existence for more than four million years, seeking to give them a contemporary meaning through the acts of carving and sculpting. He has spoken of his interaction with flint in terms of control and letting go of his ego in the process: “If you push it one way and it doesn’t want to be that, then it will push back the other way, and then you end up fighting it. If you fight it, you are not going to win, or you can compromise, but a lot of the time it will just show me.”

Drew Edwards, Russian Soldier, 2022. Flint, 42 x 21.5 x 22 cm (16 9/16 x 8 7/16 x 8 11/16 in). Photo: Bronac Ferran.

With a studio based on a working farm close to his home in north London, Edwards finds source materials in diverse locations, from the edge of the Thames to a Norfolk quarry, then brings bits of stone back to see how they interact with natural phenomena, not least the early morning light at different seasons. “If you get a shadow that is thrown across a piece of stone, it will suddenly show you what it wants to be – and at that moment, quickly, I will have to make some markings, then pick the stone up, take it away and leave it to be cut. It [has] revealed itself to me at that particular time, with the sun on it and with the shadow that has been cast. It is as if it comes alive and just wants to be, I don’t know, released. Then I bring it back and I live with it for a bit.”

Drew Edwards, The Skull, 2017. Flint, 117 x 52 x 34 cm (46 1/16 x 20 1/2 x 13 3/8 in). Photo: Laurent Delaye.

One of the most compelling works in this exhibition is entitled The Skull (2017). It forms what Edwards has called his own “death and life cycle”. It sits on a granite structure, on which he has carved a snake. On closer looking, a cryptic face (which Edwards describes as his “death-mask”) is visible to the left and a hand divorced from limbs appear to be crawling across the head, along with a set of teeth in partial indentation to the right.

Drew Edwards, The Skull, 2017 (detail). Flint, 117 x 52 x 34 cm (46 1/16 x 20 1/2 x 13 3/8 in). Photo: Laurent Delaye.

The work lucidly conveys Edwards’ willingness to confront mortality in multiple dimensions. In this instance, he does so by fracturing the human anatomy, stringently questioning notions of figurative cohesion, shifting the concept of the temporal physical body back into the ground of primeval time.

.jpg)

Drew Edwards, Wheel of Life, 2019. Flint, 44 x 44 x 18 cm (17 5/16 x 17 5/16 x 7 1/16 in). Photo: Bronac Ferran.

Aspects of circularity, the cyclical and non-linearity are heavily to the fore in other parts of the display, including the remarkable Wheel of Life (2019) and Womb (2022), a highly polished rounded surface sitting semi-precariously between a part-fragmented top stone and a narrower structure below.

.jpg)

Drew Edwards, Womb, 2022. Flint, 64 x 27 x 24 cm (25 3/16 x 10 5/8 x 9 7/16 in). Photo: Bronac Ferran.

This, as well as Bust (2021), reify aspects of the female body, while being dynamically counterpointed by a series of works that appear to challenge issues of power and masculinity with titles such as Emperor (2017), Libertin (2018) and Small Putin (2022).

Drew Edwards, Libertin, 2018, Flint, 117 x 37 x 42 cm (46 1/16 x 14 9/16 x 16 9/16 in) and Wheel of Life, 2019, Flint, 44 x 44 x 18 cm (17 5/16 x 17 5/16 x 7 1/16 in). Photo: Bronac Ferran.

Among various other “heads” included within this exhibition, several seem to speak to a masculine vulnerability: as if under the distancing of the (stone) face masks (subliminally recalling collective pandemic trauma) might run rivers of emotional undercurrent.

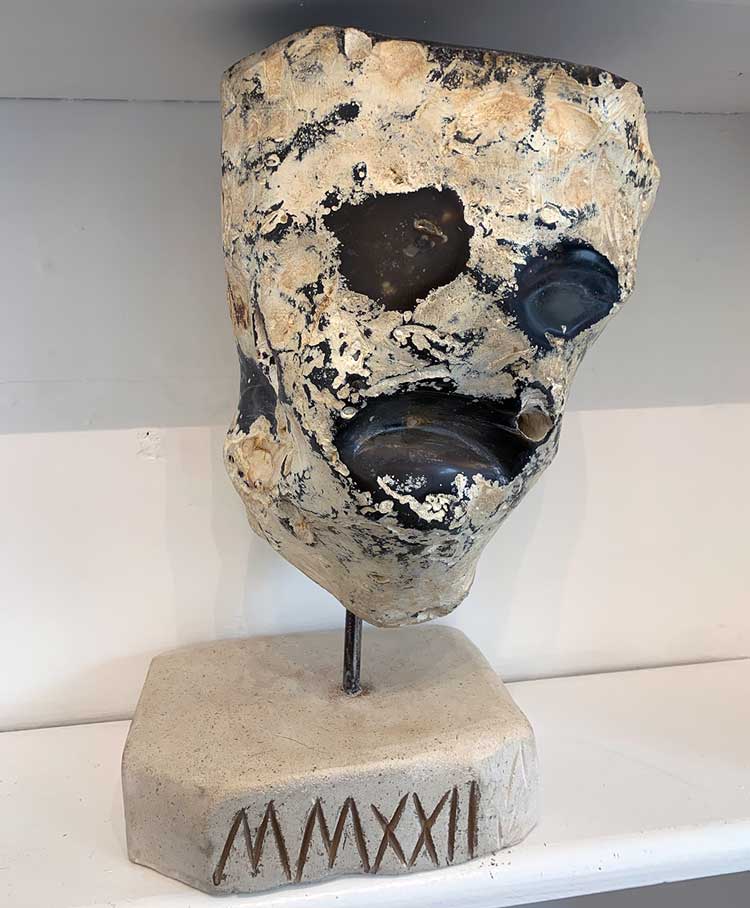

Drew Edwards, The Great Creator, 2022. Flint, 53 x 22 cm. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

