Shahzia Sikander. Photo: Andrea Rossetti.

by ANNA McNAY

Shahzia Sikander (b1969, Lahore, Pakistan) received rigorous training in the traditional practice of miniature painting at the National College of Arts, Lahore. She came to fame in the early 90s, challenging and recontextualising the medium’s technical and aesthetic framework and pioneering an experimental approach to the genre, using techniques of serialisation, cutting and pasting, and calligraphy to deconstruct archetypal narratives around femininity, race, memory and migration.

Sikander moved to the US in 1993 to study for an MFA at the Rhode Island School of Design, and, following a residency at Artpace, Houston, in 2001, she began experimenting with video and animation. She has recently added sculpture to her mixed-media practice.

Sikander is opposed to the idea of homogenous and authentic national cultures, believing, instead, that we should understand terms such as “tradition”, “culture” and “identity” as unstable, abstract and evolving. Feminine motifs, alongside the concept of art itself, provide a counterpoint of abundance, renewal and birth to the abuses of extraction, depletion and waste, about which her works so frequently comment. Text – in particular poetry – is also an important aspect of her work, which she seeks, similarly, to make “sing”.

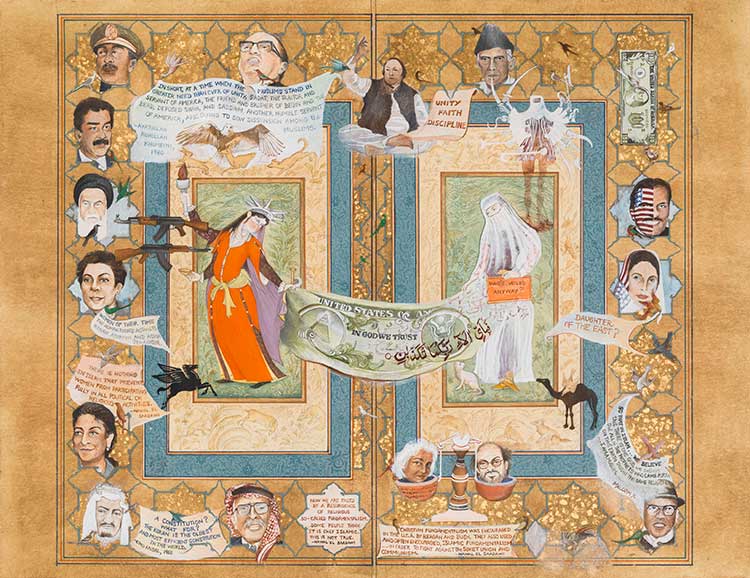

Shahzia Sikander. The Many Faces of Islam, 1999. Gouache, vegetable colour, watercolour, gold leaf, graphite and tea on wasli paper, 43.2 x 30.5 cm (17 x 12 in). Courtesy the Artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, NY, and Pilar Corrias Gallery, London.

Sikander lives and works in New York City. She had a solo exhibition, Infinite Woman, at Pilar Corrias, London, at the end of 2021; is part-way through a major touring retrospective, Extraordinary Realities, in the US; and has a further solo exhibition, Unbound, at Jesus College, University of Cambridge.

Sikander spoke to Studio International via WhatsApp about her multivalent practice.

Anna McNay: You are part-way through a major touring retrospective, Extraordinary Realities, in the US, the focus of which is on your work with manuscripts, looking back at the first 15 years of your career. What more can you tell me about this?

Shahzia Sikander: As you say, the exhibition reflects on work made more than 25 years ago, tracing the pioneering role it played in the contemporary miniature painting movement, now known as neo-miniature. It starts with works I created in Pakistan in 1987-1992 and included The Scroll (1989-1990), which became the launching marker at the National College of Arts in Lahore for reimagining the traditional genre of manuscript or miniature painting.

What is new in this survey is the focus on every work’s individual context, articulating in each case the shifting themes around art history, language, empire, diaspora, gender, sexuality and politics. The sensitive and thoughtful curation by Jan Howard allows the inherent feminist visual lexicon I was developing in that era to surface, facilitated by interactions with other artists and scholars and between various bodies of works, without an overt focus on my biography and identity, which was often commonplace in how my work was written about in the 90s artworld.

Shahzia Sikander. Unbound, 2021-2022. Jesus College, Cambridge, UK. Courtesy the Artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, NY, and Pilar Corrias Gallery, London.

