James Ward, Fanny, A Favourite Dog, 1822 (detail). By courtesy of the Trustees of Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.

The Wallace Collection, London

29 March – 15 October 2023

by ANNA McNAY

Self-branded as #TheCriticWithTheDog, since, wherever I go, my emotional support dog, Parsley, goes as well, I (should I say “we”?) obviously couldn’t miss the Wallace Collection’s exhibition, Portraits of Dogs: From Gainsborough to Hockney (self-branded as #WallaceWoofs). We were given special early access, just as the installation was being completed, and nearly the whole Wallace team came down to check out their most discerning critic’s judgment. As it was, Mr P remained largely inscrutable (I did shield him from the two specimens of taxidermy), but I understood his overall opinion to be one of approval.

Among those who came to greet us was Xavier Bray, director of the Wallace Collection. Clearly a dog man, he explained that the idea for this exhibition arose through thinking about the number of contemporary artists with dogs in their studios, as muses and/or companions, and, from that, looking back through the history of artists with dogs and finding it to be a partnership as old as time. The show, like so many, was delayed due to the pandemic, but, if anything, it will appeal to an even greater audience now, with dogs having proven such loyal companions during the lockdowns, and with so many households having added one to their family during this time. In fact, I learn from the comprehensive catalogue accompanying the exhibition that one in three homes across Europe and North America houses at least one dog.

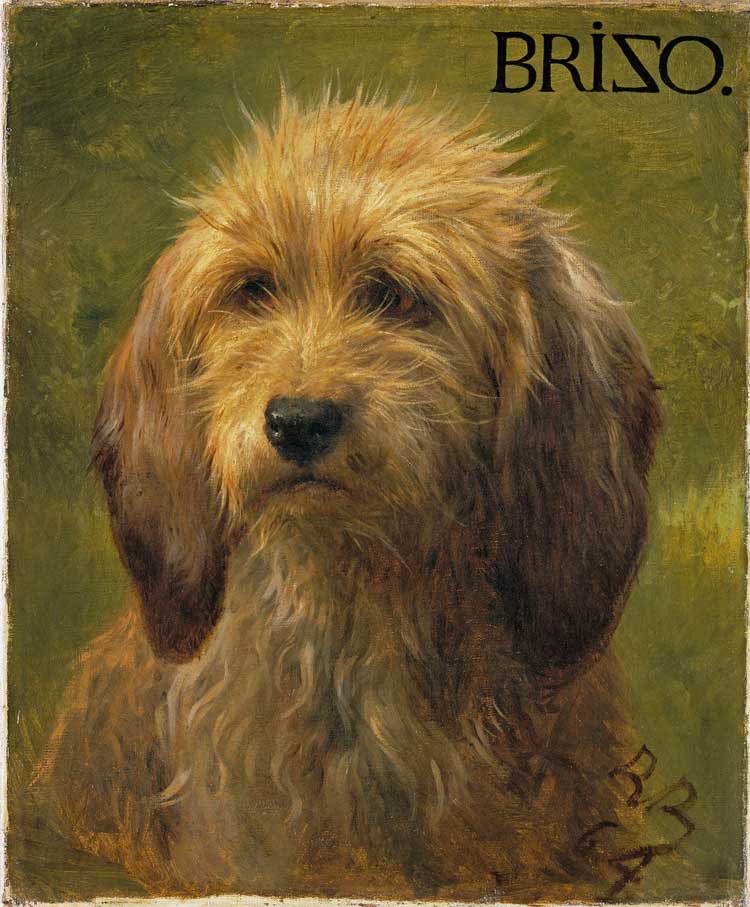

Rosa Bonheur, Brizo, A Shepherd's Dog, 1864. © The Trustees of The Wallace Collection.

The Wallace Collection is, of course, the perfect host for such an exhibition, since two of its most popular paintings are of dogs: 19th-century French animalière Rosa Bonheur’s personable Brizo, A Shepherd’s Dog (1864) and Edwin Landseer’s allegorical Doubtful Crumbs (1858-59). Overall, the collection boasts depictions of 907 dogs, of more than 15 different breeds, among its paintings, sculptures, medals, jewellery, arms and armour.

Edwin Landseer, Doubtful Crumbs, 1858-59. © The Trustees of The Wallace Collection.

