CryptoPunks. Screenshot, Lava Labs, 2021.

by JILL SPALDING

On 23 January 2021, live and in real time, a pipe-smoking CryptoPunk, one of an edition of nine non-fungible token (NFT) algorithmic Aliens sold to the collective FlamingoDAO for 605 ethereum (ETH), the equivalent of about $850,000 or £609,280. Two days later, a second one sold for $2 million. Collectors vying to possess their top-selling companions – Zombies, Beanies and Apes – justified the transaction as a solid investment, since each of these pixellated images is unique and posted for all time on the ethereum blockchain; only 10,000 such creatures will ever exist, and their provenance, proof of ownership and attributes (“cap”, “mohawk”, “tiara”) are cryptographically recorded and readily monetised. The artsphere’s myriad blockchains are flooded with clever contenders, but Punks’ primacy as the first NFT images stored and traded on an unassailable blockchain places them and their owners in the pantheon.

CryptoPunk 7804, sold for ETH4200 ($7.5 million), 10 March 2021.

Pushback against such exalted status begs the question, how did collecting get here? For me, the day dawned when I learned that the seller of said Aliens was a colleague, that he had acquired them two years earlier for $55, and that his “wallet” holds 305 more of these digital creatures. “A great purchase,” tweeted fellow collector @gmoneyNFT, assigning that seemingly irrational acquisition to the same conspicuous consumption syndrome as humans manifest in the physical world. For the larger question of how did art get here, best begin at the beginning.

By the mid-1960s, predating icons and cursors, visionary artists at the Slade School of Art in the UK and Bell Labs in the US were producing computer-generated imagery at the level of Leon Harmon and Ken Knowlton’s Nude (1967). The art world took scant note until decades later, when artists such as James Faure Walker included digital art in their paintings, and Harold Cohen premiered Aaron, a robotic paint software program used to draw on large sheets of paper. More intriguing, though, for artists than for galleries, digitally rendered images remained curiosities until improved skills created the masterful videos that opened collecting to the digiverse.

Evolution but not breakthrough. Trace the techtonic shift to 1983. I was researching an article for UK Vogue in Los Angeles titled The Last of the Red-Hot Smokers when its gonzo protagonist, Hunter Thompson, introduced me to Timothy Leary. Leary invited me and my 11-year-old son to dine with him, his wife Barbara, and their young son, Zack, in order to show us his latest obsession. We were led to a small darkened studio of sorts, where a very young Jaron Zepel Lanier (now at Microsoft Research) was manipulating gloves wired to a green screen to create a seemingly random sequence of images – clearly super-cool, though we had no idea that what we were viewing was the dawn of the metaverse. Lanier’s genius achievement had averted today’s clumsy Oculus Rift headset to insert his humanity directly into the images. The technology, however, being prohibitively difficult and expensive, was ahead of its time, leaving video to constitute the bankable medium until its creative potential reached its limits. Ready to take over, the revolutionary blockchain database opened a generation raised on pixels to the concept of art that can be for ever accessed, collected, viewed, displayed, stored and tokenised in NFTs.

Early efforts were tentative. In 2014, the French artist Youl created an NFT one-off, The Last (Bitcoin) Supper, and sold it on eBay for a then unimaginable $3,000. A host of unattributed silliness followed – cartoons, dervishes, even tweets – most of them freely downloaded until 2017, when the infamous CryptoKitties were posted for sale and almost crashed the ethereum network, triggering a fever for crypto-collectables so widely transacted that tracking them has become in itself an artform of sorts. Traditional artists climbed aboard with fungible hybrids. Andrés Reisinger took a crash course in industrial design and created biomorphic furniture that could be “collected” on a digital platform and either placed in a 3D metaverse such as Minecraft, or fashioned into physical objects. The first 10 sold in under 10 minutes, on the Winklevoss twins’ online marketplace Nifty Gateway, for an impressive $450,000: the most expensive was a unique piece to be co-created with the buyer. The year 2020 saw a rash of lucrative offerings designed by such colourful names-to-know as FEWOCiOUS, Giant Swan, DJ deadmau5, M&M, and Mad Dog Jones. Avid collectors moved to more sophisticated algorithms such as Dmitri Cherniak’s Ringers (generated in Javascript in the browser: total minted, 1,000), each output derived from a unique transaction hash and featuring a different variation (sizing, layout, orientation) of the infinite number of ways to “wrap a string around a set of pegs”.

