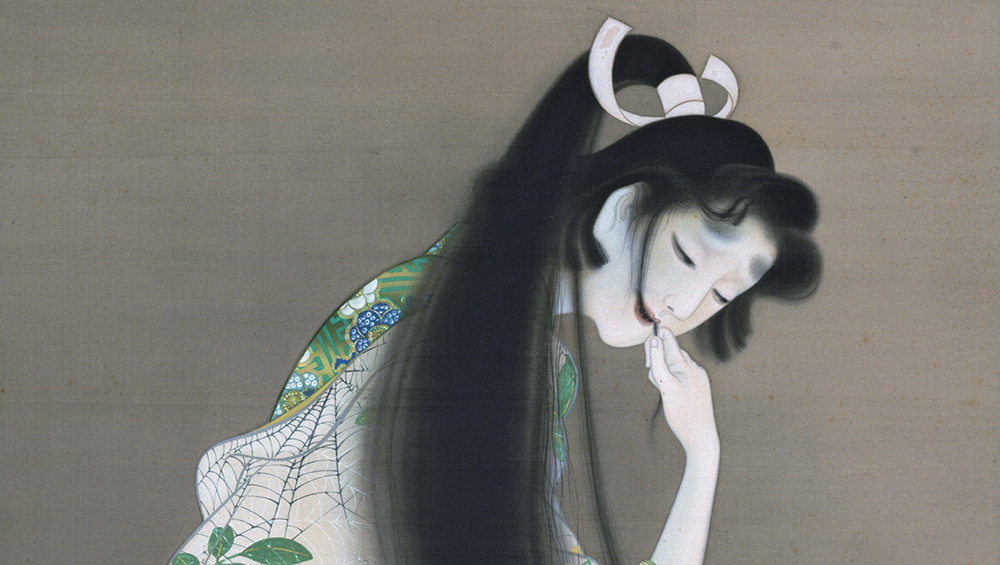

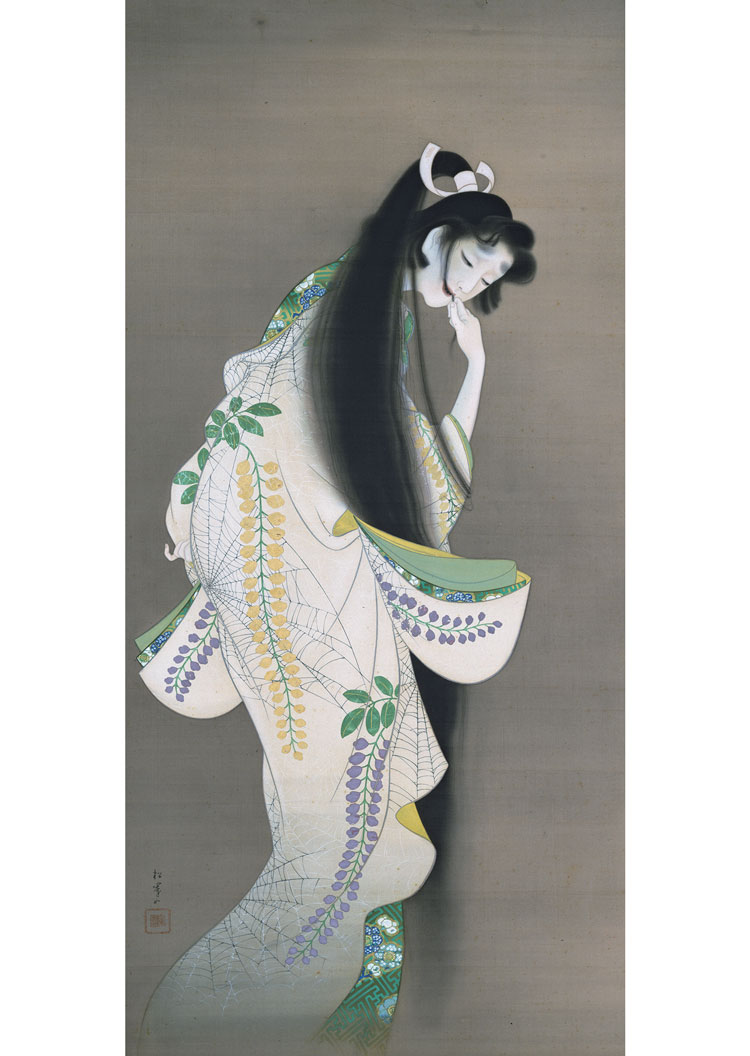

Uemura Shoen. Flame, 1918. Tokyo National Museum.