Being Asian-American – or Asian-anything – in the west often means living the paradox of being invisible while standing out because it is such a broad racial category in which many different nations, ethnicities, classes, cultures, histories, communities and languages must vie to be recognised. In this in-between space, making art allows me to complicate assumptions, categories, hierarchies, centre-margin dynamics where issues of sovereignty can be loosened, conceptually emotionally and visually by using multiple languages and creating unexpected relationships. Along with the accompanying book, the exhibition expands the feminist discourse to include an international South Asian female perspective. The book, which is more academic than exhibition catalogue, is edited by Jan Howard and Sadia Abbas, an English and postcolonial professor at Rutgers University, who, like me, grew up in Pakistan and moved to the US as an adult. Other contributors are the scholars Kishwar Rizvi, Gayatri Gopinath and Faisal Devji and the artists Rick Lowe and Julie Mehretu. A conversation in the book with the curator Vasif Kortun maps the pre-9/11 artworld and overlapping diasporas. All the works in the retrospective were created in dialogue with the various communities I was part of as I moved from Lahore to Providence, to Houston to New York and the artists of my generation with whom there were overlaps, such as Mehretu, Kara Walker, Cecily Brown, Ghada Amer, Teresita Fernández, Nicola Costantino, Donna Bruton, David McGee, Barry McGee and Margaret Kilgallen. The overlapping stories are brought out in the didactics, essays, interviews and discussions.

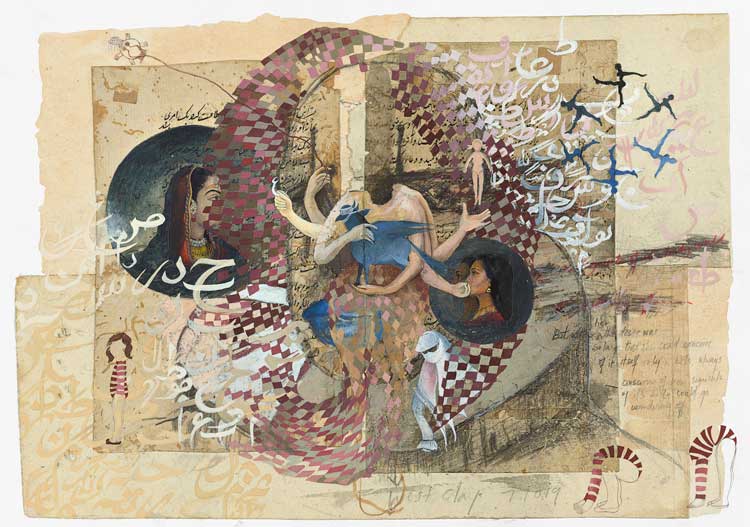

Shahzia Sikander. Segments of Desire Go Wandering Off, 1998. Collage with vegetable colour, dry pigment, watercolour, graphite, and tea on wasli paper, 24.3 x 50 cm (9 9/16 x 19 11/16 in). Courtesy the Artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, NY, and Pilar Corrias Gallery, London.

Conversations generated by the exhibit itself have been critical. Many thinkers and curators, including Fred Moten, Kelly Baum, Dipti Khera, Lisa Lowe, Jason Rosenfeld, Ayad Akhtar, Brinda Kumar, Vishakha Desai, Vijay Iyer and Du Yun, spoke about practice and collaboration in conversation with this exhibit, raising important questions around nation and diaspora, in particular about the commodification of the nation and how canons are created and who gets to be included or excluded.

The most important thing to reflect on from this travelling show is that it took me 20 years to get a solo museum exhibit in New York City, where I have been living since 1997, and not only did it sell out many times, but it proved a game-changer for the Morgan Library Museum packing in a new and diverse audience, reflecting how multilayered the diaspora audience in New York City is, including the South Asian communities, and how it cannot be boxed into one kind of template.

AMc: Language, poetry and text are important aspects of your work, and you have been inspired by several female poets and writers, including Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich and Parveen Shakir. Is that also a form of collaboration? How do you take this inspiration and incorporate it into your work?

SS: Poetry’s ability to condense and heighten an experience with words is an inspirational device. Developing a parallel process, I usually create a painting as a poem, where its formal dynamics intersect with emotional and social consciousness. My work breaches all sorts of binaries and boundaries around cultural representations and female iconographies. Early in the 90s, while imagining the interplay between multiple sides of a hyphenate reality, whether Pakistani-American, American-Pakistani, Muslim-American, American-Muslim, Asian-American, East-West, West-Islam, and so forth, I was looking into fiction and poetry to imagine and give shape to my interest in class stratifications, movement across and from one culture to another, the range of cultural differences, aspirations of immigrants, the various sites of conflict and human attention.

