The Saatchi Gallery, London.

January - December 2005.

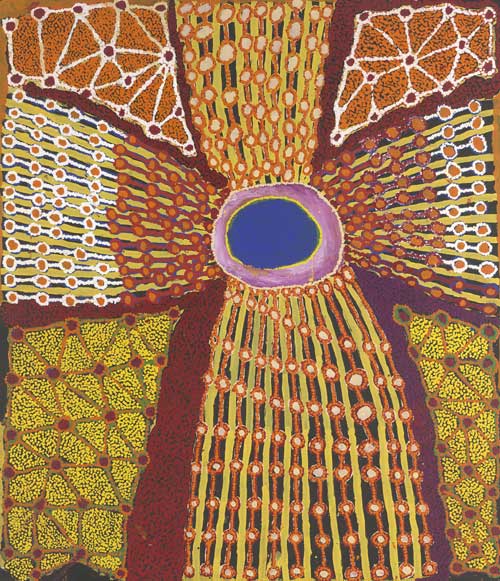

Colour Power: Aboriginal art post 1984

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

27 November 2004 - 14 March 2005.

Martin KIPPENBERGER, 'Self Portrait', 1988. Oil on canvas, 200 x 240 cm. Copyright Saatchi Gallery

This is not in any way a definitive survey, or indeed the best available, but it is nevertheless an important exhibition and one that shows Saatchi's remarkable conviction and confidence. Numerous important painters are conspicuous by their absence and many young artists are elevated to new heights. It is a curious coincidence that another unique exhibition which celebrates painting per se is taking place 12,000 miles away at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) in Melbourne, Australia. For those who feel passionately about pigment and the power of the painted image, 'Colour Power, Aboriginal art post 1984', is simply the most wonderful experience. As Gerard Vaughan, Director of the NGV, states in his foreword, 'The visual art of indigenous Australia has a stronger presence, diversity and dynamism than ever before in its history. Many Australians have been looking at, thinking about, and - consciously or unconsciously - absorbing this new art for at least 20 years. It is impossible to deny that Aboriginal artists have transformed the way we see our land and the history of Australian art. In fact, Aboriginal art, in all its diverse forms, has become the mainstream of contemporary art practice.'1

Perhaps in Britain, mid-winter, one is bound to feel homesick for the sunshine and candour of Australia, but the contrast between the two exhibitions, which celebrate painting itself, could not be more marked. Perhaps this is what Brian Robertson and Sir Kenneth Clark experienced in the early 1960s, when they saw in the work of Australian artists Sidney Nolan and Arthur Boyd a raw, passionate response to landscape and life that could only exist in a new country. A number of the most exciting and beautiful works in the Melbourne exhibition are painted by various artists; they are collaborative paintings, exuding all manner of detail, with thrilling colours that make references to places and to the cycles of life. There is an energy in these works that celebrate life, while at the same time acknowledging every bit of struggle - individual and collective. As images of abstract balance and skill, they are unsurpassed. There are also examples of sculpture, photography, body painting, rock art and bark paintings as well as paintings on canvas. The combination of traditional and indigenous forms of representation is, of course, not unique to Australian cultural issues; in fact what seems so relevant to the world at large is the successful nature of cultural bricolage:

Desert Aboriginal ground, body, implement or rock art employ earth pigments, animal products, plants, and feathers. Each material, in a manner Levi-Strauss associates with 'bricolage', retains its association with its source, origin and locale and brings these into the work as elements of its own meaning ... Thus colour is only one basis for identifying, choosing, and then 'reading' a medium. But with acrylics, colour is the only basis for differentiation. This radical difference in the semiology of materials can take some getting used to, but in the end may free the artists in another sense, presenting new choices unavailable to the bricoleur.2

As Judith Ryan observes in her excellent catalogue essays, the work on show at the NGV is driven by deep political and cultural necessity. Cultural pride on the part of Aborigines against the appalling treatment of Aboriginal culture by white settlers from 1788 onwards has resulted in a diverse art with rare and powerful qualities. The dialogue that accompanies this cultural phenomenon is of the highest standard, with heartfelt observations. The catalogue to accompany the present exhibition is the sixth major catalogue to be published on different aspects of the gallery's indigenous collection. It is illustrated in full colour, with scholarly essays documenting different aspects of the complex issues surrounding Aboriginal art. As Marcia Langton notes, 'It is not coincidental that the centres of the most highly prized genres of Aboriginal art purported to be 'traditional' are former missions or settlements - the sites of contrast between two religious or cosmological systems.'3 Judith Ryan explains:

