by NATASHA KURCHANOVA

An elegant exhibition of the works of Alexey Titarenko (b1962, Leningrad) at the Nailya Alexander Gallery in New York is a rare glimpse into the vision of an artist who attempts to capture a change of worlds and histories while preserving the integrity of personal vision. Composed of about two dozen images from various stages of the artist’s career, the exhibition guides us through four cities in different parts of the world – St Petersburg, Venice, Havana and New York – that left a stamp on Titarenko’s life, but also made him see these cities in a distinctive way.

Alexey Titarenko. From the series Nomenclature of Signs (Meat, Fish), 1986-1991. Unique gelatin silver photomontage, 13 ½ x 14 in (34.3 x 35.6 cm).

Using black-and-white photography and long exposure, Titarenko outlines the contours of his vision as fragments of reality that is long gone, sparsely populated and somewhat melancholic, but believable nevertheless. Like a dream that fills us with a conviction of the specialness of a moment that holds a singular truth, each image in this exhibition conveys the certainty that the moment captured in it is real. The title of the exhibition, The City Is a Novel, imparts the sense of the special nature of this reality as something that can not only be read and interpreted, but also felt. Titarenko spoke to Studio International after the exhibition had opened.

Natasha Kurchanova: When I saw your most recent book, which, like the exhibition, is called The City Is a Novel,1 I noticed that its title creates a parallel between literature and photography. Your text also traces the same parallel, as well as comparing photography and music. Could you talk more about photography as it relates to literature and music?

Alexey Titarenko: Any person has a connection to literature. Literature is like photography, because it is black and white. It may be a playful comparison, but there is a grain of truth in it. In literature, the black-and-white signs did not carry any iconic representation all by themselves, but they helped me to develop my imagination. The more I read, the more my imagination developed and formed the basis of my creativity. When I was a boy, I walked along the city streets, and some things around me – such as buildings, their architectural details and smells – elicited feelings of delight, euphoria, emotional excitement and inspiration. They were responsible for creating a special state in my soul. Because I was little and did not know better, I associated this state with the city and with the things that I saw around me. When I was given a camera at eight years of age, I said to myself that it was precisely the kind of instrument I could use to help me preserve these fleeting moments of the condition of my soul. I could make them last longer, and return to them over and over again. I took my camera and went to after-school photography classes for children at the Kirov Palace of Culture on Vasilyevsky Island, St Petersburg and, little by little, I learned to use it. It was a rather primitive piece of equipment. The problem was also that the pictures I made with it did not evoke any inspiration in me. The only feeling they evoked was that of deep dissatisfaction, or even boredom.

Alexey Titarenko. Black Cats, St. Petersburg, 1997. Gelatin silver print, printed by the artist, edition 1/15, 12 x 12 in (30.5 x 30.5 cm).

NK: What did you do then?

AT: When nothing happened with my first photographic experiments, I lost interest in photography and went back to literature. I developed a very fast reading style and, in a relatively short period, read many books. At the time, several children’s libraries in Leningrad had books that were impossible to find in adult libraries – by Stefan Zweig, Thomas Mann, the Strugatsky brothers, for example – because the children’s libraries had priority in ordering books that were in scarce supply elsewhere in the Soviet Union. Children’s libraries served those under the age of 14. So, by 14, I had read all of Dostoevsky, Mann, Zweig, and many other great authors.

NK: Where was the library you used?

AT: It was in the Kirov Palace of Culture, where I went to photography classes. The Palace of Culture was a huge building, a masterpiece of Soviet constructivism created by architect Noy Abramovich Trotsky, that could accommodate multiple organisations and institutions. It had beautiful big auditoriums and lecture halls that could be rented out and used to seat large numbers of people. It had several floors, each with a separate movie theatre, which meant that several films could be shown there at the same time. Later, when I studied film production at the Leningrad Institute of Culture [now the St. Petersburg State University of Culture and Arts], we were taken to this cinema for so-called “closed séances” that were not open to the general public, where they showed us films by Akira Kurosawa and American directors. It was a perfect place for professors and students from the Institute of Culture because several films could be shown simultaneously to students taking various classes.

