Charlie Stiven. Photo © The Artist.

by JANET McKENZIE

Charlie Stiven is an Edinburgh-based artist, who has exhibited widely throughout Europe and the US. He has held solo exhibitions in Edinburgh, London, New York, Bern, Wrocław and Belgrade, and has been included in numerous group shows in Berlin, Boston, St Louis, Basel, Madrid, Zurich and Seoul. As a lecturer at Edinburgh College of Art, where he is programme director of painting and where he also trained, he has initiated projects with students of the Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Stuttgart, and the Universität der Künste, Berlin.

His exhibition Kiosk, which was at Summerhall, Edinburgh, from July last year until February this year, presented small handmade, 3D models that replicate European vernacular architecture to address experience on individual and societal levels, at a critical and unprecedented time in history. Life in the UK has been damaged as a consequence of political and economic opportunism and neglect and not least by the breakdown of civility and trust in political life. The modest entities of kiosks allude to personal isolation, victims of political policy, enactments of existential drama, yet they are neither nostalgic nor sensationalised. Truth to their context is established through hyper-concentrated construction, and the incorporation of detritus and found materials.

Charlie Stiven: Kiosk, installation view, Summmerhall, Edinburgh, July 2023 – February 2024. Photo © The Artist.

The works in Kiosk resonate with the fragility of individual lives and small communities in the face of global systems of production, communications and consumption. Resembling architectural models, Stiven’s sculptures are vestiges of marginalised culture. Based on extensive travel, a detailed research process and photographic documentation, the series is drawn from a range of subjects: a watchtower in Serbia, buildings in Gdańsk, a refreshment kiosk in Athens, a pharmacy in Madrid, an art nouveau railway station in Lviv, Ukraine, a seaside kiosk in Blackpool.

Stiven’s work is replete with references to metaphor and fiction: from Bruegel’s Tower of Babel to Fritz Lang’s pioneering 1927 film Metropolis and Piranesi’s (1720-78) series of etchings, Imaginary Prisons. Stiven began the Kiosk series nine years ago, as the UK lurched towards Brexit, an intense emotional period against a backdrop of deception. Stiven’s original work is at once political and psychological, speaking to the ramifications of financial meltdown, political expediency and anticipatory loss.

I met the artist at Summerhall, as he was preparing an installation for the Edinburgh Festival.

Janet McKenzie: Can you explain what you are exhibiting in Edinburgh this summer?

Charlie Stiven: I’m installing one piece of work shown in the Kiosk exhibition for permanent display at Summerhall. This is pleasing not only as a reminder of that show but importantly as a signifier of my huge respect for Summerhall as a venue and institution. It’s a place both rooted in the community and one that reaches out and speaks internationally, with a philosophy that is deeply humanistic and inclusive. To be tangibly connected through the siting of the work there feels really good and seems in many ways a very natural fit.

The piece in question, End of the Pier Show, is a plinth-based 3D work modelled on an archetypal British seaside kiosk, now abandoned and dysfunctional, the pier on which it sits cut off and isolated, a metaphor for Brexit and its resultant effects.

Charlie Stiven. End of the Pier Show, 2019 (remodelled 2023). Wood, acrylic, mixed media, 36 x 36 x 46 cm. Photo © The Artist.

I remember as a child visiting Blackpool and being seduced by the arcades, promenade and tower. In actuality, of course, Blackpool, like many other British seaside towns, is blighted by neglect and resultant societal problems, which proved fertile ground for populist Brexiters. In a wider sense, the work reflects a Britain that never was, a hollow romantic vision shaped by introspection and “bread and circuses” cynicism.

Piranesi has been one influence – another would be the German author WG Sebald, who writes so eloquently about aspects of architectural histories, time, perception and memory. The work is hopefully imbued with a similar fragile melancholia.

JMcK: The understatement in your work conveys marginalisation and loss. Can you describe the thought processes involved in making the Kiosk works?

CS: Standing alone from more permanent architecture, street kiosks to me seem inherently exposed and transient, susceptible to the flux and flow of time and human behaviour – in a sense analogous with ourselves as small, fragile entities within a larger context. Street kiosks really came to the fore during the time of rapid urban development in the 19th century. Indeed, the image of the Victorian match girl standing outside theatres and pubs exemplifies the connection between small-scale trade and aspects of the human experience – the match girl with her tray being in a sense like an unfixed and highly vulnerable kiosk.

