by ANNA McNAY

Born in Brooklyn in 1927 to Russian parents, Alex Katz entered the prestigious Cooper Union Art School in Manhattan in 1946, where he was taught to paint from drawings, and exposed largely to modern art. Throughout the period of abstract expressionism, Katz remained a staunch figurative painter, spending his summers in Maine, where he made landscapes en plein air. In the early 60s, influenced by film, television and advertising, he began painting large-scale works, with dramatically cropped faces. His work is often described as “very American”, but Katz seemingly has no agenda. His motivation is to capture what he sees before him, be it landscape, cityscape, or portrait, and, unlike many artists, he doesn’t hanker after timelessness or immortality, recognising, rather, that time keeps moving and reality doesn’t exist beyond what he terms the “immediate presence”.

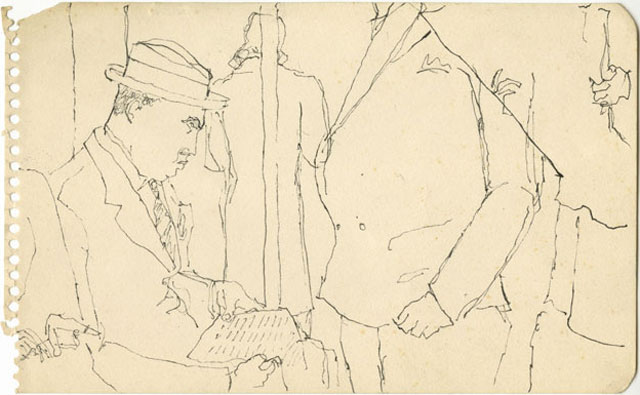

Alex Katz. Man with Newspaper on the Subway, c1940s. Black ink, 4 7/8 x 7 7/8 in. © Alex Katz / DACS, London / VAGA, New York. Courtesy Timothy Taylor 16×34.

