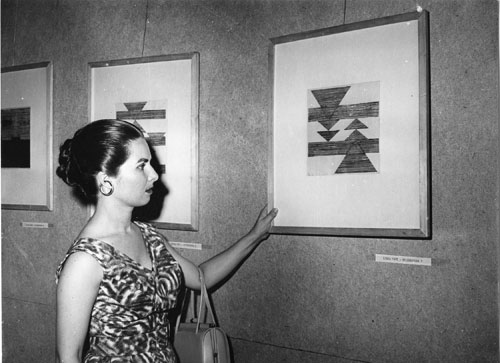

Lygia Pape at the National Exhibition of Concrete Art, 1956. Published in Cruzeiro magazine. Vintage photography. Projeto Lygia Pape. © Projeto Lygia Pape

Lygia Pape – Magnetized Space

7 December 2011–19 February 2012

Serpentine Gallery, London

by CAROLINE MENEZES

Bearing in mind that the artist was a visionary since the very beginning, due to a diversified and long lasting lifework that permeated crucial moments of Latin American art, Pape went beyond the transformation of visual art language and provoked a radical change in the art experience. Recently, the European public has been able to have a taste of her unique production with an exhibition titled Lygia Pape – Magnetized Space that reunites some of Pape’s key artworks. Her earlier engravings, films, books and sculptures are part of this touring show that until the 19 February is on display at the Serpentine Gallery in London, was previously on show at the Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid and later this year is travelling to the Pinacoteca de São Paulo, Brazil.

Engraver, sculptor, filmmaker, and designer, Pape with an innovative and rich art practice that combines a range of media, is considered one of the most important Brazilian artists of the 20th century. She was a member of the Neoconcrete group that was a watershed among the Abstractionism tendency in Latin America. In Brazil, Abstractionism was mainly configured by its Concrete attributes, meaning a visual manifestation in which geometric elements were seen as a way of returning to what the artists believed to be the origins of the forms, seeking to transcend appearances, landscapes or figures. This pursuit for a universal visual language that impregnates Concrete art, in which the image is detached of symbolism, became a very strong influence for artists who, like Pape, wanted to rescue art from the “sclerosis condition”1 that was predominant in Brazilian art in that period. Nevertheless, within the Concrete ideology that nourished the art practice of the 1950s’ generation of Brazilian artists there were two principal moments: the initial moment that started in 1952 with the Manifesto Ruptura, in which the artists adopted a rigid position in relation to art, based upon perceptive theories and accepting reason as the supreme authority in determining the art practice; and later a second moment marked by a disagreement between the artists that were under the label Concrete Art. This second moment became formalised with the publication of the Manifesto Neoconcrete in 1959. The motif for the fissure between the artists was that the group that came to be known as the Neoconcrete group opted for a wide artistic path, with much more emphasis on sensorial elements and the artist’s gesture than following theoretical rules. Pape was among these people who stood for a more open understanding of art and alongside other members of the group such as Hélio Oiticica (1937–80) and Lygia Clark (1920–88) she later inaugurated what would be called “participative art”, in which the sensorial experience with the public is above any other rational output.

In Lygia Pape – Magnetized Space one can see this trajectory from the geometric forms on the plane to the incitement of open proposals that does not reside in the artistic object itself. The series of xylographs called Tecelares (1956–58) reveals the careful method of working that she used to establish the structure, volume and texture of black and white calculated shapes. The woodcut is undeniably a ruthless medium in which any oversight while engraving the surface is hard to fix and often leads the artist to start again from scratch. It can be imagined that it is even tougher for an artist who was in a process of synthetic reduction of expressive components. Creating Tecelares – that in Portuguese is the plural of “Tecelar” which means weaving, bringing the sense of a primitive procedure – from woodblocks clearly demonstrated mathematical rationality merging with organic life. During the peak of her Concrete Art production, Pape was indeed presenting what would be the core of her oeuvre after the Neoconcretism phase had passed. Whenever asked about her choice to keep working in such a medium, Pape used to explain that the woodblock gave her a different perspective in relation to the plane, she was obliged to work in a horizontal position, differently than when painting. Regarding the other impositions of the wood engravings, she made the following comment:

"I now had a black surface, of inked wood, full of small white incisions (the pores of the wood) and my knife bared the white space: firstly threads and surfaces that grew slowly, against the very system of xylography, where the white was discreet and almost always indicated the limit or profile of the image or figure. What interested me was to open bigger and bigger spaces (the white) to reach the ultimate limit of expression through a minimum of elements. An almost entirely white surface (the very negation of Xylo) and black threads vibrating due to the quality itself of the wood pores. (...) In fact, I was solving problems that went beyond the limitations of the engraving’s size. I think these engravings (Tecelares) have a monumentality, as if they were too big. They admit major expansions."2

Indeed, the lines of Tecelares went beyond their original scale in a transition to the sculptural installation Ttéia (first version dated 1977). The impressive gold and transparent filaments tied in a symmetrical manner from the floor to the ceiling are the heart of the exhibition. The artwork that was displayed at the 53rd Venice Biennale in 2009 captures the viewer in a delightful movement of light and poetic abstraction. Walking around the piece, at every step the spatial drawing changes. Ttéia’s bright and reflective monumental web is set up in a single gallery room, dedicated exclusively to it. Another highlight of the show is the artwork Livro do Tempo (Book of Time 1961-1963) that just like Ttéia gains a different structure every time that it is exhibited. It is constituted by 365 coloured 15 X 15 cm square wood surfaces. Again, the geometrical structure prevails designing yellow, blue, black and red types of icons that do not repeat themselves. Although they are a large set of small paintings on wood, it is titled ‘book’ as the intention of Pape was to create a calendar or better said a diary comprising all the days of the year.

Creating a work of art in the format of a book was an idea that had inspired Pape for many years. In the show is also possible to see the Livro de Arquitetura (Book of Architecture 1959-1960) that is an arrangement of 12 cut and painted sheets of paper. Each of them corresponds to a specific architectural style such as Palaeolithic or Gothic. Once more, the artist wanted to achieve the maximum with the minimum elements. In this case, she tried to playfully comprise the complete conception of construction using cutting, folding and gluing techniques. The other book that appears in the show is Livro da Criação (Book of Creation 1959-60) that is a variety of colourful inserts of papers which can be handled and are able to tell the creation of the universe according to the participant who interacts with or ‘reads’ the book. This book can be seen in a video in the exhibition, however the lack of information regarding what it is about does not allow the audience to identify the artistic project behind the scenes that were screened. In fact, the absence of contextualization is the weakest point of the show.

This deficiency can be realized in other artworks exposed in the show and is prejudicial to the comprehension of Lygia Papes’s fascinating artistic achievements. There are four other videos that suffer from the same omission consequently confusing the public that is not familiar with the artist. At no moment is it very clear which videos are related to her work as a filmmaker, or to the documentation of one of her performances, and if it is a performance, the provision of more details would shed light on what the audience is viewing. In addition to that, the organizers could have been more careful with the quality of the moving-pictures material that was presented. It would be considered acceptable to maintain a certain vintage aspect to them, as they are genuinely old films. However, the videos were in a poorly-preserved condition which could be restored without much cost. The objection to watching washed out and mouldy images is understandable. Another example to illustrate the absence of contextualization is the set of black and white photos that named the exhibition Magnetized Space, they are hung without any record of what they represent and it is more puzzling to see on the tags that they were not even photographs taken by the artist. A more respectful presentation of such an important artist would be appreciated.

For this reason it can be said that Lygia Pape-Magnetized Space is actually a fair gathering of the artist’s work but does not offer the whole dimension of the artist’s production. It is an error to call the show a “major retrospective” as part of the British media has been saying. It cannot even be called a retrospective as a revolutionary part of her work, the relational and participatory aesthetic discoveries which are ultimately the crowing result of Pape’s artistic trajectory, is not well introduced to the audience. Nevertheless, it is better late than never, that Lygia Pape is being celebrated with a solo exhibition in Europe.

Footnotes

1. The first stage of Brazilian Modernism in the 1920s brought a type of nationalism to art that was important but according to Pape not relevant in the mid 1940s or beginning of the 1950s, which is why she and other artists considered a ‘sclerosis’ the nationalism that was very figurative in this period. In: Cocchiarale, F., & Geiger, A. (first edition 1987) 2nd edition 2004). Abstracionismo geométrico e informal: A vanguarda brasileira nos anos cinquenta. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Funarte.

2. Extract from the interview with Lygia Pape published in Cocchiarale, F., & Geiger, A. (first edition 1987) 2nd edition 2004). Abstracionismo geométrico e informal: A vanguarda brasileira nos anos cinquenta. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Funarte.pp.152 e 163.