Dmitri Cherniak, Ringers. Twitter screenshot, 19 March 2021.

Where, though, in all these postings was the art? There and not there, viewable and intangible, at once an image that can be projected on to a wall and the metaphor for an image that is, essentially, code. Because blockchain artworks are impossible to damage, steal or copy, the sudden need to own one handed collectors another collectible commodity and gave the world, very arguably, a new art form. While CryptoPunks started it and shall ever be the gold coin of the realm, even nameless artists found a home on the blockchain. Already, more than 70,000 of their pixellated whatnots have sold for well over $100m, confirming NFTs as the future not only of digital art but all digital property – in Flamingo-speak, “the tip of a very large spear” – and, as I propose, a new paradigm.

Like it or not, just as NFT JPEGs have upended the historical canon, so have they challenged the physical show space and scrambled – indeed, reversed – the roles of artist and patron. Firstly, by eliminating all who stand between creation and sale – dealers, agents, art advisers and art critics. For the digital artist, with no one taking a cut, and with no need for a physical studio, work transacted on the blockchain is pure gravy, generally garnering 100% of the initial sale and a 10% royalty every time it’s resold. In February, on short notice and over 48 hours, the music and video artist Claire Boucher, AKA Grimes, earned more than $6m for 10 pieces; two of them, Mars and Earth (digital videos in editions of 300), sold for $7,500 each, and one, Death of the Old, built in a bidding war to nearly $400,000. On 1 March, the first iteration of Matt Furie’s cartoon frog, Homer Pepe, sold for $312,000. On 3 March, electronic dance music star Justin Blau realized $11.7m from 33 NFTs giving access to new music, a custom song, new versions of old songs and a real-world vinyl disc. On 7 March, Dream Catcher, an eight-piece collaboration between Hamburg graphic artist Antoni Tudisco and dance/music producer Steve Aoki sold for $4.25m, its star attraction – “hammer” price $888,888 – a 10-second clip of a moving hirsute head titled Hairy. Trading briskly on multiple platforms is the crypto-artist Pak, creator of the AI-powered image-sharing site Archillect (his identity so obscured that he is rumoured to be an AI). Even lower-profile artists such as Mario Klingemann, Robbie Barrat, Trevor Jones and José Delbo have been selling in the six figures.