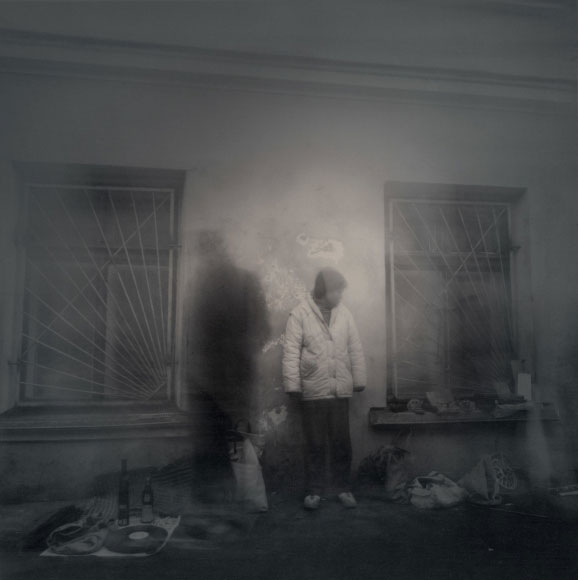

Alexey Titarenko. Man and Shadow, St. Petersburg, 1994. Vintage gelatin silver print, printed by the artist, edition 1/10, 12 x 12 in (30.5 x 30.5 cm).

NK: Could you tell me a more about this cinema?

AT: This cinema with its multiple movie theatres belonged to Gosfilmofond, the state film archive of the Soviet Union. It was a unique place, not least because it was one of only two cinemas in the entire country where you could see rare films. Only one copy of such films was received by the Soviet Union for its archives, but they were not shown widely. However, they were shown at the Gosfilmofond cinemas on a monthly basis in live translation. Live translation means that the film was shown in its native language, but translated by an interpreter during the screening. The Gosfilmofond cinemas were unique establishments, where you could see the original, non-censored version of Wild Strawberries by Ingmar Bergman, for example, as well as the so-called “trophy films”, such as Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, which were captured as trophies by the Soviet Army after the war with Germany. Other films were by famous western directors such as Pier Paolo Pasolini, Werner Herzog, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Akira Kurosawa, French auteurs, American directors and others. All of this attracted a great number of people, including me. Apart from reading all the “subversive” books, I was also watching subversive films, because I was under 14 and for me the ticket cost just five kopeks. Reading these books and watching these films changed my view of the world completely. Unfortunately, my photography could not live up to my aspirations at that time. No matter how much I tried to convey my feeling and perception of the world, I could not succeed.

Alexey Titarenko. Sunrays, St. Petersburg, 1995. Vintage gelatin silver print, printed by the artist, edition 3/10, 11 3/8 x 11 3/8 in (28.9 x 28.9 cm).

NK: Obviously, you did not give up photography after this initial dissatisfaction. What was your next step in your development as an artist?

AT: The education at the children’s photo studio allowed me to overcome all the technical difficulties and control the camera to the extent that, in theory, I could make things that I envisioned. This pushed me to look for ways to overcome my dissatisfaction and find the means to allow me to capture my inner perception of the world around me. When my attempts failed, I bought a more advanced camera and developed my technical skills further.

