Archie Brennan, Chain, 1979 (detail). © The Estate of Archie Brennan. Photo: Michael Wolchover.

City Art Centre, Edinburgh

13 November 2021 – 13 March 2022

by BETH WILLIAMSON

It is 10 years since the City Art Centre in Edinburgh hosted a tapestry exhibition. In this current group exhibition, it is not always straightforward to recognise the work as tapestry, but that is partly the point. The 19 artists included are all associated with the former tapestry department at Edinburgh College of Art. The department may no longer exist, but from the 1960s to the 2000s it was a hub of creative innovation where tapestry was taught on an equal footing with other fine art disciplines. Teaching and learning favoured pedagogical strategies that facilitated an open approach with a broad understanding of what tapestry could be. While students did learn to weave, they were also encouraged to explore their ideas through a wide range of different media. Warp and weft may have been the basis of their training, but many students, and staff, went on to develop their practice far beyond this. Rather than looking solely to the traditions of tapestry, many practitioners also embraced new subjects and techniques. Drawing, installation and sculpture all took their place within the overarching practices of the tapestry department and they now take their place within this exhibition. As the curator Maeve Toal writes of the works in this exhibition: “Where it was once seen as a craft, it is now considered an artform in its own right, underpinned by ideas as much as technique. These works break with convention, looking to the future rather than the past.”

The artists included in the exhibition work in diverse ways. That stems from their backgrounds at the college where, as the curator and academic Lesley Miller writes: “Tapestry was seen and taught as an art form with content, technique and individual voice given equal value.” This is a far cry from the large-scale tapestry wall hangings commonly seen in country houses and corporate lobbies. Instead, there is a vibrant collection of contemporary work, ranging from live collaborative performance to sculpture responding to the pandemic, and much else besides. All these artists use what has been termed as “tapestry thinking”, meaning a concern with ideas expressed through tapestry in its widest sense.

Archie Brennan, Chain, 1979. © The Estate of Archie Brennan. Photo: Michael Wolchover.

