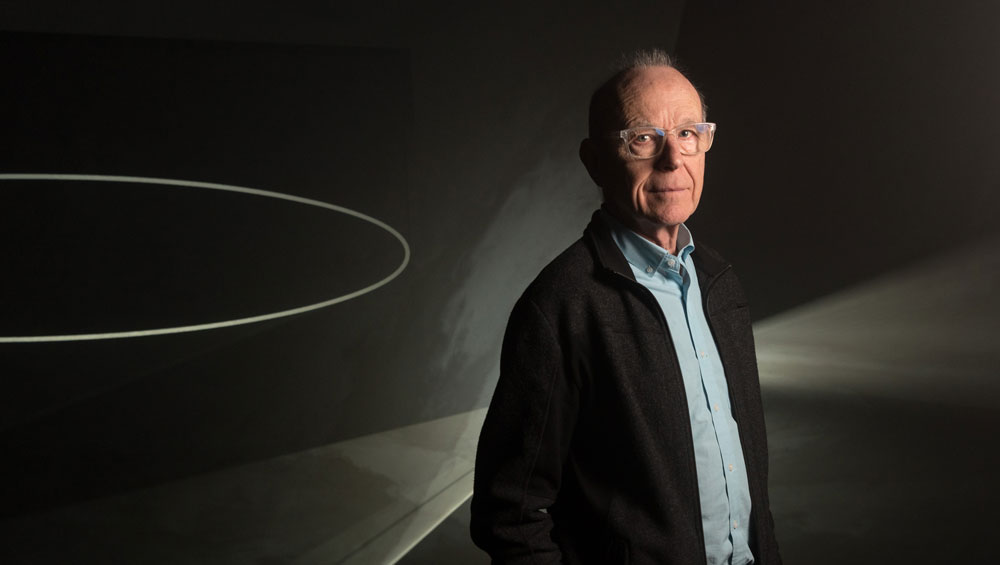

Portrait of Anthony McCall at Hepworth Wakefield. Photograph: Guzelian.

by JOE LLOYD

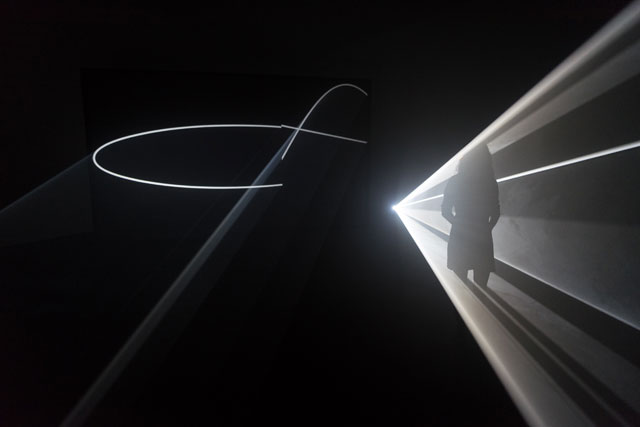

There is something of the magician in the solid light works of Anthony McCall (b1946, UK), currently the subject of a survey at Hepworth Wakefield. Created by projecting ever-shifting beams of light against a wall or floor, they grant uncanny sculptural qualities to that which is intangible. Haze machines augment them with a lustrous mist. Standing within these corridors of light is like being inside some strange astral plane. A simple hand movement can feel like stroking a waterfall or marshalling cosmic dust. The experience is undeniably seductive. “We cannot help,” wrote the critic Hal Foster in The Art-Architecture Complex, “but touch the light as though it were a solid and investigate the cone as if it were a sculpture – cannot help but move in, through and around the projection as though we were its partner, even its subject.”

Anthony McCall. Doubling Back, 2003. Installation view, LAC, Lugano, 2015. Photograph: Stefania Beretta.

The solid light works stand at a unique intersection of media. In their projection of a moving image, they are films, and yet they are experienced as three-dimensional, immersive environments. The projected images are line drawings, but drawings that move over time, in a constant state of flux. They are, on the one hand, deeply sensuous, marshalling light to awe-inspiring effect, and, on the other, cerebral exercises that make us question where exactly the artwork is. Is it in the projected image, or the effect it has on the space it inhabits? Or is it the participant themselves, whose every glance and movement defines their encounter with the installation?

