Installation view, Hinterlands, Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, 2022. Photo: Rob Harris. © 2022 Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art.

Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead

22 October 2022 - 30 April 2023

by VERONICA SIMPSON

Hinterlands is a show that invites us to pay closer attention to the wild landscape, whether urban or rural, to the terrain around us in which nature finds space, holds sway – fights back even – over the dominance of human interventions. Hinterlands here is used in the literal sense of “the land away from the coast or the banks of a river”, as well as the more metaphorical sense, as in “what lies beyond the visible or known”, according to the show’s publicity.

It is perfectly timed for its winter slot, given our tendency to cocoon ourselves in our centrally heated homes and offices at this time of year, turning our backs on gardens, parks and wilderness. And the three curators (Emma Dean, Niomi Fairweather and Katharine Welsh) have conjured a kind of wilderness on the third floor of the Baltic, this former flour mill that looms over the River Tyne.

Jo Coupe. After the Rain, 2014-22. Installation view, Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

We are ushered into a dark and starkly spotlit plain for the opening works: Jo Coupe’s After the Rain (2014-2022). Here, an assortment of sound dishes, umbrellas, parasols and paint rollers stand like sentinels, while a looped stereo track broadcasts the crackle, buzz and birdsong of some wild place – a place newly cleansed and charged after a rain shower, presumably. The spindly legs, dish-like “heads” and pleasing shadow patterns of the objects create a strong feeling of suspense: are they transmitting the sounds or listening in on them? I like the way the bleed-through of a powerfully windy soundtrack from deeper inside the exhibition promises further elemental explorations, drawing us into this wonderfully immersive exhibition.

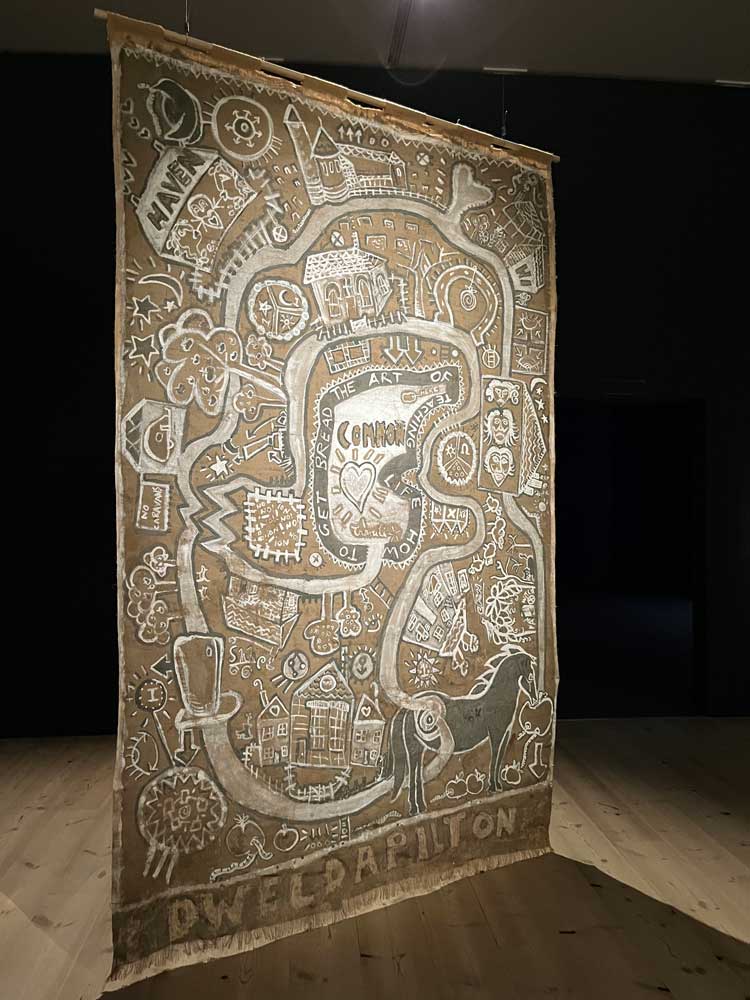

Emily Hesse. Banner for Appleton Common, 2022. Installation view, Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