When I was 14, I also entered the faculty of Photo Correspondents at the People’s University of Social Professions, where I had very good teachers. This, too, was located in the Kirov Palace of Culture. This was a unique place in the city where I could be trained as a photographic correspondent. I took classes with Ilya Narovliansky, a very good correspondent from Leningradskaya Pravda, and other more pictorially oriented artistic photographers. I studied at high school at the same time as I took classes at the People’s University. At university, I attended lectures with perhaps 50 other people, mostly men. Once a week, I noticed that there was a strong smell of tobacco smoke in the hallways of the Kirov Palace of Culture. One night after class, I followed the smell and at one end of a long hallway found a room with a group of bearded men who were drinking vodka and talking about photography. On the walls, I saw a series of photomontages with a clearly marked anti-Soviet subject matter, such as tramps, people who were collecting bottles to make money, and old women selling clothes. I liked these images enough to stay, even though I was not a smoker and had to tolerate the tobacco-filled atmosphere. This gathering of bearded men turned out to be an amateur photo club called Zerkalo [meaning Mirror]. It was founded in 1977 by the same people who founded a jazz club called Kvadrat [Square]. The authorities did not pay much attention to its existence, especially because it was a time of the international détente. I asked the men if I could come to their gatherings, and they agreed. This was in early 1978. I studied at the People’s University for a year. After receiving my diploma, I brought to Zerkalo my own series of photo collages, based on the ones I saw on display there. There were about 12 of them, made out of shreds of my old photographs and glued together in a Dada-like manner. This was my official application to membership of Zerkalo. To my surprise, they accepted me. I was young – 15 years old at the time. After that, I became an active member of the club. Dropping straight photography and beginning to make collages was a welcome development, since it kept up my interest in working with this medium.

Alexey Titarenko. Gondolas, Venice, 2001. Gelatin silver print, printed by the artist, edition 5/10, 16 x 17 in (40.6 x 43.2 cm).

NK: Did you have any run-ins with authorities over your art?

AT: A year later, in 1979, I received my high-school diploma and applied to the Leningrad Institute of Culture. I enrolled there as a student in the department of cinematic and photographic art in August 1979. I was 16, and my political reputation was unmarred at that time. When I was accepted at the Institute of Culture, I was recruited to work as a guide at the Summer Olympic Games, which were to be held in the USSR the following year, 1980. As a result of my education in a school that emphasised French language and culture, I spoke French well. This was an assignment, rather than an invitation: it came from official governmental channels and I could not refuse it. I studied at the institute from 8am until 6pm, then, after that, I took classes for guides at Intourist [the official state travel agency of the Soviet Union].

Alexey Titarenko. From the series Nomenclature of Signs (statue with numbers), 1986-1991. Unique gelatin silver photomontage, 13 ¼ x 13 ½ in (33.7 x 34.3 cm).

It was a missed year for me as an artist, although my collages were hanging in the photo club all this time. In a way, I lost control over them and could not prevent an unpleasant incident. Without notifying me, the club sent my works to a travelling exhibition in the Baltic republics and Finland. In June 1980, my works were seized at the Finnish border by Soviet border guards, who opened the box with my collages and launched an investigation. They learned everything about me, including the fact that I was a member of Zerkalo. At the Institute, I was called to the dean’s office and told that, because I already had a group of foreign tourists assigned to me, it was too late to expel me, but that if anything like this happened again, I would be expelled. Shortly before this, in May 1980, the KGB took an interest in the photo club, not necessarily because of my photomontages, which were rather innocuous, but because of those by Gennadii Tkalich, who made beautiful photomontages in the style of John Heartfield on subjects such as old babushkas dragging a pile of empty bottles to а recycling facility, shown against the background of a grey, menacing sky. After an exhibition of photographs including Tkalich’s images opened at Zerkalo, Tkalich was tried and jailed for 10 years for creating anti-Soviet images. Zerkalo was closed after these two related incidents.

Alexey Titarenko. Woman in Doorway, Havana, 2003. Gelatin silver print, printed by the artist, edition 1/5, 10 3/4 x 10 7/8 in (27.3 x 27.6 cm).

NK: Where were the offending images exhibited?

AT: At the Kirov Palace of Culture, where we opened an exhibition space for showing photographs. It was the first exhibition space of its kind in the city. It was located just to the left of the entrance to the Gosfilmofond cinema. Usually, Zerkalo’s exhibitions in that space did not attract much attention. However, there was one retiree who complained to the KGB division in St Petersburg, the central committee of the Communist party in Moscow, and other official channels about anti-Soviet photographs being displayed at the new exhibition space. Because of this complaint, an investigative committee was formed, which arrived early one morning, before the exhibition opened to the public. They opened the door, took all the photographs out of their frames quite unceremoniously, breaking the glass in the process.

NK: When did this happen?

