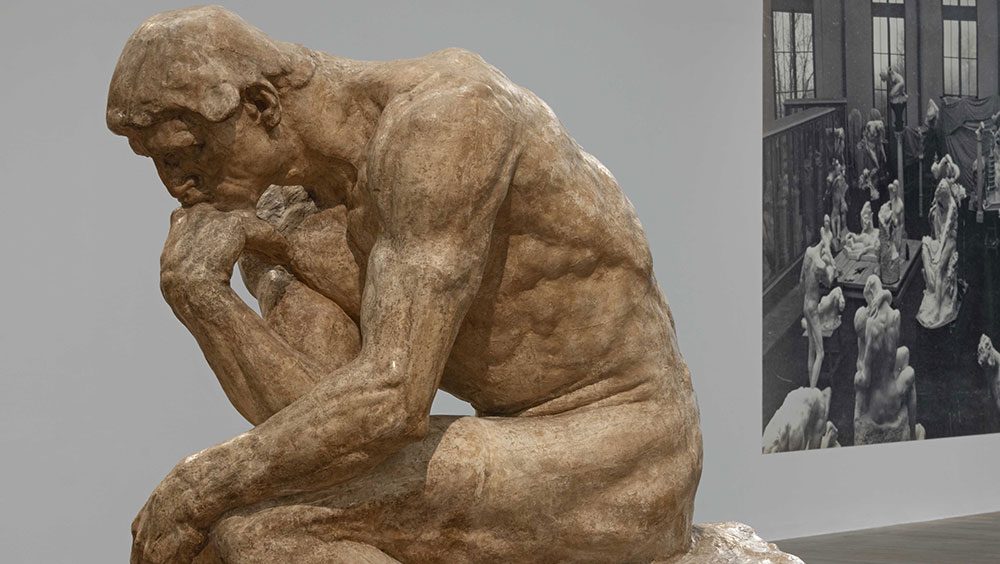

Auguste Rodin. The Thinker. Installation view, The Making of Rodin, Tate Modern, London 2021. Photo: Juliet Rix.

Tate Modern, London

18 May – 21 November 2021

by JULIET RIX

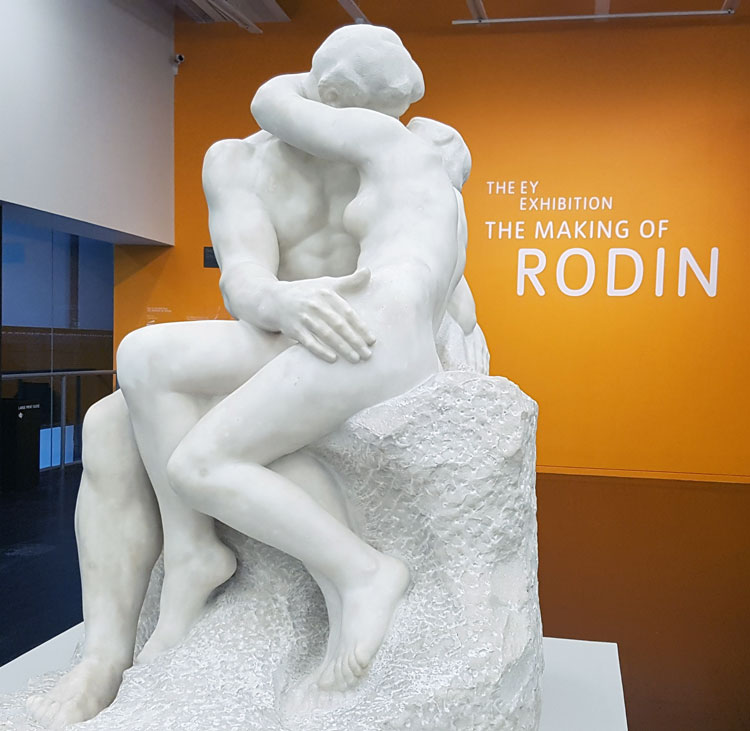

Less about what made Rodin, more about what – and how – he made, this exhibition is inspired in part by the artist’s own presentation of his plasters at the Pavillon de l’Alma in 1900 and includes copious loans from the Musée Rodin in Paris. It starts with a kiss – the Tate’s own The Kiss (1901-4), one of the three full-size versions of this famous sculpture made in the artist’s lifetime. Standing at the entrance to the show, this larger-than-lifesize marble instantly reminds us of Auguste Rodin’s extraordinary ability to express human emotion physically and fluidly, even in the hardest of materials.