There is a really nicely considered curation of materials and methodologies here, even in this first room – the stark silhouettes of these ready-made objects, transformed into active presences, followed by two works by Emily Hesse, who sadly died in November. Hesse’s labyrinthine, cave-painting-like textiles made from local clays and oil paints on hessian offer a soft tactility as well as summoning the enduring spirit of primitive and contemporary mark-making. Banner for Appleton Common (2022) is backlit to great effect. On the opposite wall, we have the fragility and fire-forged brittleness of glass, thanks to Anne Vibeke Mou, with two blown-glass works in cases, and then two framed glass slabs adorned with diamond-point engraving, depicting in extraordinary detail the complexity of organic matter. One, Untitled 2020, identifies its subject as a “tapestry of lichen found in remnants of ancient woodlands and plantation forests in Northumberland”. The other, In the Spoils of Flinty Fell (2022), is “lichen growing on a fell shaped by millennia of mining, engraved on mid-19th-century window glass from a house in Newcastle upon Tyne.”

The spirit of paying close attention to that which is under your nose is so vivid in all these works – and very specific to this locality. The show is a real celebration of the artistic ecosystem here in Newcastle, as well as the natural one. Though many of the artists are not from here, all are based here, and most with many years of deep observation of the local terrain under their belts.

-20.jpg)

Laura Harrington. Fieldworking, 2020. Installation view, Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead. Photo: Rob Harris. © 2022 Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art.

Laura Harrington is a case in point. The works shown in the second room are the fruit of eight years she has spent contemplating the “complex relations between humans and landscapes”, in particular the blanket bog and moorland of the North Pennines and Upper Teesdale. Fieldwork is a core part of her practice, and Fieldworking (2020) the name of the film whose windswept soundtrack we heard in the distance as we entered the first gallery. The scene playing as I arrive shows a bunch of hikers in high-visibility waterproofs, who appear to be taking the slowest of slow walks across a Northumbrian heath. They seem immobile initially – I wondered if it was a still image – and then I noticed their trousers and strands of hair moving in a stiff breeze, along with the grassy turf at their feet. I think this slightly cartoonish slowing of their progress is intended to make visible the usual fleeting momentariness of a walk against the ancientness of the landscape.

The film is 29 minutes long. I don’t say this about many video works, but it is worth sticking around for the whole thing. It is hypnotic and riveting in the thoughtful, serious way these hikers (who turn out to be friends, fellow artists, ecologists and film-makers) traipse, stand and dwell in this terrain. The chopping and layering of scenes visually meshes wonderfully with the shifting sound worlds, from the deafening crunch of slow-moving sports shoes that have been specially miked up for maximum immersion to a deep, wet, bubbling underground waterscape picked up by a microphone buried in the bog, and the way the film blacks out from time to time, switching from misty moor to what could be the fabric of a tent – the rattling of wind on canvas is certainly a dominant sound in the film.

-23.jpg)

Laura Harrington. Vegetation Blanket #4 (a wonderfully accidental anti-connection), 2022. Made in collaboration with Michele Allen, Anne Vibeke Mou, Dawn Felicia Knox, Sabina Sallis. Installation view, Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead. Photo: Rob Harris. © 2022 Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art.

Harrington also has four dense and darkly complex ink drawings on show (Hagg #1, 2, 3 and 4, all from 2014). Here she captures eroded landform remnants, or “spirit forces”, shaped by time and nature. There is also a collaborative offering: Vegetation Blanket #4 2022, a felted-wool sculpture, looking like the pelt of some exotic, rainbow-hued sheep or goat, something organically matted rather than created. This piece was formed in collaboration with other artists in the show, Michele Allen, Vibeke Mou, Dawn Felicia Knox and Sabina Sallis, while “having a conversation about landscapes, friendship, artistic practice and the places where things meet”.

