Raphael, Study for the Head of an Apostle in the Transfiguration (detail). Private Collection, New York. © Private Collection.

The National Gallery, London

9 April – 31 July 2022

by TOM DENMAN

The exhibition of the work of Raphael (1483-1520) at the National Gallery, London, has three main selling points. First, no exhibition in the UK has celebrated the artist’s entire career. Second, this entirety not only spans the length of his working life, cut short by his sudden death at the age of 37, but it encompasses the extent of his output: as an architect, archaeologist, designer and printmaker as well as draughtsman and painter. Third, the show aims to emphasise the artist’s ability to work with other artists and manoeuvre the politics of patronage with courteous ease. The first two points are palpable in the show’s scope; the third, given that the exhibition focuses almost exclusively on Raphael’s work, is less obvious. Yet it is felt, mainly in his portraits – including three self-portraits – but perhaps also in the clusters of drawings that he used to instruct his assistants in completing his grander commissions.

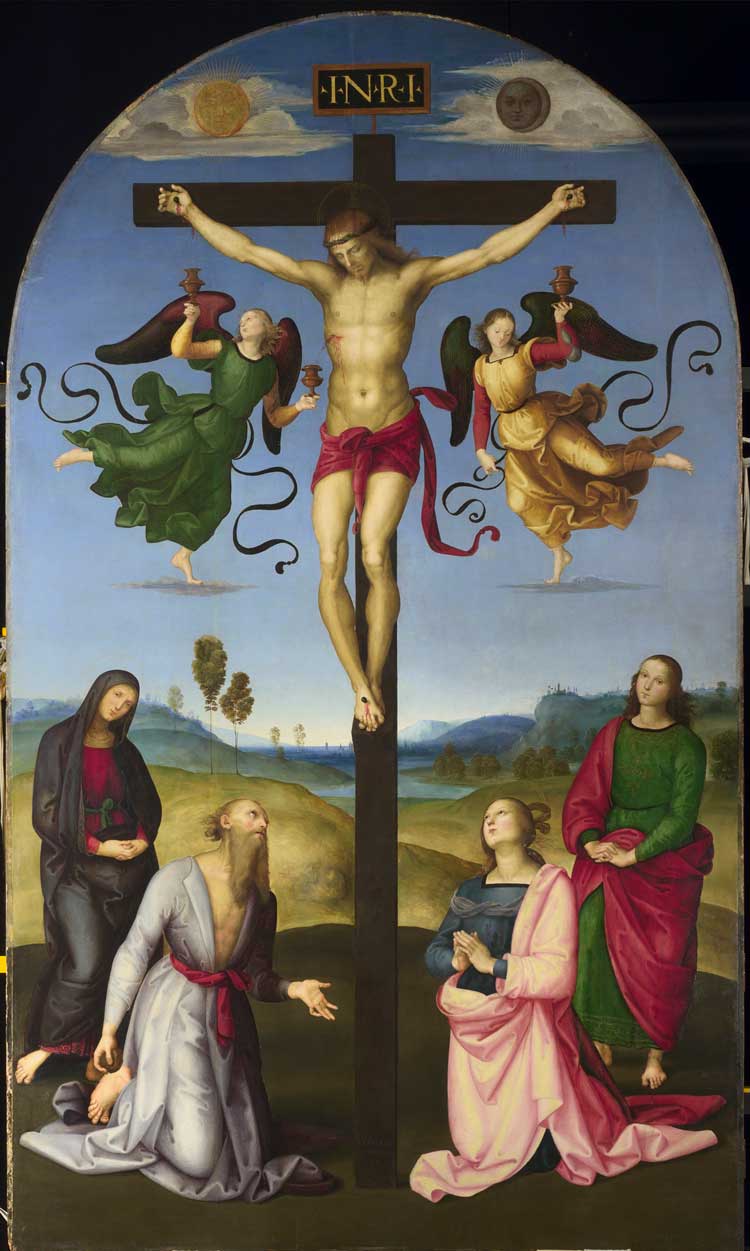

Raphael, The Crucified Christ with the Virgin Mary, Saints and Angels (The Mond Crucifixion), about 1502-3. Oil on poplar, 283.3 x 167.3 cm. © The National Gallery, London.

Raffaello Santi, or Sanzio, was born in Urbino in 1483. He probably received his initial training from his father, Giovanni Santi, a painter favoured by the Duke of Urbino, Federico da Montefeltro, one of 15th-century Italy’s most illustrious patrons. One of Raphael’s earliest drawings, probably a self-portrait (c1498), displays astonishing control in his application of the chalk, hinting at a certain reserve, which reverberates with the youthful temerity of the boy’s expression. The subtlety of Raphael’s wit is revealed in his Saint Sebastian (c1502-03). The saint, who resembles the artist, holds the arrow of his martyrdom as if it were a brush, the hand’s tactility mirrored in the kink in his necklace. Such reciprocity between elements, which Raphael famously mastered in his multi-figural compositions – even in his early attempts to inject variety in symmetry, such as in the The Mond Crucifixion (c1502-03), which dominates the first room – existed also in the minutest of gestures.

Raphael, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, about 1507. Oil on poplar, 72.2 x 55.7 cm. © The National Gallery, London.

