by JANET McKENZIE

Peter Hill was born in Glasgow in 1953 to a Scottish father and an Australian mother. He grew up in Scotland, but has lived in Australia since 1988, when he first arrived on a British Council lecture tour. He now divides his time between Scotland and Australia, and is a committed European globalist. After training at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art for two years, he left in 1973 to become a lighthouse keeper on the tiny remote island of Pladda off the west coast of Scotland, and later at Ailsa Craig and Hyskeir in the Outer Hebrides. His experience of a way of life that no longer exists has informed his worldview. In his nomadic life, he spends a great deal of time in big cities – Sydney, New York, Paris, Singapore and London – but prefers to base himself in smaller centres – Hobart, Geelong, Glasgow, Bramhall and Longniddry.

In 2003, he published his coming of age memoir of his youth and innocence, Stargazing: Memoirs of a Young Lighthouse Keeper, reflecting a lost way of life and new possibilities for future societies.

After the lighthouse experience, Hill returned to art school at Guildford in England. Within a few weeks of starting his course, he was almost blown up in the Guildford pub bombings, in which five people died, and he lived with the trauma of that for many years. It is this trauma that is often disguised (or camouflaged) through a veneer of humour within what he calls his Superfictions, hybrid artworks that exist in the gap between installation art and literary fiction. Hill studied for eight years around London before returning to Scotland, where he began writing about Scottish and international art for Art Monthly, Studio International, Design and Artscribe.

A year at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris led to a teaching position at Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen. He also set up the Scottish art magazine Alba, which ran for six years. A quirky humour and absurdity runs through much of Hill’s writing and art practice. The irreverence and wit of the Belgian artist and poet Marcel Broodthaers (1924-76) can be identified in Hill’s Fake News + Superfictions (fakenewsandsuperfictions@gmail.com).

Peter Hill, The Hermann Nitsch Shower Curtain, 1988 - ongoing. With pop-up Performance by Michael Vale as The Smoking Dog, at Margaret Lawrence Gallery (VCA) Melbourne

during opening night of Peter Hill’s 25 year retrospective Desire Paths to a Fictional World, March, 2012.

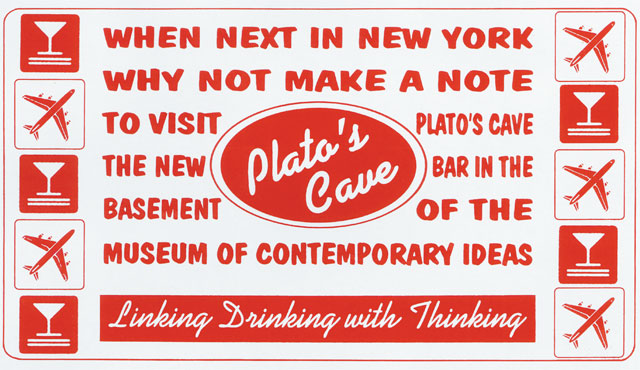

Hill explains: “I invented the Superfiction both as an artwork and as a way of testing ideas and expanding the notion of ‘lateral thinking’. Much of this comes from the philosophy of science and Karl Popper’s ideas about ‘falsificationism’, alongside Thomas Kuhn’s definition of ‘paradigm change’ in his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions and the synthesis of these ideas in Against Method, an anarchistic theory of knowledge by Paul Feyerabend (who described himself as a dadaist). In 1989, I created the fictitious Museum of Contemporary Ideas, which existed only through its press office. Supposedly the biggest new museum in the world, it was written about in Germany and Austria in Wolkenkratzer magazine as if it were real, and a meeting of German industrialists and curators was held to see if Frankfurt could build a real museum based on this model.”

Studio International met Hill in Edinburgh as part of his two-year international lecture tour: Fake News + Superfictions (2017-19), which turns the idea of a lecture tour into an artwork.

Janet McKenzie: When did you first conceive of your Superfictions projects, the first being your Museum of Contemporary Ideas, notionally on New York’s Park Avenue?

Peter Hill: My original plan was not to create a fictional museum at all. Back around 1986, I wanted to create a fictitious art magazine – New Stuff magazine was its working title. It would be an expanded version of my art school thesis in Farnham when, in 1976, I invented nine or 10 fictitious artists and groups and set them 10 years into the future.

