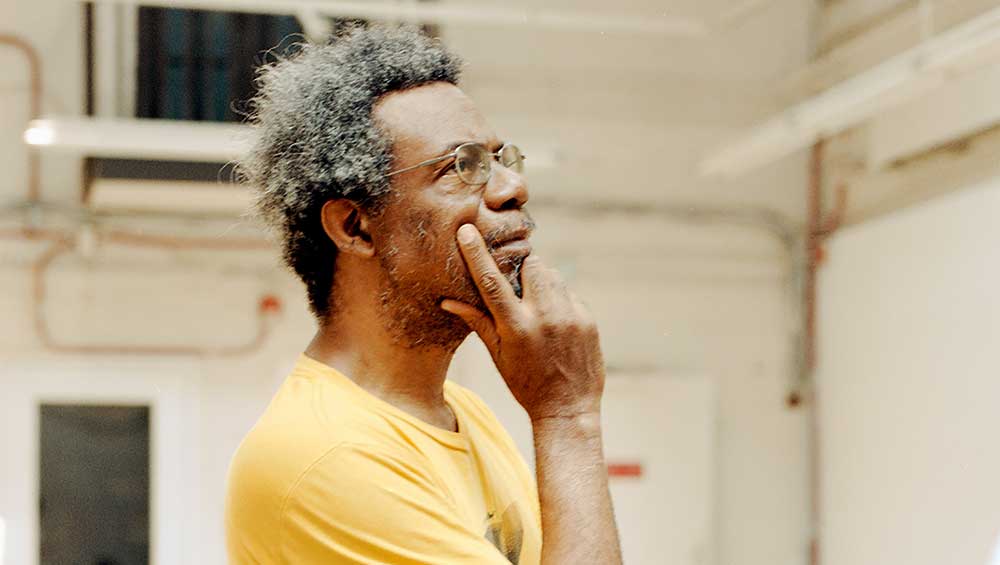

William Pope.L. Photo: Peyton Fulford.

by VERONICA SIMPSON

I didn’t know what to expect as I pushed my way through the red plastic “butcher’s shop” strips obscuring the South London Gallery’s traditional exhibition space. But collapsing timber towers, a soundtrack of sifting and creaking noises, trampled orange magnolias and leaking fluids that reeked of intoxication and sterilisation, added a unique atmosphere and texture to the exhibition, enhanced by the presence of the artist himself, William Pope.L. The toppling white, wooden structure in the main room led the Guardian to headline its review, “Sublime shipwreck misses its crawling captain”, which gained tragic weight four weeks later when the artist died suddenly, on 23 December 2023.

Installation view, William Pope.L: Hospital, South London Gallery, 21 November 2023 – 11 February 2024. Photo: Andy Stagg.

At the press preview in November, Pope.L conversed freely with the gallery’s director, Margot Heller, and attending journalists and critics. Dressed casually in layered chequered shirts over jeans with a felted-wool baseball cap covering his greying locks, he sipped coffee from a paper cup, relaxed and at ease. When Heller said he had once described himself as “the friendliest black artist in America”, he quipped: “That was a long time ago. I’m more bitter now. I’ve lost my sheen.”

This kind of dark, dry humour, combined with playfulness, a strong sense of the surreal and a willingness to delve into the bleakest of places, typified the life and practice of the artist who established himself with a series of “crawls”. The first of these endurance performances, in 1978, involved him crawling the length of New York’s 42nd Street on his hands and knees, wearing a cheap suit and clutching a potted plant. He conducted many more, including a 22-mile crawl along Broadway, which he called The Great White Way, while dressed as Superman with a skateboard strapped to his back. He told us he preferred to launch these crawls unannounced, quietly drawing attention to the brutal quality of these streets, and the people who lived closest to them, in a city that invites the viewer (and inhabitants) to only “look up”. The streets in question were selected to illustrate the massive wealth inequalities present along their length – Broadway, for example, runs through the popular theatre district but ends in the Bronx, where his mother then lived.

-Photo-Andy-Stagg-1-6.jpg)

William Pope.L. Chickens storm the Capitol in the film Small Cup, 2008. Video with colour and sound, 12:52 min. Photo: Andy Stagg.

Collaborating closely with the team at South London Gallery, Pope.L revisited old works and created some new ones, responding to the split site, the shipwreck/installation in the more classical gallery space, the rest inserted into rooms in the converted Victorian Fire Station across the road. He liked this arrangement, telling Gervais Marsh in an interview published in the Financial Times this month: “Divided space suggests growth and rupture, not always beneficial, not always obvious, but rife with possibilities.” Wholeness, he declared, “is a fiction”.