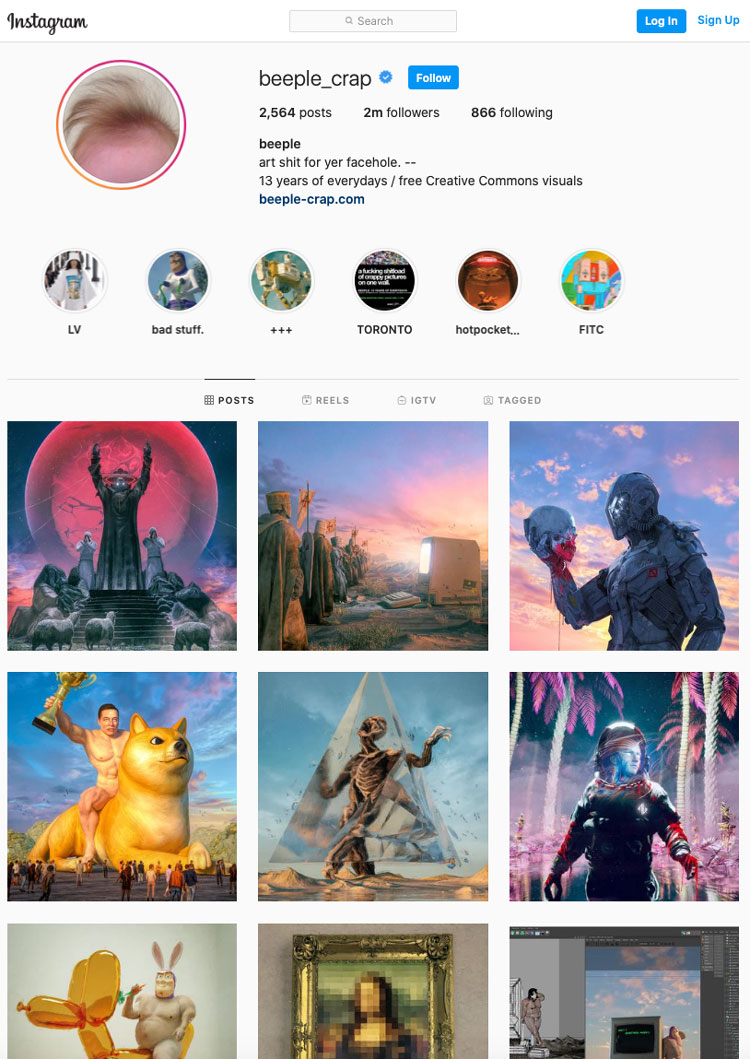

Madness? Not for the “woke” generation. Like the boomers with baseball cards, they are comfortable investing in any meme living and trading on a blockchain – sports clips, flying French fries – any image that amuses. Crypto art, they will tell you, is fun and fabulous. As Aoki said in a press release: “NFT’s gave me an opportunity to finally merge art, collectible culture and music in a way I’ve never been able to realise before.” And no need to bet the farm. A $100 investment bought into a 40-member fund with 4,800 ETH in pooled capital and an extensive collection that includes “landplots” in various metaverses. A mere $15.50 delivered collective ownership of B20, a work by the currently hotissimo crypto-artist Mike Winkelmann, moniker Beeple, which fast doubled its value.

The medium being the message, ether-art should not come as a shock. Even for boomers, TV viewing morphed so quickly to streaming that when the New York Times dropped its TV guide it lost few subscribers. With high-profile collectors of traditional art such as Elon Musk and Mark Cuban signing on, and with Gen Alpha communicating almost exclusively on crypto-channels, closer than predicted is the day when we all will be experiencing art in a virtual world.

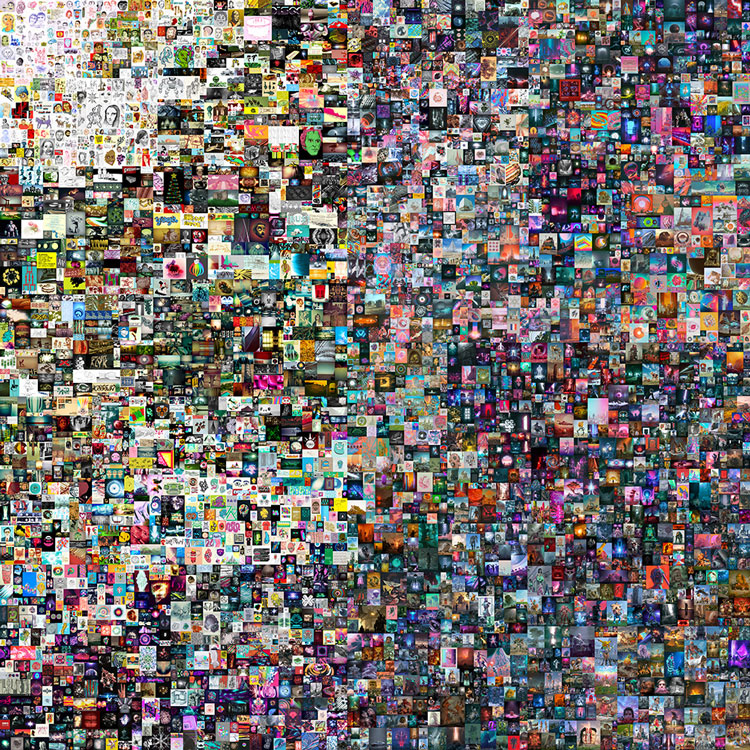

Mike Winkelmann, aka Beeple, Everydays: The First 5000 Days, Non-fungible token (jpg), 21,069 x 21,069 pixels (319,168,313 bytes), minted on 16 February 2021.

