Barbican Art Gallery, London

3 May–12 August 2012

by REBECCA WRIGHT

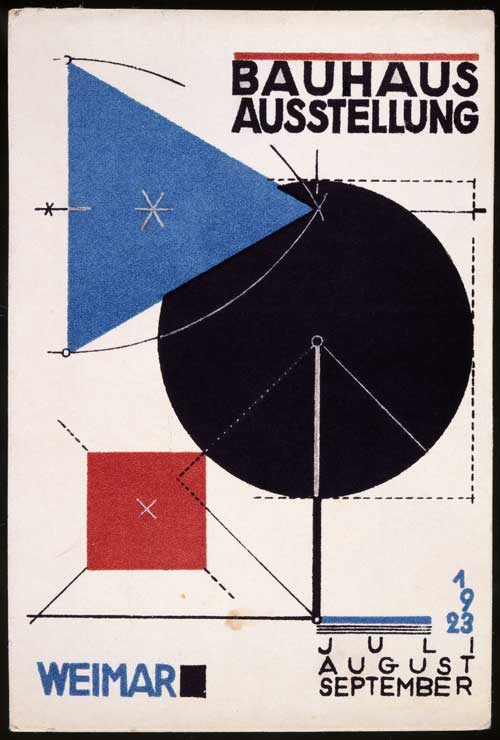

Herbert Bayer. Postcard no. 11 for the Bauhaus exhibition in Weimar, Summer, 1923. Colour lithograph on cardboard. Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. Photograph: Markus Hawlik.

This comment, which ties both the Olympic games and the Bauhaus movement together via some unfounded and vague notion of “idealism”, “internationalism” and “creativity” belies another facet that both the Olympic Games and the Bauhaus tentatively share in common; the power of advertising. For as the Barbican Gallery exhibition so brilliantly illustrates, under the standard “universal” Bauhaus typographic font was a school as diverse and eclectic as they come. If the Bauhaus stands at the pinnacle of high modernism, like a beautifully aligned font or corporate symbol, depicted within the Barbican exhibition (the first on the Bauhaus in England since 1968) is a community obfuscated by its nominalisation; which loved, fought, conflicted, partied, reprimanded, ate, drank, left, arrived and most of all questioned.

It is no surprise then that the Bauhaus have been so well branded as an artistic movement, for this was critical both to their functioning and to their academic programme. The consolidation of an easily communicated and recognisable aesthetic was central to the Bauhaus involvement and interaction with industrial design, and brought revenue and prestige to the school. An essay included in the catalogue by Catherine Ince entitled Spread the Word: Bauhaus Instruments of Communication details the pressure on the school to think about their own publicity and promotion.

She describes the Katalog der Muster (Catalogue of Designs) designed by Herbert Bayer, which followed the principles of the New Typography to detail the rigorous design principles and product coding needed to market these diverse products.2 Packaging the group in this way was not only the role of those involved in the Bauhaus Verlag (the Bauhaus press), but alongside this the Bauhaus campus, designed by Walter Gropius' private practice in 1924 in the new location of Dessau, physically wrapped the school in a particular Bauhaus aesthetic. The glass-fronted building acted as a stage in which one could see the cogs of the building, (in this case the students in the workshop), participating in the grand Bauhaus ideal. The new Bauhaus building, then, later became the ur-model of high-modernism, assimilating all the practices that happened there-within to that project. However, in opposition to this packaging, within the Barbican exhibition the tension between the Bauhaus' facade and its contents is once again re-activated.

In the exhibition we are lead chronologically through the history of the Bauhaus. We begin in Weimer in 1919, at the founding of the school by Walter Gropius under his leitmotif “Art and Technology: A New Unity”. We then follow its move to Dessau in 1924 and its change under the new directorship of Hannes Meyer in 1928. Finally we are lead to its dissolution in 1933 due to ongoing financial pressures and the threat from National Socialism. In each of these chronological time periods, various activities and influences are brought to the fore and segmented. Often these practices appear unrelated, such as a section containing both Oskar Schlemmer's large theatre costumes for The Triadic Ballet (1922), and elegant functionalist furniture like Marcel Breuer Club Chair (1925) and Josef Albers' Set of Stacking Tables (1927). This, at times is overwhelming, due to the sheer amount of participants included and the eclectic mixture of material. Apart from the chronological history depicted, one has to work hard to create a unifying narrative more sophisticated than that of “all this was created within the Bauhaus!”.

However, within this panoply of materials, individual narratives are brought to the fore and a texture other than that of the shiny white modernist finish emerges. The photographs taken by T. Lux Feininger, such as Women's Gymnastics with Karla Grosch on the Roof of the Prellerhaus (1930), and The Jump Over the Bauhaus/Sport at the Bauhaus (1927) reveal the daily life of school. The young photographer Feininger, (only 16-years-old when he enrolled in the Bauhaus in 1926), unconcerned (unlike many of his peers) with medium specificity captures the sense of fun so often left out of the hegemonic modernist narrative.