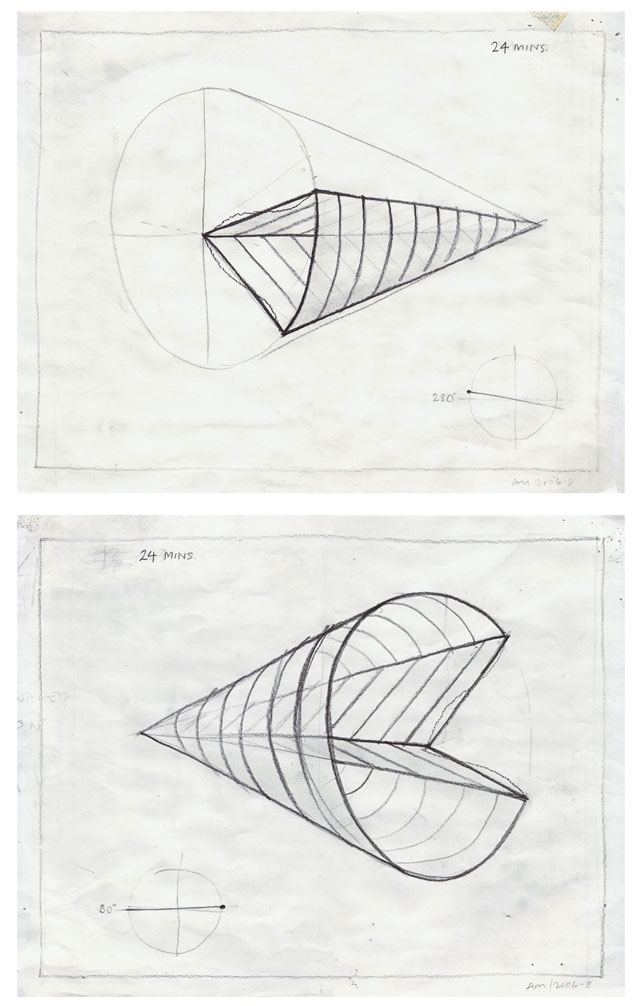

Anthony McCall. Leaving (with Two-Minute Silence), 2006/8. Pair of working drawings in a set of 24. Pencil on paper, each 28 x 35 cm.

McCall’s work began in 1960s London, where he participated in radical film groups and began experimenting with incorporeal materials. His early fire performances, documented in the exhibition, involved grid-like arrangements of fire being sequentially lit and quenched as if in a musical score. But it was Line Describing a Cone (1973), in which a single point of projected light gradually grew to form a complete circle, that provided the stepping-off point for much of his later oeuvre. Moving to New York towards the close of the 70s, he stopped practising until the turn of the millennium when, drawn to the potential of digital projection, he continued where he left off. These recent iterations apply the principle of Line Describing a Cone to more complicated patterns and rhythms. Although they operate with the same technology and principles, each one feels distinct, defined by the shapes its light draws.

Anthony McCall. Landscape for Fire II, 1972. 16mm lm still.

The exhibition at the Hepworth Wakefield, simply titled Solid Light Works, contains three such pieces: Doubling Back (2003), Leaving (With Two Minute Silence) (2009) and Face to Face (2013). All of them are premiering in the UK for the first time. It also gathers videos, photography, maquettes and drawing to create a fascinating portrait of McCall’s practice, homing in especially on the meticulous processes by which he plots his installations. They reveal McCall as more rational scientist than mere conjurer. And yet, ensconced within his luminescent projections, one feels transported out of this world. Art is seldom so numinous.

Joe Lloyd: How does the Hepworth Wakefield, a museum that specialises in sculpture, suit the installation of your solid light works?

Anthony McCall: I found the gallery spaces to be surprisingly sympathetic. The not-quite-square corners and the ceiling gradients seemed to take on whatever I placed in the spaces. Specifically, the radiating forms from each of the projectors found a sympathetic echo in the gently sloping ceilings.

Anthony McCall. Face to Face II, 2013. Installation view, Eye Film Museum, Amsterdam 2014. Photograph: Hans Wilschut.

JL: Given the precision of your work, what do you take into account when installing them?

AM: I have found over the years that the projection throw between the projector lens and the wall needs to be about 10 metres. This means that the tallest points of my radiating forms are not quite double human height, with the lowest point being barely a few centimetres: scale is based on the body rather than the architectural space. So the work is not site-specific. Still, it is site-sensitive and I spent quite a bit of time with the plans and sections of the building testing different orientations for the installations. I look for ways for the installation to directly address visitors as they emerge from the light-lock corridor and enter the dark room.

Installation view of Anthony McCall: Solid Light Works at Hepworth Wakefield. Photograph: Guzelian.

JL: What triggered your interest in working in a durational, time-dependent mode?

AM: As a young artist, I was drawn to performance, like my series of outdoor fire performances produced between 1972 and 1974. The volatile medium was petrol, a liquid that could be measured, so that burning times and spatial movements across a grid could be predicted. I found quite early on that I was essentially working with timing, and with sequential structure.

JL: Have drawings always been an integral part of your work and, if so, why? What relationship do they bear to a finished solid light work?

AM: Drawing is at the centre of my working process and, in fact, once a solid light work is realised as an installed work, drawing remains at the centre, in the form of the line-drawing – the “footprint” – that the projector casts on to the opposite wall.