Auguste Rodin. The Kiss, 1901-4. Installation view, The Making of Rodin, Tate Modern, London 2021. Photo: Juliet Rix.

Rodin (1840-1917) himself later saw The Kiss as too traditional, calling it, “a large sculpted knick-knack”. I can’t agree, but the comment does offer a window into his attitude to the development of his art, and his conscious movement away from classical and 19th-century sculptural norms.

This show takes us on that journey, largely in plaster. Not normally the material of the finished product, it was nonetheless in plaster that Rodin presented his own work at his “museum” at the Pavillon de l’Alma in Paris and then at his studio in Meudon, on the outskirts of the city.

The first room, however, is an exception. It contains The Age of Bronze (c1877), a single bronze male nude, a piece clearly influenced by a trip that Rodin had recently made to Florence, and the work of Donatello and Michelangelo he had seen there. Rodin’s figure has the same intensity as their Florentine Davids, and his choice of a raised-elbow pose echoes that of Michelangelo’s Dying Slave in the Louvre.

.jpg)

Auguste Rodin. The Age of Bronze, c1877. Installation view, The Making of Rodin, Tate Modern, London 2021. Photo: Juliet Rix.

One of the joys of this exhibition is that you can get very close to much of the work, and often circle it for the full 360-degree experience. It makes for an intimate relationship between viewer and sculpture and allows proper examination of individual elements and surfaces.

When it was first exhibited in Paris, The Age of Bronze was considered so life-like that Rodin was accused of cheating and casting directly from the body of his model, a young Belgian soldier. Rodin had, in fact, modelled the work by hand in clay, and was so offended by the accusations that he commissioned photographs of the soldier’s anatomy to show how the sculpture differed. From then on, he tended to work in greater than or less than life-size, and the attacks may have accelerated his move away from the perfected realism of the classical ideal and towards more textured surfaces, and work focused on ideas and the interior life.

-Rodin-JR.jpg)

Auguste Rodin. Balzac (large and small). Installation view, The Making of Rodin, Tate Modern, London 2021. Photo: Juliet Rix.

This shift is immediately apparent in the next room, where the viewer is confronted with both The Thinker and Rodin’s oversized statue of Balzac – along with a variety of three-dimensional studies for, and variations on, both works. On the wall is a telling quote: “What makes my thinker think is that he thinks not only with his brain, with his knitted brow, his distended nostrils and compressed lips, but with every muscle of his arms, back and legs, with his clenched fist, and gripping toes.”

The Balzac, too, Rodin stated, was more about the writer’s character than his appearance. Having been commissioned to produce a commemorative statue of the French man of letters, Rodin spent seven years experimenting with how to present him. Here we see many bits of Balzac-in-the-making – belly, head, naked body, empty dressing gown – as well as versions of the whole, both vast and small.

The rotund, cave-eyed, wild-haired figure, completed in 1898, was not to the liking of the commissioners, so Rodin installed it in his own home studio. It was not until 1939, 22 years after the artist’s death, that the piece was finally cast in bronze and installed on the Boulevard du Montparnasse, adding to Rodin’s considerable contribution to the modernisation of public memorial sculpture.

.jpg)

Auguste Rodin. The Thinker. Installation view, The Making of Rodin, Tate Modern, London 2021. Photo: Juliet Rix.