Most telling is Beeple’s coronation at Christie’s on 11 March, when Everydays: The First 5000 Days – a computer collage of digital drawings created singly every day for 13-plus years, minted exclusively for the auction house, and deemed by the pseudonymous buyer, Metapurse founder Metakovan (Vignesh Sundaresan), “the most epic cultural project and event to happen in the metaverse to date” – topped the December 2000 $3.5m sale of Winkelmann’s bundled works and crushed the $6m sale of his 10-second clip portraying people walking past a dead Donald Trump, to close at $69.4m, the third-highest price paid for a living artwork by a living artist. Although the conceit is not new (think On Kawara’s one-a-day paintings) and the work is a “hash” of off-chain images (unsatisfying for purists in that the collage itself is not on a blockchain), the monetary return crowning the newly minted masterpiece has dramatically widened the opportunity for collecting. So has the gravitas of the first-ever auction to be given entirely to crypto art and to accept crypto payment – the papal-blessing equivalent of Goldman Sachs trading bitcoin – set a new bar of sorts. Even Winkelmann was stunned: interviewed mid-sale by Jeffrey Brown for US broadcaster PBS, the self-styled designer described his “not-for-everybody” pop culture postings as “weird stuff”, and the term artist as “super-pretentious – I can’t even say it!” His bewilderment was humanising, and, for me, hearteningly gonzo. But he may be the last of the first.

@beeple_crap, Instagram, screenshot, 19 March 2021.

Already Damien Hirst, ever ready to jump on the new thing, has announced that he will accept cryptocurrency for his new run of prints: “I love the crypto world.” How long can it be before he, or David Hockney or Jeff Koons go crypto? And how, then, will NFT work by old-school artists be valued? Think back to the installation Agnes Gund funded at the MoMA consisting of six interactive flowcharts by Peter Halley that were physically displayed on walls specially built for them. Viewers segued to a massive computer (this being 1997) programmed to show all the images plus a digital pen and palate, and were invited to create an original work filled in with their colours of choice; to download it, co-sign it and, with Halley’s name pre-printed bottom left, co-sign on the bottom right, and take the work home. Calculating the limited number created (given computer breakdowns and the installation’s short duration) and the considerable number destroyed (I saw one in a bin on exiting), I estimate that my work might now be worth $200. Say that the next person to fill in, download and co-sign one had been Jasper Johns, its current value would eclipse all. In the metaverse, though, perhaps not.

Ascribing monetary value to an image is not, of course, to anoint it as art. Asking what might qualify it as such begs the time-immemorial question of what constitutes art? Marcel Duchamp famously said that art is whatever he hangs in a museum. By that measure, note ZKM (Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe), the bricks-and-mortar museum known as the “electronic Bauhaus”, whose mission is to take the spatial arts of painting, sculpture and photography into the digital age. Last year, the art marketplace SuperRare launched a crypto art museum on Decentraland, and the first-ever NFT art exhibition is opening soon at the UCCA Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing. Unless the Whitney muscles in with a Crypto Biennial, such venues are where collectors will be scouting new artists.

Not all are on board. Many the sceptic who attributes the wild action to frenzy, that bane of the tulip moment that may fold blockchain transaction into our long history of bubbles. Before all, they caution, crypto investment depends on a universally accepted gold standard-equivalent currency: in the crypto winter of 2018, digital assets took a spectacular fall, providing another tale of emperors with no clothes. But with the zeitgeist become blockchain, note the cryptophiles, cryptocurrency soon recovered, rescued from the nebula of mafia transactions by such knights in shining bitcoin as Jamie Dimon and David Solomon.

They blazon that crypto art is on sure ground because coded images, the visual language of the metaverse, are valued according to ancient rules of collectability; authentic, rare, unique and, above all, “first”. If aesthetics have been sidelined, has not the ideal of beauty been dying the slow death of beautiful-to-you-not-to-me since diversity and identity started eating away at the classical canon? And if a heavily retouched – indeed disputed – Da Vinci can fetch $450m, is it so wildly out of line that an Alien sold for $7m?

