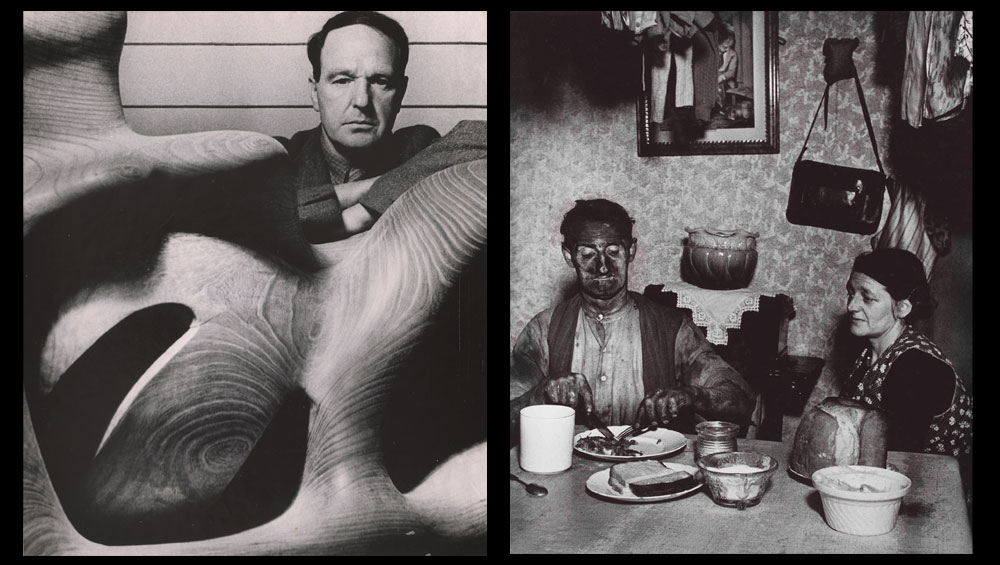

Left: Bill Brandt, Henry Moore, 1948, gelatin silver print, Hyman Collection, London, © Bill Brandt/Bill Brandt Archive Ltd. Right: Bill Brandt, Northumbrian Miner at his Evening Meal, 1937, gelatin silver print, Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York, © Bill Brandt/Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

Reviewed by BETH WILLIAMSON

I didn’t see the Bill Brandt Henry Moore exhibition when it opened at the Hepworth Wakefield in February. In March came lockdown in the UK and the venue closed. Ahead of visiting the reopened exhibition there, I have been fortunate to spend time with the accompanying publication.

This lavishly illustrated book is generous to its readers. With more than 250 illustrations, it is an absolute pleasure to turn its pages and it is clear that particular care has been taken in the design and printing of the book. Images of magazines are reproduced in their entirety as three-dimensional objects, making a more direct comparison with sculpture possible. The print finish, too, varies throughout, modulated according to the nature of the individual image, with newspaper images reproduced in matt and others in high gloss, for instance. This careful variation in perspective and finish makes for a more physical embodied experience of the images.

Bill Brandt, Normandy, 1959, gelatin silver print, Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York, © Bill Brandt/Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

Martina Droth and Paul Messier, the book’s editors, draw further attention to the materiality of the images by pointing out Brandt’s writings and markings on the verso of the photographs and noting how light reflects off the surface of a photographic print when you move it in your hands. Holding on to what they call “a residue of this experience” is something that the book’s design allows for very well. As they insist: “The experience of art through photography and the printed page is not subordinate or peripheral but central and unique.”

Henry Moore, Sleeping Shelterers: Two Women and a Child, 1940, ink and watercolour on paper, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, United Kingdom, photo by Marcus Leith, © The Henry Moore Foundation, UK.

This is no coffee table book produced simply for visual impact, as important as that is. There is a story to be told here of the intersections and parallels between Brandt (1904-83) and Moore (1898-1986), photography and sculpture, but it is more complicated than that. Moore made non-sculptural work, too – drawings, prints, textiles and photographs – and Brandt made sculptural assemblages as well as photographs later in his career.