Like any other form of contemporary art, Aboriginal art participates in a global art market and is subject to the same arbitrary market forces and the greed principle. Yet as much more becomes known about individual artists and particular cultural traditions, it becomes increasingly difficult to talk about Aboriginal art in the abstract, as if it were something generic. The use of other general categories creates tensions and contradictions that fail to acknowledge where individual artists fit or how they position themselves. If artists signal their work as Indigenous, they are potentially 'ghettoised'; but if Indigenous art is absorbed within broader categories of Australian art or contemporary art, it is in danger of being homogenised or stripped of complexity and specific context.4

Ethical and cultural issues create a sense of urgency and provide a raison d'être for the Aboriginal exhibition in Melbourne and also for the high level of cultural debate. Individual artists from as many as 17 separate communities throughout Australia are represented in the NGV exhibition; the work of 109 artists is included in total. With their feet firmly on the ground in more than one sense, these individuals infuse a sense of need and importance to contemporary art practice. This clearly does not exist in any shared cultural form in the Saatchi Gallery exhibition. For while the large and finely illustrated catalogue, 'The Triumph of Painting', is a credit to Saatchi's enterprise, the publisher's claim that it is the first publication to make coherent the vital currents of painting as 'the fundamental root of artistic expression'5 is an exaggeration. The two essays, in fact, only comprise four of the 367 pages, and while valid in their observations, they are inevitably limited in scope.6

Tjuruparu WATSON, Ngaatjatjarra born c. 1935. 'Natjula' 2003. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas 156.0 x 148.0 cm. Purchased, 2003 © Tjuruparu Watson, courtesy of Irrunytju Community Inc.

Part 1 of 'The Triumph of Painting' includes work by Martin Kippenberger, Peter Doig, Marlene Dumas, Luc Tuymans, Jörg Immendorf and Hermann Nitsch. The work of Immendorf in this context is perhaps the most impressive and significant. Commentators have enjoyed the opportunity to herald the rebirth of painting, as pronounced by the giant of contemporary art patronage. Saatchi himself is more qualified when he describes the significance of painting in the past 20 years as inevitably informed by media, conceptual art and photography:

Contemporary painting responds to the work of video makers and photographers. But it is also true that contemporary painting is influenced by music, writing, MTV, Picasso, Hollywood, newspapers, Old Masters ... I don't have a particularly lofty agenda with 'The Triumph of Painting'. People need to see some of the remarkable painting produced, and overlooked, in an age dominated by the attention given to video, installation and photographic art.7

Critics of Charles Saatchi have enjoyed making the assumption that a man who has made his exceptional wealth in the field of advertising must have had his aesthetic judgement formed by television advertising, and that this judgement must be flawed. Ironically for these critics, Sydney artist Ken Done (also shunned by the Australian art world for being a former adman and too successful in financial terms as an artist), was recently interviewed by BBC Radio Four in London. He was asked whether Damien Hirst's shark in formaldehyde - 'The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living' (1991), Saatchi's most famous work until it was sold to an American museum for £7million - was good art and whether or not it scared him. Done, who rejects conceptual art and is passionate about the painted image (which is more relevant, he believes, in a world dominated by media and photography), replied that as an Australian, he is only scared of live sharks. Issues of integrity as opposed to commercial forces, cultural identity and conflict, the new world and ancient cultures, decadent society and individual commitment all play a part in the assessment of the validity of Saatchi's exhibition. In fact, a pluralist culture relegates such pursuits as largely untenable. Besides the obvious differences, the key issue that separates the two exhibitions is the quality of the dialogue.