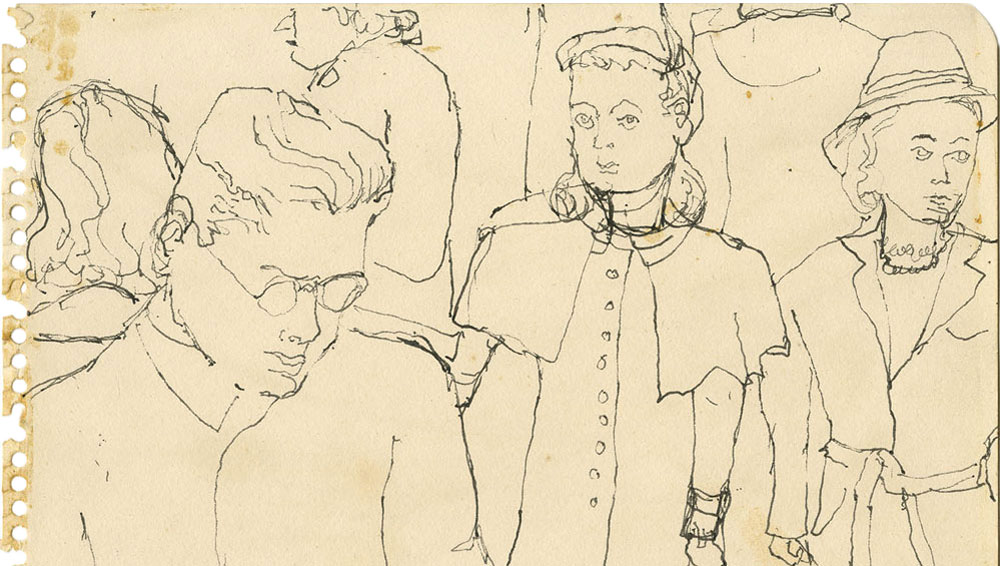

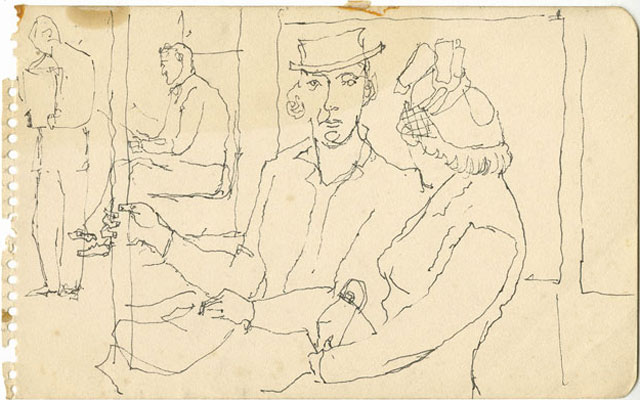

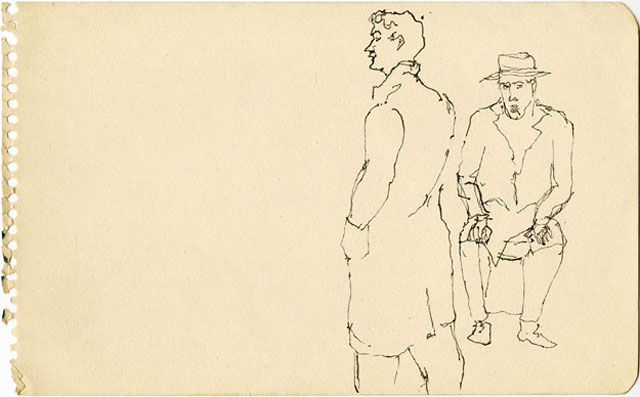

For Katz’s latest exhibition in London, gallerist Timothy Taylor has chosen to bring out some very early pencil and ink drawings made by the artist on the New York subway during his student days and to show these alongside recent landscape paintings and sculptures. Studio International met with Katz in the Mayfair gallery, ahead of the exhibition opening.

Anna McNay: The starting point for this exhibition is a series of drawings you made on the New York subway when you were a student at the Cooper Union Art School.

Alex Katz: I was trying to learn how to draw so I could stay in school and not get thrown out, so I started drawing whatever was in front of me, on the subway, going to school, coming back – I just kept drawing for about three years. I learned to draw quickly, between stops, maybe working for 10 minutes or so.

Alex Katz. Subway Scene Couple, c1940s. Black ink, 4 7/8 x 8 in. © Alex Katz / DACS, London / VAGA, New York. Courtesy Timothy Taylor 16×34.

AMc: Were you using ink?

AK: At first I was working with pencil, but then it went to ink.

AMc: You didn’t intend to show those drawings when you made them, did you?

AK: No, they were never shown. Then Timothy [Taylor] got this small gallery in Chelsea [New York] and I said, “You know, those drawings would look good there”, and he thought it was a good idea.

AMc: Presumably, these were all pages in sketchbooks, which you have torn out for the exhibitions?

AK: Yes.

AMc: When they were shown earlier this year in New York, they were shown alone, just the drawings by themselves, but for this show in London there are also paintings and sculptures. How did that evolve?

AK: It was Timothy’s idea. It’s his show. I didn’t choose anything. The paintings are from a couple of years ago, but they were somehow never shown before.

,-2017.jpg)

