Ali Cherri at the National Gallery, London, 2022.

by JULIET RIX

The multimedia artist and film-maker Ali Cherri has spent the last year dividing his time between his permanent studio in Paris and his temporary studio at the National Gallery in London where has been artist in residence since May 2021. The fruits of this residency are now on display amid the gallery’s permanent collection, under the title If You Prick Us, Do We Not Bleed?.

Cherri was born in Beirut in 1976, the year after the start of the Lebanese civil war, which lasted into his mid-teens, and his work focuses on the way violence is “archived” in the body as well as in artefacts and museum collections. He examines how art and heritage institutions deal with the narratives of history and war, and the sub-cutaneous, subterranean and otherwise hidden effects of violence and trauma.

Nicholas Poussin (1594–1665). The Adoration of the Golden Calf, 1633-4. © The National Gallery, London.

For his residency and this exhibition, Cherri has chosen to focus on five famous paintings in the National Gallery collection – by Leonardo da Vinci, Diego Velázquez, Rembrandt, Nicolas Poussin and Federico Barocci – that have been damaged in the gallery by acts of vandalism, before being restored and put back on display without comment on what has happened to them.

Ali Cherri. Self Portrait at the Age of 63, after Rembrandt, 2022. Wax and metal frame. Wax head created by artist, Andrew Lacey. Commissioned by the National Gallery, London, as part of the 2021 National Gallery Artist in Residence programme. Photo: Juliet Rix.

Gabriele Finaldi, the director of the National Gallery, and Francis Nielsen, the director of this residency’s regional partner, the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum in Coventry, note in their foreword to the exhibition catalogue: “This is a topic upon which museum directors generally prefer not to remark,” their role being to protect and preserve the work in their care. They admit, however, that works on display to the public are inevitably vulnerable, adding that Cherri has explored the act of violence against art works in a “striking and thoughtful way”.

Cherri spoke to Studio International at the National Gallery as his residency work went on display.

Juliet Rix: How were you chosen for this one-year National Gallery residency?

Ali Cherri: You get invited to do this residency, you don’t apply for it. It’s an interesting selection process. The artists don’t know they are shortlisted. There’s a jury of six or seven members and each proposes two artists and presents for their artists. One is chosen and then they contact the artist offering the residency.

I received the invitation during the first lockdown, a very strange time when we didn’t know what the future would be. It was an amazing opportunity to have a studio at the National Gallery and produce new work. In the first wave of Covid when everyone was panicking, everything was cancelled and we didn’t even know what was going to happen tomorrow, it gave me hope for the future.

JR: How was it starting your residency?

AC: It was a bit intimidating coming to the National Gallery – though everyone was very welcoming and willing to give me time. You think, what can I add to this institution where you have the top-level specialists in every field? So, my entry point was not about this artwork or that painting, but to look more at institutional practice. That has always been part of my work, as well as an interest in the relationship between violence and the site of the museum. This comes from my personal experience. I was born in Beirut at the start of the civil war, and I lived there until I was 30. I lived through the war years, the reconstruction and the possibility or impossibility of telling the war story after trauma. These questions have always been of interest to me.

The role of the National Museum in Beirut is something I’ve worked on a lot. It was the only museum in Beirut at the time and it sits on the demarcation line between east and west where the city was divided, so the museum became a place where snipers and the militia took over. When I was growing up, the word “museum” meant the passage between east and west that ran along the side of the museum. We would say, “the museum is safe today, or the museum is closed” – meaning the passageway. I grew up with the “museum” changing states – closed, open, bombarded.

JR: The museum as a barometer of the state of things?

AC: Yes. And the museum itself became a ruin. I was interested in the idea of the museum, instead of just hosting the ruins of the past, itself becoming the ruin, and all the different levels of ruin that happen inside the museum – the museum as a political site and a sort of condensed collective history of trauma and violence.

