Irma Stern. A Modern Artist between Berlin and Cape Town, exhibition view, Brücke-Museum, Photo: Nick Ash.

Brücke-Museum, Berlin

13 July – 2 November 2025

by SABINE SCHERECK

There are not many women in the public eye within the sphere surrounding the German expressionist artists’ group Brücke, let alone women who were successful expressionists in their own right. Yet, there was Irma Stern. She is a major figure in art history in Africa, but in Europe, where the foundations of her career lie, the memory of her has been all but wiped out. Her strong affiliations to Brücke artist Max Pechstein prompted the Brücke-Museum to honour her with the exhibition: Irma Stern. A Modern Artist between Berlin and Cape Town. Her first solo show in Berlin since 1919, it presents 42 of her works, many of them shown in Berlin for the first time.

Stern was born in 1894 to German Jewish parents in what later became the province of Transvaal in South Africa. After her father was imprisoned by the British for his pro-Boer leanings during the second Boer war of 1899-1902, her mother returned home to Germany by sea with Irma and Irma’s younger brother. Irma went to school in Berlin until 1909, when the family resumed their lives in South Africa. Keen to forge a career in the arts, in 1913, aged 19, Irma returned to Germany to attend art classes in Weimar for a year before continuing her training in Berlin, where she lived until 1920. It was her encounter with Pechstein in 1917 that shaped her identity as an artist. He became her mentor and advanced her career by introducing her to Berlin’s art world. She exhibited as part of the influential avant-garde Novembergruppe and at Fritz Gurlitt’s renowned gallery. After this early success, she ventured back to Africa in 1920, only to find that there was little understanding of her art. Yet she persevered and is now seen as the woman who brought modernism to Africa.

Irma Stern. A Modern Artist between Berlin and Cape Town, exhibition view, Brücke-Museum, Photo: Nick Ash.

Being an inhabitant of two worlds – in fact more than that – her position within them is complex and marked by contradictions. The fact that she was an emancipated, self-determined woman, who travelled across Africa and Europe to capture their people and natural beauty in a modernist way, adds further facets to her remarkable persona. In Africa, she had the privileges of a white person but faced antisemitism. On a professional level, she was highly regarded because of her training in Europe. In Europe, she was seen as an expert on Africa and her portrayal of the continent was regarded as “authentic’authentic”, although she tended to serve up the picture picture-book view Europeans had of Africa. This means her African background did determine her motifs as there was a high demand for this in Europe.

This becomes directly evident within the Brücke group, for whom Africa also held a fascination. The group emerged in about 1900 when Germany was a colonial power and Africa would have been a frequent topic in the newspapers. In Dresden’s ethnological museum, the Brücke artists encountered African art in the form of masks and woodcuts, which left a mark on their own artistic style. It resonated with their pursuit of an art that was authentic, pure and not compromised by any bourgeois norms, which made African primal art very appealing. In this light, it made Stern not only an exotic artist but a very attractive one.

Irma Stern. A Modern Artist between Berlin and Cape Town, exhibition view, Brücke-Museum, Photo: Nick Ash.

Choosing South Africa as her base from 1920 onwards, she kept up a connection with Europe by commuting between the two continents to take part in exhibitions in major European cities, each time embarking on a six-week journey by sea. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, putting the lives of Jews at risk, returning to Germany was out of the question, and Stern focused instead on exploring Africa. She developed a deep love for the continent, where she remained until her death in Cape Town in 1966.

In the exhibition, the first painting of hers that you encounter following her introductory biography is Stonebreaker (1920), showing an African man against a green landscape with a hammer in his hand and a few stones in front of him. His eyes are closed and he looks slightly bored rather than exhausted from his work. The colour palette consists of subdued earthy green and brown tones. Typically for expressionism, the lines are angular. Altogether it is a calming image, non-judgmental and observing of nature. It was produced during a turning point in Stern’s life. She had just returned from Europe where she had established herself as an artist. But Europe was also a difficult place: the first world war had just ended and Berlin was scarred by a revolution. Turbulence in the city would last until the mid-20s, hence her decision to return to a warmer, sunnier and calmer place was a wise one. A watercolour from her journal, which is not further commented on in the exhibition, reflects the emotions connected to this move as she had added the lines: “And fled from burning Europe to the land of strong colours.”

Irma Stern, The Eternal Child, 1916. Oil on canvas. Rupert Art

Foundation, Rupert Museum, Stellenbosch. © Irma Stern Trust / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025. Exhibition view, Irma Stern. A Modern Artist between Berlin and Cape Town, Brücke-Museum, Photo: Nick Ash.

The exhibition briefly traces her beginnings, when she is still influenced by her teachers, who favour a more traditional style. The Eternal Child (1916), depicting a girl in a red dress, whose malnourished look shows her to have been marked by war, bears the first signs of expressionism and led to a break from her school. Pechstein recognised its merits and supported her from then on. In an adjoining section, the curators, Lisa Hörstmann and Lisa Marei Schmidt, have cleverly placed her works featuring African motifs alongside those by members of the Brücke group, which draw on exotic themes. Particularly striking is her watercolour Bathing Women (1922), which very much conveys an African sensitivity with its delicate lines and sandy colours. It is placed next to Otto Mueller’s drawing Two Seated Girls in Front of Lying Figure (1911). Stern’s image is also reminiscent of Erich Heckel’s drawing At the Pond (1910) in its style and motif, but Heckel’s picture is not displayed here and bears no links to Africa. Equally fascinating is seeing Pechstein’s Outrigger Boat (1914) next to Stern’s sketch from her 1920 portfolio Dumela Morena: Bilder aus Africa von Irma Stern (which translates from Tswana and German as Hello Sir: Pictures Out of Africa by Irma Stern). In rough lines, it shows two naked African men eating watermelons. It adopts a colonial attitude in its depiction of the Africans, which is unusual for Stern as most of her works portray them with great dignity, something that caused a stir in the conservative white ruling class in South Africa.