-70.jpg)

Alexandra Hughes. Installation view, Hinterlands, Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, 2022. Photo: Rob Harris. © 2022 Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art.

In the next room along, Alexandra Hughes presents her photographic and sculptural collages, which she says are formed by a process of “wilding”, in which she removes herself from the need to represent objective reality. Her pieces for this show include a series of sliced and curved photo cut-outs, their colours given a stained-glass intensity on lightboxes, and fabric hangings. Perhaps thanks to her emphasis on disassociating the works from their setting, I find myself disassociating from the works, though I enjoy their richness, their somehow anatomical references - one is almost like slides from a biology lab - and the iridescent tape that trails, snail-like across the space between the standing frames, as if mapping a landscape of sorts on the gallery floor.

-78.jpg)

Dawn Felicia Knox with Anastasia Clarke. The Felling, 2022. Installation view, Hinterlands, Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, 2022. Photo: Rob Harris. © 2022 Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art.

The work beyond it is absolutely wedded to a specific landscape: The Felling (2012-22), by Dawn Felicia Knox, is a moving image installation of projections of nature (taken at Felling Colliery), filmed and photographed in various seasons. It feels all the more vividly present for the three dimensionality of its set-up - the way the images shimmer and sway across the stacked, propped and draped combination of screens. And its presence in the room is made larger and richer thanks to the soundscape made with Anastasia Clarke. The extraordinary noises we hear are apparently taken from “field recordings synthesised through sonified data of bracken and mugwort pulling heavy metals from the soil first into their roots then branches and into their leaves”. This is not some fanciful conjecture on the part of the artists but fact: Felling Colliery is the subject of a 10-year (at least) investigation by Knox, who was drawn to work with plant fossils excavated from the site (which, at the time of their discovery were the first of their kind to have been seen by humans, and helped geologists to identify the age of our planet), and most of the plants filmed for this work are those surviving against all odds, on now defunct mines, twisting out of the coal spoil heaps and in their own, plant behaviours, cleansing the land polluted by humans.

Mani Kambo. Installation view, Hinterlands, Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, 2022. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

After this comes the calm, graphic quality of Mani Kambo’s symbols and patterns on banners, white fabric paint on black cotton. There is such a sense of zooming in and out with this show – both with the specific items of nature and locations, but also time. Kambo’s fabrics zoom out a little further than most, spiralling us into the structures of plant roots, and then out into space and the cosmos, the sun and the stars.

Baltic’s head of curatorial and public practice, Irene Aristizábal, tells me the show came together over the course of a year, the first year of the pandemic and the lengthy lockdowns. “We decided on this exhibition two years ago (2020) as a way to think about the local landscape and geology, also from the perspective of property and how we connect with landscape and our relationship to the natural world, and also to think about time, from the perspective of our custodianship of the land.”

Michele Allen, The Weight of Ants in the World, 2018-ongoing (detail). Installation view, Hinterlands, Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, 2022. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

