Hurvin Anderson in his studio. Photo: Sebastian Nevols. © Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery.

by ELIZABETH FULLERTON

Hurvin Anderson’s luscious paintings have hybridity at their heart. A perennial tug-of-war plays out between abstraction and figuration, beauty and menace and his British and Jamaican heritage. His latest series of canvases, produced under lockdown for his current solo show Anywhere but Nowhere, at the Arts Club of Chicago, centres on another conflict – that of the environment versus the manmade. Based on photographs from a 2017 trip to Jamaica, most of the new works in the show, on canvas, board and paper, serve as arenas for this battle between the local ecology and the island’s tourism industry, a battle in which nature seems to have the upper hand. Concrete chalets, palaces and walkways appear to be in the process of being swallowed up by rapacious vegetation that cascades and proliferates with abandon.

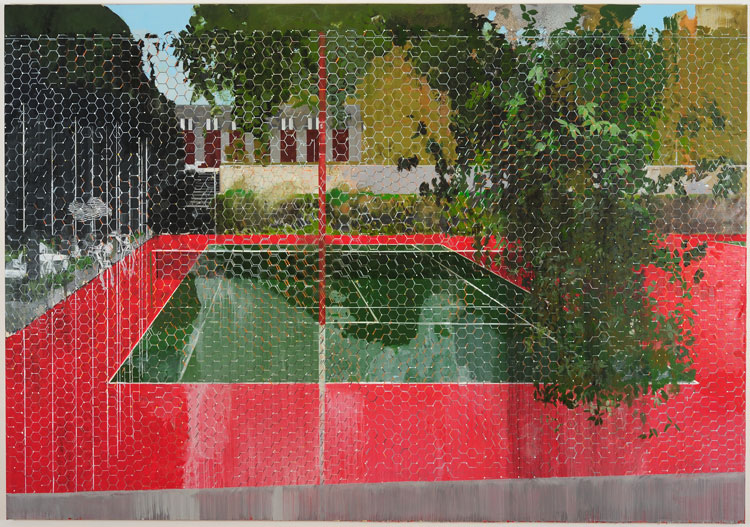

Hurvin Anderson. Country Club Series: Chicken Wire, 2008. Oil on canvas, 240 x 347 cm

(94 1/2 x 136 5/8 in). © Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo: Richard Ivey.

“It felt like the environment was inhospitable … and you had a sense of nature taking over, this idea of nature reclaiming the coastline,” Anderson said in a Zoom interview from his lockdown studio adjoining his home in Cambridge, UK. The artist, who was nominated for a Turner Prize in 2017, has a big year ahead. As well as this Chicago exhibition, he is included in the British Art Show, will be part of Tate Britain’s major exhibition Art from Britain and the Caribbean, and has a solo show at Thomas Dane Gallery at the end of the year. He also has a monograph coming out.