The first time I set foot in the National Museum was right after the war. All the small items had been taken to different places to keep them safe and the larger sculptures and sarcophagi that could not be moved had been first surrounded with sand bags then, when the war became more violent, put into cement blocks. The first time the museum reopened, it was empty except for these large cement blocks with a small image that said: ‘Inside this block is …’ It was a question of faith – trusting the museum, that what was invisible was, in fact, safe inside the bunker.

When I first came to Europe, when I was about 25, and walked into a museum, it was a very different experience. But then I wondered, is it so very different? All works, sadly, can be vulnerable. We see what is happening in Ukraine today, with museum directors trying to protect their collections, sandbags around statues. It has happened in Iraq, in Syria, in Libya, even here at the National Gallery in the second world war.

JR: That’s a fascinating image – the museum works hidden inside the concrete; the opposite perhaps of what you are doing now? Then the artwork was hidden, while the wound – or the armour against it – was visible, on the outside. Now you are looking at the artwork and asking what is hidden beneath its surface?

AC: When I started to accept and speak about trauma, I started to look for these hidden wounds. I wasn’t injured during the war. I don’t have any traces to say: “I was in the war and here’s what happened to me.” Physically, I survived, but this term “survival” is very hard to accept. We talk a lot about resilience, but I think it is a very violent word. Resilience means getting over your wounds, not being affected by them. I don’t think we “survive”. We adapt, we change, we do something else, but we do not go back to normal.

JR: We absorb and learn to live with trauma, rather than overcoming it or it going away?

AC: Yes, exactly. This was a trigger for me here at the National Gallery. I did not have a preconceived idea of what I would do here, but I was looking for stories I could relate to. I knew about only one of the vandalised paintings – The Rokeby Venus (The Toilet of Venus by Diego Velázquez, 1647-51, slashed several times by the suffragette Mary Richardson in 1914). When I started looking in the archives, it turned out there were many vandalised paintings.

Diego Velázquez. The Toilet of Venus (The Rokeby Venus), 1647-51. © The National Gallery, London.

I started looking at these canvases, these images that were “hurt”. I give it the sort of adjectives that we give to humans, but that isn’t just me. The newspapers [at the time of the attacks] talked about “bruises” and “wounds”. They described how the Leonardo (The Virgin and Child with St Anne and the Infant St John the Baptist, “The Burlington House Cartoon”, c1499-1500, shot with a sawn-off shotgun in the gallery in 1987) was carried like a dead body to the restoration department. Whenever these artworks become fragile or vulnerable because of an attack, they suddenly become like living beings – or at least we relate to them like living beings that we have to protect and take care of. So this entry point was obvious for me – it spoke to my previous work, my history, my personal experience. I felt this was somewhere that maybe I had something to add to the discussion.

Leonardo da Vinci. The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and the Infant Saint John the Baptist (The Burlington House Cartoon), about 1499-1500.

JR: What did you decide to do with the vandalised paintings?

AC: I selected the five that I was most intrigued by, and, for each picture, I created a vitrine. Most are vintage cabinets from other museums – one is from the V&A, one from the National Maritime Museum – so they also come with their own history. And they bring the idea of the “cabinet of curiosity” and of colonial museums. The National Gallery is a museum that does not usually have vitrines. And the vitrine is also a contained space, framing the work but not on the wall. I thought, I cannot compete with what is on the wall.

JR: However great an artist you are, it is tough to compete with Leonardo and Rembrandt …

AC: Yes! So I wanted to occupy the empty spaces between the masterpieces. Framing the work, but not on the wall.

