Phoebe Cunningham. I am One With the People, 2018.

Whitstable, England

2 – 10 June 2018

by EMILY SPICER

Whitstable is small seaside town on Kent’s north coast, a 20-minute drive from Canterbury, famous for its oysters and as charmingly briny a place as you could hope to visit. Crooked, ice-cream-coloured houses line the shingle beaches, and small fishing boats gather in the shelter of the walled harbour. Fish bars on the harbour and along the high street offer every fruit de mer that the North Sea has to offer. This is a place of abundance and occasional eccentricity, a place that perfectly lends itself to a particular type of art festival, one that makes every exhibit feel like a happy discovery.

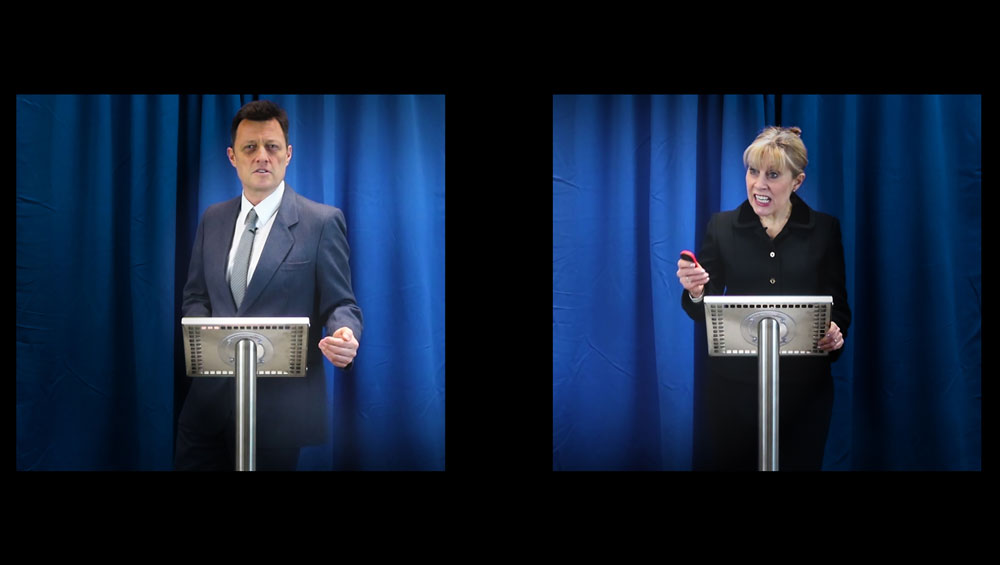

Let’s start in the public library with Phoebe Cunningham’s video installation I Am One With the People. By repurposing snippets from films and TV scripts, Cunningham has built new characters, which become increasingly unhinged over the course of the 10-minute film. It begins in the spirit of a leadership debate, albeit an offbeat one. Two politicians, a woman who is loosely based on Theresa May, but could be almost any white female politician – so precisely has Cunningham nailed the stereotype – occupies the right-hand screen, while a distinctly Kennedy-esque man in a suit speaks from the left. At first, they seem to be reeling out cliched attacks on the opposition, but soon the dialogue descends into melodramatic outpourings of hatred and jealously. “How do you know what a pretty girl wants?” the woman says scornfully, as this new soap-opera narrative emerges. The male politician starts on his tirade: “You are not even human beings… you are nothing but amphibian crap!” (An adaptation of a quote from Stanley Kubrick’s film Full Metal Jacket). With this, the professional veil is lifted to reveal tabloid personalities, which falter on occasion, in what seems to be scripted outtakes. It is strangely engrossing, and, given the behaviour of some our current politicians, not entirely without precedence.

Therese Henningsen. Slow Delay, 2018. Film, 17 mins.