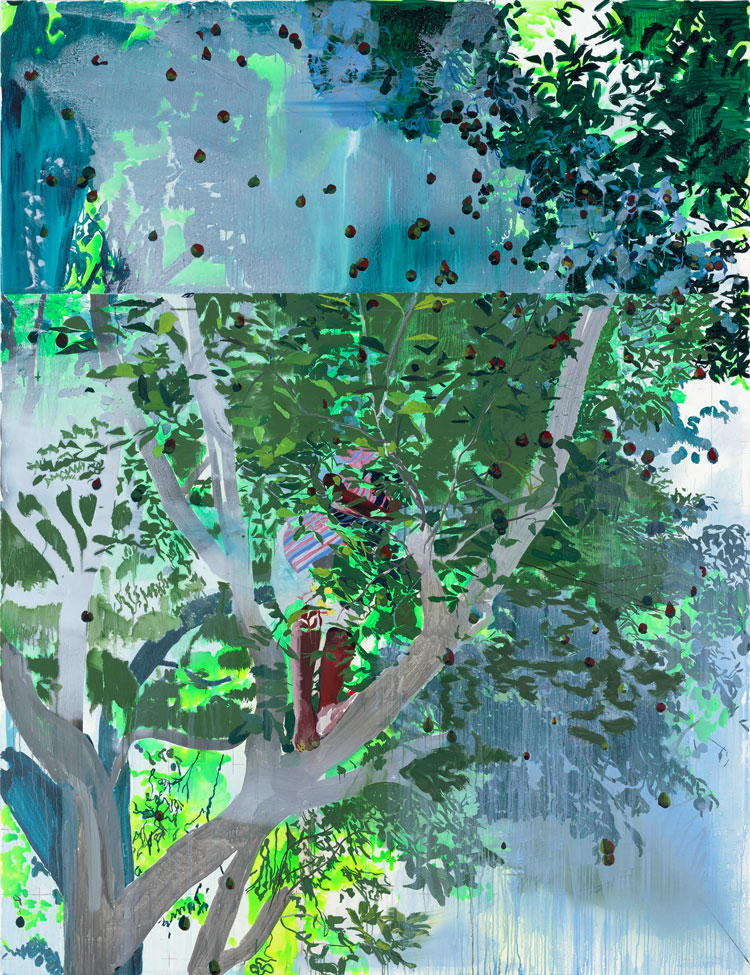

Hurvin Anderson. Rootstock, 2016. Acrylic, oil on canvas, 280 x 215 cm (110 1/4 x 84 5/8 in). © Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Michael Werner Gallery.

Anderson, whose parents were part of the Windrush generation of Caribbean migrants to Britain, often aims in his work to “‘create a new space” where contradictory elements coexist. With his 2016 painting Rootstock, for instance, he amalgamated a mango tree from Jamaica with a pear tree from Britain, layered with memories of his brother “scrumping for apples”as a child. His best-known works, the Barbershop series (2006-ongoing), similarly carved out a distinct space, capturing the fragmentary nature of diasporic identity, while fusing abstract and representational elements. Inspired by visits with his father to a barber who cut hair in his attic, the paintings conveyed the importance for the Afro-Caribbean community of these makeshift spaces, often in people’s homes, that serve as a space for meeting and swapping gossip – and a refuge from often hostile British society.

In addition to themes of memory and belonging, his new series of urban landscapes addresses a disconnectedness from the Jamaican idyll of his imagination, as hinted at by the exhibition’s title, Anywhere but Nowhere, a song by the late reggae singer KC White. “I felt like I was supposed to have an attachment to Jamaica,” he says, “and you got there and, yes, you understand the culture, but still there was a detachment. Somehow you couldn’t embed yourself in it.”

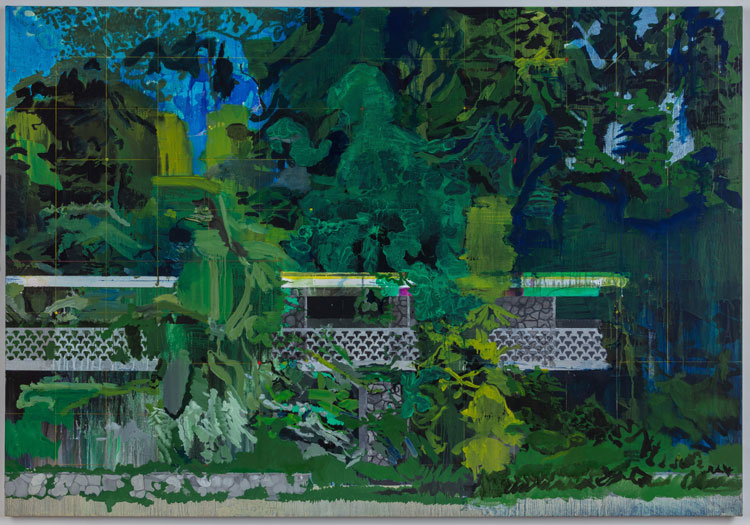

Hurvin Anderson. Limestone Wall, 2020. Acrylic, oil, coloured pencil on linen, 150 x 217 cm (59 1/8 x 85 3/8 in). © Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo: Richard Ivey.

Anderson was born in Birmingham, in 1965, the youngest of eight children and the only one who was not born in Jamaica. His ancestral home represents “a kind of loss” for him. “Many Jamaicans came here in the 50s and 60s and always referred to Jamaica as the ideal. They missed it, they felt unsettled here, so it became a utopia. Jamaica was always discussed as a place where we could be our real selves,” he says. “Of course, a lot of people haven’t ever gone back.”

