John Lyons, Mama Look A Mas Passin, 1990 (detail). Oil on canvas. Courtesy the artist.

Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge

12 November 2022 – 19 February 2023

by BETH WILLIAMSON

The history of Carnival is a rich one, replete with themes of street parades and dance, folklore, flora and fauna. In this exhibition, the work of 28 artists over the space of five centuries engages with the rituals and celebrations of Carnival and all that entails. Three contemporary artists – Paul Dash (b1946, Barbados), Errol Lloyd (b1943, Jamaica) and John Lyons (b1933, Trinidad) – show their work alongside the work of other artists they have selected from the collections at Kettle’s Yard and the Fitzwilliam Museum. In an eclectic display that includes work by Albrecht Dürer, David Bomberg, Pieter Brueghel the Younger and Helen Frankenthaler, Dash, Lloyd and Lyons explore the spirit of Carnival in myriad ways.

,-Whip-Snake,-2004.jpg)

John Lyons, Whip Snake, 2004. Woodcut. Courtesy the artist.

The exhibition’s title references The Mighty Swallow, the performance name of calypso musician Rupert Philo, whose performances were protests against the inequalities imposed on enslaved Africans and other populations under colonial rule. Contemporary Carnival celebrations still reference these cultures, with outdoor processions symbolising freedom and belonging. The exhibition also references The Carnival Trilogy novels by the Guyanese writer Wilson Harris (1921-2018) for whom Carnival is celebratory while simultaneously holding those wide-ranging histories at its core. It is that double-edged sword of celebration and difficult histories that is at the heart of this exhibition, too. There may be joy and festivities in the scenes of Lloyd’s Notting Hill Carnival – Olmec (2001) or Paul Dash’s Bacchanal Drawing (2015-22), but there is pain and violence, too, in images such as Lyons’ Eloi! Eloi! (Lama Sabachtini) (1979) or Whip Snake (2004). That is precisely what this exhibition brings to the forefront of Carnival’s story, taking us beyond the song, dance and procession of Notting Hill Gate and reminding us of its more complex histories.

,-eloi-Eloi-(Lama-Sabachtini),-1976.jpg)

John Lyons, Eloi! Eloi! (Lama Sabachtini), 1979. Oil on canvas. Courtesy the artist.

The cultural and political activist Michael La Rose has said: “Carnival is where Africa and Europe met in the cauldron of the Caribbean slave system to produce a new festival for the world.” This is why the exhibition includes works that show European festivals with a historic connection to Carnival. Whether it is the festival of Sham El-Nessim in Ancient Egypt, or the Bacchanalia of Rome, or the Christian festivals around Ash Wednesday, they are all represented here in one form or another.

Albrecht Dürer, The Torch Dance at Augsburg or The Masquerade. 16th Century, woodcut print from The Freydal Woodcuts series. Image: © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