In images such as the Members of the Bauhaus Band, the whole image appears to sway along with the music produced by the dancer Xanti Schawinsky and the banjo player Clemens Röseler. As Philip Ursprung notes in his essay on Feininger, an illusion is created in which “the photographer and even the camera are driven by the music and have started to dance”.3 So not only are we introduced in the exhibition to the every-day life of the school but a sensual feeling of place is also evoked; in particular the strong smell of pungent garlic said to overwhelm the school. This suffocating odour of garlic is a central topic of an essay included in the catalogue entitled In the Bauhaus Kitchen by Nicholas Fox Weber. The reason why the school smelled of garlic, Fox Weber explains, was principally because a faction of the students led by Johannes Itten who adhered to the Mazdaznan doctrine, (drawn from the teaching of Zoroaster) strictly upheld the practice of vegetarianism. Though this diet did not last long, it illustrates how food, like everything else at the Bauhaus, was a space of creativity and freedom.4 Looking at the photograph View of The Canteen Terrace (1927) taken by Irene and Herbert Bayer, not only do we see the remains of the recent meal, but we also hear the busy clamour and clatter of plates from within the bustling canteen inside. The noise and smell of Bauhaus is conjured.

A motto thus written by Itten, “play becomes party – part becomes work – work becomes play” also illustrates how the sensual aspect of Bauhaus life was not separated from the work done at the school. Photographs drawn from parties as diverse as The Metal Party, The White Party, and The Beard Nose Heart Party attest to this model, capturing the overall effect of the legendary celebrations as a complete Gesamtkunstwerke. During these festivities Gropius, otherwise known as “great-chief”, “Gropi” or “Pius”, was inundated with gifts as diverse as a cannon for defending the Bauhaus (1924), and a cactus built of cucumbers which had flowers made from chocolate radishes (1926).5

Although due to their perishable nature these particular gifts were not kept for prosperity, the inclusion in the exhibition of other objects and documents related to these celebration generate new narratives about the Bauhaus. For example, as children's toys and rag dolls designed by Alma Buscha (1923) stand out within the show against more formalised Bauhaus design work, the importance of female students who have often been excluded from the history of the Bauhaus emerge as central to the life of the school. It is no surprise that Anja Baumhoff’s catalogue essay Female Careers at the Bauhaus documents the central role female figures such as Gunta Stölzl, Marianne Brandt and Alma Buscha held within the community, which though accepting of women, was still ultimately dominated by men. In this exhibition, looking not only at the Bauhaus products but the objects used in other Bauhaus scenarios upsets a singular Bauhaus narrative and opens up this history to unfamiliar figures and voices that previously have been neglected.

What becomes apparent is that it is was the people, (the students as much as the staff), that were central to the success of the Bauhaus. Though the Bauhaus font-type was central in the financial and economic success of the school, behind it was a community which, much of the time, stunk of garlic. This exhibition demonstrates that, after all, a name is just as important for what it doesn't signify as much as for what it does. When the National Socialists threatened the Bauhaus survival in 1933, leading the faculty to unanimously decide to dissolve the school, it was the people who emigrated (mainly to the US, France, Russia and Britain) who carried with them the spirit of the school, not the architectural structure in which it was housed. As this exhibition so clearly illustrates then, the Bauhaus exists as much in its messy and overwhelming contents as it does in its sleek manufactured facade, which too often (like the Olympic rings), stands in for an unlimited amount of narratives, stories, smells, sounds and ideas. The exhibition shows therefore, that just as it would be impossible to take the Bauhaus out of the people, it is impossible to take the people out of the Bauhaus.

References

1. Kate Bush, 'Forward and Acknowledgements', in J. Desorgues et al., Bauhaus, art as life [on the occasion of the Exhibition Bauhaus: Art as Life, 3 May–12 August 2012, Barbican Art Gallery, Barbican Centre],” 2012. p. 6.

2.Catherine Ince, 'Spread the Words Bauhaus Instruments of Communication', in J. Desorgues et al., Bauhaus, art as life [on the occasion of the Exhibition Bauhaus: Art as Life, 3 May–12 August 2012, Barbican Art Gallery, Barbican Centre],” 2012. p. 113.

3. Philip Ursprung, Art as Lifestyle Theodore Lux Feininger's Photographs of the Bauhauslers', in J. Desorgues et al., Bauhaus, art as life [on the occasion of the Exhibition Bauhaus: Art as Life, 3 May–12 August 2012, Barbican Art Gallery, Barbican Centre],” 2012.p. 149.

4. Nicholas Fox Weber, 'In the Bauhaus Kitchen', in J. Desorgues et al., Bauhaus, art as life [on the occasion of the Exhibition Bauhaus: Art as Life, 3 May–12 August 2012, Barbican Art Gallery, Barbican Centre],” 2012. p. 184.

5. Klaus Weber, '“Square & Flower: A New Unity”, Bauhaus Celebrations and Bauhaus Gifts', inJ. Desorgues et al., Bauhaus, art as life [on the occasion of the Exhibition Bauhaus: Art as Life, 3 May–12 August 2012, Barbican Art Gallery, Barbican Centre],” 2012. p. 165.