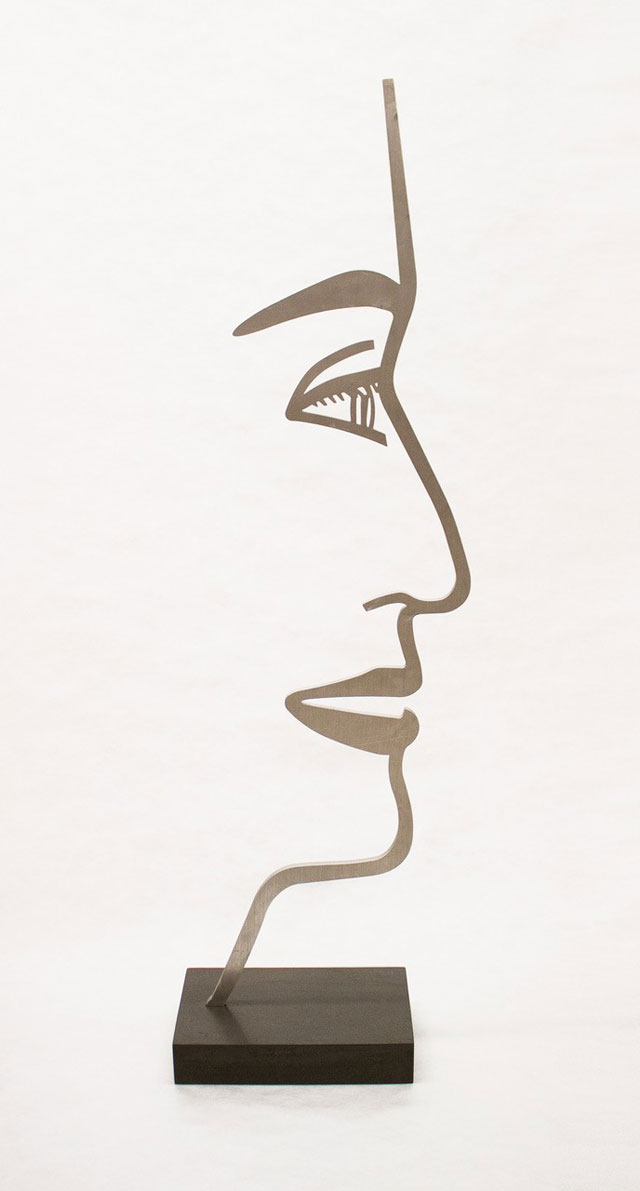

Alex Katz. Departure (cut-out), 2017. Archival inks on shaped powder-coated aluminium on white bronze base, 56 x 22 x 6 cm. © Alex Katz / DACS, London / VAGA, New York. Courtesy Timothy Taylor 16×34.

AMc: Are they all from Maine, where you spend your summers painting?

AK: Not really. Most of my big paintings – about 90% of them – are from Maine, yes, but one of these is from Pennsylvania and one is from New York City. We have a place in Pennsylvania that my wife and son use a lot for the weekends.

AMc: You also have a place in Maine, where you have been going every year since 1949, when you spent two summers at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and later bought a house in Lincolnville.

AK: Yes, we bought the small house in 1954 and have been going there ever since.

Alex Katz. Two Men, c1940s. Black ink, 8 x 5 in. © Alex Katz / DACS, London / VAGA, New York. Courtesy Timothy Taylor 16×34.

AMc: What is it particularly about the place that keeps taking you back?

AK: It has great light. It’s softer, and most of the colours are richer, that’s one reason. But also painting in Maine is like being a carpenter, it’s an accepted vocation. In Queen’s, where I grew up, when I put an easel out in the street, people would say: “Oh, that’s crazy! Look at him, he’s at it again.” Whereas, in Maine, I ran into a plumber who I hadn’t seen for 20-odd years and he said, “Hey, are you still painting?” and I said: “I like to keep my hand in.”

AMc: You work en plein air with your easel and palette. Do you make sketches first?

AK: I make small paintings first and then I make larger ones later.

AMc: Do you use photography at all?

AK: Now I do, I’m using my iPhone. But I can’t get the light and the colour right with that, so I have to back it up with actual painting. I started with the iPhone about two or three years ago. With the iPhone, I can capture more gestures in a shorter period of time than I can with drawing, so I get gestures that I would otherwise never get.

AMc: How much of a part of your practice is drawing still?

AK: Oh, I spend most of my time drawing. I spend far more time doing that than the larger paintings. It’s about getting the drawing and the logic right. Once you transfer that to the canvas for the painting, what you see is what’s there. My technique is wet paint into wet paint, so my paintings are not worked over.

AMc: Do you still work with ink or pencil sometimes, too, or do you just “draw” with paint?

AK: If I’m not sure about something, I’ll sometimes go back and make an ink drawing.

AMc: When you look back at the subway drawings now, do they take you back to when you were making them? Do you remember specific instances and scenarios?

AK: I remember meeting a pretty girl at four in the morning on a train coming from New York to Queen’s. We had a conversation, but she got off before I got her phone number and I remember that to this day – regrettably!

AMc: When you’re making quick sketches like that, what is it that you’re trying to capture? Is it a physical likeness?

AK: No, it’s basically the sensation of what you see. Translating what you see on to the canvas. It’s not naturalistic or literal. You’re trying to get the equivalent of the sensation in translation.

Alex Katz. ADA, 2017. Polished stainless steel, absolute granite base, 11 ft. © Alex Katz / DACS, London / VAGA, New York. Courtesy Timothy Taylor 16×34.

AMc: You’ve been making sculpture, too, since 1959, when you began working with plywood. The single-line sculpture inspired by your wife, Ada, included in this exhibition, really towers over everything and everyone.

