Ai Weiwei, Han Dynasty Urn with Coca-Cola Logo, 2014. Courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio.

Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge

12 February – 19 June 2022

by BETH WILLIAMSON

Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge might seem like a small venue for a solo exhibition of work by the renowned Chinese artist Ai Weiwei (b1957), yet this new exhibition, The Liberty of Doubt, juxtaposes artworks and ideas in a way that achieves as much as any blockbuster – it is distilled and powerful. As the exhibition’s title suggests, Ai Weiwei here explores the liberty of doubt, the freedom to express doubt in political matters, and there is a stark contrast between the situation in the west and authoritarian regimes like that in China. In a recent interview, the artist said: “Liberty of doubt is … a prerequisite for culture and ideological development. Without this spirit, as happened in some historical eras, it would be like a pool of stagnant water, from which corruption would emerge.” These are the sorts of ideas we expect Ai Weiwei to explore, but he goes further. The exhibition also explores related questions of truth, authenticity and value. This is where thing get interesting as we see, for the first time, artworks by Ai Weiwei exhibited alongside historic Chinese items bought by him at auction in Cambridge in 2020.

A Chinese Lacquered Greystone fragmentary hand clutching a vase. Courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio.

The historic pieces are thought to date from different periods in Chinese history – the Northern Wei (386-534CE) and Tang (618-907CE) dynasties – and some are identified as counterfeit copies. Whatever their condition, authentic or fake, their value in this exhibition is surely in their juxtaposition with Ai Weiwei’s contemporary works, creating a space for thinking about the ancient and the contemporary, aesthetically, politically, socially and economically.

,-2017.jpg)

Ai Weiwei, Dragon Vase, 2017. Courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio.

The contrast of the modern and the traditional is marked in the two main gallery spaces where ideas of value and authenticity are explored at large. These ideas are investigated through the display of historic items subsequently identified as fakes or originals. They are also interrogated through Ai Weiwei’s own work, such as Han Dynasty Urn with Coca-Cola Logo (2014) or Dragon Vase (2017).

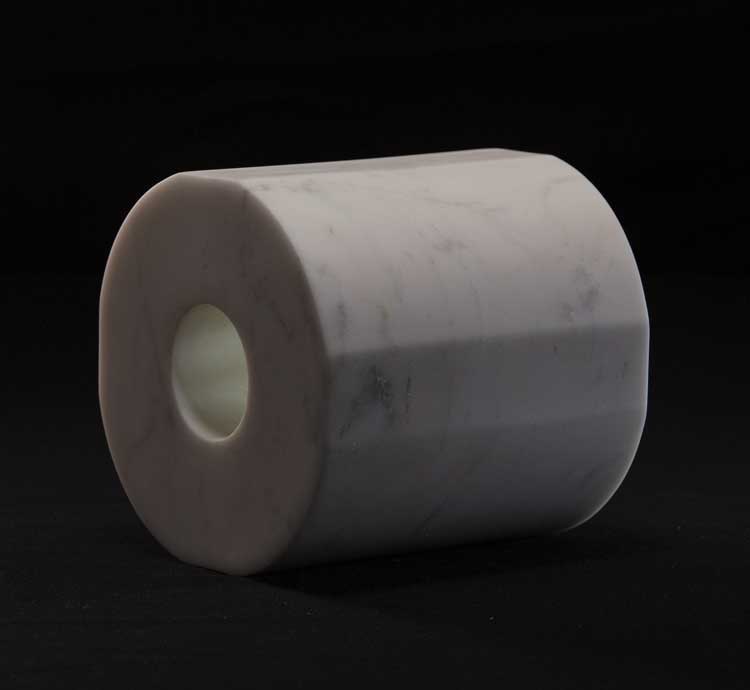

Ai Weiwei, Marble Takeout Container, 2015. Courtesy Ai Weiwei studio.

