Hetain Patel, Trinity (film still), 2021. © the artist. Courtesy the artist and Chatterjee & Lal.

Wolverhampton Art Gallery & Wolverhampton School of Art

22 January – 10 April 2022

by DAVID TRIGG

To encapsulate the previous five years of British art into a single exhibition is challenging at the best of times, but even more so when the period includes the extraordinary upheavals in politics, economics and technology that have occurred since 2015. This postponed ninth edition of the quinquennial British Art Show (BAS9) is presented against a complex backdrop of social and political turmoil rooted in Brexit, Black Lives Matter, climate anxiety and the Covid-19 pandemic. About 230 artists were considered by the exhibition’s curators, Irene Aristizábal and Hammad Nasar, who whittled their longlist down to just 47. Many are well known, others less so, but all are committed to probing the role of art in navigating our present moment, with results that reflect a shifting, uncertain and often chaotic world.

Installation view, British Art Show 9, 2021-22, Wolverhampton Art Gallery. Photo © Stuart Whipps.

This is the second leg of the ambitious exhibition, which launched last year in Aberdeen and will tour to Manchester and Plymouth later this year. For the first time, the show is adapting to each of its four host cities by responding to local contexts with different combinations of artists and artworks. In Wolverhampton, the focus is on “living with difference”, a suitably loose theme responding to the city’s recent cultural history, which has been shaped by its diverse population, particularly those who migrated from the Caribbean and other Commonwealth countries during the postwar period. The theme is ancillary to the three overarching ones that Aristizábal and Nasar identified before the pandemic struck: healing, care and reparative history; tactics for togetherness; and imagining new futures. These are unpacked in a considered catalogue essay, but drift in and out of focus across the exhibition’s two venues, Wolverhampton Art Gallery and Wolverhampton School of Art.

Hetain Patel, Trinity (film still), 2021. © the artist. Courtesy the artist and Chatterjee & Lal.

The British Art Show is an ambitious undertaking, which, despite the curators’ best intentions, can never truly reflect the breadth of current practice in the UK. Though their selection is strong, in Wolverhampton it is often hard to fathom connections between individual artists and there is little sense of any logical progression while navigating the show. Why, for instance, is Andy Holden’s installation of feline figurines sandwiched between Uriel Orlow’s research project on malaria remedies and Grace Ndiritu’s display of ecological activism? The curators’ fondness for self-indulgent video adds to a growing sense of fatigue (who has the time, or patience, for a five-hour film programme?), but it is among the preponderance of audiovisual works that some of the exhibition’s strongest moments emerge.

Grace Ndiritu, Plant Theatre for Plant People, 2021. © Grace Ndiritu. Installation view, British Art Show 9, 2021-22, Wolverhampton Art Gallery. Photo © Stuart Whipps.

Hetain Patel challenges assumptions about identity and ethnicity in his compelling film Trinity (2021), a coming-of-age story about a British Indian woman who discovers a mysterious lost language of physical combat. High production values continue in Lawrence Lek’s mesmerising CGI fantasy, AIDOL 爱道 (2019), focusing on the relationship between humanity and artificial intelligence; set in a world “turned outside-in”, it tells the story of a fading superstar singer who collaborates with an AI songwriter and asks pertinent questions about the potential of machines to aspire to beauty.

Lawrence Lek, AIDOL爱道, 2019. © Lawrence Lek. Installation view, British Art Show 9, 2021-22, University of Wolverhampton School of Art. A Hayward Gallery Touring exhibition organised in collaboration with galleries across the cities of Aberdeen, Wolverhampton, Manchester and Plymouth. Photo © Stuart Whipps.

Fantasy gives way to the sombre realities of war and conflict in Hrair Sarkissian’s outstanding sound installation Deathscape (2021), which fills a darkened room with the unsettling scraping and tapping noises of forensic archaeologists as they excavate Franco-era mass graves in Spain. The horrors are left to the imagination.

Installation view, British Art Show 9, 2021-22, Wolverhampton Art Gallery. Photo © Stuart Whipps.

Despite the recent resurgence of interest in British painting, only a handful of painters are included in BAS9. Hurvin Anderson’s compositions inspired by African-Caribbean barbershops are a highlight, and include Is it OK to Be Black? (2015-16), which confronts the viewer with images of black political icons tacked to a barber’s mirror; other, more abstract works show hair products and magazine clippings reduced to geometric abstractions. These are presented alongside Michael Armitage’s dreamy lithographs derived from his experiences in East Africa and Paul Maheke’s ghostly bleached fabric drawings, which are suspended from the ceiling and lit by the warm glow of elegant hand-blown glass lamps. Nearby, Alberta Whittle’s installation of copper printing plates and prints exploring colonial history in North America completes the thoughtful grouping. As one of the few instances where works are genuinely in dialogue with each other, this room is one of the exhibition’s most coherent and satisfying.