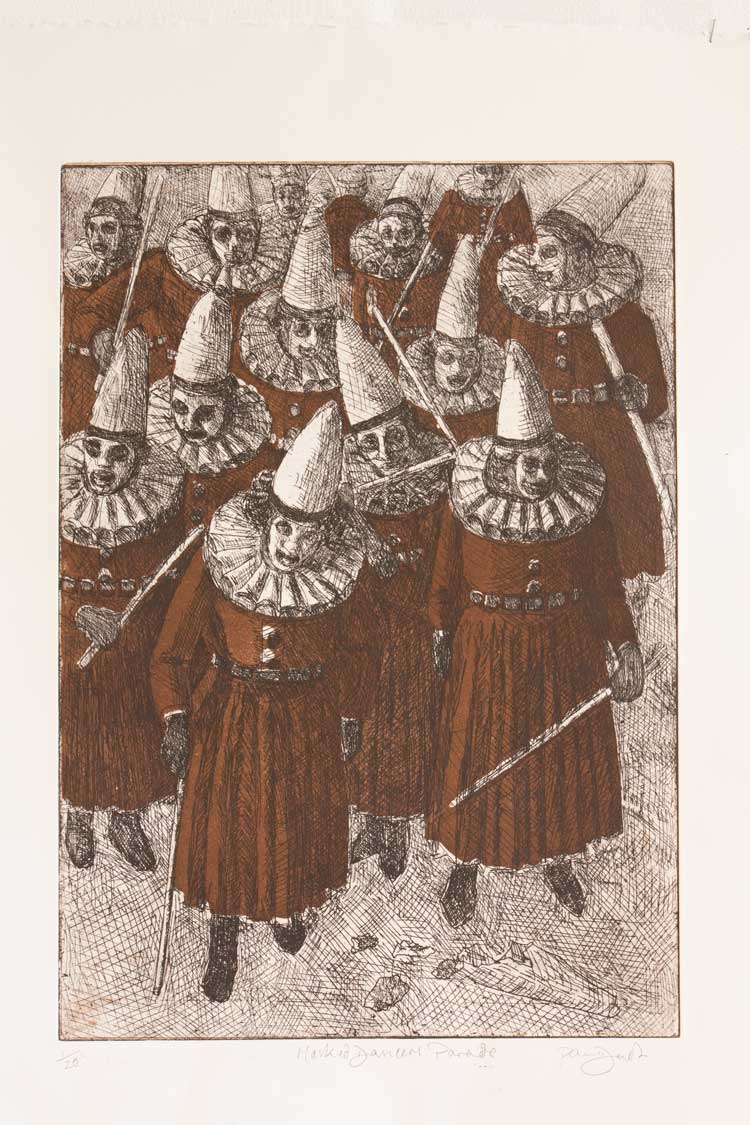

Alongside Dash’s work is shown, for instance, Dance of the Fauns and Bacchantes, an etching by Agostino Veneziano (1490-1540), and Durer’s 16th-century etching The Torch Dance at Augsburg, showing festivities centuries before Dash’s works such as the disturbing Masked Stick-Lick Fighters Parade (2019). The figures’ incongruous dress, Dash explains, gestures to Elizabethan ruffs and a time when African peoples where enslaved by Europeans, and also hints of the Ku Klux Klan and a more recent history.

Paul Dash, Masked Stick-lick Fighters Parade, 2019. Etching. Courtesy the artist.

The layers of reference continue with the dunce’s hat, masks, and the Stick-Lick martial art that developed in the Caribbean plantations during enslavement and colonialism. The distinctly menacing figures in this etching by Dash, replete with historical refence, are in direct contrast to the muted but joyfully colourful tone of his mixed media works, such as Night Revellers Gather for the Parade (2016), Dancing Through the Night (2022), Carnival Dancers Mingle (2019-20), or Bacchanal (2022). Dash calls Carnival “a treat for the senses” and these works convey that in immeasurable ways. Still, as can be seen in other works, such as Carnival Troupe Pays Homage to the Ancestors (2018-19), these works never forget their histories.