From about 1504, Raphael spent an increasing amount of time in Florence, where he learned from Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. Raphael’s drawing (c1505-07) after the Leonardo’s Standing Leda (lost) fed into the corkscrew composition of his Saint Catherine of Alexandria (c1507). Raphael’s copy also exemplifies his early use of pen and ink, the traditional drawing materials of Florence; his drawing of the Annunciation (c1506) stands out, not least for the human expressiveness of the figures – God the Father might even be smiling as he oversees the incarnation. The painted Uffizi Self-Portrait (c1506) dates to this period, and despite its iconic status, retains its powerful nuance. The boy’s insecurity in the earlier drawing has metamorphosed into an embodiment of knowing nonchalance, or sprezzatura, a courtly ideal theorised by his friend Baldassare Castiglione, whose portrait features in the final room.

Raphael, The Virgin and Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist (The Alba Madonna), about 1509–11. Oil on wood transferred to canvas, 94.5 cm diameter. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Andrew W. Mellon Collection (1937.1.24). Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington.

In Florence, Raphael experimented with the circular “tondo” format, used especially in this city for representations of the Virgin and Child. The exhibition includes three examples, through which we witness Raphael playing with different compositions, culminating in the off-centre Alba Madonna (c1509-11). Raphael found endless possibilities for experimentation in even the simplest and most conventional of subjects. In his Madonnas, it is first and foremost the psychological involvement of the figures that endures – conjured in the interplay of gazes, facial expressions, figural compositions and poses, and, above all, in the representation of touch, itself intensified by Raphael’s own painterly tactility. The facial skin contact between mother and child in The Tempi Madonna (c1507-08) signals a seamless ambiguity of emotion worthy of the Mona Lisa, as the Virgin appears to cry, laugh, smile and kiss, her expression responding at once to Christ’s birth, his death and their first embrace after the Resurrection.

Raphael, Portrait of Pope Julius II, 1511. Oil on poplar, 108.7 x 81 cm. © The National Gallery, London.

In 1508, Pope Julius II summoned Raphael to Rome to contribute to the decoration of his apartments in the Vatican. The pope’s fondness for Raphael’s work soon meant that the 25-year-old was charged with frescoing the whole suite. As Arnold Nesselrath explains in his catalogue essay, this monumental task was by no means straightforward, being continually interrupted and reconfigured by the changing demands of its patrons, not to mention the election of a new pope, Leo X, in 1513. This is partly documented by surviving drawings, several of which are shown here, opposite a 1:1-scale digital print of Raphael’s The School of Athens (1509-11) and his radically intimate portrait of Julius II (1511). Of these, a Michelangelesque cartoon of Moses before the Burning Bush (1514), with pinpricks for transferring the image to the ceiling of the Stanza di Eliodoro, is outstanding.

Raphael, An Angel. Pen and brown ink over geometrical indications in blind stylus, 17.9 x 20.6 cm. The Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Raphael was appointed chief architect of the new Saint Peter’s Basilica in 1514, around which time he also began a major archaeological survey of ancient Rome. The exhibition celebrates Raphael’s career as an architect by including drawings such as the ground plan (c1511-12) for the Chigi Chapel at Santa Maria del Popolo and studies for an unrealised villa project (c1516), alongside a “critical-interpretive reconstruction” of the facade of the Palazzo Branconio dell’Aquila (2020), constructed in 1518-21. There is a poignancy here, as we are led to imagine what more Raphael might have achieved in this domain had he lived longer. A standout relic of his archaeological interests is the original draft of a letter from Raphael, written in 1519 with the aid of Castiglione (the expert in courtly manners), to Leo X, in which the artist presents his critical view of ancient Rome. This letter, along with the many drawings interspersed throughout the exhibition, brings out not only the way the artist worked and communicated, but also how he thought.

Raphael, Study for the Head of an Apostle in the Transfiguration. Private Collection, New York. © Private Collection.

The exhibition’s finishes with a display of Raphael’s late portraits, offering an affecting glimpse into his personal life. Even in the portrait of Lorenzo de’ Medici (1518), a sense of the duke’s suave conviviality, as well as a touch of vulnerability, exude from behind his princely costume – as if Raphael knew him, despite the work’s hurried execution and the formality of the commission. The way these figures fill space is almost sculptural, reflecting the lesson of Michelangelo, which by now Raphael has absorbed into his own idiom, working in a genre and with an eye for the individual that, to our knowledge, the former never mastered. The showstoppers are his portrait of Castiglione (1519) and Self-Portrait with Giulio Romano (1519-20). Castiglione’s eyes observe, his ear listens, and yet, although he attends to everything about us, he does not intrude. Somehow, we feel Raphael’s hand on Romano’s shoulder, passing on the baton to his assistant, who points outwards, as if to the future. In addition to being a scholar who knew his Vitruvius and kept abreast of the latest art theory, Raphael was an artist invested in human emotion.

It is a testament to Raphael’s popularity that when he died on Good Friday, 6 April 1520, his fellow artists, friends and patrons – including the pope – were overcome with grief, and to his status that he was entombed in the Pantheon. If I am left in any quandary, it regards his later posthumous reception, especially in Britain, from whose formidably well-stocked collections many of the works here are sourced. It was especially, but by no means exclusively, in Britain that Raphael became an academic standard. This legacy, seemingly celebratory, meant that Raphael’s name became associated with pedanticism, leading to various backlashes, most famously in the foundation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848. Could a revivification of Raphael, counteracting his posthumous academicisation by celebrating (as closely as possible) the artist as he was in his own lifetime, be one of this exhibition’s unspoken goals? Even if undeclared, the goal is achieved.