Heady stuff, so what gives pause? Most immediately, a lack of clarity – the tangle caused by craze: pure or impure; people or avatars; galleries or sites, and bidders who present as pixels like the prominent DeFi (decentralized finance) personality @0x_b1. Troubling that, in the supposedly freewheeling online marketplace, the digital collectibles site Rarible censored top-selling conceptual/appropriation artist Rulton Fyder on grounds not disclosed. Disturbing, too, are the criteria marking crypto art as collectible. If aesthetics are irrelevant and if no-name creators who sell well are held artists, then value derives largely from community-conferred status. Add in the hoarding syndrome recalling the Nahmad brothers’ stash of Picassos parked for lucrative resale; the unnerving whiff of big business – call it crypto-corporate – attached to SPACs (special purpose acquisition companies formed to take blockchain entities public); and exclusive crypto-funds such as Metapurse, which bundle works, then sell, loan or store them until their value skyrockets. Heavily invested in Dapper Labs’ blockchain Flow, for example, alongside National Basketball Association players such as Spencer Dinwiddie, JaVale McGee, Aaron Gordon and Andre Iguodala, are the crypto firms Coinbase Ventures and BlockTower Capital.

Why, then, a new paradigm? What places crypto art light years beyond today’s diversity and identity art? Although it’s unlikely that a tokenised Kehinde Wiley or Kara Walker will be inhabiting a digital museum any time soon, and no one – even should canvas look suddenly dated – will be throwing out the Warhols with the bathwater, the concept of blockchain-produced art is gripping and addictive. Yes, the techniques are replicable and the talent surpassable, but the metaverse has opened new worlds. Even neophyte collectors can avoid the tumble down the fastest-way-to-lose-your-shirt rabbit hole by scouting the first, the rare, and the visually stimulating, safely cushioned in pride of ownership and primed for the future. Groundbreaking, too, a system that guarantees authenticity (it’s been estimated that 20% of the art in UK museums is fake), obviates the hassles of shipping, insurance, storage and legal costs of moving physical art, and gives collectors wide Instagram access to galleries and power brokers heretofore invested in running the art world like a club.

Still, as with life itself, where there’s a yin there’s a yang. How long will the sophisticated collector be satisfied with owning nothing more than an entry on record? Won’t we pine for communal viewing in physical spaces? There is also the seriously limiting factor of network capacity – the for-now inescapable environmental impact of material created and stored on a blockchain. The energy exacted to transact 303 editions of Grime’s Earth was estimated to equate to the electricity the average EU citizen uses in 33 years, and produced 70 tonnes of CO2 emissions. That, counter the tech-savvy, is for now. Blockchain engineers are scouting alternate sources, and the art-centric envision fast-evolving new technologies that will decentralise and reshape the entire art market apparatus. Bricks and mortar museums, galleries and art fairs are already designing compelling new formats for display in soon-to-be-realised physical worlds of interactive, immersive engagement.

My caveats differ. I have no quarrel with a creative expression that can be endlessly reproduced, easily downloaded and handily monetised on a blockchain. I applaud returns guaranteed in perpetuum that enable artists to have agency, and the programmable scarcity that gives their work value. And I think it efficient – even healthy – that globally connected digital marketplaces combine the functions of gallery, museum, auction house and social platform. Commendable, too, is an ecosystem that brings transaction out of the secretive mega-gallery penumbra into the light of a community platform. I wonder, however, about the selection process; submissions to SuperRare, for example, are critiqued on its editorial and vetted by committee – well, by whom? For the neophyte, sans art historian or curator, what replaces the trained eye? And how can the crypto-collector who buys on an Instagram-style social feed not be influenced by its influencers – crypto enthusiasts more interested in pop than in quality?

More urgently, what does crypto art bring to the table? For the collector, status, of course, plus provenance, security, transportability and proof of ownership. For the artist, elasticity and no middleman. And all note the ease of display – dandy that work can be flashed on a wall, screen, mobile phone, or the palm of your hand. But in the virtual world, display is not really the point. Rather, it’s the high delivered by lightning turnover and rocketing prices that has taken crypto art mainstream. As that dedicated owner of Crypto-Punks said of his “purely as speculation” investment in a fractionalised piece of the bundle of 20 Beeple works that, on 9 March, reached $90m, crypto art speaks to “gambling for sure”.