In many of the works, including most compellingly in one of the strongest recent sculptures, named The Great Creator (2022), the eyes are a central focus. A 2019 monograph on Edwards’ work, with essays contributed by other artists, reveals how, in his early childhood, he was witness to extreme animal cruelty. His father ran Roebuck Farm, a quarantine facility in which up to 1,500 animals, including many primates, were held for supply to agencies such as the Ministry of Defence and pharmaceutical companies, for so-called research purposes.1 Edwards has spoken of viewing the imprisoned animals as a deeply traumatic experience: he has never forgotten the eyes of an orang-utan that, locked in a cage in front of him, stared right into him, as if in an empathetic transference.

Drew Edwards, Caged In, 2020. Flint, height 71 x depth 33 cm (27 15/16 x 13 in). Photo: Laurent Delaye.

In turn, one of most pointedly affective works in the present exhibition has the title Caged In (2020). We see a curved yet jagged-edged depiction of an open-mouthed creature, arms locked pathetically in front of its body, recalling the impact of the earlier event in Edwards’s psyche.

.jpg)

Drew Edwards, Small Putin, 2022. Flint, 43 x 21 x 16 cm (16 15/16 x 8 1/4 x 6 5/16 in). Photo: Bronac Ferran.

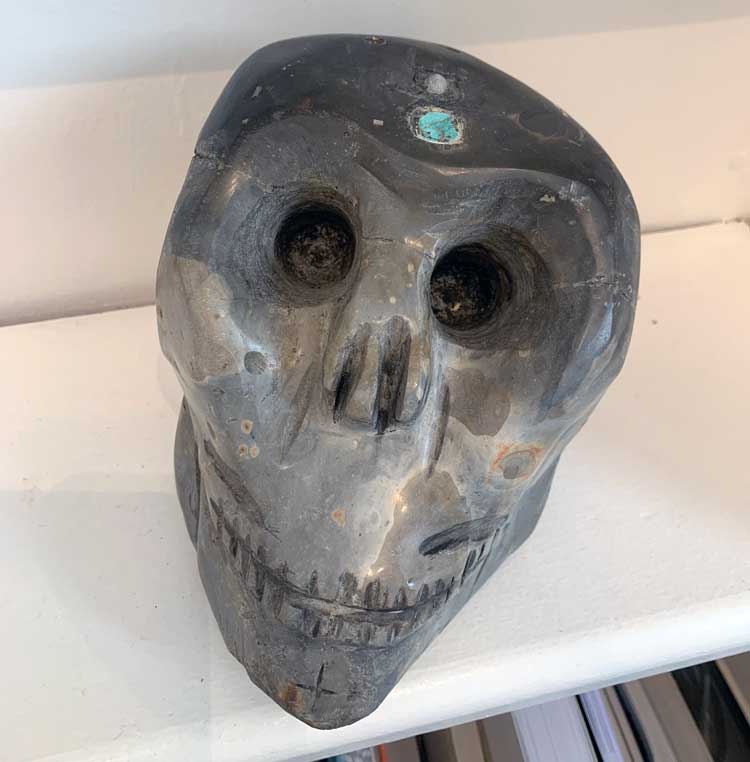

For Edwards, as a series of recent works reflect, sculpting stone is a political act. This, too, chimes with recent protests globally against the deification in monuments of historically discredited figures. This exhibition has two related works: the aforementioned depiction of Vladimir Putin in the work entitled Small Putin, with a head on which Edwards has placed the letter “Z”, synonymous with the act of aggressive invasion of Ukraine. A second work, Russian Soldier (2022), stares in a brutalised fashion, with eyes blackened out and empty of expression. It sits on the gallery shelves close to a skull-like work entitled Monkey (2017), which has two gouged-out holes for eyes.

Drew Edwards, Monkey, 2017. Flint, 15 x 15 x 21 cm (5 15/16 x 5 15/16 x 8 1/4 in). Photo: Bronac Ferran.

A sense of giving space in stone to the voiceless and those who are muted through human cruelty is also a significant theme running through Edwards’ oeuvre. This again may be traced back to the empathy he felt as a child with the imprisoned animals he saw in his father’s workplace. Although not in this exhibition, a sculpture by Edwards entitled Children of the Mediterranean (2017) is a monument to refugee children who have drowned in fleeing Africa to Europe. On public display at Middlesex University London, it features life-sized children carved from disused granite paving stones that were given to Edwards by the London borough of Barnet. The 91 figures, all without facial features, are chained together.

Edwards’ sculptures seem to me to embody and speak to a gap in the human psyche. As if refilling a vacuum, Edwards carves back into the nerve centres of human memory, extricating from some of the world’s hardest materials a sense of pathos. But the universe that he conjures in stone is one in which creation and destruction are closely embedded and the human figure is, at best, a brief glimpse of cosmic blue in a universe of fragments.

Reference

Drew Edwards: Shit Stinks But It’s Warm, London: Lotus Press, 2019, is available from Laurent Delaye.