AT: In June 1980, around the same time that my photographs were seized at the Finnish border. I do not think the authorities would have taken an interest in this exhibition were it not for the anonymous complaint, which they had to answer. During this period, from 1980 to 1983, I decided to concentrate on my studies. I had to make four films to fulfil my institute curriculum; we had classes from 8am to 6pm. I also had to work, because my parents would not give me money, and my student stipend was only 39 roubles a month. I found a job as assistant to the administrator in the Large Hall of St Petersburg Philharmonic. I went to work there at 6.30 every night, because I loved music and this job gave me the opportunity to listen to it for nothing. During my employment at the Philharmonic, I listened to almost 900 concerts.

Alexey Titarenko. Bell Tower, Venice, 2006. Gelatin silver print, printed by the artist, edition 5/10, 11 3/4 x 11 3/4 in (29.8 x 29.8 cm).

NK: Russia has obligatory military service for men. Where you ever enlisted in the army?

AT: I was meant to serve in the army when I turned 18, but my recruitment was adjourned until the second half of 1983, when I finished my studies at the Institute of Culture. It was the time of the Soviet war in Afghanistan. After more than a year of service as an infantry soldier, the KGB arrested me because some conscripts, with whom I was friendly, had told the authorities that I was spreading anti-Soviet propaganda. This story could have ended rather badly, but luckily for me, the KGB decided not to bother with formalities – as they were sure of the total impunity of their actions – and put me in a prison cell without a formal arrest warrant. It is complicated to explain a rather chaotic function of Soviet military but, at one point, when all the chief commanders of the army were away on manoeuvres and an officer on duty was new and unaware of unwritten rules, I was lucky to get the opportunity not only to be released, but also to be discharged from my military duties, because I had served my obligatory 18 months, and the arrest was not on the record, as there was no arrest, legally speaking. However, the fact that I was discharged without an official letter stating my good behaviour made it impossible for me to find employment in my profession.

After the army, I joined a geological expedition in the northern forest. My job was to develop overnight special films with images and data taken by the expedition’s plane in the research area during the day. When this expedition found uranium, we were given a generous bonus, and I made a lot of money. At the end of 1985, when I returned from this expedition, this allowed me to buy a very good camera and begin making art seriously. I went back to Zerkalo, which had reopened in a different, less conspicuous, location.

Alexey Titarenko. Palm Tree, Havana, 2003. Gelatin silver print, printed by the artist, edition 3/10, 16 x 16 in (40.6 x 40.6 cm).

NK: Are some of the photographs in this exhibition at the Nailya Alexander Gallery from that first series, which you took with your new camera?

AT: Yes, this series is called Nomenclature of Signs. It dates to about 1986. I cannot give a more precise date, because these images were not created in one sitting. Each work comprises an entire process. First, I took pictures and created negatives. Then I put them together like a sandwich and considered different possibilities of combining images. The first photographic collages or superimposed works were made in 1986. I was fortunate at that time to find a dark room. I had a friend, a photographer named Boris Smelov, who had many friends among artists and poets. One of these friends, a poet called Victor Sokolov, became the head of a student club at the Polytechnic Institute. Because I needed a dark room, Victor invited me to teach photography in his student club. The position did not pay well but, as well as the dark room, it also gave me the status of a working person, not a social parasite.

NK: Are all the pictures in this exhibition collages?

AT: These are superimpositions of several negatives. I also made collages, but they are not in this exhibition. Some of them are published in my book. After I superimpose the negative, I go in and touch up the image with a brush. Any brown in the image is a sign of me using the brush to colour the print with sepia. As a result, silver was oxidized and turned into silver sulfide, which is brown in colour. This series of superimpositions of several negatives is two-coloured, gray-yellowish. In 1986-87, I also made collages out of newspaper pieces, red bunting and fragments of photographs. I glued all that on to pieces of cardboard painted with black matte gouache. I did not care much about their precise dates, because I was doing these works to escape Soviet reality, not to make history. I began walking around the city and taking pictures about the city for the Nomenclature of Signs series in 1986. I wanted to make a series of collages, photomontages and superimpositions about St Petersburg. In 1989, the Aperture Foundation in Paris and the US exhibited this series. Two of my collages were illustrated in its catalogue.