My larger concern is with the ever-expanding definition of art. Reflecting on art is my profession, but takes up less of my bandwidth than feeling it. At the moment of encounter, I don’t deeply care about provenance, monetary value, historical importance, or place in the canon. A work that I interact with must reach out to me: if I don’t experience it, I move on. “The earth moved,” Hemingway’s sign of passion, is my key to art. Like love, art must course through my veins. While I can stretch the membrane to embrace performance art, and have become fond (the word is soft but accurate) of graffiti, I don’t respond viscerally to virtual world silliness such as pixellated wizards, the galloping Nyan Cat, and the zillion other VR memes developed overnight to shape the social experience.

And thereby the caveat. Does a geolocated pixel Kaws’ Companion elicit the emotion of Rembrandt’s The Jewish Bride that brought Van Gogh to tears? As with holography, the art medium that flamed in the late 1970s (Louise Bourgeois, Larry Bell, Ed Ruscha) but soon sputtered, something fundamental has been lost in all this fungibility, and I cannot but think that it’s the art. While I welcome the infinite visual possibilities opened up by the metaverse, seeing quality cede to scarcity, and art appreciation move from wall to wallet, I find myself pleading with the Art God to give me back a painted surface which, at a brush-length away, I can stand where the painter stood; a sculpture that I can run my hand along where the sculptor did. Even a photograph, so removed when first proposed as art, invites the eye to focus in on it like a lens.

These concerns are generational, of course. The young are programmed to vibrate to algorithms: coded images speak to them; shared ownership comforts them. Whereas for the old guard, owning great art is emotional and trading it is transactional, for the crypto art collector the distinction is arcane – the two co-exist seamlessly. The analogy of progressive eyeglasses is helpful: the art exists on the wall and in the wallet simultaneously. Had Rothko refused a commission because his paintings were to hang in a restaurant? Meaningless. The blockchain is not a venue, it’s ether – and that is the thrill. It may seem that this natively digital platform has upended art, but it is not art that is morphing, it is humans. Along with the expansion of art’s definition in the metaverse, how we experience art is evolving, ceding art appreciation to art’s appreciation. Now, only a work’s hype and tagging motivate purchase. Now possession alone and ownership’s endless possibilities of gamesmanship confer status. There is no denying the psychic high of flexing a rare collectible, placing a bid on a social feed, and interacting with a work instead of “just looking” at it. My colleague explained it this way: “It’s the rush of the frontier – being first to encounter and grasp the import of a new artefact – in this case, one that constitutes art by having been crafted by an artist. Add to its collectability that it’s unique, its ownership registered as mine on the block chain. It’s liquid – my entire collection hangs in my iPhone. It’s hassle-free – no concerns about protective glass to prevent fading. And it’s fun – I can flash individual images on a wall-screen, show them around, trade them, build on them, deal them.” To add to his collection, he trawls the net to find a slacker who has underpriced a Zombie or to see what’s on offer in the eponymous plot created by “whale” game designer Pranksy in the ethereum-powered virtual-world Cryptovoxel. “And, should I decide to sell one, there’s no middleman to deal with, no dealer or auction house.”

Tellingly, he has already pounced on the new thing – Autoglyphs! Thrillingly “on-chain” (chain-generative), this breakthrough generation of images, although created by the artist, remains random, not fully existing until realised on a blockchain. The code itself is the actual work, enabling virtual images that, although tiny, since coding them larger on a blockchain is economically unfeasible, are also (think a crypto-Sol Lewitt) actual and instructional – and thereby, very arguably, constitute a new art form, so prized that owning just a fraction of one is enhancing.

Thus have crypto creators stormed the barricades, and thus is crypto art a certifiably new paradigm. As art history teaches, after each revolution – perspective, impressionism, cubism, abstract expressionism – the toothpaste, as went the saying, could not be put back in the tube. So, whether you sign on to cryptomania as collecting, investing, or gambling, as with every new paradigm, attention must be paid.