National Museum of Modern Art Tokyo, Japan

23 March – 16 May 2021

by KANAE HASEGAWA

Ayashii: Decadent and Grotesque Images of Beauty in Modern Japanese Art presents a diverse expression of Ayashii, the literal meaning of which in English is suspicious, but in this context refers to the mysterious, brooding, ghost-like, decadent or grotesque imagery of beauty represented in Japanese art produced from the late-18th to the early 20th century. The 160 works on show at the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo range from the 18th-century painting Beauty, by Soga Shōhaku, depicting a woman biting to shreds what appears to be a letter from her lover, to an early 20th century illustration of a femme fatale by Tachibana Sayume. Created to offer escapism from the harsh realities of a turbulent era, these occasionally grotesque and often seemingly scandalous paintings enjoyed immense popularity among the Japanese public.

Soga Shohaku. Beauty, 18th century. Collection Nara Prefectural Museum of Art.

Notions of beauty differ from country to country and change over time. In the era when the art in this exhibition was created, the Japanese public took pleasure in seeing pretty women in paintings as an entertainment, and artists explored various ways of projecting beauty. Some, like Soga Shōhaku, in Beauty, demonstrate a fascination with revealing women’s inner emotions.

Uemura Shoen. Flame, 1918. Tokyo National Museum.

Nearly two centuries on, Uemura Shōen, in her 1918 painting Flame, shows a similar theme, with a woman biting her hair in uncontrollable jealous rage. Japanese people felt empathy with the subjects of these paintings, which allude to the fact that it was often the woman rather than the man who had to endure abandonment by a lover.

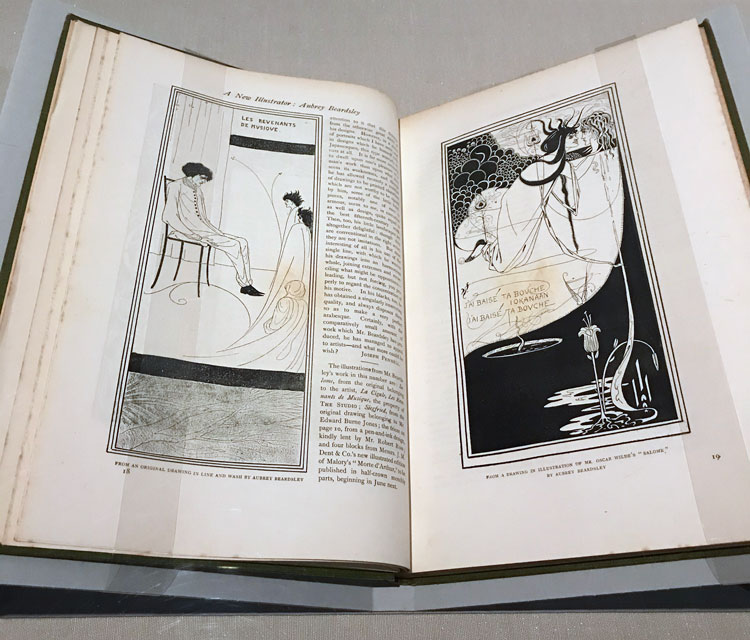

From the late-19th century, the Japanese notion of beauty was influenced by western ideas, as Japan opened its borders, allowing an influx of commodities and novelties from western countries. Japanese artists first came across the works of the pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Aubrey Beardsley through imported publications.

Painters such as Fujishima Takeji were enamoured with western art’s realistic renderings of people – which were different from the Japanese way of painting, devoid of accurate perspective – and the symbolic, sinuous lines seen in art nouveau paintings.

Fujishima Takeji. Lady with Morning Glories, 1904. Private collection.