Alexey Titarenko. 58th Street, New York, 2012. Gelatin silver print, printed by the artist, edition 4/10, 12 1/4 x 12 1/4 in (31.1 x 31.1 cm).

NK: Nomenclature of Signs confronts the iconography of the Soviet Union. Did your subject matter change after the fall of the regime?

АТ: I explained it in the book; it is difficult to describe this in words. Nomenclature of Signs was a product of its time, of my own personal vision and thinking about what was going on around me. Not straightforwardly, of course, but with the help of metaphor. When the Soviet Union began collapsing, then everything changed, of course, including the way I was making art. The basis of my world changed, and my art had to change as well. I finished using Soviet symbolism with the fall of the Soviet Union. Literature helped me put an end to this last Soviet series in my work. I wrote a story called The Nomenclature of Signs. It is on my website, in Russian and English. This story marked the finish mark of the series. It mentions the fact that an epoch was ending.

Alexey Titarenko. Corner La Esquina, New York, 2013. Gelatin silver print, printed by the artist, edition 1/5, 12 x 12 in (30.5 x 30.5 cm).

In 1989, Leningrad experienced the first signs of food shortages. First, it was sugar. At that time, every region was fending for itself. In the 90s, food coupons were introduced. That’s when hunger started. In 1991, it became worse. The stores were empty. It was difficult to buy basic food, such as pasta, for example. Bread, however, was available, although one had to stand in a long line to buy it. It was the time when Leningrad was renamed St Petersburg, and when Anatoly Sobchak became the mayor of the city. Why there was such shortage of products, no one knew. Thinking back, it looks as if the KGB were preparing a putsch and all the products were simply hidden, so that people would become dissatisfied. Officially, it was explained by the fact that, during a time of freedom and democracy, people start stealing things. The city took the situation seriously and decided to sell precious metals, oil, wood and other raw materials abroad, so that it could buy food and crucial medical supplies, such as insulin, for its population. Sobchak asked his department of external affairs to conduct this sale. Vladimir Putin was then the head of this department. What I read in the press at that time and was told by, for example, former member of the city council Marina Sallier, was that Putin signed agreements with people who were known criminals and with whom he allegedly (I was told) had good relations from his time as а KGB operative. People who were familiar with the situation said that he sold these raw materials at 15% of their value. And those millions of dollars of revenues that he received from the sale subsequently disappeared. Putin was suspended briefly from his position and а criminal case was opened against him. However, he was not fired and was never found guilty of anything. The general attorney’s office disappeared with disappearance of the Soviet Union. Sobchak continued to deal with the sale of goods, but there was still such scarcity that there was nothing that could be sold. The city was starving. Then I understood how ridiculous it was to continue making art criticising the Soviet Union, which no longer existed, when people were dying of hunger.

Alexey Titarenko. Morningside Park, New York, 2015. Gelatin silver print, printed by the artist, edition 7/10, 17 x 17 in (43.2 x 43.2 cm).

At the time, people in St Petersburg were dressed in black or grey. After work, they spent their time running from store to store trying to find provisions and buy something with their coupons. Electricity was limited – there was little or no lighting at night. This impression of St Petersburg at that time reminded me of a scene in Virgil’s Aeneid, when Aeneas descends into the Kingdom of Shadows in search of his beloved, and there he meets the shadows. At that time, I decided that I should return to the 19th-century technique of a long-exposure shot to convey my condition through the metaphor of the shadows. One day, I was walking to the Vasileostrovskaya metro station in my neighbourhood when I saw a sea of people crowded near the entrance. The metro was the only means of transport at the time, because there was a shortage of fuel in the city, and buses and cars did not operate. This was the only metro station on Vasilyevsky Island, a heavily industrialised and populated district of the city.

NK: There was no Primorskaya metro station at that time?