This ambivalence is played out in his works. In Hawksbill Bay, for instance, a burst of electric blue vegetation appears to have a life of its own, spilling over concrete walls and burgeoning from the centre. (The blue is, in fact, the foliage of two palms melting together, Anderson says, but it appears as a single dominant force in the image.) Similarly, Jungle Garden is a teeming profusion of urban shrubbery obscuring a dull building complex behind, and in Limestone Wall, the beleaguered wall of the title seems to be under siege from the natural environment, with the foliage from the back invading the foreground. In these unsettling depictions of nature, the tropical plants are portrayed in gorgeous hues – fuchsia, indigo, marigold and a dizzying array of greens, teals and olives. Washes are juxtaposed with drips, smears, layers of colour and wispy fronds in these subtle works that inspire prolonged contemplation.

Hurvin Anderson. Jungle Garden, 2020. Acrylic and oil on linen, 181 x 150 cm (71 1/4 x 59 1/8 in). © Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo: Richard Ivey.

“I am looking at where things collide, how these things respond to each other. I like the contradictions and the friction that results. I have been thinking of things like overlapping worlds,” Anderson says.

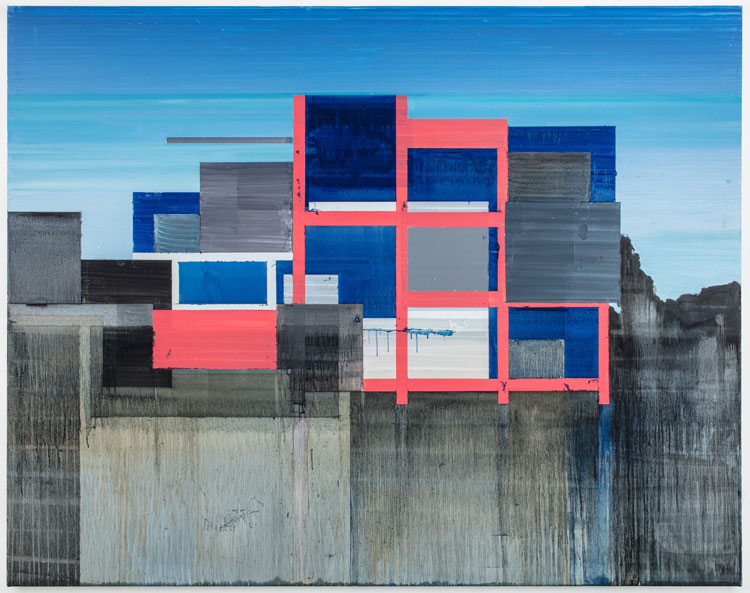

The inhospitable ambience is also present in the painting Higher Heights,which shows a futuristic-looking hotel that is all stacked blocks, but could equally be seen as a geometric arrangement of grey and blue cubes in a vivid pink framework. Anderson is fond of the directness of the single perspective, he says. “I think I picked it up on the way from looking at Claude and Poussin, almost looking on a stage and watching. So there is directness, but the sense of being apart from it too.”

Hurvin Anderson. Higher Heights, 2020. Acrylic, oil on linen, 150 x 190 cm (59 1/8 x 74 3/4 in).

© Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo: Richard Ivey.

Anderson’s more geometric compositions suggest affinities with modernist explorations of the grid, but he says that with Higher Heights, for example, he was looking at David Hockney’s blocky 1967 painting Savings and Loan Building. Francis Bacon is another inspiration. Anderson thinks of the grid lines he sometimes leaves in the works as creating “a psychological space within the painting”, not unlike Bacon’s cage-like framing devices.

In his childhood, Anderson’s brothers were formative influences; Rupert drew, and Claude made cartoons and introduced him to the camera. The 1989 Hayward Gallery touring exhibition The Other Story, which was curated by Rasheed Araeen and showcased the work of artists including Sonia Boyce, Frank Bowling and Keith Piper, also had an impact when he saw it in Wolverhampton. Anderson trained at the Wimbledon School of Art and the Royal College of Art. A turning point came in 2002 when he attended a residency in Trinidad, which provided him with rich material to explore Caribbean post-colonial life. Inspired by the security grilles he had seen everywhere, which are designed in attractive patterns but serve a protective function, he began breaking up the unity of his seductive compositions with ornate fences and screens. In a way, the confrontational nature he portrays in these latest paintings has a similar distancing quality.

Hurvin Anderson. Study for Jungle Garden 3, 2019. Ink on cartridge paper, 33.4 x 31.2 cm

(13 1/8 x 12 1/4 in). © Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo: Ben Westoby.