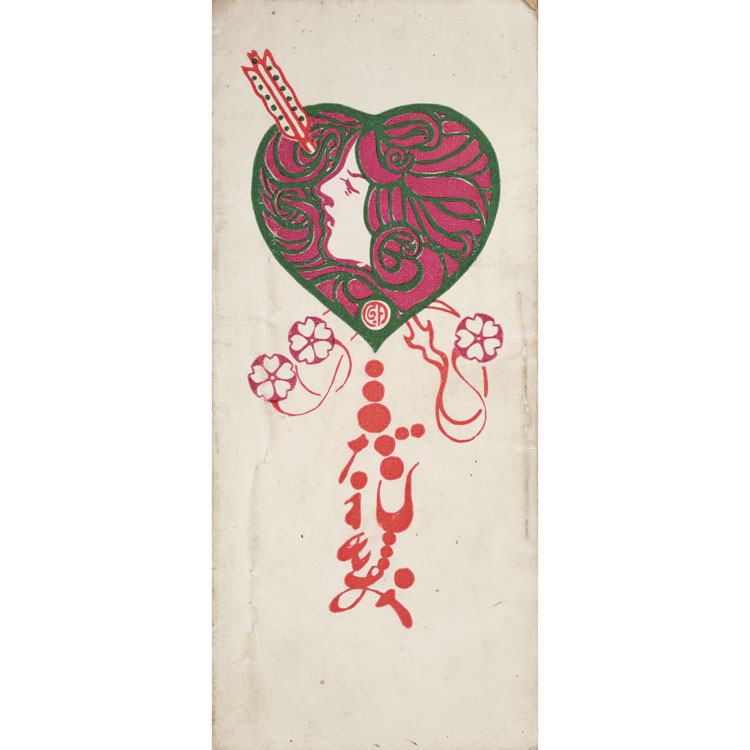

Fujishima Takeji is said to have mentioned Edward Burne-Jones’s influence on him, and it can be seen in the former’s painting Lady With Morning Glories, which depicts a languid woman gazing provocatively at the viewer. At the same time, the dishevelled hair of Fujishima Takeji’s female figure in the design for the cover of Midaregami, Yosano Akiko’s 1901 book of tanka, shows the influence on him of art nouveau artists such as Alfons Mucha.

Fujishima Takeji, design for book cover Midaregami, a book of tanka by Yosano Akiko, 1901. Collection Meisei University.

Images of the femme fatale from foreign countries provided Japanese artists of the same period with great inspiration in the way they depicted Japanese female beauty: culture became richer through appropriating different cultures. Many Japanese artists were enchanted to see illustrations of artists such as Beardsley, which were introduced to Japan through the literary journal Shirakaba, meaning White Birch, (1910-23).

Aubrey Beardsley, The Studio: An Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Arts, 1893, volume 1.

Artists saw Beardsley’s depiction of devilish and bewitched females with a fresh eye and eagerly incorporated his style into their own output. His influence was most prominent in the works of Tachibana Sayume and Mizushima Niou, whose fantastic renderings of mysterious females peopled his fantasy novels.

Tachibana Sayume, Anchin and Kiyohime, c1926. Collection Yayoi Museum.

Tachibana Sayume’s monochromatic painting Anchin and Kiyohime (1926) depicts the story of Kiyohime, a young woman who fell deeply in love with a monk named Anchin and pursued him obsessively. Realising he can never return her love because of his vows of chastity, she turns into a serpent, chasing the monk and finally burning him to death. It is a popular historic tale that has spawned many plays and has been a source of inspiration for artists throughout history, with each of them visualising their own fantasy world. In the case of Tachibana Sayume, who was dubbed the Japanese Beardsley, Beardsley’s illustration of Salome was an important source of inspiration.