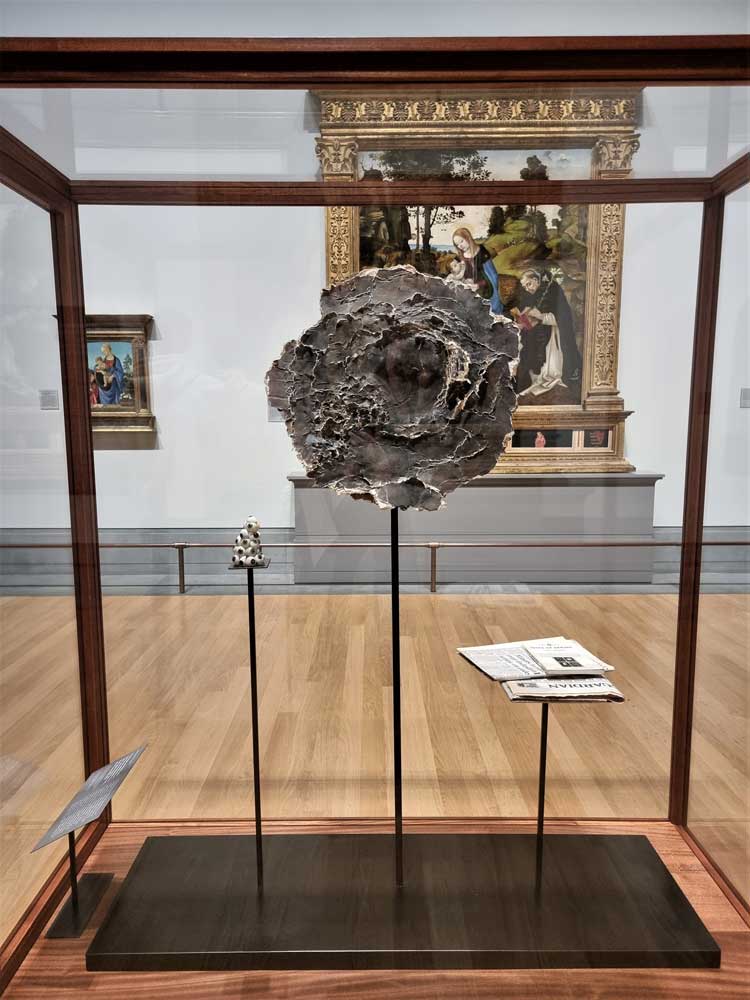

Ali Cherri. The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and the Infant Saint John the Baptist (The Burlington House Cartoon), after Leonardo, 2022. Cardboard, glass eyes, newspapers (The Independent, The Times, and The Guardian from 17 July 1987) and a book (John Berger, Ways of Seeing). Commissioned by the National Gallery, London, as part of the 2021 National Gallery Artist in Residence programme. Photo: Juliet Rix.

JR: How did you decide where to put the vitrines? As you look at the contents, you are also seeing through to the paintings on the walls beyond, so I’m guessing you chose their positions quite carefully?

AC: I was able to choose where I wanted the work to be. Naturally, the first thought was to have them next to the damaged paintings, but then discussing it with the curator, Priyesh Mistry, we thought we should take them away from these paintings, so we were not comparing the vitrine directly to the artwork, and place them in the Sainsbury Wing, where the iconography speaks more to the project I’m trying to do. It’s where we see all the Christian iconography. The wound is very present. One of the cabinets – for the Leonardo – sits right in front of the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (by Antonio and Piero del Pollaiuolo, 1470s). I am asking the question, what wounds are allowed to be seen in the museum and what wounds have been made invisible? I wanted to create this dialogue. There is some very violent imagery in the gallery, but other kinds of violence have to be completely out of the narrative.

Installation view, Ali Cherri: If You Prick Us, Do We Not Bleed?, the National Gallery, London, 2022. Photo: The National Gallery, London.

JR: Such as the violence against the vandalised paintings?

AC: The museum is the caretaker of this collection, and its role is to protect and to present the work in the best light, so it is the policy of the museum that it never publicises these attacks or shows any image of the damage to the painting. It is understandable; it does not want copycats. It sometimes does a very short press release at the time, but some attacks the public never even know about. On the labels next to the paintings, there is no mention. Maybe we should mention this. This is part of the life of these works. What I am trying to argue is that you cannot un-write violence – you cannot think that this never happened. We repair, but we have to acknowledge that violence happened because violence changes something in the core of who we are. I’m not saying we are always broken. We find other ways of life, and that’s beautiful, but we cannot erase it.

