Simone Leigh, Cupboard, 2022. Bronze and gold, 88 1/2 × 85 × 45 in (225 × 216 × 114.3 cm). Right: Sentinel IV, 2020. Bronze, 128 × 25 × 15 in (325 × 64 × 38 cm). Installation view, Simone Leigh, the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2023. Photo by Timothy Schenck.

Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston

6 April – 4 September 2023

by LILLY WEI

Framed by the entrance to the exhibition is a gilded bronze figure of a Black woman, larger than life but only slightly so, scale a significant motif throughout this venture. She is naked to the waist, clad in a wide, tiered skirt, the pleating suggesting bundled raffia stretched over a European-style hoop, the lighting boosting her radiance to goddess wattage. She looks impassively outward over our heads, the aloofness not only attributable to her hieratic pose but also to her sightlessness, lacking eyes – as well as ears, arms and hands, and her legs invisible beneath her clothing – but emphatically not lacking regality, dignity and authority. Titled Cupboard (2022), that humble object is now invested with new significance, new value, its associations improbably glamourised. Also in the first gallery is its complement, Sentinel IV (2020), a giant beanstalk of a figure in black bronze that stretches towards the ceiling, its breasts and buttocks barely noticeable bumps, a disproportionately large semi-ovoid head its most pronounced feature. Both sculptures, their body stereotypes toyed with, adapted, are firmly planted on the ground, suggesting gatekeepers, guardian figures. Over the doorway is the name of the artist writ large in straightforward but elegant lettering: Simone Leigh.

Installation view, Simone Leigh: Sovereignty, US Pavilion, 59th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia, 2022.

Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo: Timothy Schenck. © Simone Leigh.

Leigh, whose career has skyrocketed in the past few years, was widely acclaimed for Brick House, a soaring dome-shaped bronze torso of a young Black woman that was the inaugural commission for New York’s High Line plinth in 2019, dramatically positioned on the spur that straddles 10th Avenue, her breakthrough work. Borrowing the title from the Commodores’ 1997 hit song, she also “shakes” things “down”, slyly turning an objectifying – and objectionable –anatomical descriptive for women, the scatological term between brick and house left out, into a signifier of Black beauty, and of shelter, sanctuary and empowerment, the idea of house and home a recurrent, proprietary theme in Leigh’s work. She represented the US in Venice in 2022, the project sponsored by Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) and overseen by its chief curator and deputy director of curatorial affairs, Eva Respini (who is stepping down at the end of this month), who is also the curator of this survey, the artist’s first. Of the 29 works in this show spanning 20 years of her practice, nine are from Venice, including the vigilant, towering, part West African, part technologically inspired Satellite (2022), placed outside the ICA.

Simone Leigh, Satellite, 2022. Bronze, 24 × 10 × 7 ft 7 in (7.3 × 3 × 2.3 m). Installation view, Simone Leigh, the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo: Timothy Schenck. © Simone Leigh.

The works, wending their way through nine galleries plus a corridor space, are interrelated, representative of the strength, resilience, endurance and knowledge of Black women in the aggregate, and not individual likenesses. However, there is one that is a portrait, her first, a tribute to the historian Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts, and others are dedicated to pioneering Black women, such as the dancer and choreographer Katherine Dunham and the poet Gwendolyn Brooks. (It also seems that the lips and noses of some of Leigh’s otherwise featureless faces might be her own?)

Simone Leigh, Sharifa, 2022. Installation view, Simone Leigh, the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2023. Photo: Timothy Schenck.

In a critique of race and gender, she packs her work with references and inferences to African and Caribbean history, culture and politics, to ethnographical studies, colonial and postcolonial theory, and more. The materials are equally weighted, politicised, tied to the economy of those regions and systemic inequities, in particular cowrie shells and raffia (she covered the US Pavilion with the tropical fibre to transform the Monticello-like, colonialist building into thatched African housing), deployed throughout the exhibition.

Simone Leigh, Cupboard IX, 2019. Stoneware, raffia, and steel armature, 78 × 60 × 80 in (198.1 × 152.4 × 203.2 cm). Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston. © Simone Leigh.

Cupboard (2022), another version of the series, substitutes a ceramic cowrie shell for the figure’s head, placed on a domed steel hoop covered with raffia that, again, suggests a village dwelling, once again equating the female body with home conceptually and house structurally. Leigh, who only in the last few years has been working in bronze and steel – the choice and combinations of materials also political, metaphoric, from the fragile to the unbreakable – is a masterful ceramist and an ardent advocate of an ancient medium still dismissed at times by the western art world as the lesser production of marginal societies and as handicraft to be executed by women (although few non-western civilisations concur, considering it one of their highest forms of aesthetic expression – but, if so revered, are usually, inevitably credited to male artists.)