Dogs have, assuredly, appeared in paintings and portraits for centuries. They are represented alongside humans in the earliest cave paintings. Titian, Van Dyck and Rembrandt, to name but a few masters, were all aware of the symbolic value they possess and how this might be used iconographically in a composition. Since the Renaissance, they have been seen as symbols of loyalty, as well as serving to highlight high social status and wealth. This exhibition includes only portraits of dogs on their own, independent of their owners, however. Additionally, all the works belong to British public and private collections, emphasising the extent to which this nation, more than any other, has long collected and commissioned portraits of man’s best friend.

Unsurprisingly, many of the greatest dog portraits belong to the Royal Collection, and the naive but loving and endearing pencil and watercolour sketches made by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert are real stars of this show. The royal couple took drawing and etching lessons from Landseer during the 1840s, primarily so as to be able to make likenesses of their canine family, of which Victoria was keen to visually document each member, just as much as any prince or princess. Landseer himself painted more than a dozen portraits of royal pets, mainly dogs, under Victoria’s patronage, and the one on loan here, of her especial favourite, the King Charles spaniel Dash, was his first. He absolutely captures the animal’s furrowed brow and intent gaze, his soft curls of fur and his glistening wet nose.

Unknown artist, Roman, The Townley Greyhounds, 1st-2nd century CE. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The subtitle of the exhibition is perhaps a little misguided, as several exhibits precede Gainsborough by many centuries. The earliest work on display is a marble sculpture of a pair of greyhounds, depicted tenderly with the bitch nibbling the other’s ear, dating from first-century Roman times. There is also a beautifully delicate and anatomically meticulous page of sketches of a dog’s paw by Leonardo da Vinci, in his recognisable left-handed crosshatching. A Dog Lying on a Ledge, by an unknown artist thought to be Genoese or Spanish, also pre-dates Gainsborough, painted somewhere between 1650-80. When I first looked at it, I saw a peacefully slumbering hound, resting in the sun. So did Bray, he says, until a professor of veterinary science, whom he asked to look at it, maintained that the dog’s glassy eyes and lolling tongue meant he had died from dumb rabies. It is difficult to see the poor creature in the same way once that thought has been put in mind.

James Ward, Fanny, A Favourite Dog, 1822. By courtesy of the Trustees of Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.

Bray, however, stands by his association of the dog with the philosopher Diogenes, who believed human beings live their lives artificially and hypocritically and would do well to study the ways of the dog. This is, in fact, the subject of another of Landseer’s allegorical paintings on show, Alexander and Diogenes (c1848). Diogenes was a cynic, a term that derives from the Ancient Greek κυνικός (kynikos), meaning “dog-like”. The philosopher was proud to be thus known, saying: “[Like a dog] I fawn on those who give me anything, I bark at those who refuse, and I set my teeth in rascals.”

Thomas Gainsborough, Tristram and Fox, c1775-85. © Tate Images.

Despite being named in the title, there is only one work by Gainsborough in the exhibition: a loan from Tate of his dogs Tristram and Fox (c1775-85). Especially lovely in this painting is Fox’s cheeky underbite. Also, despite the name-check, it is generally considered to be Gainsborough’s contemporary George Stubbs who elevated the painting of dogs to academic status in this country. Although perhaps better known now for his equine works, in his lifetime he exhibited more paintings of dogs at the Royal Academy than he did of horses. One of four works by him included here is of a Maltese terrier, stretched out in a perfect “downward dog”, eyes peering out from beneath her long fringe. Despite the 18th-century vogue for lapdogs, very few English portraits of them survive. In this one, at least, be the fashionable haircut as it may, she at least remains “dog-like”, unlike the pitiable subject of Dog of the Havana Breed (1768), by Jean-Jacques Bachelier, which sits trussed up and begging, shaven to a naked pink over most of her body, with crimped white fur forming a cape around her shoulders, and her long fringe held back by a ghastly pink ribbon.

Jean-Jacques Bachelier, Dog of the Havana Breed, 1768. © The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle.