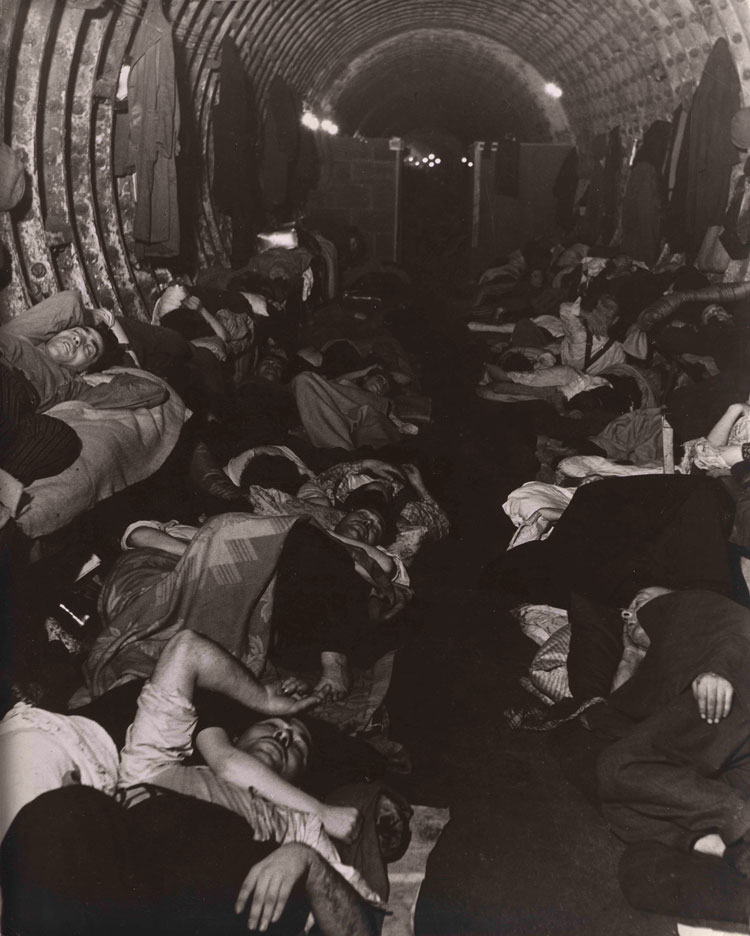

Bill Brandt, Liverpool Street Extension, 1940, gelatin silver print, Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York, © Bill Brandt/Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

This story circles around the horrors of wartime that provided both artists with compelling subjects. After all, the horror and destruction of war cannot be ignored, particularly for a photojournalist such as Brandt or a war artist such as Moore, whose job it was to document such horrors. Still, in the hands of Brandt and Moore, the miserable darkness of war becomes something plaintive and evocative, more than mere documentation.

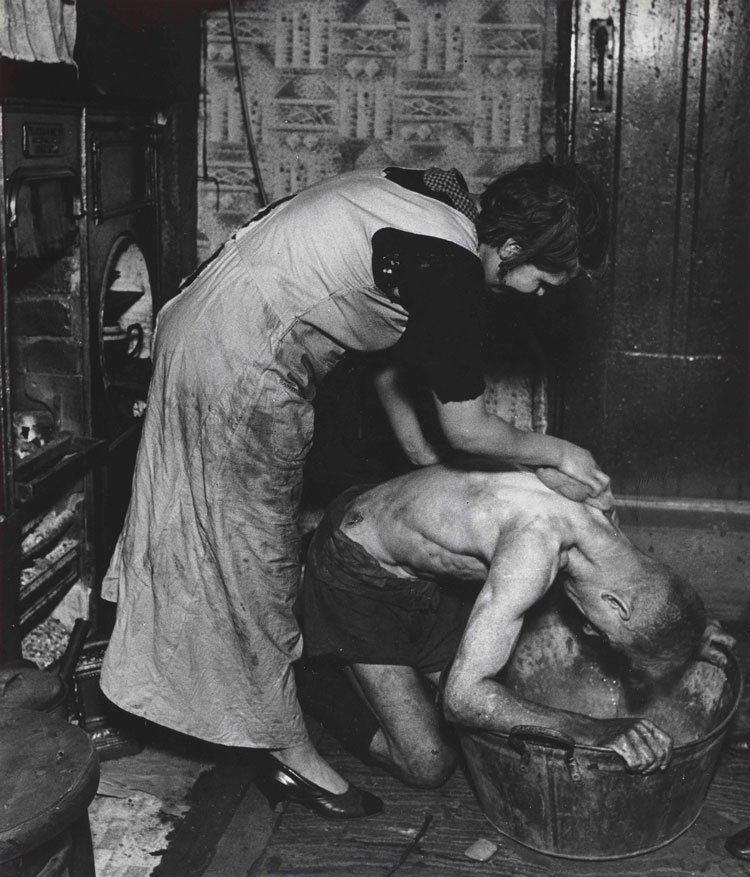

Bill Brandt, Coal-Miner’s Bath, Chester-le-Street, Durham, 1937, gelatin silver print, Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York, © Bill Brandt/Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