Whether I was reading Michele Wallace, Audre Lorde or bell hooks, or bringing them into conversation with Ismat Chughtai, Fahmida Riaz or Parveen Shakir in the early 90s, I was intuitively seeking common ground, the in-between spaces where ideas get born, performing one’s own intersectionality many moons ago. Digging into the intimacy of female experience across race and cultures was creatively similar to my digging into the historical manuscripts across central and south Asia for visual overlaps – the points of connections that may be small in scale, but could contain infinite possibilities.

Shahzia Sikander. Infinite Woman, 2021. Watercolour, ink, gouache and gold leaf on paper, 167.6 x 152.4 cm (66 x 60 in). Courtesy of the Artist and Pilar Corrias, London.

In my exhibition, Infinite Woman, at Pilar Corrias, London, I brought up Adrienne Rich through the unexpected route of Ghalib’s Urdu poetry. Rich’s translations of Ghalib and attempts to write ghazal allow me to engage with Rich by connecting translation, language and gender as equal stakeholders. When I create contemporary miniatures in which women resist simplistic categorisations, I am responding to the difficulty of finding feminist representations of brown South Asians in contemporary culture.

AMc: You were born, and studied, in Lahore, and were trained in the traditional practice of miniature painting. You came to fame in the early 90s, challenging and recontextualising this medium’s technical and aesthetic framework and pioneering an experimental approach to the genre. What made you want to study the miniature at a time when it was deeply unpopular?

SS: Our understanding of art history has long been Eurocentric and beliefs in binaries such as east-west, Islamic-western, Asian-white or oppressive-free are deeply entrenched in how we view the world. When I went to the National College of Arts in Lahore in 1987, traditional miniature painting was stigmatised as kitsch and derivative. “Miniature”, a colonial term, encompasses premodern Central and South Asian manuscript painting. There were barely any students studying it. My interest in premodern manuscripts was sparked in response to that largely dismissive attitude, as well as by a collective lack of deep cultural knowledge about the genre. Because artefacts and historical paintings from South Asia existed mostly in collections in the west or in India, my peers and I in Pakistan had few historical materials to examine. My interaction was mostly from books and exhibition catalogues printed by western institutions. I became interested in how tradition is performed, who determines art-historical hierarchies, how art history and cultural representations can remain one-sided. Notions of authenticity, nationalisms, who gets to speak about whom, cultural appropriation and gatekeeping – interest in these aspects were foundational to my interest with manuscripts.

Shahzia Sikander. Extraordinary Realities, 2021-22 (travelling exhibition). RISD Museum, Providence, RI. Courtesy the Artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, NY, and Pilar Corrias Gallery, London.

During the European colonial era in the Indian subcontinent, for example, many South Asian manuscripts were dismembered, scattered and sold for profit, stunting the canon of Central and South Asian pictorial traditions for good. The most significant manuscripts can be found in the collections of western museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the British Museum, the V&A and the Royal Library. Thousands of South Asian and Islamic art materials have ended up in the UK because of colonial histories. History itself is effectively just an account of the movement of objects and bodies. Trade, slavery, migration, colonial occupation – these are underlying currents, the root axes of modernity. How history is told, and who gets to tell it, exposes the hierarchies of power in our world.

My practice is investigative, speaking through the research and colonial archives to readdress orientalist narratives in western art history. When I cite the historical, I want the wall label to share that. Working across time and history shows up in my own work. Recently, I dug out an image from a painting I made in 2000 and made it into a sculpture in 2020.

AMc: Sculpture is a fairly new addition to your range of mediums. What made you want to try it?

SS: It wasn’t a case of, “Oh, today I’m going to start making sculptures.” The work has engaged with history and decolonisation for decades without glorifying the past. In that respect it has been anti-monument in spirit from the beginning. In 2017, I had the opportunity to be part of the New York City Mayoral Advisory Commission on City Art, Monuments and Markers. Hearing differing public opinion, historical reckoning and tensions over historical representations during that process gave me the idea of translating a painting into a sculpture to see what would transpire. The resulting sculpture has allowed a new entry point into my practice, a reorientation around the female protagonists prevalent in the paintings since the mid-90s. Gayatri Gopinath’s essay in the Extraordinary Realities book resurrects my feminist 90s work though a queer lens.

Shahzia Sikander. Promiscuous Intimacies, 2020. Bronze sculpture. Courtesy the Artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, NY, and Pilar Corrias Gallery, London.