The artist works from photos, making sketches where he strips away elements to get at the “underbelly” of a subject. The Chicago show includes numerous studies in ink or paint on paper, which have a more fluid and abstract feel than the paintings. Working in a confined space during lockdown has forced Anderson to relax his usual strictures, which he says is reflected in the works. “I can see there’s some clumsiness going on in places, but even that I don’t mind because, before, I could be so controlling and actually now I was trying to bring new elements in and see what happened.”

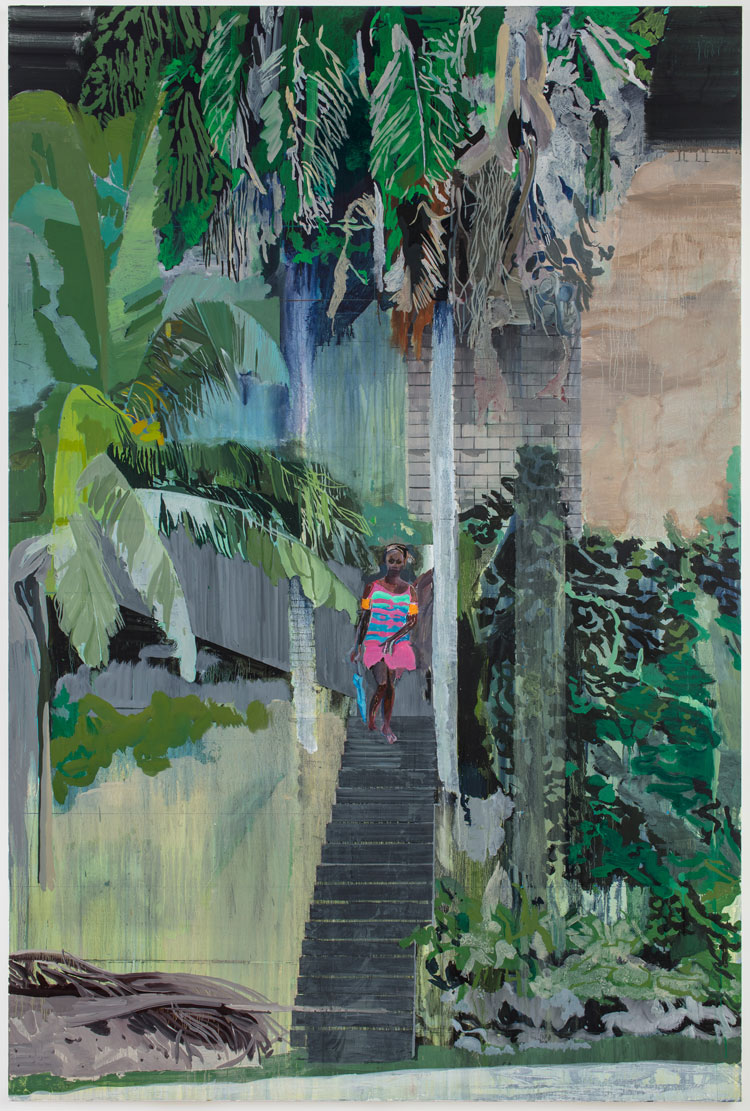

Hurvin Anderson. Grace Jones, 2020. Acrylic, oil on linen, 224 x 150 cm (88 1/4 x 59 1/8 in). © Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo: Richard Ivey.

Interestingly, out of 25 works in the show, only one, the painting titled Grace Jones, features a figure. Although stunted by towering palms, she cuts a vibrant presence in a bright-pink dress with a blue parasol. “In Jamaica, people very rarely wear dark colours,” says Anderson. “There’s always a brightness that projects them forward and it was irresistible to have this figure in this colour coming down those stairs.” It’s not the singer of the title, although Anderson felt there was some facial resemblance, but he confesses that titles are a struggle. He seems mistrustful of words in general, taking time to find the right ones and correcting himself when he speaks.

Figuration is another challenge – not in terms of the artist’s proficiency, but figures seem to slip out of his grasp, rarely materialising in the paintings, although a human presence is almost always implied. “Sometimes, I’d like the human form to appear more often in the work. For some reason, they never appear,” he said. “It happened again with Miss Jamaica. The idea was to have two figures immersed in the environment, but it didn’t happen.”

Hurvin Anderson. Miss Jamaica, 2021. Acrylic on paper, 238.7 x 191.8 cm (94 x 75 1/2 in). © Hurvin Anderson. © Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo: Ben Westoby.