AT: I do not think Primorskaya station was open then. Even if it was, all the factories were near Vasileostrovskaya station. All these masses of workers were trying to get into the metro, which was impossible, because the escalators did not work. People were allowed into the station in small groups. This created an apocalyptic situation because, when you entered this mass, you could not leave it. You were sucked into the crowd and either pressed forward or cast outside. There were people who reached the only available escalator without their shoes or other articles of clothing, which were lost or stripped from them along the way.

Alexey Titarenko. Vasileostrovskaya Metro Station (Variant Crowd 2), 1992. Gelatin silver print, printed by the artist, edition 15/15, 12 x 12 in (30.5 x 30.5 cm).

In this photograph (Vasileostrovskaya Metro Station (Variant Crowd 2) from 1992, you can see someone’s shoe that was cast out in the stampede. My other photographs captured broken crutches, because when people fell, they could not get up and others had to step over them. In photographs with a long exposure, you cannot see anything that moves fast. You can see the difference in the quality of movement in some images: in this part of the crowd, people moved faster, but in this slower, so it is a bit more distinct. What looks like an empty space in the picture is just the slowing of the Brownian motion of the crowd reaching its destination. To make this photograph, I positioned my camera next to a closed door with no people in front and opened the shutter. I left the scene so that people would not notice that I was photographing them. I closed the shutter in two minutes. Then I went home, developed the film, and saw that the result conveyed my feeling, my perception of the event. I finally achieved the goal of capturing on film my inner impressions. This image was a breakthrough, not only because it allowed me to achieve my lifetime goal of expressing my inner state in an image, but also because I understood that I had done the right thing socially. Had I not captured that moment of history, it would have remained forgotten.

NK: Was this photograph taken in 1991?

AT: No, in 1992. I began taking pictures like this in November and December 1991. I have thousands of negatives like this and about 40 pictures.

NK: It looks as if this exhibition contains the images made in the mid-80s and early-90s as far as St Petersburg is concerned?

AT: Yes, but there are also a few images from the series The Black and White Magic of St Petersburg from 1995-97. It was when everything calmed down and the new constitution was accepted.

Alexey Titarenko. Crowd 1, St. Petersburg, 1992. Gelatin silver print, printed by the artist, edition 1/5 AP, 17 x 17 in (43.2 x 43.2 cm).

NK: What about the images of Venice and Havana – when were they made?

AT: After 2000.

NK: Why did you decide to photograph these two cities besides St Petersburg?

AT: I photographed Venice because St Petersburg is often called “the Venice of the north”. The only major difference is that St Petersburg is an unhappy city, with much suffering going on. Venice, on the contrary, is a happy place.

NK: What about Havana?

AT: Havana, like St Petersburg, is also a time machine. It brings you back to the time of the attempt at building a communist society. In my images, I decided not to pay attention to the social and political aspects of this endeavour, but rather to focus my attention on conveying my impression about the everyday life of people I met on the streets. In 2011, my Havana pictures were exhibited at the Getty Museum as part of the exhibition A Revolutionary Project: Cuba from Walker Evans to Now. I do not know why they chose my images, but I think they may have caught a similarity between my images of Havana and the way Walker Evans captured this city in the 1930s. They may have wanted to show the continuity in the vision of Havana in the works of photographers from different countries and generations. Like Evans, I did not focus on the political aspects of the Cuban situation. Like him, I made black-and-white images with a medium-sized camera. The exhibition also contained political pictures of Cuban photographers from the 50s, 60s and 70s and contemporary colour photography documenting the life on the revolutionary island.

NK: I also see the images of New York in this space at Nailya Alexander.

AT: The New York images are very recent, starting from 2010. I first came to this city in 2000, and visited it perhaps 30 times before receiving permanent residence here in 2008. After all I lived through, for me New York is a happy city. Sometimes I have nostalgic feelings about other places, and I am trying to convey them metaphorically in my images.

Reference

1. The City Is a Novel by Alexey Titarenko is published by Damiani, 2015.

• Alexey Titarenko: The City Is a Novel is at the Nailya Alexander Gallery, New York, until 20 May 2017.