AMc: The piece you are talking about, Promiscuous Intimacies (2020), is a bronze sculpture juxtaposing European and Indian ideals of female beauty. It was installed outside for the first time as part of the solo exhibition Unbound, at Jesus College, University of Cambridge.

SS: Exhibiting Promiscuous Intimacies, which speaks on decolonisation from a uniquely female perspective, at the time when Jesus college handed over a looted Benin sculpture to Nigeria was great timing.

The work refers to a truncated temple sculpture of an Indian celestial dancer now residing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The dancer flirtatiously entwines with a figure drawn from the Italian mannerist painting An Allegory with Venus and Cupid by Agnolo Bronzino. By entangling mannerism, the anti-classical impulse within the western tradition, alongside Indian art, both as accomplice and witness of a one-sided history, I was pushing back at the polarising east-west binary while highlighting art history’s classicism and ethnocentric reactions to Indian art as per Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s doctrine. The initial sketches were first created for a 36 foot (11 metre) banner for the Museum of Modern Art in 2000 and were inspired by Partha Mitter’s book Much Maligned Monsters. In 2020, I worked with two dancers to determine the legibility of this extreme posture. In the ensuing sculptural iteration, the protagonists took on new roles. Which of them was in a position of power? Was the Devata unattainable or is the Venus lifting her up? Who wants whose gaze? What is the nature of the relationship? You question one thing, and another thing comes up. It’s open-ended while being extremely precise. I thought out the details with extreme care, for example how Venus’s hand cups the Devata’s foot, the intimacy of that or the tug at the necklace. The choice of the patina colouring, too, created a palette, which draws the figures closer to a geographical-historical relationship between Greece and India and their overlapping history of sculptural traditions.

Shahzia Sikander. Arose, 2020. Glass mosaic, 84 x 60 x 2 in. Collection of Minneapolis Institute of Art. Courtesy the Artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, NY, and Pilar Corrias Gallery, London.

AMc: One work in the Pilar Corrias exhibition was a new glass tesserae painting, Touchstone (2021), inspired by your animation Reckoning (2020). Can you explain what is meant by “glass tesserae painting”? Is it a mosaic? Is there any painting involved, or do you consider a mosaic to be a painting of a kind? How does the work relate to the animation?

SS: I began experimenting with glass and stone mosaic in 2015 on a large scale, a 70-foot permanent public art commission for Princeton University. Glass was a natural direction, as much of my work deals with transparency and light. The mosaics are made from coloured glass and conceived as paintings. What led me to mosaic was animation. It was the dynamism of the pixel that emerged in my mind as a parallel to the unit of a mosaic. With that approach I was keen to explore mosaic as an animated and less static form. The starting point is always a drawing that is built towards animation and simultaneously towards a glass painting. Drawing is my thinking hat. It is a notational tool, a fundamental language that allows me to collaborate with other languages such as writing, animation, mosaic, music and sculpture.

The animated film Reckoning was made from multiple drawings. Reflecting on relationships that embody a moment of reckoning, such as between women and power and human and nature, the work centres around themes of life, death, colonialism, ecology and fertility. A still from Reckoning was used as a point of departure for Touchstone. The centrality of the feminine is a mutual theme in both the works. In Touchstone, it takes on visual prominence as a female character emerging from a dense landscape borrowed from Reckoning, wrought by the inhumane destruction of bodies and land. The female is holding on to a “chalawa” (a Punjabi term for a poltergeist). The gesture for me symbolises the paradox of holding on to something that is uncapturable. The moving, morphing, flowering land emphasises that Earth is not an inert entity where the invisible and the visible world are both animated through the presence of life and death. Both these works are about struggle and conflict, memory and migrancy and meditation on symbols of extraction, with links to nature, to imagination and art as sources of abundance as opposed to the desiccating logic of extraction.

Shahzia Sikander. Kindred, 2021. Ink, water colour and gouache on paper, 244.2 x 153 cm (96 1/8 x 60 1/4 in). Courtesy of the Artist and Pilar Corrias, London.