Miss Jamaica is among several works relating to the Barbershop series that Anderson is presenting in Chicago, including the glorious pink-dominated Flat Top from 2008 and several, mostly greyscale, studies. Miss Jamaica comprises blocks of yellow and black on a pale-blue background above a rust countertop, the only clear representational elements being a green spider plant and a bottle, whereas some works in the series have included the chairs, hair products, scraps of hair on the floor and sometimes a figure or two. The Miss Jamaica of the title refers to a postcard on a shelf and seemed to contradict the sparseness of the painting, according to the artist.

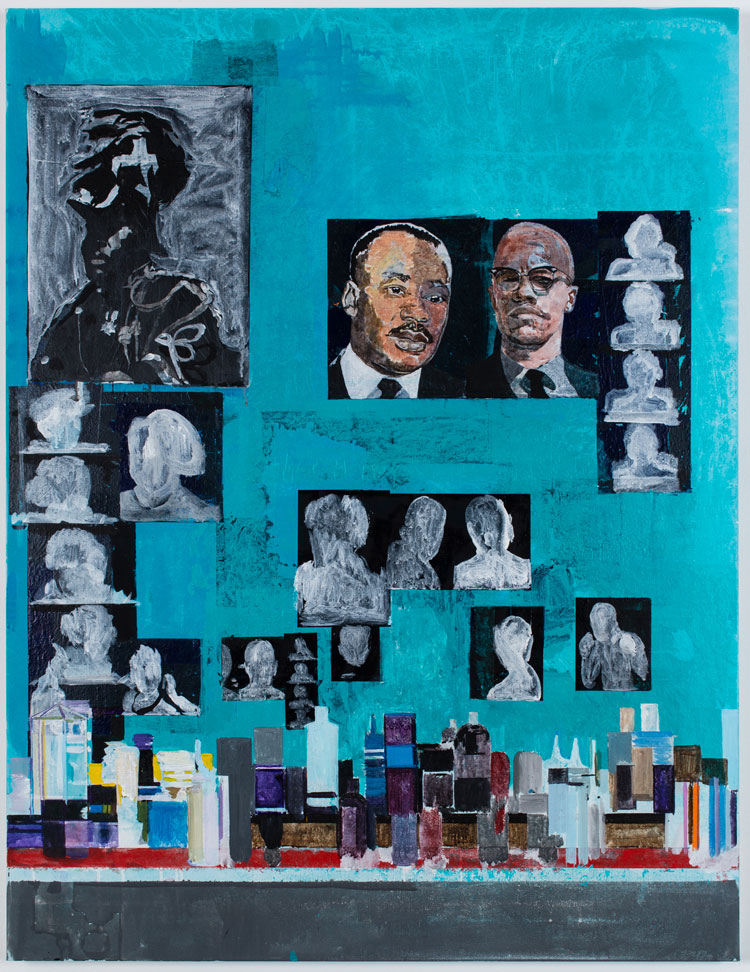

In 2016, Anderson made a rare foray into identity politics with his superb painting Is It OK to Be Black?, featuring posters of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King on the turquoise barbershop walls, alongside multiple silhouettes and bottles of hair product. The work featured in his particularly strong offering for the 2017 Turner Prize show.

Hurvin Anderson. Is It Ok To Be Black?, 2016. Oil on canvas, 135 x 100 cm (53 1/8 x 39 3/8 in). © Hurvin Anderson. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery and Michael Werner Gallery.

What prompted him to ask the question at that moment? “I was trying to make a painting about figures that were seen as influential to the black community in Britain. There was a sense that there was a side to take – either of Malcom X or Martin Luther King – and I wanted to bring the two of them together,” Anderson says. The context was significant, too. Michael Brown had been shot in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, sparking violent rioting; in 2016, the quarterback Colin Kaepernick had taken the knee during the US national anthem, in protest at police brutality; and, finally, in the UK, the reverberations of the police killing of Mark Duggan and subsequent rioting were still being felt. “The title came out of all the conversations around these events really and seemed relevant at the time,” the artist notes.

Anderson has tried to end the series, but keeps returning to it. “I would love to stop,” he says, laughing. “I don’t want it to become a cliche. You know, black culture in barbershops and so forth, I’m a little bit nervous of that, but I am aware that it seems to be this vessel where all these ideas can appear or explode.”

• Hurvin Anderson: Anywhere but Nowhere is at the Arts Club of Chicago until 7 August 2021.