The presence of street kiosks is more commonplace in mainland Europe than the UK and my initial responses were triggered by consideration of pan-European circumstance (such as the financial meltdown in Greece and to a lesser extent Spain in the 2010s) rather than purely British phenomena. I’ve long been interested in the emotional impact of architecture, space and structure, and see these kiosks as being akin to small capsules showing cause and effect, containers of history resonant with allusions to the human condition.

Charlie Stiven. Farmacia, 2016. Wood, acrylic, mixed media, 45 x 45 x 34 cm. Photo © The Artist.

JMcK: You have developed an original methodology with a keen interest in model-making and architectural models, of deconstruction and reconfiguration? Can you explain the processes?

CS: In one sense I suppose model-making is traditionally, and rather superficially, associated with small-scale depictions of an “ideal’, be it an amateur train set or an architect’s propositional maquette, a representation of something perfect. While recognising and seeking to utilise the lyrical qualities inherent in intense, small-scale construction, my work is the opposite.

By and large, my models are not replicas of existing buildings, but rather structural composites, amalgams and inventions drawn from numerous sources – visiting and cataloguing existing structures and then deconstructing, mixing and evolving new arrangements with the aim of creating a heightened metaphorical tension. I see this process as being rather like abstract painting, considering the balance/imbalance of form, line, proportion and angle in order to create something that has a certain harmony and completeness, but which also alludes to something bigger, something “other”.

In life in general, I have a keen interest in micro equals macro, small things that result in or allude to bigger things, and this knits into my focus on model-making – by really paying attention to the small things, one begins to recognise and understand the bigger picture.

My working pattern could be split into: considering architectural structure; researching aspects of history and contemporary socio, economic, political circumstance; evolving creative strategies from this; making the work. However, this would be simplistic: the attention to process and materiality when making the work is not only guided by previous research, it is very much part of it. The making process, discovering ways to manipulate the tools and materials I use, breathes life and depth into my conceptual concerns – idea and process thus become one, a synergy that I feel is vital to the success of any artform.

Just as shape and structure can contain a particular poetry so, too, can touch and nuance – the manipulation of colour, surface and tone, and the resultant impact of this, is very much an intellectual and emotional process as well as a visual one.

Charlie Stiven. GRAB N’ GO, 2020 (remodelled 2023). Wood, acrylic, mixed media, 60 x 80 x 33 cm. Photo © The Artist.

JMcK: The use of architecture that does not imply power is key to your political or social message. What is it about modest, unremarkable buildings that you are drawn to?

CS: I find such places more open and resonant than more consciously conceived structures, many of which are designed to transmit a predetermined atmospheric or subliminal message. These commonplace buildings represent us and aspects of our everyday lives, functional, quiet, small and transient. They seem to me to be able to soak up and convey traces of humanity and past/current presence more effectively, their often-unkempt appearance alluding to personal and societal histories and circumstance in a more honest way than larger edifices, which often seek to either hide, or show a very particular version of truth. They are also to be found everywhere, their ubiquitous nature mirroring the widespread nature of the metaphorical points I am seeking to make.

Many of my works have what might be described as a distressed appearance, of being at or near a stage of abandonment, and I would like to make an important point about this. I am very aware of the phenomena of “ruin porn”, of giving dysfunctional architecture a kind of voyeuristic sexiness in order to claim a connection with it. This is exemplified by the rash of expensive coffee-table books relating to, say, the inner-city collapse of Detroit, or compilations on Soviet-era housing blocks and so forth – beautifully printed perhaps, but without real humanity or meaning.

The depth of my connection to subject matter and concept comes through contextual knowledge attained and via my responses to this, articulated, as already mentioned, by an intense engagement with the process of making. My way of working in the studio is technically very demanding and takes time. This necessitates absolute focus, concentration and awareness, a mindset that moves between acute thinking about what one is doing, and the reasons why. The depth of this studio engagement absolutely mirrors the level of my concerns re subject matter and conceptual purpose, the intensity of the finalised work intended to signify levels of humanitarian care and concern rather than being merely demonstrations of technical dexterity.

JMcK: I am very excited to see your detailed perceptual drawings from the 1980s to the 2000s and to discover that drawing was your primary practice for a long time. How does such a forensic drawing practice lead to your recent practice?