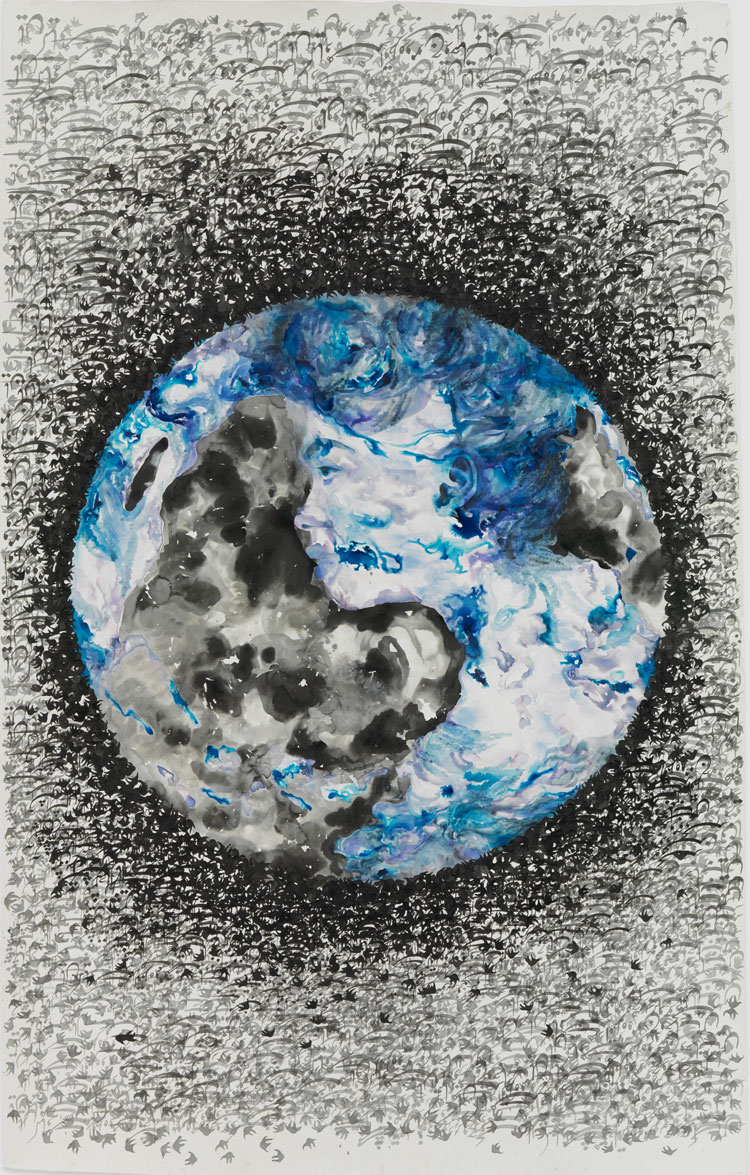

AMc: Another new work in the Pilar Corrias exhibition – a large drawing – depicted a globe, containing a female profile in the shape of an “upside-down” Africa. Tell me more about this piece.

SS: This painting continues with the theme of redemptive powers of the female body as a counter to the extractive forces of global capital. The female face in this work, titled Kindred, hints at Octavia Butler’s novel of that name. It is about women, unison and collective space – from the feminine in nature, as a hope for environmental catastrophe to women as agents of change and nurture with expansive and accommodating abilities. The female face emerged from the ink while I was painting Africa and I was able to use it metaphorically as a symbol of resistance to, and endurance of, the global histories of empire. The notion of the sea, the large oceanic space around the globe, is constructed with Urdu text, built from a phrase from a poem by Ghalib that speaks about the immense and the fragile and their interdependence. The text is upside down intentionally to play with the intersecting illusion of water and writing. The image also has an uncanny resemblance to a satellite image of human clutter in space.