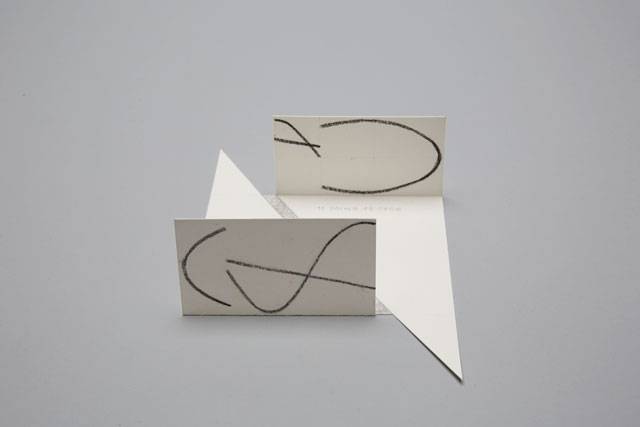

Anthony McCall. Face to Face II, 2013. Installation maquette. The Eye Museum, Amsterdam, 2014.

JL: An interesting facet of the exhibition is that it demonstrates, stage-by-stage, the process by which your pieces are created. Could you describe these stages?

AM: A work begins usually as a simple idea in my small notebook. I may move to a larger notebook in order to fully develop the idea. After that, and sometimes quite early on, I’ll work in parallel on different kinds of drawing: first, progressive, storyboard sequences of the two-dimensional “footprint” line-drawings; and second, simple perspectival renderings of the three-dimensional object in space.

These two different but complementary approaches may be expanded to larger sequences of individual drawings. For instance, in the exhibition, there is a set of 24 drawings for the installation Leaving, which combines storyboard and perspectival drawing. Once I am certain of the shape of a work, I will write this up as “instruction drawings” for my programmer. These are essentially notes and diagrams full of the essential details about what happens in the line drawings and how those lines move and change over time. Remember, the programmer only needs to know about what happens on the screen: the volumetric, sculptural aspects of a piece occur only at the moment of projection. This is when the haze in the air reveals the three-dimensional extension of the lines on the wall.

Installation view of Anthony McCall: Solid Light Works at Hepworth Wakefield. Photograph: Guzelian.

JL: The work in Wakefield is incredibly precise. Have you ever been interested in utilising chance?

AM: In order to utilise chance, you need a procedure. Quite often those procedures themselves require precision, and I’m not sure that precision and chance are necessarily opposing terms. In any case, a lot of counting has gone on in my preparatory work for performances like the 70s fire pieces, or almost any of the solid light works. I am mostly working with motion and with time, so the drawings necessarily have to freeze motion and freeze time. The drawings may be loose in style, but the underlying timing needs to be quite exact.

JL: I noticed that the pieces in the Hepworth have names that suggest human, even bodily, activity. What led you to move to these from your earlier, more simply descriptive titles?

AM: The titles for the 70s solid light works were matter-of-fact, such as Line Describing a Cone, Conical Solid, or Long Film for Four Projectors. The works since 2004 have alluded to states of exchange, such as Between You and I, Meeting You Halfway or Face to Face. This started in the early 2000s when I began looking again at the early solid light works like Cone of Variable Volume – another apparently purely descriptive title. When I looked this time, however, 25 years later, the volume changes of the conical projection looked unmistakably like breathing. This gave me a new starting place.

Installation view of Anthony McCall: Solid Light Works at Hepworth Wakefield. Photograph: Guzelian.

JL: The solid light works in the Hepworth are all horizontal, but you have also created vertical pieces. How does the experience of these differ?

AM: The dimensions of each are identical: a throw of 10 metres with a footprint about 4.3 metres

across. But, as experiences, they are very different. The sense of being surrounded and absorbed is stronger in the horizontally oriented works; and the presence of the projector and screen at a similar height to the body refers them back to cinema quite directly. The verticals – which I refer to as “standing figures” – reference sculpture, but also architecture in that they can be inhabited, and experienced as towering, tent-like forms that rise way above your head. Breaks in the membrane are read as doorways.

JL: What initially drew you to the cone-like forms?

AM: My notebooks from that period show many drawings of projected forms. They are always either flat blades of light or cones of light. Nothing else. The aspect ratio of a film frame was 4:3. I could have come up with a pyramid of light rather than a cone, I suppose, but I never did.

JL: During the tour of the exhibition, you described the solid light works as “films”. How do they interact with this medium?

AM: Yes, I often still refer to them as films. Obviously they no longer use the medium of film, but it is so much easier to call any one of them a film, as in “a work of cinema”. “Installation” is so general a term, and “solid-light installation” is too much of a mouthful to use often. The term “film” is not accurate, and it leaves out all the other ways you might describe these works, but it is modest and short.

JL: Your works both interact with architectural space and create the illusion of architectural space. What significance does architecture have for your work?

AM: Architecture is a hovering parallel universe. I rub shoulders with it when I plan an installation. I like it best when one can glimpse the architectural container from the dark spaces of the installation. And, sometimes, a solid light work directly engages the architectural space, like Doubling Back in this exhibition, where the forms furl and unfurl in a direct relationship with the adjacent wall and the floor. I explored this same orientation first in 1975 with Four Projected Movements, where a flat blade of light rotates into or away from the adjacent floor or into or away from the adjacent wall.

• Anthony McCall: Solid Light Works is at the Hepworth Wakefield, Yorkshire, until 3 June 2018. Additionally, recent works are on display at Sprüth Magers, London, until 31 March.