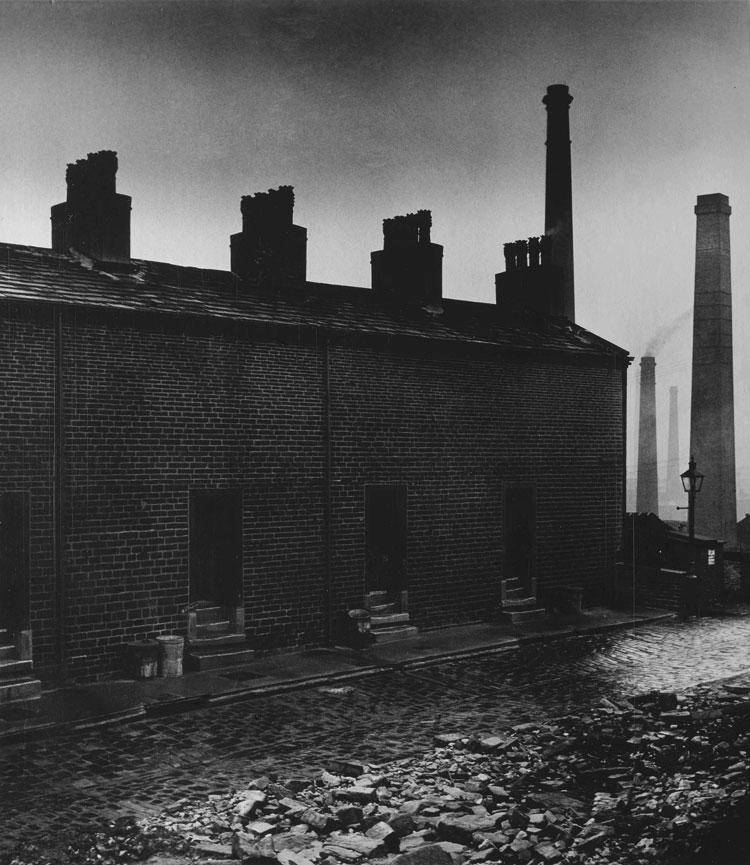

In the 1930s, Brandt’s images of London’s slum living conditions and families in poverty in the mining communities of the north of England resonated with Moore’s personal history as one of eight children in a Yorkshire mining family. Moore’s mining drawings use a shiny finish on charcoal to evoke the carbonite underground. He shows the constraints of a lack of light and space in a manner that conveys the oppressive nature of the environment for the miners themselves. In this sense at least, they echo Brandt’s mining photographs in their focus on human experience. Putting humankind at the centre of the domestic, working and wartime experiences they depicted, Moore and Brandt elevated their subjects. The gritty honesty of Brandt’s domestic scenes is very different from the ideal nuclear families sculpted by Moore, but both artists give “sympathetic portrayals of ordinary civilian experience”. The same might be said of Moore’s Sleepers, Londoners sleeping in the underground during the blitz, where gentle curves and soft colours portray figures in neat, comfortable rows. The equivalent figures in Brandt’s underground scenes appear chaotic and uncomfortable.