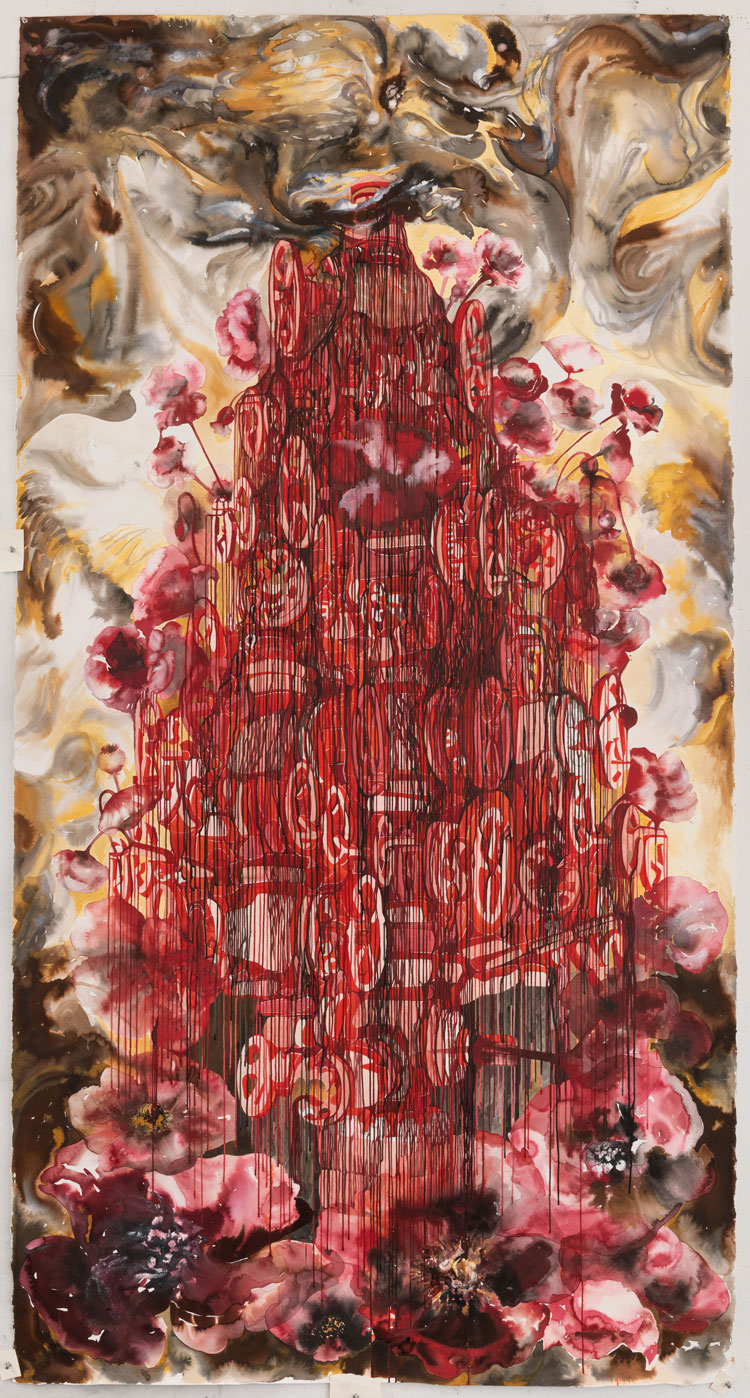

Shahzia Sikander. Oil and Poppies, 2019-20. Ink and gouache on paper, 248.9 x 129.5 cm (98 x 51 in). Courtesy of the Artist and Pilar Corrias, London

AMc: Some of your large-scale paintings are often referred to as “Christmas trees”. Can you explain this?

SS: The idea for this continuing series of “Christmas tree” paintings 2019-present (The Shroud, Oil and Poppies, Flared, Sub Blues, Land of Tears) came about while researching symbols of extraction. I found a photograph of an oil pumping platform called a Christmas tree in a 1962 issue of BP magazine. I was not aware oil rigs were called Christmas trees. I equated the title and its context in BP magazine as ingenious English wit, a comment on the gift-bearing sentiment of the oil rigs. I then went ahead and constructed elaborate “trees” mimicking Christmas trees while using the armature of oil rigs, spools and chains to create an iconic and ironic image that could represent the paradox of the culture of extraction. The various paintings in this series attempt to explore the entangled faultlines of race, class, gender and how they intersect around capitalism, liberty, happiness and despair. The paintings were made in response to the haunting images of wildfires in California and Australia, accidental spillages in oceans around the world, the intimate histories of opium and war in Afghanistan, slash and burn agriculture, the human costs of displacement and pollution. Our ecological condition is a mirror of social conditions: erosion of climate, of borders, rising waters, rising heat, displacement of bodies, an ongoing engine of extraction, with its inherent exploitative violence, whether it’s towards nature or towards women.

When I am working on these large paintings, I work with brush and ink on the wall as well as the floor. The fluid nature of ink as it pools and drips allows me to equate material with matter, movement with time, and time with history. Painting in this way with ink is akin to thinking with drawing. It is a cyclical process. It’s hard to explain. It’s so fluid.

AMc: It seems as if everything you do feeds into something else, which then feeds back into itself, and so on.

SS: Yes. I'm always seeking multiple meanings and myriad associations. At the root is often a trenchant historical idea or form and how can I dislodge it from its precise or narrow definition.

• Unbound is at Jesus College, University of Cambridge, from 16 October 2021 to 18 February 2022

• Extraordinary Realities is at the RISD Museum, Providence, from 12 November 2021 to 30 January 2022, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, from 20 March to 5 June 2022.