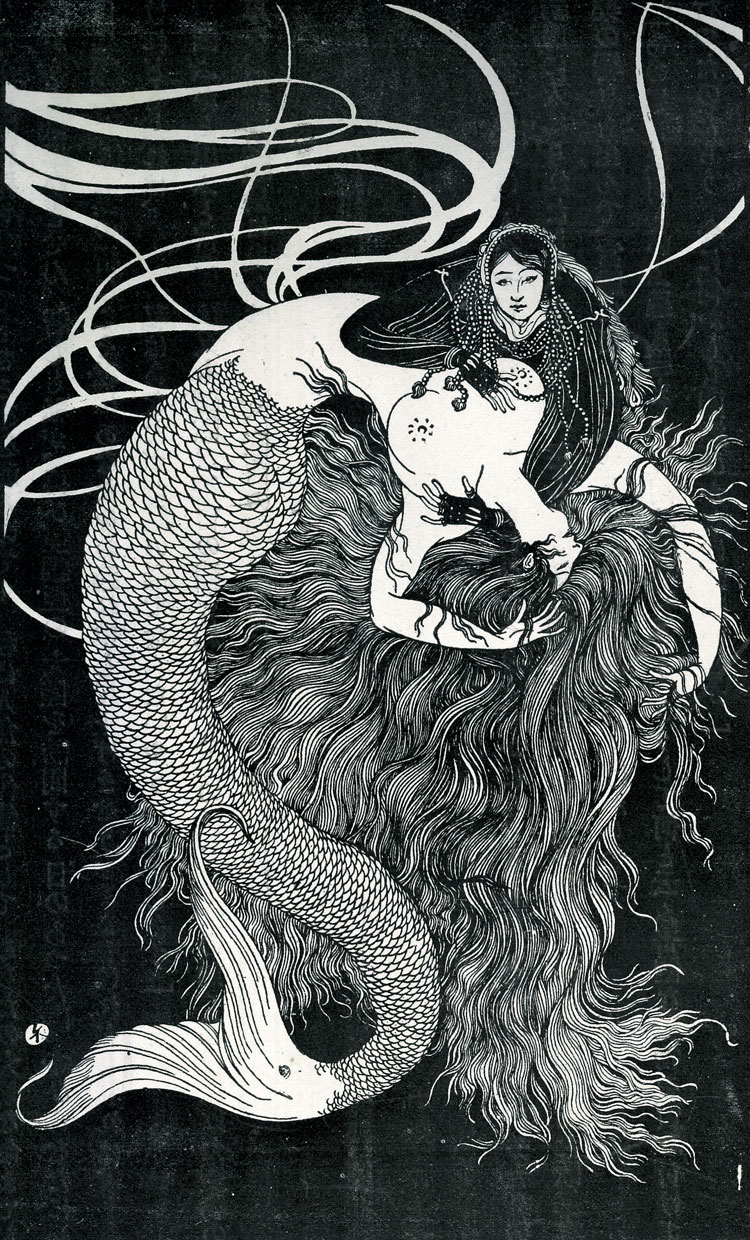

Mizushima Niou. Illustration for Ningyo no nageki by Tanizaki Jun'ichiro, 1919. Collection Yayoi Museum.

Other artists were influenced by different symbolic imaginings. The legendary mermaid was a recurrent theme for artists seeking to depict alluring women. In Japanese stories, the mermaid, which had appeared in the country’s documents since the fifth century, was said to have the power to give eternal life to those who ate her flesh. The Japanese novelist Tanizaki Jun’ichirō, best known as the author of In praise of Shadows, incorporated a mermaid in his novel The Mermaid’s Sorrow, while Mizushima Niou showed his skills in visualising the fantasy of the novel with his Beardsley-like illustrations of a mermaid enslaved by a human.

Komura Settai, Tattoo. Original drawing for an illustration in Oden jigoku by Kunieda Kanji (for Meisaku Soga Zenshu, vol. 1), 1935. Collection The Museum of Modern Art, Saitama.

There are several views on why the female figure was used to express jealousy, decadence, mystery or even demons. In Japan, in the past, the female was considered to be unholy and was not allowed in sacred areas. Such myths had led to women being seen as decadent, fatal for mankind.

In the 19th and early 20th century, Japan faced ordeals and uncertainties: there was political turmoil, riots, earthquakes and hunger. The late-19th century was a turbulent era: the US navy forced Japan to open up its ports to foreign trade, and the Japanese social system changed dramatically from feudalism towards capitalism. In such a world, people sought escapism from harsh reality in entertainment.