Bill Brandt, Coal-Miners’ Houses without Windows to the Street, 1937, gelatin silver print, Edwynn Houk Gallery,

Brandt and Moore also understood the importance of mass media in communicating their ideas. Through newspaper and magazine reproductions, the work of both men reached a wide audience. Their mutual understanding of volumes in space is underlined in Brandt’s photographs of Moore, the first of which, reproduced in Lilliput in December 1942, showed Moore in his studio. There is a suggestion that Moore used photography to lend currency to his abstract sculptures, to validate them in the eyes of the general public, and that may be so. However, Moore’s interest in photography was much more than that. As is well known, he used it for the purposes of documentation and record-keeping. He also used the medium to develop his own image as an artist, posing with sculpture closeup, out of doors and in the studio. Some of these images, such as those selected by Life magazine in 1959, depict the sheer physicality of the sculptor, or “stone shaper”, selecting 67 tons of marble from an Italian quarry or finalising a monument in situ. The physicality of Brandt’s photographic practice might not be as obvious as that of Moore’s sculpture, but Brandt is known for physical manipulation of his prints, adding pencil lines, incising with a knife, or brushing on dye or gouache.

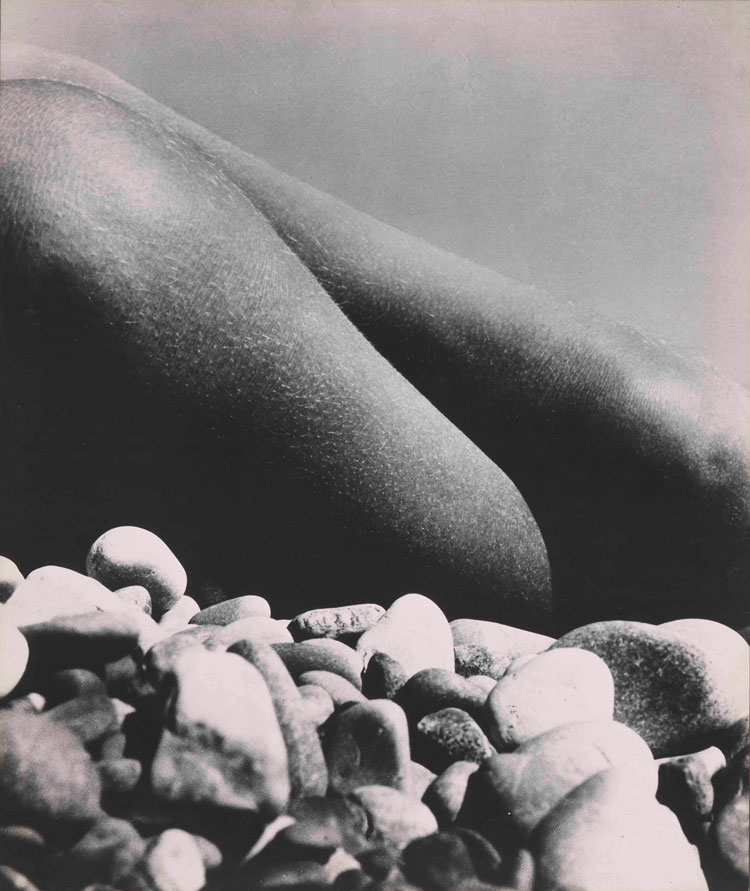

Bill Brandt, Nude, Baie des Ange, 1959, Bill Brandt Archive Ltd., London, © Bill Brandt/Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

Towards the end of the book, and decades into both artists’ careers, we see less well-known images – Brandt’s nudes and assemblages, Moore’s fragments, found objects and photo-collages. Still, the stars of this book are surely the pages of the Picture Post and Life magazines that we feel we could pick up and flick through. These images are so redolent of the real thing that the affordances of newsprint magazines quickly become apparent and we imagine the residue of printer’s ink they might leave on our fingertips.

Henry Moore, Family Group, 1944, pencil, wax crayon, charcoal, wash on paper, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, United Kingdom, photo by Marcus Leith, © The Henry Moore Foundation, UK.

This book is an excellent example of how to tell a story in word and image. It relates parallels and differences in their respective practices and perspectives. It is evident that the essays in this book have been deeply researched by their authors. They are written in fluent and accessible prose. They are engaging and use images not just as illustration, but as integral to their argument. That is why the book’s format, finish and design are so important.

• Bill Brandt Henry Moore, edited by Martina Dorth and Paul Messier, is published by Yale University Press, price UK £50, US $65.

• Bill Brant Henry Moore will be on view at the Hepworth Wakefield from 1 August to 1 November 2020, the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich, from 20 November 2020 to 28 February 2021 and the Yale Center for British Art, Newhaven, Connecticut, from 15 April to 18 July 2021.