I would interview all the different artists featured in the magazine, under the guise of various fictional critics and art writers, and I would also make the artworks – paintings, sculptures, photographs, videos, installations – by the different male and female artists. In a sense, some, but not all, of the final artworks would not be as important as the photographic evidence of their existence, as printed on the pages of the magazine. They would be like props in a film. However, I wanted it to look as good in terms of production values as Artforum or Flash Art magazine, which was becoming glossy at that time. But I was having enough problems – especially with the vagaries of advertising – keeping ALBA a real but low-budget magazine, alive, without the stress of launching a bigger, glossier, fictional version. So I put the whole idea on the back burner and lived out the fantasy in my head.

Peter Hill, Plato's Cave in the basement of the Museum of Contemporary Ideas.

A few years later, the solution to the problem came after a restless night’s sleep. I woke up one morning in 1989, in my little flat in Leith, and suddenly realised that, for a very small financial outlay, I could create a fictional museum – and why not the biggest new museum in the world? – through its imaginary press office. For the past few years, running ALBA, I had been receiving hefty press releases from the likes of the Pompidou Centre, the Tate Gallery, Museum Ludwig in Cologne, the Metropolitan Museum, the National Gallery in Canberra, and many others. Without exception, they were all printed on A4 paper with “spot colour” – that is, only one colour plus black and white – so were very cheap to reproduce. Some of these real press releases would run to more than 10 pages and cover more than events and exhibitions.

Most were very dull to look at, and even duller to read, with lazy grammar and syntax. I also noticed that the bigger the museum and the more press releases it sent out, the grainier the images were, as they had gone through the photocopier so many times. So I tried to reproduce this – in a trompe l’oeil sort of way, and many superfictions I have come across, I describe as “neo-trompe l’oeil” – by giving my press releases all of those negative characteristics. I would put the original mastercopies through the photocopier many times to deliberately degrade the images. And this led to my interest in “the migration of images”, and how a reproduced artwork can go through many subtle or overt changes while remaining essentially the same.

A photograph I took of Hermann Nitsch, in front of his “rivers of blood” installation, at Nick Waterlow’s Bicentenary Biennale in Sydney in 1988, is a good example of this. It eventually became The Hermann Nitsch Shower Curtain– an “assisted readymade”.

JMcK: You have just returned from Brussels, where you saw, Magritte, Broodthaers & Contemporary Art, at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts, Belgium [which continues until 18 February 2018]. What was your experience of the exhibition?

PH: I loved it. It was one of the great art experiences I have had, alongside seeing Philip Guston and the Poets in Venice last year, and Cy Twombly at the Pompidou.

There is a recent, interesting, curatorial turn, pairing two artists alongside each other, for example Andy Warhol and Ai Weiwei at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne; Salvador Dalí and Marcel Duchamp, currently at London’s Royal Academy of Arts; Tracey Emin with Louise Bourgeois. Often very tenuous connections are drawn. With Magritte and Broodthaers, there was tangible evidence of their shared obsessions and their fellow feeling for each other. An added bonus was the final section of the exhibition including contemporary and modern artists who had been influenced by them: Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Martin Kippenberger, Ed Ruscha, Joseph Kosuth, Barbara Kruger, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, On Kawara, Robert Gober, Vija Celmins, Leo Copers and Arman.