The Thinker was originally intended as a key figure (among 180) on the Gates of Hell, a planned set of monumental bronze doors based on Dante’s Inferno for a fine arts museum in Paris. The museum never happened, but the commission resulted in several figures that broke out of the composition to take on a life of their own (The Kiss was another), reappearing repeatedly in Rodin’s work in a range of sizes and contexts. In one of the more extreme re-settings, The Thinker’s foot became a pre-surrealism surreal artwork in its own right – Left Foot of the Thinker on a Fluted Pedestal with Foliage (after 1903) – also on show here.

Auguste Rodin. Assemblage of Reduced Heads of Jean d’Aire and Jean de Fiennes and Hands, topped by a Winged Figure, after 1899. Installation view, The Making of Rodin, Tate Modern, London 2021. Photo: Juliet Rix.

Rodin increasingly fragmented, repeated and assembled elements of previous works to create something new. Highlighted throughout the show, this tendency perhaps culminates in the surreal assemblage of the heads of the Burghers of Calais embraced by an angel-like figure (Assemblage of Reduced Heads of Jean d’Aire and Jean de Fiennes and Hands, topped by a Winged Figure, after 1899).

While working on the Gates of Hell, Rodin developed a catalogue of body parts, what he called his abattis (giblets). These 3D sketches in plaster and terracotta served a similar purpose to the collections of parts and poses used by Renaissance artists. A vitrine here displays, like a morbid Victorian museum case, a multitude of hands – clawed, clenched, pointing and open. The poet Rainer Maria Rilke, for a while Rodin’s secretary, describes miniature arms, “so full of life that they make your heart beat faster … hundreds of them there, not one like another”.

Auguste Rodin. The Hand of God, 1898. Photo: Juliet Rix.

Several assemblages speak to Rodin’s interest in hands – and the power they can represent. The Devil’s Hand (1903) and The Hand of God (1898) – which, incidentally, reuses the hand of one of the Burghers of Calais (Jacques de Wissant) – show little human figures literally caught in the grip of a higher power. Large Left Clenched Hand with Imploring Figure (c1890) finds the little human pleading before an unyielding manus.

-Rodin-JR.jpg)

Auguste Rodin. Hanoko Mask, type D, 1910-11. Installation view, The Making of Rodin, Tate Modern, London 2021. Photo: Juliet Rix.

Most of these overpowered figures appear to be female, and the show offers a nod to Rodin’s feminine muses. Hélène von Nostitz, Ohta Hisa (Hanako) and the highly accomplished artist Camille Claudel each get a full page of the accompanying booklet, but only passing reference in the exhibition itself. This feels a bit apologetic; better, perhaps, to accept that this show is Rodin’s or do the job properly. The works are entirely legitimate exhibits, of course, including a tensely emotional “mask” of Hanako’s face and an extraordinarily innocent-looking bust of Claudel, delicate fingers to her mouth (Farewell, c1905), made some years after the end of their relationship.

-1905-Rodin-JR.jpg)

Auguste Rodin. Farewell (L'Adieu) 1905 (Camille Claudel). Photo: Juliet Rix.

A second head of Claudel is assembled in a slightly disturbing combination with the oversized hand of Pierre de Wissant (Mask of Camille Claudel and Left Head of Pierre de Wissant, after 1900). Wissant, with his brother Jacques, was also one of the six Burghers of Calais who offered to sacrifice themselves to save the city when England’s Edward III laid siege in 1346-7.

The six burghers were ultimately spared, but Rodin, commissioned to produce a monument for Calais in 1884, depicts them as they walk to expected execution. As you might expect, he shows them not as heroic archetypes, but as individuals, each suffering his own internal emotions, in this theatrical in-the-round sculpture.

The original intention was to place the sculpture on a high plinth but, in the end, Rodin decided it should stand on the ground, and so it does in this exhibition. It places us among the men – the disconsolate, the disbelieving, the desperate – close enough to easily see the vulnerability of the oversized bare feet and expressive hands.

If you want to see a finished bronze cast of the Burghers – on a lowish plinth – it is a pleasant walk along the Thames from Tate Modern to the Houses of Parliament and neighbouring Victoria Tower Gardens. Here, with Rodin’s own involvement in positioning it, the sculpture has stood since 1914.