JR: I suppose it is reasonable that the gallery is reluctant to give publicity to the vandals or their causes, in case, as you say, it encourages others.

AC: Yes, it is a tricky line. I understand the position of the gallery. That is why there is little mention in my work and publications of the details of the attackers. I am more interested in what happens to the artwork afterwards; how the museum deals with them. My focus is on the “victims”.

I had a very interesting conversation with Gabriele [Finaldi], who mentioned how, now that it is more than 100 years since the attack on the Rokeby Venus, the paint that was used to restore it is aging differently [from the surrounding paint] so, all of a sudden, the slashes are more visible than they were 50 years ago. Without doing psychoanalysis: however well these wounds were repaired, 100 years later they start to resurface.

My work is really focused on material manifestation of violence. I look at how violence can be inscribed in landscapes, how it can infiltrate the earth, the trees, the bodies of people. Currently, I’m working on a feature film called The Dam, shot in northern Sudan on a hydroelectric dam on the Nile. The building of the dam was very destructive to nature, and many people had to be relocated. It was a very violent construction, but today when you go there, there is just this beautiful lake. There is nothing [of the destruction] visible. I am trying, in this film, to look at the hidden traces of this violence – how it’s still inscribed in the landscape and the elements, even if it isn’t visible.

JR: You did some work on a similar theme looking at the seismic faultlines below the surface of the ground in Lebanon.

AC: Yes. That film is called The Disquiet and it is about how it feels to live on earth that has unrest under it. Of course, it is a metaphor for the political unrest. I come from a region that has seen crisis after crisis – and you see what is happening in Lebanon today. It speaks of this constant unrest and the body as a seismograph that registers this. The film opens with the sentence – which is true – that every day there are 60 tremors in Lebanon, but nobody feels them because they are very small. But I finish with, “but I feel every single one”. Sometimes, we are not aware, but our body is registering all these little tremors.

JR: Having chosen your five “hurt” pictures, how did you decide what to put in the vitrines for each painting? For instance, with the Leonardo, you have taken the “bruise’’, the gunshot “wound”, expanded it and made it the centre of your display. Then you have added a couple of newspapers from the day of the attack, a little pyramid of glass eyes, and a copy of John Berger’s seminal book Ways of Seeing.

AC: The artist’s bible. Every artist has at some time looked at this book and it has changed their way of seeing.

I use the cabinets a bit like when you create a kind of talisman - when you put things together for magic, for something to happen. I wanted to enlarge the [gunshot] wound so it becomes like a sun, like an eye, like something abstract, something glorious even, to show the wound and accept that it is there. And whatever is around it is taking care of it.

The question of the gaze has always been interesting to me. You do not only look, but are looked at inside the museum. The prosthetic eyes are from the 19th century and were used for people who had lost an eye, to replace the eye. They are organs that do not see, but allow us to look as if we can see again. Whenever you turn around, there are eyes looking at you that make you conscious that we are also being looked at, as well as looking, in this space.