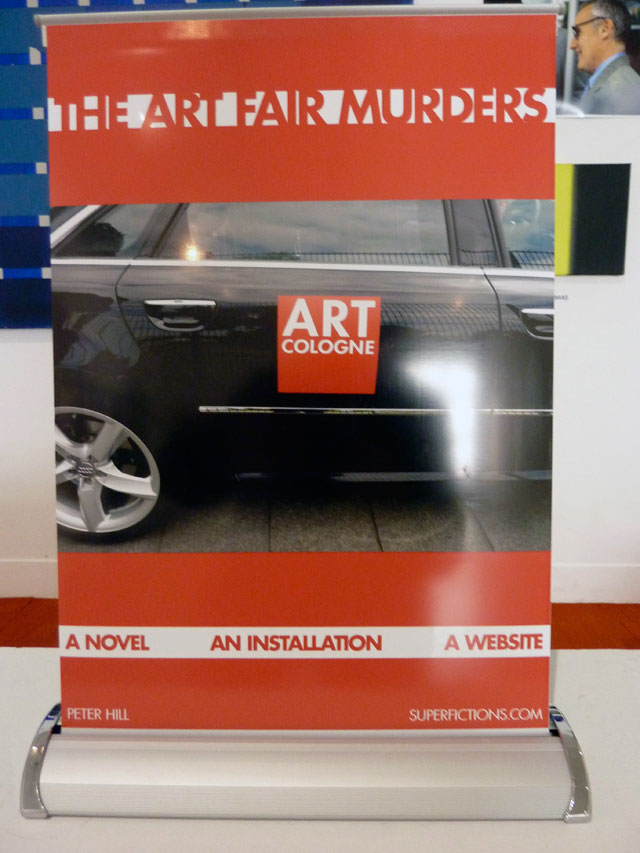

Peter Hill, The Art Fair Murders, 1994 on-going. Detail of installation, 2012, dimensions variable.

JMcK: You first encountered Broodthaers’s work in Studio International while you were still at school, and have referred to Rosalind Krauss’s writing on his importance. What do you identify his unique contribution to ongoing conceptual dialogues to be?

PH: Rosalind Krauss’s A Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition was named after a work by Broodthaers, and centres on Broodthaers’ passion for breaking down barriers between disciplines. He was a poet who became an artist, and launched his second career through what he called an “insincere” gesture – while today’s zeitgeist is for “authenticity”, an interesting contrast. For his first “insincere” artwork, he encased his final book of poetry into a block of cement – perhaps one of the first works of “concrete poetry”? And with his fictional Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles (1968), which he installed in – some say – as many as 11 museums and galleries before his death, he arguably singlehandedly created the phenomenon of installation art. This is partly why he is so important today to a range of artists, from Cornelia Parker and William Kentridge to Peter Fischli.

JMcK: I know you never met Broodthaers. But which of the many artists you have met and interviewed most excited you in relation to your own work?

PH: I met and interviewed Ian Hamilton Finlay and the situationist Ralph Rumney. In fact, I brought them together and still have an unpublished interview between them. I followed Ian’s battles with the Hamilton authorities over rates on a monthly basis for Art Monthly in London over three issues, and I was there at Little Sparta when a group of Saint-Just Vigilantes signed a document to the United Nations asking for peacekeeping troops to be parachuted in to Little Sparta. Around that time, Michael Spens, then editor of Studio International, asked me to interview Ian for the magazine. Ralph – who was married to Peggy Guggenheim’s daughter Pegeen, who tragically took her own life – was one of the original members of the situationists. Some dispute this. He is not in the original photograph taken at Cosio di Arroscia, but that is because he took the photograph and in doing so wrote himself out of history. Ian rarely stepped outside Little Sparta because of what he described to me as his “nervous condition”, while Ralph had no home of his own but travelled constantly – the original psychogeographer and couch-surfer.

Peter Hill working as the fictitious painters Herb Sherman and Hal Jones from his Superfiction

The Art Fair Murders, Aesthetic Vandalism, 2014, 200 x 100 cm.

I am writing an essay that might be expanded into a short book, titled affectionately The Nomad and the Hermit, with Ralph as the nomad and Ian as the hermit. Each reflects a different aspect of my own psyche, with my love for the solitude of lighthouses at one extreme and the energy of Chicago or Berlin at the other.

I must also add the very first artist I interviewed, in 1980, Ian Breakwell and his The Walking Man Diary, which predated Sophie Calle’s Please Follow Me in so many ways. He was such an important artist – yet so disinterested in “importance”.

JMcK: Lucy Lippard’s book The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society has been popular with artists such as Arthur Watson and Will Maclean, here in Scotland. Have you been influenced by her ideas?