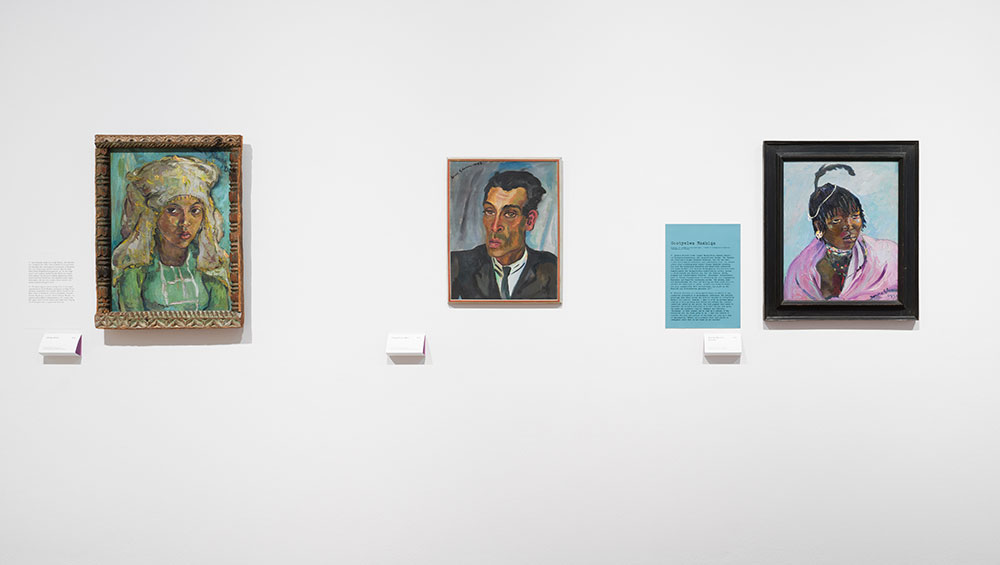

Irma Stern. A Modern Artist between Berlin and Cape Town, exhibition view, Brücke-Museum, Photo: Nick Ash.

A great selection of portraits she made of Africans in later years fills a long wall. They show men and women from different regions. Her emphasis is mostly on “types”, titling the images simply Congolese or The Golden Shawl, for example, yet she shows a genuine interest in the diverse African culture. Among her works are two images called Watussi Queen (1942 and 1943). The queen’s royal status is evident from her headdress and clothes, and she was later identified as Rosalie Gicanda of Rwanda, who married the king, Mutara III Rudahigwa, in 1942. It can therefore be assumed that Stern was commissioned to portray the new Queen.

The wall opposite presents landscapes often painted in lush greens. It also comprises a dialogue between her work and those by the Brücke group. Here, her painting Umgababa (1922) shows dark heavy clouds looming over green hills and a wide river in the foreground. Poignantly, railway tracks cut through the image and cross the water, hinting at the industrialisation to come. With its strong green and blue hues and tense atmosphere, it echoes Heckel’s ink and watercolour image Stormy Landscape (1913), which hangs next to it.

A notable insight into Stern’s life is given by the portraits of middle-class Jewish women, who also lived in South Africa and supported her. This led to acceptance and recognition after her expressionist style and way of portraying Africans were initially rejected. Among the series is Portrait of Rebecca Hourwich Reyher (c1920), an American writer, lecturer and suffragist who travelled frequently to Africa and had a great interest in its culture. These portraits were often commissions and reflect a more conventional rather than expressionist style.

Left: Irma Stern, Woman Sewing Kaross, 1929, oil on canvas. Right: Irma Stern, Maid in Uniform, 1955, oil on canvas. Exhibition view, Irma Stern. A Modern Artist between Berlin and Cape Town, Brücke-Museum, Photo: Nick Ash.

The final section shows African women in a different setting: as maids in white aprons in white men’s homes. One is Maid in Uniform (1955), showing a woman sitting with crossed arms and a rather sulky look. The other is Woman Sewing Kaross (1929), which has a more layered meaning: although a servant, she can carve out time to devote to her own culture when sewing a Kaross, a traditional southern African garment. The portrait shows that black people had some autonomy within their position as servants.

Athi-Ptra Ruga, Proposed Monument for Gladys, artistic intervention, vinyl, 2025. © Athi-Patra Ruga 2025. Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

It is illuminating to see the images by Stern, an artist influenced by the expressionism of the Brücke group, placed in the context of their work. This embraces her artistically formative years in Europe. However, as a wanderer between Europe and Africa, she also left a strong impression on art in Africa. The exhibition illustrates this, too, by including African artists who have taken inspiration from her output. One is the South African artist Athi-Patra Ruga (b1984), whose vinyl work – looking like stained glass – is prominently placed at the entrance. It shows the South African artist Gladys Nomfanekiso Mgudlandlu, a contemporary of Stern. Mgudlandlu is pictured with paintbrushes taking in the view of an African village below her. While connecting the two art worlds is a fine move by the curators to open up different perspectives, they added another layer by having African art experts commenting on some of Stern’s work. Although it is an honourable ambition to navigate the sensitivities emerging from white artists portraying black culture – particularly a century ago when racism, colonialism and white superiority dominated the view of the world – it stretches the visitor’s capacity to engage with the subject matter because there is already a lot to take in with regards to the complex context in which Stern produced her work. Nevertheless, this does not diminish the achievement of the exhibition, which it to look beyond the immediate circle of the Brücke artists and bring into view significant figures at its fringes.

Irma Stern. A Modern Artist between Berlin and Cape Town, exhibition view, Brücke-Museum, Photo: Nick Ash.