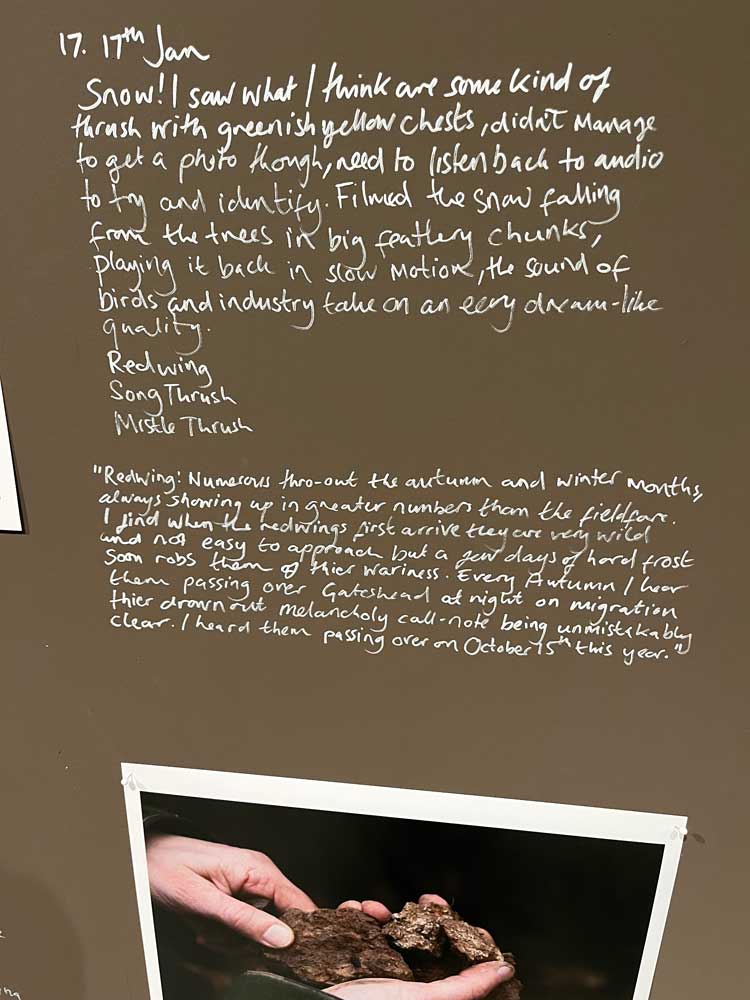

It genuinely conveys that sense of the expanded bandwidths many of us experienced, our connection with time, work and our surroundings shifting dramatically with each phase of that stark and unfamiliar (to most of us) global event. One of the curatorial masterstrokes is the generosity of space each artist and their preoccupations are given. We are able to see how the relationships between artist and place and theme have evolved, and nowhere more so than with the installation by Michele Allen, who has come to know intimately a strip of ancient woodland in the heart of a Gateshead industrial estate. The Weight of Ants in the World (2018-ongoing) takes the form of video, photography, text and collected specimens. I particularly liked the way her photographs are given so much space across one wall, each one accompanied by dense diary-entries written on to the dark wall in pale handwriting. It presents very much like a scrapbook, giving us a sense of her evolving relationship with this site over time, her growing appreciation of its qualities, her interactions and engagements with wider communities and, eventually, the certificate for a tree preservation order from the local council, guaranteeing protection for one particular tree of interest. For all that work of this durational intensity and quality has its own merits and fascinations, this shows that it also has positive impacts on the site: thanks to the attention Allen and assorted ecologists have paid to it, not only is that tree protected but the woodland is now designated a local wildlife site.

-26.jpg)

Sabina Sallis. Apparatus for Resurgence in Trophllaxis: Greetings from the Mother of Herbs, 2019 – ongoing. Installation view, Hinterlands, Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, 2022. Photo: Rob Harris. © 2022 Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art.

Sallis concludes the show with a fragrant and enticing structure made of coppiced hazel, copper, straw, herbs, thread, honeycomb, mushrooms and assorted materials - a woven temple to nature and healing that she calls Apparatus for Resurgence in Trophallaxis: Greetings from the Mother of Herbs (2019-ongoing). This, as with all the works in the show, invites hours of leisurely examination, and will hopefully inspire multiple, and repeated visits – something which Aristizábal is fairly confident will happen over the show’s six-month run. She tells me the excellent Baltic Crew (so much more than gallery assistants) have noticed how much visitors, especially locals, are enjoying the show. She says: “They are asking lots of questions. And they have pride in seeing artists from their own context being shown in a place that’s normally showing artists from elsewhere.” That’s another fine way of ensuring the show instils among its viewers an appreciation of the talents and treasures under their noses.

-58.jpg)

Installation view, Hinterlands, Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, 2022. Photo: Rob Harris. © 2022 Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art.