Charles Saatchi has been collecting art for over 30 years and showing it for the last 20 years in his own gallery in London. His early exhibitions reveal a wide range of interests in the visual arts: Donald Judd, Brice Marden, Cy Twombly, Andy Warhol, Carl André, Sol LeWitt, Frank Stella, Dan Flavin, Anselm Kiefer, Richard Serra, Philip Guston and Sigmar Polke. The impressive list continues, making Saatchi not only a discerning collector but an individual responsible for elevating the profile of contemporary art and encouraging other collectors to choose 'contemporary art rather than racehorses, vintage cars, jewellery or yachts.'8

If we believe that Charles Saatchi is announcing that painting is alive after a critical hiatus, we might be irritated by the apparently dominant role of money over integrity. But Saatchi is not making such a claim. In fact, he is critical of curators and commentators in the art world in determining trends in art. In a recent interview he stated:

The familiar grind of seventies conceptualist retreads, the dry as dust photo and text panels, the production line of banal and impenetrable installations, the hushed and darkened rooms with their interchangeable flickering videos are the hallmarks of a decade of numbing right-on curatordom. The fact that in the last ten years only five of the 40 Turner Prize nominees have been painters tells you more about the state of painting today.9

In her essay 'Moorditj Marbarn (Strong Magic)', Aboriginal artist Julie Dowling quotes Jean-Paul Sartre, who believed that 'the painter paints the world only so that free men may feel their freedom as they face it'.10 Dowling's belief that painting is her means of cultural and personal survival provides an important perspective to the notion that painting is alive in the broadest sense:

[O]n a metaphysical level, the use of pigments and materials such as ochres is a sacred act coming from sacred lands. Such pigments have power because they project these same values, while we translate the many layers of meaning we possess in our minds and hearts as Indigenous peoples. Such colours create relationships between people and the land by travelling great distances throughout the world on bark boards, carved objects and on canvas.11

These ideals are a far cry from the iconoclastic and, at times, pornographic images by Kippenberger, the artist singled out in the first of the catalogue essays. Gingeras observes, 'The recent emergence of Kippenbergiana in the work of many younger artists would suggest that his formal legacy has recently been codified into some sort of avant-garde sign value - where the look of awkwardness, unfinished - finish, and stylistic irregularity are understood as markers of an antagonistic position and of politico-aesthetic gravitas.'12

The Leonardo scholar, Martin Kemp, describes the very stuff of painting in relation to the work of Arthur Boyd:

Its extraordinary material properties, thin and thick, translucent and opaque, the ravishing intensity of saturated pigments, and its paradoxical ability to insinuate the painter's impulses into the spectator's imagination ... painting can conjure up a world of living beings, and tell moving stories, without literal imitation of what things look like.13

'The Triumph of Painting' falls short in making connections and in pursuing the significance of the wide range of work presented. It is to be hoped that over the course of this year, as the three parts of 'The Triumph of Painting' are unveiled, commentators can give a meaningful appraisal of the cultural significance of the work of the diverse number of artists currently involved in the field of painting. Perhaps as spring turns to summer, the immediate impression of a culturally sardonic mood will lift.

Dr Janet McKenzie

References

1. Vaughan, G. Director's foreword. In: Ryan J (ed). Colour Power: Aboriginal Art post 1984 in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2004: 7.

2. Michaels E. Bad Aboriginal art: Tradition, Media and Technological Horizons. Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1994. In: Watson C. Whole lot, Now: Colour dynamics in Balgo Art. Ibid: 119.

3. Ryan J. From Reckitts Blue to Neon: The Colour and Power of Aboriginal Art. In: ibid: 99.

4. Ibid: 99.

5. The Saatchi Gallery. The Triumph of Painting. London: Jonathan Cape, 2005.

6. Gingeras AM. Kippenbergiana: Avant-Garde Sign Value in Contemporary Painting/ Schwabsky B. An art that eats its own head: Painting in the Age of the Image. In: ibid.

7. Charles Saatchi interviewed by The Art Newspaper. London: Umberto Allemandi & Co., 2004: 30.

8. Ibid: 31.

9. Ibid: 31.

10. Dowling J. Moorditj Marbarn (Strong Magic). In: op. cit: 136.

11. Ibid: 138.

12. Gingeras AM. Op cit: 7.

13. Kemp M. Foreword. In: McKenzie J. Arthur Boyd: Art and Life. London: Thames and Hudson, 2000: 13.