Art Without Frontiers: The Story of the British Council, Visual Arts, and a Changing World, by Annebella Pollen, published by Art/Books.

by BETH WILLIAMSON

When the British Council was founded in 1934, it was known as the British Committee for Relations with Other Countries, a somewhat cumbersome title that, by 1936, had already morphed into its current form but, nonetheless, remains a valid descriptor of the British Council’s purpose. Thinking about how that purpose is achieved, the present publication considers the visual arts arm of the British Council’s activities, its practices and objectives, though a close examination of its art collection – the British Council Collection – and its exhibition programme around the world. Art Without Frontiers considers the collection (its acquisitions, exhibitions and touring activities) as an exercise in international cultural relations that reflects Britain’s standing in the world and, perhaps, even acts to shape that standing. With unprecedented access to institutional archives, artworks, correspondence and personal interviews, Annebella Pollen tells the shifting and captivating tale of the British Council Collection, and the relationship between culture and politics, from its beginnings until the present day.

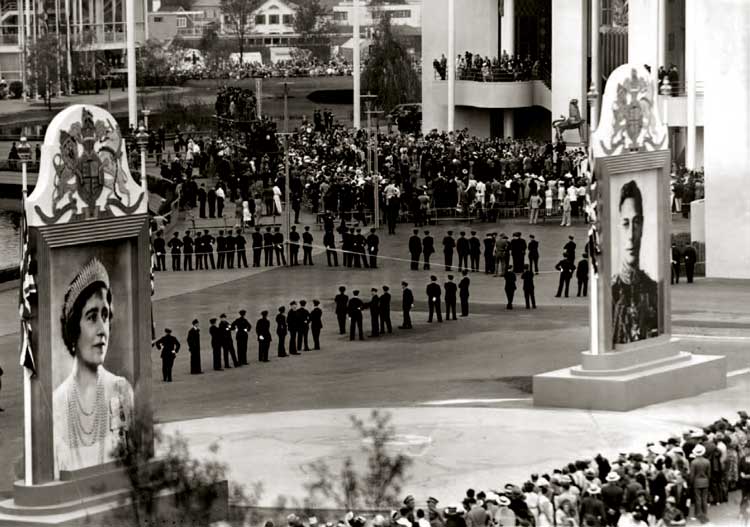

Huge portraits of Queen Elizabeth and King George VI and large crowds greeted the royal couple when they visited the British Pavilion on 10 June 1939.

The membership of the British Council’s Fine Arts Committee, meeting for the first time in 1935, mirrored that of the major national arts institutions and included among its number Sir Kenneth Clark, then director of the National Gallery in London. This prestigious committee dealt with requests for exhibitions across the world. Sometimes these were from countries with British Council offices, sometimes in support of diplomatic activities directed by the Foreign Office. Also within their remit were the large international events that called for a British presence – the Venice Biennale from 1937 and the New York World’s Fair in 1939, for instance. In the latter, any strategic political exigencies were referred to as “goodwill” and smuggled under the radar, as it were, in the form of an art exhibition that attracted 11 million visitors before war broke out in September 1939 – an indirect way to court American support and later war-time alliance.

A set of commemorative postcards was produced by the World’s Fair to mark the occasion and to extend the hand of ‘peace and friendship’ more widely.

Initially, the Fine Arts Committee had no collection to work with and had to borrow works for exhibitions from national institutions. The collection per se took shape from 1937 when the industrialist Lord Wakefield gifted funds for the purpose and what became known as the Wakefield Collection was born. With £1,000 a year, initially for the first three years, the committee largely acquired prints, relatively low-risk works to send overseas, but also useful in terms of their form and content to convey British cultural values of the period. What happened after that is the concern of this publication. As its author explains so eloquently, by examining visual art, the book “offers tangible evidence for the mostly intangible work of cultural relations”.

Ceramics displayed in the Exhibition of Modern British Crafts in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo © 2023 British Council Collection.