Meanwhile, other works raise questions relating to globalisation and the pandemic. The ubiquitous takeaway box becomes enshrined in Marble Takeout Box (2015) and the panic-buying of toilet rolls at the start of the pandemic emerges in Marble Toilet Paper (2020). Why we revere certain objects and not others is an important point for Ai Weiwei and such ideas, serious and playful, come up in objects such as iPhone Cutout (2015). Craftsmanship is important too. In a question-and-answer session with the Kettle’s Yard director, Andrew Nairne, Ai Weiwei explained how his work Handcuffs (2011), carved from a single piece of fine jade, was a technically challenging piece for craftsmen to make, testing their skills.

Installation views of Ai Weiwei: The Liberty of Doubt, Kettle’s Yard, February – June 2022. Photo: Jo Underhill.

It is, of course, more than just a technical challenge as it references his arrest and imprisonment in China for 81 days in 2011. The modern and the traditional are brought together again in Brain Inflation (2012), a large porcelain plate with an image of an MRI scan of Ai Weiwei’s brain following police violence when a cerebral haemorrhage required brain surgery. In another example, Cosmetics (2013), jade, a durable and valued material, is formed into the shape of disposable plastic cosmetics containers.

Ai Weiwei, Marble Toilet Paper, 2020. Courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio.

Returning to the idea of fake or original, wood and glass display cases fill one gallery space and house the artefacts Ai Weiwei bought at that auction in Cambridge in 2020. The display cases themselves, crafted in China, lend an air of value and authenticity to the objects they house, although only some of the objects are thought to be original while others are copies. Among those objects thought by Ai Weiwei to be originals are a Chinese red puddingstone crouched hare in Sui dynasty style and a Chinese limestone fragmentary torso of a Buddha in Northern Wei dynasty style. Among the objects thought to be copies made in the last 30 years is a Chinese veined marble seated figure of Laozi and a Chinese carved stone standing figure of Avalokiteshvara with aureole, both in Northern Wei dynasty style.

Installation views of Ai Weiwei: The Liberty of Doubt, Kettle’s Yard, February – June 2022. Photo: Jo Underhill.

The exhibition guide is very good at explaining the significance of each of the small sculptures in the exhibition and also provided a glossary of less familiar terms for the visitor. The sculptures, housed in display cases, fill the space and are set against the backdrop of Ai Weiwei’s Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (2015) made in Lego bricks. The artist’s deliberate destruction of the ancient urn, smashing it into tiny pieces, was captured in three photographs, mirrored here by the recreation of the photographic image in thousands of small Lego bricks. It is quite something to behold.

Installation views of Ai Weiwei: The Liberty of Doubt, Kettle’s Yard, February – June 2022. Photo: Jo Underhill.

The documentary films by Ai Weiwei shown upstairs at Kettle’s Yard are astonishing. Cockroach (2020), Coronation (2020) and Human Flow (2017) are shown on a rolling programme throughout the exhibition’s run, with two of the three films screened each day, one at 11.30am and the other at 2.30pm. These are substantial films and run to 93 minutes, 113 minutes and 145 minutes respectively, so allow plenty of time for viewing and plan ahead if you can. Human Flow is concerned with mass human migration and the refugee crisis, while Coronation is about the lockdown in Wuhan during the Covid-19 outbreak in spring 2020. Cockroach documents protests in Hong Kong during 2019 and it makes for challenging viewing. The protests were sparked by concerns for freedom when the Hong Kong government proposed a bill allowing criminal suspects in Hong Kong to be extradited to mainland China for trial. The protesters are passionate and police suppression and violence is intense. The crowds of clashing groups and constant noise add to the frenetic scenes.

Ai Weiwei, Surveillance Camera with Plinth, 2014. Courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio.

This is a political exhibition, but it is also intensely personal. It is a serious exhibition, but it is also playful. Ai Weiwei’s Surveillance Camera and Plinth (2014) perhaps encapsulated all these things. The artist’s studio in Beijing has been under constant surveillance since 2008. In this work, however, the camera is made of marble and mounted on a pedestal of ancient Chinese design. Similarly, his Finger (2015) wallpaper displays the middle finger gesture as an irreverent sign, indicating his position as a protester and playful provocateur. It is this repeated play of ideas – fake or original, ancient or modern, serious or playful – that makes Ai Weiwei’s work in this exhibition so powerful.