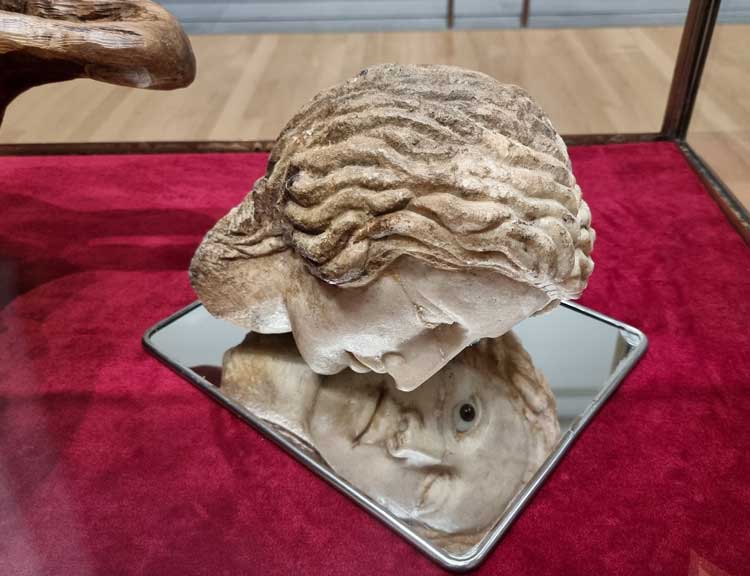

Ali Cherri. The Toilet of Venus, (The Rokeby Venus), after Velázquez, 2022. 19th-century marble head, wood, glass eye and velvet. Commissioned by the National Gallery, London, as part of the 2021 National Gallery Artist in Residence programme. Photo: Juliet Rix.

JR: I notice that in the vitrine for the Rokeby Venus, you have an antique-style marble head looking into a mirror and the eye is looking right back out at the viewer. Presumably that is linked to this theme too?

AC: Yes, and it is also taken from what Velázquez was doing in the Rokeby Venus. I think his is a very modern interpretation of a classical subject. Velázquez put the mirror where Venus is looking at herself in the centre of the painting and Venus is not looking at us but is looking at herself, giving us her back. It is empowering. She is self-sufficient, she does not need us. We can only look at her through this mirror that is a bit out of focus, a bit hazy, telling us we can never really know who that woman is. I think it’s a very modern, empowering way to present the female body. I wanted to take the modernity of the Velázquez and go to something more archaic. The body I chose to put on display [with the marble head] is a model of a 45,000-year-old fetish that was found in Germany. It is also called Venus because all fetishes, female figures, at least in the western world, are called Venus, so it is a 45,000-year-old Venus. I recreated it, oversized, in wood (the original was in bone) with all the scarifications that were on the original, which could be rituals or maybe beauty alterations. What violence did to the painting – to Velázquez’s Venus – takes it back to something more primordial. If you attack a son or daughter, the mother is going to fight like an animal. There is something about violence that brings out the primeval.

Ali Cherri. The Toilet of Venus, (The Rokeby Venus), after Velázquez, 2022. 19th-century marble head, wood, glass eye and velvet. Commissioned by the National Gallery, London, as part of the 2021 National Gallery Artist in Residence programme. Photo: The National Gallery, London.

JR: The modernity of the original Velázquez makes it a particularly interesting choice for the suffragette Mary Richardson to have attacked in 1914, and she very specifically damaged the body of Venus, didn’t she?

AC: Though it doesn’t form part of my display, I was very interested in the police reports and how people described why they made these gestures. With the suffragette, it was clearly a political act, a protest against the arrest of one of the suffragettes (Emmeline Pankhurst) but also, [Richardson] said it was about how men “gaped all day” at the body of Venus, drooling, so she gave this also as a reason – the male gaze on this body, a different kind of patriarchy and violence on a woman’s body. She said they were destroying the most beautiful woman in politics (the suffragette), so she was going to destroy their most beautiful woman.

Federico Barocci (about 1533–1612). The Madonna of the Cat (‘La Madonna del Gatto’), probably about 1575. © The National Gallery, London.

JR: Tell me about the contents of your vitrine for Barocci’s Madonna and Child with St Joseph and the Infant Baptist (“La Madonna del Gatto”, c1575). You have created a striking sculpture of a pure white hand over a real (stuffed) goldfinch.

AC: I was interested in the hand gestures in the painting where we have the Madonna’s hand open and the infant St John holding the goldfinch. In Christian iconography, the goldfinch got the red patch on its head from blood from Jesus on the cross that fell on it.

Ali Cherri. The Madonna of the Cat, after Barocci, 2022. © Ali Cherri. Photo: The National Gallery, London.

JR: A visualisation of wounds incorporated in a way that is not damaging?