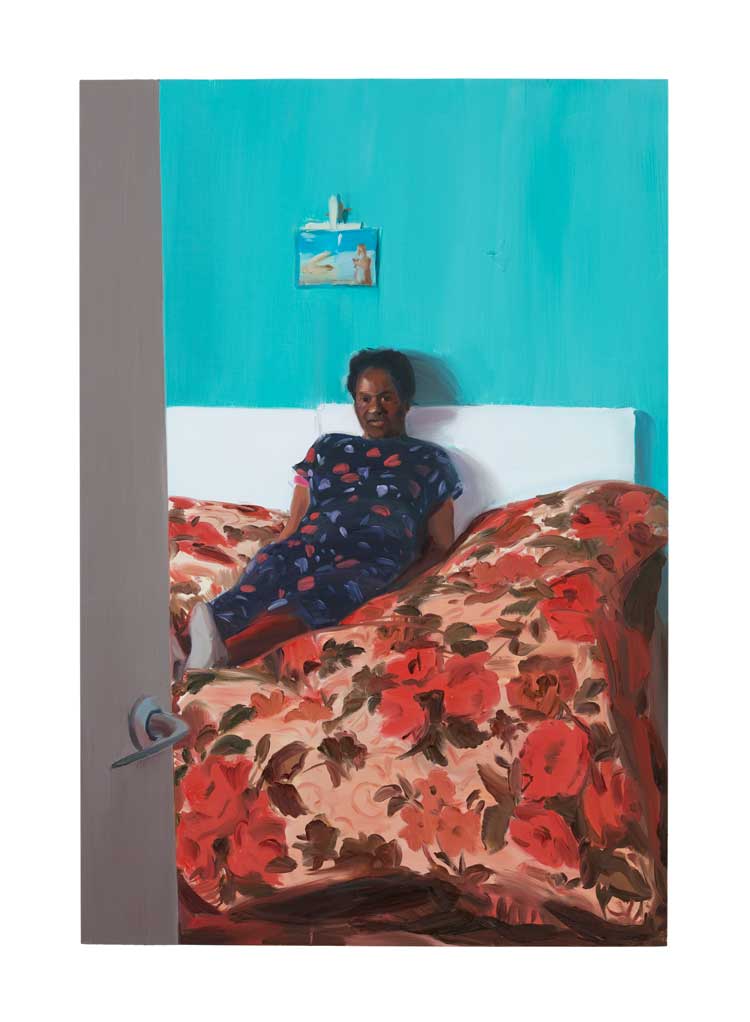

Caroline Walker, Joy, 11.30am, Hackney, 2017. Photo: Peter Mallet. © the artist and GRIMM. Courtesy the artist, GRIMM Amsterdam/New York, Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London.

Among the other painters in BAS9 is Caroline Walker, whose portraits commissioned in collaboration with the charity Women for Refugee Women are displayed at the School of Art. Highlighting the temporary living conditions of female asylum seekers from Africa and South Asia, these sensitive, painterly images seem well suited to the cramped student workspaces. It is certainly a bold move to host the exhibition here, yet it hardly shows these works in their best light. Perhaps it is the brick walls, strip lighting, and paint-caked floors masked by a fresh coat of frigate grey, but the works here feel compromised, especially when accompanied by wall sockets, radiators and sinks. The exception is Mandy El-Sayegh’s installation Blank Verse Blanket Man (2022), which, by covering the walls and floor of a room with newspaper and hospital green paint, ingeniously incorporates these elements into its sinister, cell-like environment.

El-Sayegh’s installation references, among other things, the “dirty protests” of IRA prisoners at the Maze prison in Northern Ireland in the late 1970s. In this, there is a resonance with Conrad Atkinson’s photographs documenting aspects of the Troubles, which are included as part of an engrossing display from Wolverhampton Art Gallery’s permanent collection. This show within a show also features works by artists linked to Wolverhampton’s Blk Art Group, such as Eddie Chambers, Keith Piper and Sonia Boyce. It teases out connections with the artists and themes of BAS9, setting the contemporary work in critical dialogue with that of a previous generation. Of course, much progress has been made since the 70s and 80s, but with racial discrimination still rife and the Irish peace process looking increasingly precarious, the concerns raised by these historical works have a depressing currency. BAS9 highlights the art of a nation that is becoming ever more aware of where it has come from and what still needs to change, but while many artists imagine more hopeful futures, there is little consensus on where we are headed.

• British Art Show 9, part of Hayward Gallery Touring, will travel to Manchester from 13 May to 4 September 2022, and to Plymouth from 8 October to 23 December 2022.