One early exhibition in 1942 was the Exhibition of Modern British Crafts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Sending huge numbers of craft objects across the Atlantic in the middle of a world war may seem like madness, but the council did so in order to share the rural, domestic and handmade with overseas audiences and a particular narrative of British tradition, modernity and industry. The exhibition conveyed a British national identity and toured 15 cities in North America. It was deemed so successful that a second exhibition was send to Australia and New Zealand postwar.

Sculptures and works on paper by Bernard Meadows in New Aspects of British Sculpture, the group show in the British Pavilion of the 1952 Venice Biennale. © Archivo Storico della Biennale di Venezia – ASAC.

After the second world war, the collection expanded, acquiring its first oil paintings in 1946 and its first sculptures in 1948. By the 1950s the Fine Arts Committee included the likes of Clive Bell, Herbert Read and Lilian Somerville. Attention shifted away from North America and key exhibitions were shown at the Venice and São Paulo biennials. It was the exhibition for the 1952 Venice Biennale, commissioned by Read, that introduced a new generation of British sculptors to Europe and the “geometry of fear” was born. By the end of the decade, the department’s ambitions for acquisitions and exhibitions grew. Developments in pop art and print media dovetailed with debates about democratising art. More artworks were made available to the Fine Arts department through an agreement with the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, which soon donated money for the collection to be expanded. There was a particular emphasis on buying the work of young artists such as David Hockney, who was still a student at the Royal College of Art when his Pigs Escaping from a Hot Dog Machine was purchased in 1961.

.jpg)

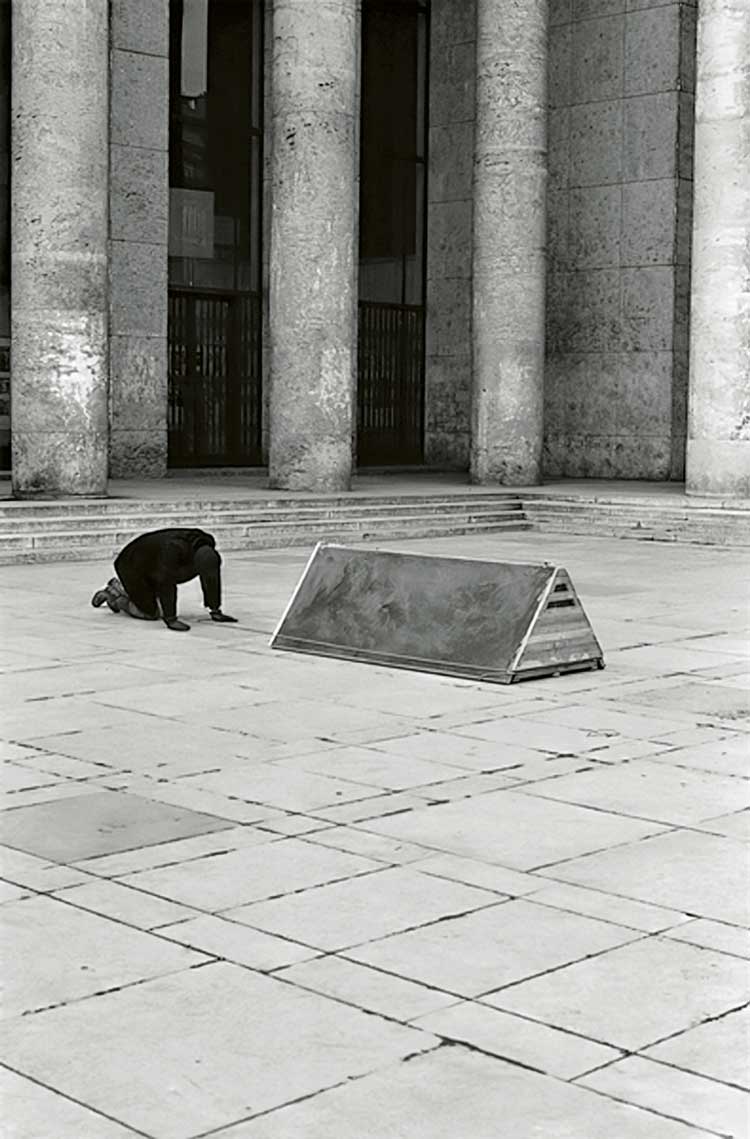

Kevin Atherton, The Audience’s New Clothes, 1979, performance at Un Certain Art Anglais …, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1979. © Kevin Atherton. Photo: Chris Davies.