PH: It is a very influential book. It ranges across, history, geography and cultural studies. She is a very significant thinker. I put my own thoughts down on the local and the global in Local Heroes, a long essay for Artscribe magazine in 1983. It focused mostly on practising artists and how they move around the planet, fusing the local with the changing scene of period styles, whether the trans avant garde of Achille Bonito Oliva or the long-overdue appreciation of women’s art and art from ethnic minorities. It contained at least one image of Steven Campbell’s whose work I had reviewed in a previous edition of Artscribe, before Steven moved from Glasgow to the Pratt Institute in New York. The essay was very much about how most of the great artists we associate with Paris, New York, Florence, London and Berlin, were, in fact, born in the provinces and moved to the big cities to study and to flourish. In it, I also mentioned Australia’s Angry Penguins, the Foksal Gallery in Poland, the Singapore Alpha Group, and the artists of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), from Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and the Philippines. In 1981, I visited the Huxian Peasant Painters commune and the Xi’an Academy of Fine Arts, where I and fellow western art students debated concepts of “the local” with students and staff. Later that year, I visited the Anak Alam artists’ commune in Kuala Lumpur, and, when I returned to Glasgow, I became involved in WASPS (Workshop and Artist Studio Provisions Scotland). My best mates there were Alastair Maghee, Alastair Strachan and Dave Lindley. They and others were dynamically involved in setting up what would become the Transmission Gallery. They asked me to become a board member, but I said I would be of more use to them writing about exhibitions at Transmission for various magazines, which I did, with no conflict of interest. But I helped to clear out the old building, sat in on meetings, and in those days we even looked at portfolios of artists who applied to join.

Peter Hill, The Museum of Doubt, 2015. Zeppelin Projects, Brunswick, 2015. Installation, dimensions variable.

JMcK: What are you planning to work on after your current lecture tour, Fake News and Superfictions?

PH: I have had a number of exhibitions in Australia in recent years. I want to extend these projects and develop them in greater depth. There was the Museum of Doubt that I created at Zeppelin Projects in Brunswick. That was the first time I had used a professional sign-writer Tracey Armstrong to write the great text of doubt, “To Be or Not to Be”, on the gallery’s street-level window on the opening night. The whole exhibition was a comment against the kind of Trumpian “certainty” that we have been force-fed in recent years. For me, “doubt” and “faith” are both good and exist on the same side of the same coin. On the opposite side, we have “certainty”, which always seems to lead to war and destruction.

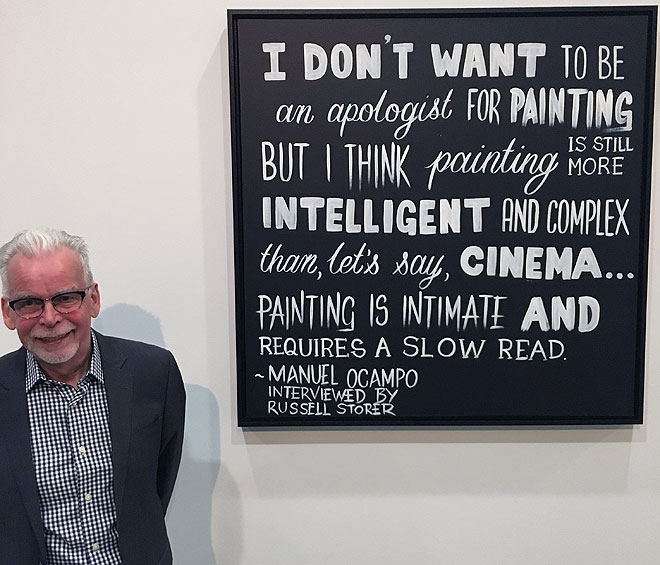

I also want to work on a series of text-based paintings, white on black, about the condition of painting. And I have several projects on how to “make Superfictions real”, using Superfiction strategies to launch real events. These include a “Paintforum International”, from an exhibition I had at the Blindside Gallery in Melbourne – notionally the paintings world’s equivalent of Skulptur Projekte Münster, but happening every year in a different city; the establishment of a Pacific Rim “City of Culture”, based on the European model; and a project involving art and ecology.

While I am travelling on this two-year lecture tour, doing residencies and attending book festivals and biennales, I am also working in trains, planes and hotel bedrooms on a book of interviews with 50 contemporary artists, and a book of collected art writings.

Finally, I am exploring ideas of what I call “Adventurism” that relates to my own work but also to some very exciting younger artists: Robert Zhao Renhui in Singapore with his fictitious Institute of Critical Zoologists; the French artist Mathieu Briand, now living in Port Melbourne, whose huge installation at the Museum of Old and New Art in Tasmania (Mona) grew from his great creative adventure on a small island off Madagascar; and Michael Candy, who in 2016 made his Digital Empathy Device and got through police barricades in Paris’s Place de la République and fixed it to the back of the Goddess of Liberty’s head. This small robotic device is connected to a live website that monitors casualties and bombing raids in Syria. When a bomb explodes in Syria, the device dispenses “tears” so that the statue appears to weep. This work moved me more than any other artwork that year.