The wisdom behind such gnomic pronouncements was earned by a life spent all too aware of fragility and inequality. His father left early in his life and his mother struggled with drug addiction. As a result, he spent part of his childhood living with his grandmother. According to an obituary in the Guardian, when he was 11, his grandmother introduced him to a portrait painter, for whom she worked as a cleaner, and he encouraged Pope.L to draw. He gained a place at the prestigious Pratt Institute, but he had to drop out because of a lack of funds. He later went to Montclair State College (now Montclair State University) and Rutgers, enhancing his art studies through the Whitney Museum’s Independent Study Programme. He mixed performance and acting with fine art, including photography, video and painting, ending up as a professor at the University of Chicago. As he told us at the South London Gallery, one of his fears when undertaking his early crawl performances – which were inspired by the disgorging of mentally frail people on to the streets of New York in the 1970s, emptying out the sanatoriums “for budgetary reasons” - was that he would encounter his father and brother, both of whom were homeless at that time. “I never did,” he said. “New York is huge. But you never know. New York is also very strange.”

.jpg)

Installation view, William Pope.L: Hospital, South London Gallery, 21 November 2023 – 11 February 2024. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

When Heller invited Pope.L to share his inspiration for Hospital, he said: “I wanted to initiate a conversation about care and precarity. I mean, what is the art world – as cruel as it can be - how is it in the business of care? Irony is too thin a word to describe what I’m thinking. But I do think that care is very important. A number of people in my family were nurses, and … the practice of those kinds of folks in places like hospitals, I grew up seeing that. As a child, I didn’t really understand it. I just thought: ‘You’re taking advantage of my mother.’ But as you get older, you have to start paying attention to the functioning of your body, not just as a kind of machine or system. But … there’s a growing intimacy with your body, if you allow it: not being able to control your breath, your balance, your bowels, what you can eat. All those things force you to be in closer relationship to your 24-hour day, and in relationship to other people. And I have people in my life now who spend more time in hospitals. And the smell of the hospitals, and the lighting, and the way gravity works in a hospital. All these people on their backs all the time. You don’t know when you go to a hospital that you’re going to leave it. Even if you’re young. Especially now there are people who need treatment but can’t go to hospitals because they might get an infection. It’s really kind of interesting, the ecology of hospitals.”

Red plastic 'butcher’s shop' strips, installation view, William Pope.L: Hospital, South London Gallery, 21 November 2023 – 11 February 2024. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

Recalling those comments as I re-enter the main gallery in January, to stare at the toppled white towers, they become especially haunting. Did Pope.L know he was ill when he created this show? He had certainly been spending time in hospitals – and looking at his comments now, it seems it was not simply as a visitor: he told the FT that hospitals for him were a place of dislocation – “not just a physical dislocation but a spiritual dislocation”. And this sense of a system on the point of collapse is vivid as you stare at the looming and teetering, pointlessly perilous and disconnected toilets, some stuffed with newspaper, piles of which lie around the structure, their contents obscured by many layers of white paint and dust.

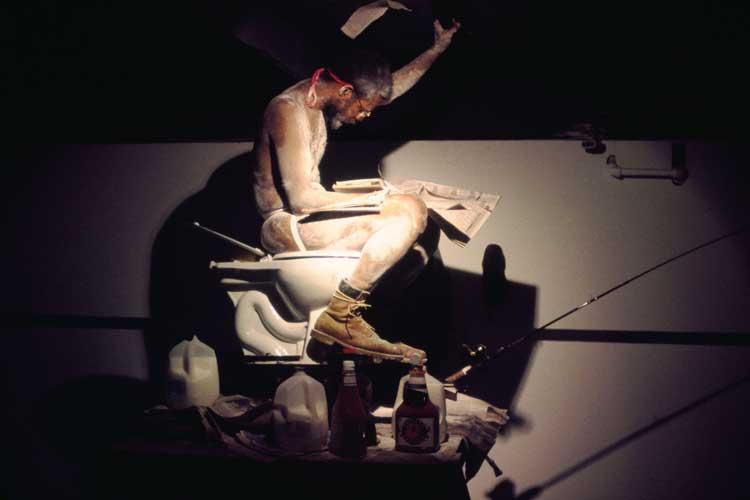

William Pope.L. The 2000 version of The Tower Eating the Wall Street Journal. MoMA, New York.

In the 2000 version of this work, titled Eating the Wall Street Journal (now owned by MoMA New York), the tower was a kind of crow’s nest, with the artist perched on a toilet at its apex, where he was eating the Wall Street Journal dipped in milk and ketchup, while lowering sections of the paper to visitors, on fishing rods. He told us he was parodying the newspaper’s claim that merely buying a copy would make you richer – in which case, surely ingesting it would be even more enriching.

For the South London Gallery version, he told us: “Initially, the idea was to have performers crawling up from one tower to the next, doing these acts, eating newspapers, drinking milk. Then I decided it would be interesting to have the towers drive the interaction. And that’s what we’re getting here. But initially during the Tower version, I coated myself in flour. You always want a little bit of whiteness around.”

A disconcerting soundtrack accompanies the work. He said that when the piece was being assembled, they were recording the noises of its construction, which were then digitised and stretched out. The sound he was going for was one of sifting. There is also a creaking sound, because the structure initially had a ship-like shape, “so I was thinking creaking ships”.