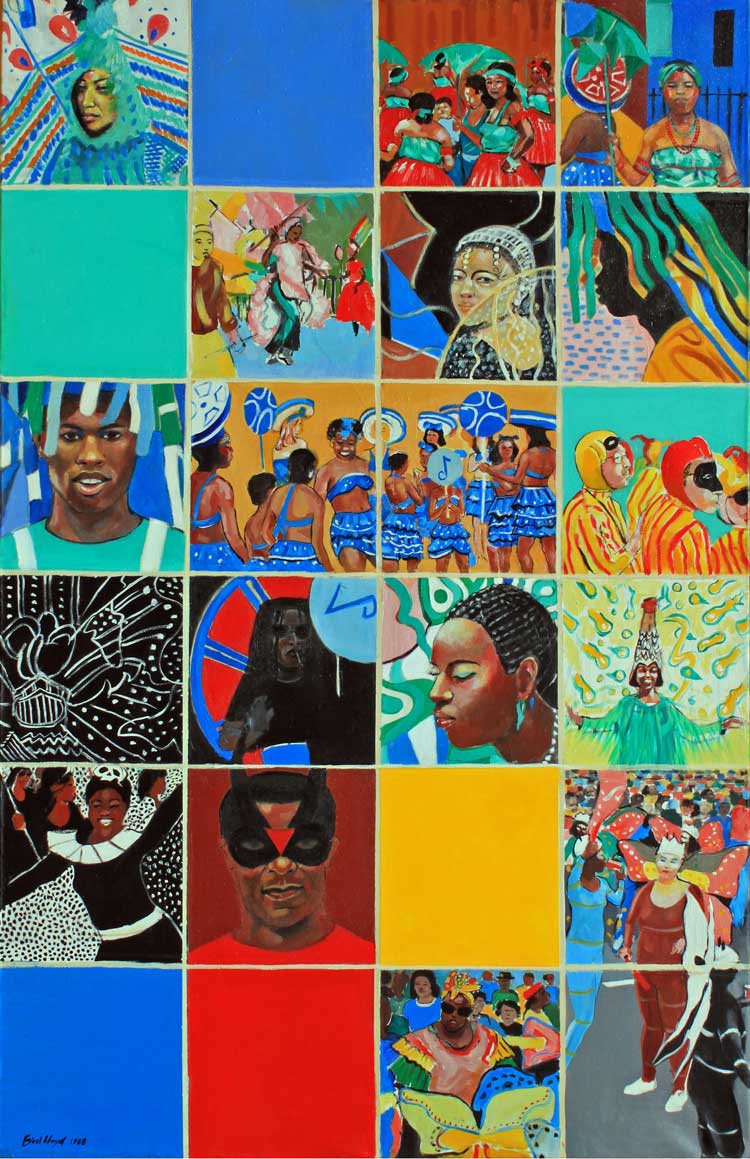

Errol Lloyd, Notting Hill Carnival IIC, 1988. Oil on canvas. Courtesy the artist.

Lloyd’s images of Carnival are rather different. He uses photography to capture images of the Notting Hill Carnival, then translates them into paintings. Notting Hill Carnival IIC (1988) is a chequerboard of 24 images that focus on costume and masks. For Lloyd: “Masked figures are part of the very heart of Carnival, giving the wearer a degree of anonymity, allowing for freedom from normal social, and even, moral constraints, sometimes representing sinister characters that form part of the rich tapestry of Carnival.”

Graham Vivian Sutherland, The Deposition, 1946. Oil on millboard, 152 x 121.9 cm. © The estate of Graham Sutherland. Image credit: © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

The tiny Notting Hill Carnival – Mask (2001) shows a single head and shoulders with a red top and black mask. The horn-like protrusions on the mask might have made the figure intimidating, but the relaxed demeanour and fluid background mean it conveys a sense of freedom more than anything else. Still, the tension between frightening and freedom are underlined by the painting’s position close to two others – Graham Sutherland’s terrifying Tree, Red Ground (1962) and Frankenthaler’s joyous Abstract (c1960-1) – and the conundrum of Carnival emerges once again. On the opposite wall, Lyons’ Eloi! Eloi! is hung close to Sutherland’s The Deposition (1946) and Bomberg’s The Virgin of Peace in Procession through the Streets of Ronda, Holy Week (1935). It is an extremely powerful juxtaposition.

In another astounding pairing, Lyons’ woodcut Whip Snake (2004) hangs next to Picasso’s Minotaure Aveugle Guidé par Marie-Thérèse dans une Nuit Étoilée (1934), the latter selected from the collection at the Fitzwilliam Museum. Such juxtapositions are instrumental in showing how historic and contemporary works can act as touchpoints for new understanding of both, and that is what is at the heart of this exhibition. Dash, Lloyd and Lyons have selected paintings and works on paper from Kettles Yard and the Fitzwilliam to hang alongside their own work. In doing so, the visual conversations initiated in the gallery spaces enable fresh understanding of Carnival and its complex histories for anyone who cares to look.