In 1973, the UK entered the European Economic Community and the British Council refocused on European cultural relations while dealing with the challenges of new and expanded art forms. These included works such as Kevin Atherton’s The Audience’s New Clothes and Stuart Brisely’s Une Nouvelle Ouvre pour la Consommation Institutionel, both performed in Paris in 1979 and attracting critical press for the artists and the British Council. A change of government following the 1979 general election led to reviews, reorganisations and budget cuts within the British Council, and in the 1980s there were discussions about the value of art in cultural relations. These and other changes brought an expanding remit into the field of photography in order to expand the collection and support new exhibitions such as Inscriptions and Inventions (touring 1987-92) and Documentary Dilemmas (touring 1993- 96), both of which showcased contemporary British photography across western and eastern Europe and Brazil. In 1990, the Fine Arts department had been renamed Visual Arts, reflecting its widened scope and remit. A new generation of Young British Artists emerged and the Visual Arts department exhibition General Release (1995) shown in Venice was, according to Gregor Muir, the occasion for which the YBA shorthand was coined. Two years later, in 1997, the exhibition A Changed World, a reformatted sculpture exhibition, toured to Pakistan, raising religious and cultural objections to some works that necessitated their removal. This change, and the exchanges that followed, underlined the importance of cultural dialogue, not monologue.

Stuart Brisley, Une Nouvelle Oeuvre pour la Consummation Institutionel, three-day-and-night continuous performance, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1979. © Stuart Brisley.

With the new millennium came a reorientation for the British Council and activities to support cultural relations with the Islamic world. In the wake of the 11 September 2001 attacks (9/11) the exhibition Common Ground (already in development) commissioned work to help explore the range of experience for British Muslims in the UK. This included distinctive photographs by Suki Dhanda exploring the life of young Muslim girls and women in east London. Another exhibition, Turning Points (2004), was the first exhibition of British art to be shown in Iran and included artists such as the British-Iranian artist Shirazeh Houshiary, thus complicating ideas of nationality while presenting work that may be relevant the audience, especially the youth of Iran.

.jpg)

Suki Dhanda, Untitled, 2002, C-type print mounted on aluminium, 125 x 125 cm. © Suki Dhanda. Photo © 2023 British Council Collection.

The British Council’s 75th anniversary was marked with five exhibitions at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 2009 and 2010. Each exhibition was curated by a guest curator who brought a unique perspective to selecting works from the collection, helped by the scale and variety of the collection itself. More recently, that variety was underlined by the acquisition in 2019 of Delaine Le Bas’s work What We Don’t Know Won’t Hurt Us (Self-Portrait) (2006-18). The first painting acquired by the collection was Duncan Grant’s Charleston Barn (1942) which, as should be remembered, was painted by in wartime by a conscientious objector, just a few miles from the English coast where invasion was expected. So, as Pollen points out, that variety and diversity was there all along.

The fascinating thing about this book is that it doesn’t just tell the tale of an institution over nine decades. More than that, are the personalities, events and contexts that enrich and enliven the story. Towards the end of the book is a full-page image of the blue packing cases used to transport the British Council Collection works around the globe. In many ways an innocuous image, it somehow galvanises the narrative. As Pollen observes: “Art is a highly invested category that can evoke strong emotional reactions.” It is a reminder, if it were needed, that the story isn’t over, the collection continues to be shipped around the world for exhibitions, and the political and cultural work of the British Council Collection carries on. If you want to understand that work, its beginnings, development and current state, then this book is a perfect place to begin.

• Art Without Frontiers: The Story of the British Council, Visual Arts, and a Changing World, by Annebella Pollen, is published by Art/Books, price £29.99 (hardback).