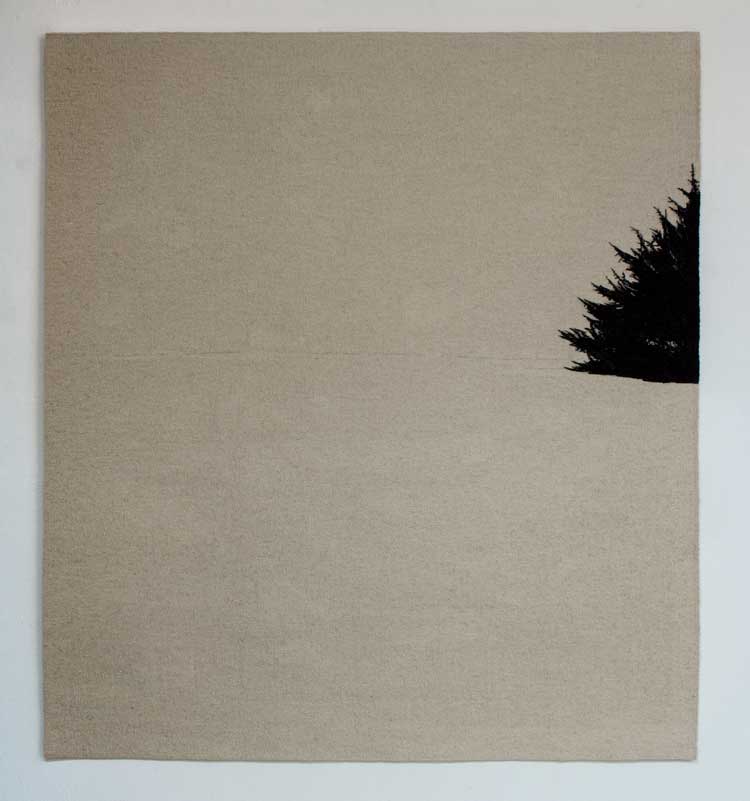

What first struck me in this exhibition, apart from the tapestry department that spawned it, was the network of generational and material connections. Archie Brennan (1931-2019) was a founder member of the department and, also had a long and successful career at Dovecot Studios, from apprentice to artistic director. Essentially a pop artist, his tapestry Chain (1979) may use conventional methods and materials, but the subject, an image of an oversized linked metal chain, is certainly an unconventional one for tapestry. Sara Brennan inherited yarn from her father, Archie, and that yarn plays a large part in her creative response to landscape. She works from original drawings and, as she explained in 2017, her work is “a direct response to the reaction and relationship between yarns, with a disciplined and restrained approach to colour, tone and form. Choosing each yarn is as important to me and the tapestry as making the original drawing.” We can see evidence of this restrained approach to colour, tone and form in her work Tree Line I (2021).

Sara Brennan, Tree Line I, 2021. © the artist. Photo: Michael Wolchover.

Gordon Brennan, Sara’s cousin, was also an apprentice at Dovecot Studios and taught at all four Scottish art schools. His enamel on plywood works in this exhibition, such as Rest (2020), are made from discarded wood and furniture that he has reclaimed and painted entirely in enamel. Even the backs of works are painted so that, when mounted on the wall, a soft colourful glow emanates from behind.

Gordon Brennan, Rest, 2020. © the artist.

.jpg)

Henny Burnett, 365 Days of Plastic (detail), 2020/2021. © the artist. Photo: Martin Urmson.

Henny Burnett’s 365 Days of Plastic (2020-21) is a fascinating work made in response to lockdown. Every plastic food container she used during this time was cast in dental plaster and became part of the work. The use of dental plaster referred to the mouth and the act of eating food.

Fiona Mathison, My Lockdown Lover, 2021. © the artist. Photo: BJ Stewart.

One of Fiona Mathison’s works – My Lockdown Lover (2021) – also came out of lockdown and is accompanied by the exquisite Hold on Tight (2017-18). My Lockdown Lover is a woven hot-water bottle and Hold on Tight is made from a number of tiny woven hands assembled into a tight ball.

,-2021.jpg)

Jo McDonald, Networking (detail), 2021. © the artist.

I was particularly struck by the work of artist Jo McDonald in this exhibition, especially her piece Networking (2021). I was fortunate to be able to speak to the artist about her practice using secondhand books as a key material. McDonald collects old books and sorts them according to the tone of the page colour, ranging from light cream, through beige, to darker almost brown colours. Once sorted, each page is cut into tiny squares that are painstakingly threaded on to long strands of monofilament. These strands of handmade material are then used in different ways. In the case of Networking, they are individually attached to old wooden bobbins and tumble to the floor, giving a sense of both the history and the future of tapestry and textiles work. Here, McDonald’s focus is on the colour and materiality of the books used as the basis of her work. In other cases, the content of the books themselves, the stories within, are important, too, as in the poignant case of a work she made from her father’s books.

Joanne Soroka, Migration, 2017. © the artist. Photo: Michael Wolchover.

There is so much to see and think about in this exhibition. Joanne Soroka’s works, such as Migration (2017), look like maps and deal with the sorts of political and humanitarian questions we perhaps do not expect tapestry to grapple with. Lesley Stothers’ Composing a Life (2013) pushes the boundaries of tapestry, too. A multimedia paper book structure, it is pierced and woven with needles, thread and cord. The book structure suggests a narrative, and the life stories we all have, while the piercing needles disrupt that narrative. Perhaps that is what this exhibition does. On the one hand, it disrupts traditional narratives of tapestry. On the other hand, it creates a new more open narrative, one that will, hopefully, continue to expand and develop ad infinitum.

Lesley Stothers, Composing A Life, 2013. © the artist. Photo: Roland Paschhoff.