CS: A fundamental commonality between the earlier drawings and the models I now make is the level of connection with the tools used for each. The drawings utilised charcoal sticks, Conté pencils and putty rubbers, and the models required small hand tools such as files and saws. It is absolutely not overstating the case to say my relationship with these things can be akin to love, a true and total emotional, tactile and intellectual bond between chosen means and my own sensibilities. These tools are held in my fingertips, which are connected to my nervous system, which is connected to my brain, which is connected to my heart – as such, they are an extension of myself.

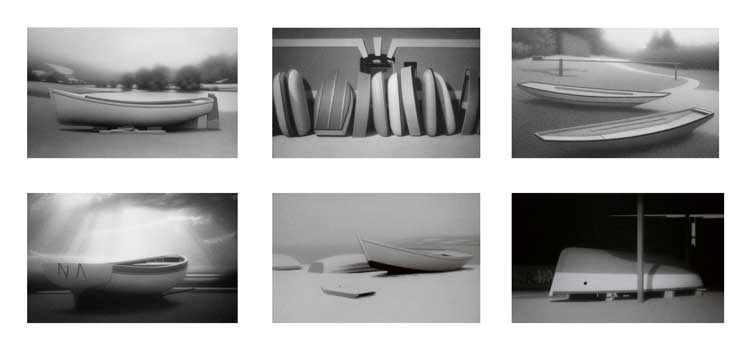

Charlie Stiven. Drawings from Dry Land series, 2000s. Charcoal, Conte pencil on Arches paper, 50 x 70 cm each. Photo © The Artist.

The drawings were also concerned with metaphor and aspects of the human condition triggered by my societal observations and, like the models, contained highly crafted and subtle variations in tone, surface and form. Again, like the 3D work they looked realistic, but were largely contrived and invented in terms of composition and content in order to transmit a particular response. They were hard won and slowly realised – I believe very much that one does not need to be loud to be expressive and that quiet, deep contemplation and response can be hugely potent and effective.

The drawings were successful in that I had gallery representation in New York and Switzerland for a number of years and they sold well, but that became a bit of a treadmill and conceptually I reached a point where I didn’t know how to develop them further. At about the same time, model-making became an increasing itch that I needed to scratch, so I did. When I was young, I was totally obsessed with plasticine and making small 3D scenarios – a friend recently relayed a piece of writing by Carl Jung in which he stated that one only finds happiness as an adult by rediscovering that which brought solace as a child. That does seem a bit introspective, but if allied to ways of responding to the world – maybe!

.jpg)

Charlie Stiven. End of the Pier Show, 2019. Model as photographic prop. Photo © The Artist.

JMcK: You sometimes also use photography as a means to produce finalised work. How does drawing, photography, painting and making with a wide range of materials come together in your present practice?

CS: I have to say I don’t yet have the same connection to photography as with other stated mediums, but it is something I’m continuing to explore. The nature of the models lends itself to be considered as elements of a stage set, and I think there is interesting territory to be explored via photography in relation to heightened levels of visual and psychological perception. Taking carefully constructed photographs of the models, utilising lighting and atmospherics in a similar way that one might do when constructing a drawing or painting, opens up the possibility of producing what in effect are trompe l’oeil images, a kind of pretend reality. I have done this, but what I’m really interested in playing with through photography in future is evoking more subtly a kind of slow-burn realisation, of discovering elements and strategies whereby the fact that what one is looking at is a fabrication, and not reality, becomes very slowly apparent, so that one is rewarded by truly looking and encouraged to question what one sees. To date, I’ve been in a sense too successful in fooling the eye, where people very often think that the model is made from the photograph rather than vice versa.

It’s a delicate and nuanced issue, and I feel my relationship with the camera and how the camera relates to the model needs to be advanced, but this is an ambition. This, in turn, may influence how I make subsequent models, perhaps broadening degrees of finish or expanding my use of found materials to introduce quiet “give-aways” within the photographs.

Charlie Stiven. Der Gefaulte Traum, 2016. Wood, acrylic, mixed media, 42 x 42 x 34 cm. Photo © The Artist.

JMcK: Can you describe the work Der Gefaulte Traum?