Simone Leigh, Martinique, 2022. Stoneware, 60 3/4 × 41 1/4 × 39 3/4 in (154.3 × 104.8 × 101 cm). Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo: Timothy Schenck. © Simone Leigh.

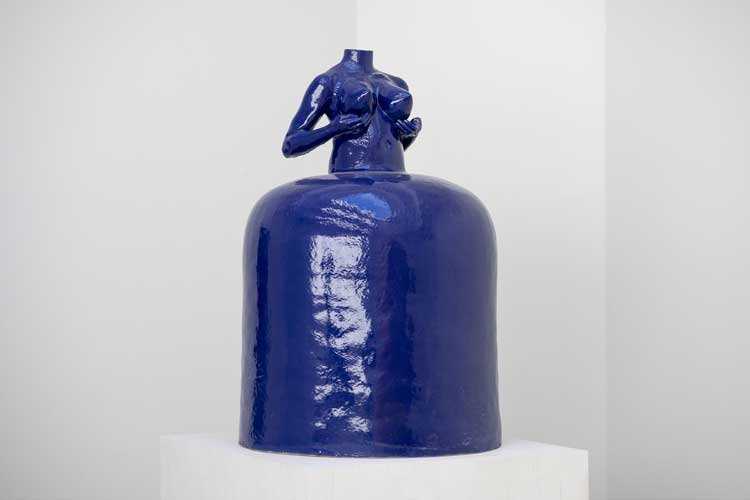

Vessels, often jugs, with female faces and bodies or incorporated into the figure to underscore female identity as a receptacle, comprise much of the exhibition. These composite images are in porcelain, stoneware, terracotta and bronze, transformed from housewares into objects of beauty and affirmation: Martinique (2022), a five-foot stoneware female figure without a head and in Leigh’s trademark domed skirt (not unlike the sheltering robes of the Madonna della Misericordia), its gorgeous cobalt-blue glaze sufficient reason for its existence. One recent head is bright yellow, its tightly curled hair a focal point, making us almost forget its absent eyes, reminding us of the enormous signification of hair in Black culture, although with differences, meaning one thing to African Americans and another to women from Africa and the Caribbean islands. (And with differences across time and space, the head having a superficial resemblance to the iconic snail-shell curls of the Buddha or the drilled coiffures adorning the marble heads of Flavian matrons).

Simone Leigh, Anonymous (detail), 2022. Stoneware, 72 1/2 × 53 1/2 × 43 1/4 in (184.2 × 135.9 × 109.9 cm). Private collection, Boston. Photo: Timothy Schenck. © Simone Leigh.

Anonymous (2022), in lustrous, co-opted white (it is always bracing to wonder what Leigh intends and does not), taken from a historic photograph, is rescued from its source as a figure of mockery and transformed into one of winsome tenderness, her head gently tilted, about to rest her face in her hands.

Girl (Chitra Ganesh and Simone Leigh), my dreams, my works, must wait till after hell..., 2011. Installation view, Simone Leigh, the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2023. Courtesy the artists and Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo: Timothy Schenck.

There are three videos on view here, all collaborations, one with the artist Chitra Ganesh from 2011, depicting a blown-up projection of a brown-skinned female closeup, only her back visible. She is very quietly breathing but otherwise, nothing much happens, her head buried under a heap of broken stones. The title is from a Brooks’ poem, My dreams, my works, must wait till after hell…, although, given the present more positive, progressive environment, we might hope that this sleeping beauty will not sleep for ever.

Simone Leigh, Last Garment, 2022. Bronze, steel, metal, filtration pump, and water, 54 × 58 × 27 in (137.2 × 147.3 × 68.6 cm) (sculpture); dimensions variable (pool). Installation view, Simone Leigh, the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo: Timothy Schenck. © Simone Leigh.

Last Garment (2022), the penultimate work in the show, is also the most realistic. A life-sized figure of a slender young Jamaican laundress bent over a rock, looking down, diligently scrubbing, is submerged to her ankles in a dark pool of water that occupies the entire gallery; she is alone, looking rather lost in its vastness. It was also based on an archival photograph and summons up a host of associations, from the namelessness of this young girl, her image taken without a second thought, to the exploitation of Black female and child labour (on which both white and Black communities depend), and of similar images of young white women who, looking into a pool such as this, most likely would be admiring their charms, as would the viewer.

Leigh offers us an intensive, entangled course in colonialist history, politics, rituals, art, forcing us to confront uncomfortable truths, as related through her memorable cadre of women to whom these stories belong and who have the most right to tell them.

• Simone Leigh will tour to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington DC, November 2023 to March 2024, and there will be a joint presentation at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and the California African American Museum (CAAM) in Los Angeles in June 2024 to January 2025.