AC: Yes. It is a more beautiful bird because of the blood it received on its head. I find this a very poetic image. And a very beautiful image of retaining and releasing – the two hand gestures in the painting, and the goldfinch that is trapped but we know will be saved. I wanted to recreate this with the oversized, very classic hand in white porcelain that is both trapping the bird and caressing it. So there is this duality of violence and sensuality in the gesture of the hand and we don’t know if the bird is hurt and the hand is going to take care of it or it is the hand that is completely trapping it. It’s working on this thin line of beauty and violence that can be in the same work.

JR: Do you think that museums need to change the way they deal with violence and trauma within the works they display?

AC: I think I was invited here to create a dialogue. There were lots of negotiations during the creation of this show, with the directors, the conservators, the curators, because it’s a sensitive topic. They said yes, this you can do, and no, this we cannot do. There was a lot of discussion, so whenever I walk past the staff, they have something to say about it. It has put this on the table. Before, everyone agreed on the policy – we do not show this, we do not talk about it, it is not part of our narrative. Now, I am here, and they have accepted that I’ve opened this topic and it is out there and we are here today discussing it. I’m not saying what the museum should do, but I know my role in what I have been doing. It has opened the conversation.

JR: We have talked about the influence on you of the conditions in which you grew up and the role of the museum, but what about artistic influences. Are there any artists who have been particularly important to you?

AC: The postwar period in Beirut was a very rich artistic period. There were lots of artists in the generation before me who became very well known, such as Walid Raad, Akram Zaatari, Lina Majdalanie and Rabih Mroué. All these people were working in postwar Beirut, trying to think about the possibility of reconstruction. I was much younger, but I was very close. They were my first encounters with art. I didn’t go to art school, so my first-hand education was hanging around and seeing their work and their shows.

JR: You work in a variety of media – video, photography, drawing and sculpture. How do you decide which to use when you have a particular thing to express?

AC: I come from moving images. I consider myself a video artist and film-maker. I think in terms of images in time, or objects in time. Even when I do a sculptural work, as here, I am still thinking of the spatial experience, such as how we walk in, what we see first, how it is in relation to the space. Even static objects are placed on a timeline. My head functions like this. Then it is responding to context. And sometimes I think I haven’t done a film for a long time and I feel like working with film. It’s intuitive.

Ali Cherri. Still from The Digger, 2015. HD video, colour, sound, 24 min. Arabic and Pashto with English subtitles. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Image Farès, Paris.

JR: What next?

AC: I am part of the Venice Biennale, in the main exhibition in the Arsenale. It’s a new project of a three-channel video, cultural pieces and drawings. And I’m finishing the fiction feature film The Dam. It’s the third of a trilogy with The Disquiet and The Digger that all look at material manifestation of history in landscape. We should soon start sending that for festival consideration.

Ali Cherri. Still from Somniculus, 2017. HD video, colour, sound

14 min 40 sec.

JR: Finally, although perhaps at times with some ambivalence, you do seem to see museums as a place of refuge and coming together, a place with at least the potential to help us towards a collective understanding of our past. You have compared museum artefacts to human refugees, finding a place of safety though in the process changed by being taken out of context.

AC: Yes, I did a work called Somniculus, about this idea of inhabiting the museum. It’s a video shot in different museums in Paris. You see this person roaming at night in the museums, which could also remind us of someone sneaking in to sleep on a bench, finding refuge. This was the first film I filmed in Paris. I felt this was somewhere I had a right to enter, that a place I could enter this city with my work was via the museum. The museum is a space where, if you are a stranger, you are accepted. We are all tourists and strangers inside a museum. I like that. We don’t know who is coming from where. You can easily blend in inside a museum – belonging and questioning belonging. It can melt us all together.

• Ali Cherri: If You Prick Us, Do We Not Bleed? is at the National Gallery, London, until 12 June 2022. Cherri’s work will also feature at this year’s Venice Biennale, The Milk of Dreams, which runs from 23 April to 27 November.

Ali Cherri. Still from Somniculus, 2017. HD video, colour, sound

14 min 40 sec.