Therese Henningsen’s film Slow Delay is screened at the Horsebridge Arts Centre cinema as part of the short-film programme. A mini-documentary of sorts, it follows two elderly brothers as they attempt to fix various parts of their dilapidated house. When they are not tinkering with sash windows or trying to start their antiquated motorbike, they sit in their tattered armchairs and question Henningsen on her life. Does she have a boyfriend, they ask. No. “Don’t you like boys?” The artist gives a quiet affirmation and one of the brothers lets out an unbelievably dirty laugh. They are dressed identically in black V-neck jumpers with yellow T-shirts beneath, and are, by their own admission, never apart. “Why did you let me in?” Henningsen probes. “I wanted a bit,” the man on the right explains, “but you weren’t offering.” She asks what it was he wanted. “Something you’ve got… down below,” is the unsettling response. There is a long pause as the man smacks his lips and a clock ticks loudly in the background.

Salma Ashraf. Chalta Hi Gaya, 2017. Two-screen film installation, approx 14 mins, loop.

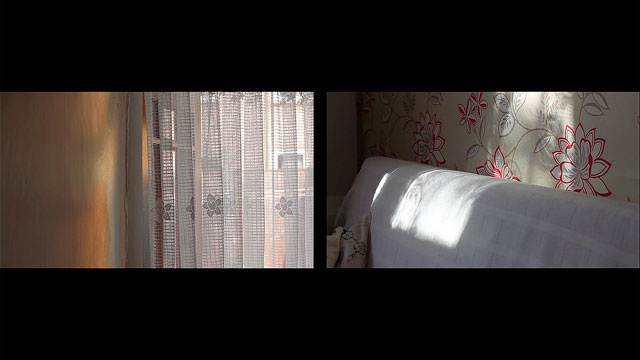

We enter a very different domestic setting in the back of Whitstable Museum. To reach Salma Ashraf’s film you have must first negotiate the merry assortment of local treasures, many of which look as though they have been dredged from the seabed by fishing nets – it is full of fascinating knick-knacks. Chalta Hi Gaya eavesdrops on the domestic life of two British Muslim women. The dialogue is selectively subtitled and we learn, through their conversation (we never see the women themselves) about life beyond the closed curtains. The camera focuses on corners of the house, the drapes at the window and the mantelpiece. The feeling is of one of besiegement as talk turns to the government-ordained Prevent scheme, an anti-radicalisation policy implemented in schools – a little boy is reported for speaking Arabic and having a toy gun at home – and of being singled out at airports. Gently, but unsettlingly, this film paints a picture of a hostile, neurotic world beyond the walls of the house.

In the bell tower of St Alphege church, Sophie Lee’s sound piece, Amore Tremor, acts as an auditory cocoon, another refuge from the madness outside. Our world is a noisy place before birth, the mother’s heartbeat and the sound of her voice is amplified in the womb and it is thought that this constant din is a comfort to the foetus. On being born, Lee tells me, we are exposed to the trauma of silence, an idea that offers an interesting inversion of adult life. In the entrance to the bell tower, she recreates a prenatal soundscape, bringing together church bells and club beats with compositions by the 12th-century nun and mystic Hildegard von Bingen, who, among other things, wrote the first account of the female orgasm. It is the kind of space that encourages you to close your eyes, to let the sounds carry you, if not back to the womb, then certainly somewhere other.

Turn right out of the church and you will reach Spoon Web, possibly Kent’s last DVD shop. Inside this compendium of comic collectables and out-of-date technology, tucked into a narrow alcove, is Rosie Carr’s film The Photocopier Who Fell in Love With Me. A woman’s voice addresses the object of her affection, celebrating its “papery respiration”. The comic-tragic narration continues “You’re so organised… you’re the only one who understands me… machine love is clean. Machine love fits my schedule.” Bored and lonely in an office where the only thing she can relate to is a whirring box in the corner, this woman’s predicament could be taken as a cautionary tale, a warning about what might happen if you let your imagination run wild while bored at work.

Patrick Cole. Restaurant, 2018. Live performance, 30 mins.

At the back of Whitstable’s Labour Club, in a multipurpose room adorned with the photographs of Betty Boothroyd and Jeremy Corbyn, performance artist Patrick Cole has built a set that evokes a grimy restaurant. Against this backdrop, a story of isolation and anxiety unfolds, culminating – via a strange tale about a goldfish – with Cole donning a heavily stained sheet, with two holes cut out for eyes. It is absurd, funny and strangely captivating, and like much of this festival, will stay with me for some time.