Nothing can surpass Minnie the Lulu Terrier (c1883) in terms of ostentation, however. This vulgar (at least by present-day standards) taxidermy specimen is displayed in an ornately decorated glass case, as if she were a holy relic. At the time, this was the superlative in dog veneration. Frankly, it makes me wince. A fellow stuffed creature, the Pekinese dog Ah Cum, was one of the first of his breed introduced to Britain in 1896 and is accordingly credited with being “the grandfather of all Pekinese in Britain”. At the very least, this incredible thought makes one realise how many dog breeds derive from our early foreign trade. Even the common labrador bears a name meaning “working dog” in its country of origin, Spain.

Edwin Landseer, Hector, Nero and Dash with the Parrot Lory, 1838. Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023.

Dog portraiture, as a genre, developed alongside human portraiture, and while Landseer painted commissions of Queen Victoria’s pets, he also made a great number of allegorical works (including Alexander and Diogenes, already mentioned) and was well enough versed in classical history to select stories to suit his various canine models. In Trial by Jury or Laying Down the Law (c1840), he uses the individual characters of different breeds to satirise members of the legal profession. The white poodle, for example, with its long ears resembling a peruke, parodies the grandiloquence of a judge. The Blenheim spaniel as cub reporter was a later addition for the sixth Duke of Devonshire, who had acquired the work and wished for his own dog to be immortalised. In Dignity and Impudence (1839), on the other hand, the composition is a pastiche of the Dutch portraiture tradition, in which the subject is framed by a window (here, a kennel), with an arm or hand (here, a paw) extending over the edge. While this anthropomorphising of dogs was enjoyed at the time, and is certainly not absent in our modern-day culture, I confess to finding both His Comical Dogs (1836), with the pups dressed up in a tam-o’-shanter cap and bonnet, and A Jack in Office (mid-19th century), where the old hound is smoking a pipe, more than a little too twee.

Charles Burton Barber, Minna, c1873. Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023.

Moving into the 20th century, there are a couple of heartfelt paintings by Lucian Freud. He acquired his whippet, Pluto, in 1988, and made an etching and a painting of her as a pup that same year, the latter of which is included here, showing her asleep with her front paws casually crossed, different tones shaping her lean contours, and scratches into the surface of the paint (with the end of the brush?) highlighting the wave of her seal-like fur. Known for his human subjects, which comprise the most part of his body of work, Freud, in an interview in 2002, said: “I like people to look as natural and physically at ease as animals, as Pluto my whippet.” Clearly a devoted dog-parent, he made another painting, in 2003, showing a simple grave marker amid mulched autumn leaves: a searing and poignant statement as to the pain and magnitude of the loss of a dog.

The agony of loss is shown to work both ways, too, once more by Landseer, in his affectionate painting The Old Shepherd’s Chief Mourner (c1837), in which the dog holds a vigil by his master’s bedside, resting his chin tenderly on the blanket. (I have to say, this utterly lovable habit of perching the chin is one of my favourites in Parsley’s repertoire.) Additionally, in this moving section on death, there are several intricate brooches and cravat pins, some with portraits of the deceased pets, and some also with a lock of fur.

David Hockney, Dog Painting 19, 1995. © David Hockney. Photo: Richard Schmidt Collection / The David Hockney Foundation.

The most contemporary inclusion in the exhibition is a room of paintings by David Hockney of his dachshunds, Stanley and Boodgie, made over a two-year period beginning in 1994. Hockney set up easels at different heights around his house, with canvas and palette at the ready, so he could take his place and make a speedy sketch, whenever his duo of muses took position. The result is a wonderful array of lovable and cheeky snapshots, capturing the truth in the statement: “It’s a dog’s life.” Of his project, Hockney wrote: “I make no apologies for the apparent subject matter … these two dear little creatures are my friends … They’re like little people to me. The subject wasn’t dogs but my love of the little creatures.”

So, is this exhibition just an excuse for kitsch sentimentality? You might argue I am biased, but, equally, I could, as an art historian, take this negative stance. I won’t, though, for much as this is a show that will make you smile, and perhaps even utter an “awww”, it is also well researched and curated, and it explores a relationship significant in so many artists’ and patrons’ – and, indeed, visitors’ – lives. With Hockney also speaking on the audio guide, a second audio guide, with paw prints as markers, specifically for children, and drawing activities based on Hockney also available, there is certainly the expectation that this will appeal as a family exhibition, and hopefully this will prove to be the case. If it can act as an introduction to art for those who might not otherwise feel a connection, this is surely a good thing. It’s just a shame that Parsley will be the only canine family member who gets to tag along.