CS: Yes, the title of the work, Der Gefaulte Traum (The Fouled Dream), comes from a heading of an item in the German tabloid Bild, about the extramarital activities of a football personality. Bild is the best-selling tabloid in western Europe. It was founded in 1952, about 500 years after the invention of the Gutenberg printing press. I wanted the title of the work to transcend its original context and instead wished to prompt reflection on the distance from the original impact of the printed word – a revolution in the dissemination of information and knowledge – to what is often its purpose today, a dumbing-down distraction conveying nonsense, half-truths and no truth.

From the example of the newspaper kiosk, one can also extend this to the malevolent, distorting world of the internet. Within the piece, the newspapers, placed repetitively in the front of the structure and left discarded at the rear, are arranged to echo this ongoing, purposeful and never-ending stream of distraction. The base on which the newsstand sits is covered in dirt and detritus, reflecting the fact that fundamentals are neglected in the wake of the avalanche of “stuff” forced on us.

Structurally, the contrived construction of the kiosk follows certain principles of European modernist architecture and at the same time seeks to evoke a physical and metaphorical tension that resonates with the thematic – the structure has logic and cohesion but remains unsettled and ill at ease. This is intended to suggest that the pattern of behaviour described above has more as yet unforeseen and potentially uncontrollable consequences.

Charlie Stiven. Lviv, 2023. Wood, acrylic, mixed media, 16 x 16 x 18 cm each. Photo © The Artist.

JMcK: Between Two States (Lviv, Ukraine) has a melancholic and enigmatic message. Can you describe its significance?

CS: I visited Lviv just before lockdown to arrange an exhibition. Alas, due to Covid-19 and now the horrendous war, this hasn’t come to pass. Once a key hub within the Austro-Hungarian Empire and a constant centre of flux relating to Polish, German and Russian eras of dominance, Lviv sits in an uncertain position caught between times and forces – between a historic yet still present Russian influence alongside a wish by others to look towards western culture and markets. Economic, political and societal fragility have created an atmospheric of uncertainty and tension present in tangible and subliminal ways. Events since [Russia invaded Ukraine in] February 2022 have, of course, served to bring these tensions into sharp and tragic focus.

Charlie Stiven. Research image of street kiosk, Lviv, Ukraine. Photo © The Artist.

Many of the street kiosks I found in Lviv have a hybrid characteristic moulded by reference to Austro-Hungarian art nouveau architectural style and a functional Soviet era aesthetic, and, as such, I saw them as being like small encapsulations of multifaceted political and cultural influence – again, microcosms of history and circumstance. The Lviv models I made are, unusually, pretty direct replicas of certain kiosks I found there. These existing structures said all the above without the need for adaption. Their roofing echoed the massive art nouveau structure of Lviv’s central railway station, built in 1904, their drab colouration the claustrophobic atmospheric of Soviet functionalism, their semi-shuttered presence reflected the inscrutable tension I felt, and the graffitied Ukrainian symbol was painted as I found it.

JMcK: You continue to work in Europe. What impact has Brexit had on the life of artists in the UK?

CS: Well, it’s difficult to remain polite when considering this. The engineers of Brexit need locking up. It is truly awful, driven by a level of conceit and expediency that is barely credible, and it’s extremely depressing that so many people swallowed the myths and lies that led to it. The EU is far from perfect, and I have commented on this in previous work, but cutting ourselves off from our neighbours like this to follow such a shallow nationalistic (and dangerous) narrative is, frankly, scary. It does seem that people have very short memories or simply do not pay heed to the lessons of history (and are not encouraged to). Again, I try to counter this in aspects of my work.

It remains to be seen how the new government might attempt to soften the results of Brexit, but I feel the UK is in danger of being set back decades, psychologically and culturally. In relation to artists, it’s hard enough being an artist without the imposition of new barriers that prevent dialogue, expression and the cross-fertilisation of information, ideas and sensibilities.

I know through conversation that many gallerists in Europe now think twice about engaging with UK artists due to increased costs and bureaucracy. I have artist friends from the UK living in Europe who either fortunately managed to attain EU citizenship or had to return, and others who have had to limit periods abroad due to visa limitations. And, of course, working in higher education, I can see the restrictions on student learning and experiential opportunities in Europe.

All the above is well known and I could go on. I suppose if there is any potential positive side to this, it’s that artists continually react to and against things, responding to negativity in creative and stimulating ways, finding methods to work over and through things.

Let’s hope so.