-(2000-23).jpg)

Installation view, William Pope.L: Hospital, South London Gallery, 21 November 2023 – 11 February 2024. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

One of his key drivers with this show was to inspire engagement. And the works in the main gallery provoke in the viewer a need to come up close, investigate, stand back, view the work from a different angle. Bottles, some almost empty, of liquid whose lurid colours evoke cheap liquor or sterilising fluids, are lined up on shelves around the perimeter, their contents dribbling into saucers with a steady plip. Stains that bear no relationship to the positioning of the bottles also dribble along the shelves and down the walls. There are bowls of dust that we are invited to sprinkle on to the towers. This impetus to encourage exploration is also experienced in the curation at the Fire Station, where one room features a series of small drawings placed flat against a shiny aluminium wall, the room left entirely dark so you have to grab a flashlight (offered at the door) or use light from your phone to find the work – the shiny wall becoming as much a part of the experience as the drawings.

.jpg)

Space Between the Letters Drawings, 2013. Installation view, William Pope.L: Hospital, South London Gallery, 21 November 2023 – 11 February 2024. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

No wonder he has called them Space Between the Letters Drawings (2013). Showing in the room beside them is Small Cup (2008), a film that is equal parts comically absurd and politically bleak. It shows a group of hens and goats, apparently storming a building that resembles the Capitol in Washington, pecking at and strutting around among the seeds with which it has been covered. The camera pans back at intervals to reveal the empty textile mill that provides the bleak, wintry, post-industrial setting for this vignette; the grinding soundtrack reminds us of the work and employment once offered there.

Marigolds scattered across the Fire Station entrance. Installation view, William Pope.L: Hospital, South London Gallery, 21 November 2023 – 11 February 2024. Photo: Andy Stagg.

There are marigolds strewn around the Fire Station, refreshed on a weekly basis, with petals scattered across the floor, on trajectories dictated by visitors’ feet. When asked why interaction was desirable, Pope.L said: “I think some artists might disagree, because, you know, you want to seem important. But getting people … to want to come and look at your stuff and discourse with it, I mean, in many cases they are more interesting than what you make. But who wants to admit that? So, there should be a porosity to the work when you’re building it, envisioning it. I guess it’s my theatre and performance background, but I feel that’s inescapable, so why not just lean into it. Even if you’re doing something very object based. I mean, that’s why I like to use organic things – like onions, or flowers - that change over time.”

Was it the art world’s place to be questioning our sense of who and what should be cared for, and how that should happen? “When you turn it into art, it becomes a commodity,” he said. “Some of these things are so layered with their opposite. I’m always interested when artists talk about empowering others, but they’re in this machine of art, where a lot of that machine is about not doing that at all. If you’re going to do it for real, maybe you shouldn’t be doing it in art. Or maybe we should be talking about the problematics of that more than we do. People will talk about care and precarity, but they won’t talk about how it’s sewn into a system where that is not important.

“You want your agency to be clear – as if agency is ever clear. That’s why if I do certain things and I want to do it to be helpful, I don’t tell anyone. That’s why a lot of the time when I did crawls, I didn’t tell anyone. And it took a long time for people to accept that they could be considered a part of the discussion or conversation. And there were black people who told me: ‘You shouldn’t do that because it makes you look bad.’ There’s a lot of layers to these things. Often when you seem to be super positive, people don’t get it. But I don’t want to be positive about it. I’m not.”

Installation view, William Pope.L: Hospital, South London Gallery, 21 November 2023 – 11 February 2024. Photo: Andy Stagg.

That pessimistic remark packs a particular punch on my January visit, standing in one of the upstairs rooms in the Fire Station, looking at a shelf, covered in a sticky reddish-black residue (is it wine, is it blood?), punctured by upturned green bottles, below which is a row of empty, plastic hospital carafes. And below that, a line of white saucers, empty but upturned, waiting to receive. The longer you stare at it, the more the dots connect: a system is here, but it has been stripped of its meaning, as well as its purpose.

The scent of marigolds is also overpowering on this visit, carrying a fresh, floral fragrance but also a strong note of decay. The symbolism of marigolds includes that of purity, auspiciousness, a belief that they ward off negativity and evil spirits. But Victorians also loved to use them at funerals, for remembrance, to pay tribute to the deceased. Their presence seems all the more poignant. I think Pope.L would have approved, given this tragic and unexpected development.

There is widespread mourning at the early passing of an artist who had so much more to contribute, especially to the dialogue around race and equity, and given the expectation that this UK show at a highly regarded gallery would spark renewed interest in his work in Europe and beyond. In the US, his legacy is more assured, with major retrospectives having been held in 2019 across the Whitney and MoMA New York. Either way, as Heller says: “His death marks the loss of a hugely significant artist.”

•Pope L: Hospital is at South London Gallery, London, until 11 February 2024. William Pope.L, born in 1955, died on 23 December 2023.