AK: I could see it in my mind how I wanted it, and I got a big piece of paper and kept changing the size of it. It didn’t make any sense at six foot, but by the time it got up to ten-and-a-half foot, it made sense.

AMc: You said very early on that the reason you made your paintings so big was a wish to stand up to the abstract expressionists and create something figurative that would, to quote you, “knock them off the wall”. Is there still a competitive element to your work?

AK: Yes, definitely. On the one side, I’m competing with the kids, who are now making painting, and I’m also still competing with the old guys.

AMc: Is that part of what drives you?

AK: When you’re painting, all you’re thinking about is painting, the canvas and what you’re putting on to it. But you have to have something that makes you go, yes.

Alex Katz. Two Trees, 2015, Oil on linen, 120 x 96 in. © Alex Katz / DACS, London / VAGA, New York. Courtesy Timothy Taylor 16×34.

AMc: You’ve said before that painting should be shown on its own, not in a “food show”, where you walk by taking samples.

AK: Yes, painting should be shown with other painting. If it’s shown with mixed media, it becomes a little difficult.

AMc: How do you feel about showing drawings and sculptures side by side in this exhibition? Is it different, when it is all your own work?

AK: Yes, that’s OK. And it can be shown in museum shows alongside other people’s paintings. That’s OK, too.

AMc: Has your style changed much over the years?

AK: The basic premise of what I do has changed very little, but the solutions have changed. No solution in painting is valid after a while; it becomes obsolete. In my own mind, if I can’t get it right, it keeps changing.

AMc: What sort of things have you changed?

AK: In 1959, I was working with flat backgrounds. I’m working much more baroque now. My tastes have changed.

AMc: Do you look at much art by other artists – for inspiration, maybe?

AK: I like looking at art. You’re always looking and learning and changing your perception about things.

AMc: When you are composing a painting, you have mentioned before about the “grammar” of a painting being abstract.

AK: The grammar of a painting is always abstract.

AMc: You have never painted something that you would call abstract in itself though.

AK: No, I don’t paint abstract.

AMc: At the same time, you don’t agree with the concept of subject matter.

AK: Subject matter is inspiration.

AMc: And what would you say is the subject of a painting?

AK: The subject is style – line, colour, how the whole thing is put together. Ultimately, content is not important. The style is what is important.

AMc: Where does the idea for a new painting come from?

AK: It just comes out of the sky. The unconscious puts it there and you just follow it.

AMc: Do you know what the finished work will look like when you set out?

AK: No. You look at it at a certain point and say: “Why am I working on this?” In the preparatory stages, you have some idea and then when you’re painting you have to keep asking yourself what you like about it and what you don’t like about it and how you can make it better. And you have to make those decisions quickly.

AMc: Do you ever destroy paintings?

AK: Not any more. When I was learning how to paint, I destroyed maybe 1,000 paintings. But what happened was I learned how to paint.

AMc: So, now you always find a way to make it work?

AK: More or less.

AMc: Can you say something about the idea of the “immediate presence”, which is key to your work?

AK: That’s why I get a lot of trouble with my paintings, because I’m telling you, “This is what it looks like” and I’m telling you, “This is what a good painting is”, and it’s a rejection of a lot of modern art. It makes a lot of people insecure and unhappy. When people say such things as, “A great work of art is a joy for ever”, I say, “Well, there is no for ever”. “For ever” is absolutely fixed in time and I don’t believe in that. Everything is moving. There’s no reality, it’s moving. Reality is subject to fashion and so you get something where there’s no past tense, there’s no future tense, there’s only now. And I want to paint the now. That’s the immediate presence. And that’s what consciousness is. Our lives are subject to fashion and the fashion industry tries to hook on to this. It’s the same for painting, writing, music and clothes. Everything is subject to fashion. My paintings are not narrative. Narrative is time. If you strip a painting of narrative, it’s just an image, and if that image has enough energy, it will get you where you want to go.

AMc: In your portraits, the clothes, the bathing suits, the hats – they are all markers of the fashions of their time.

AK: Yes, everything is of its time. You paint what is in front of you.

AMc: You are not worried that this will date you?

AK: No, not at all. A lot of people want to paint something timeless, but I paint the immediate presence.

• Alex Katz runs until 18 November at Timothy Taylor, London.