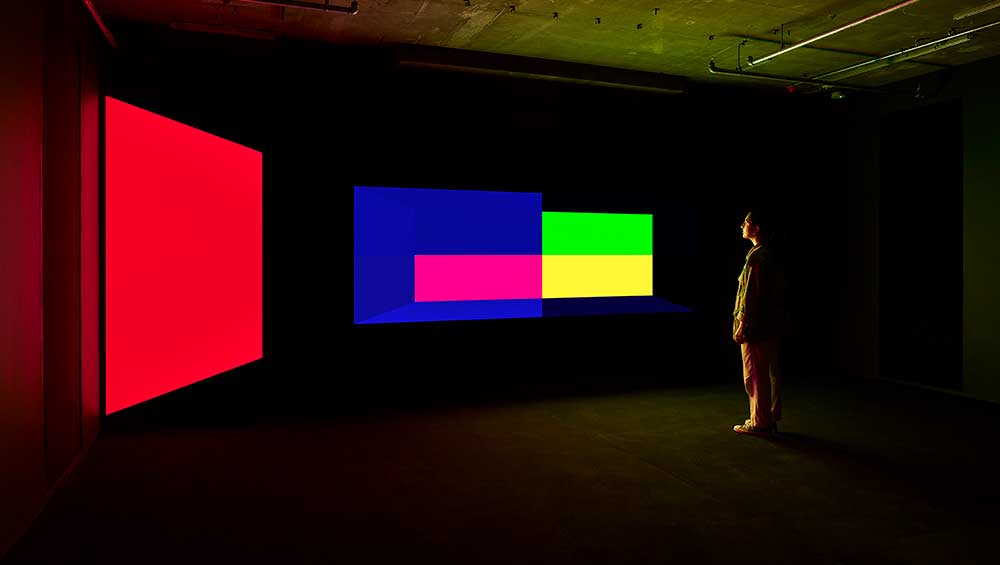

UVA, Chromatic, 2023. Installation view, UVA Synchronicity, 180 Studios. Commissioned by 180 Studios. Photo: Jack Hems.

180 Studios, London

12 October – 30 December 2023 (extended until 25 February 2024)

by BRONAĊ FERRAN

I head for the Strand in London to review a “survey” exhibition, featuring eight works by the London-based group United Visual Artists (UVA), organised to mark its 20th year. Co-founded by artist Matt Clark – along with Chris Bird and Ash Nehru, who have since moved on – UVA has become internationally recognised for dynamic event- and time-based installations often in site-specific locations. Close to the heart of the group’s practice is the manipulation and sculpting of light as a primary medium or material, with scores commissioned from a variety of composers that they combine with collaborative texts and electrifying visuals into stunningly multisensory assemblages.

Making large-scale public works with what are, in effect, immaterial media, combining light (and shadow) with moving data fields, along with striking sound compositions, creating a meaningful interplay of these elements that can shift perception of content and context together, is now UVA’s signature. So, too, a synchronous working of past into present in the spirit of ever-evolving processes in a narrative underpinning this new exhibition, that plays in iterative ways with works from UVA’s oeuvre and reconfigures these in the light of the shifting present. Indeed, five of the eight works on display are new commissions supported by 180 Studios.

180 Studios, London, exterior. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

The refurbishment of the Brutalist building 180 The Strand, which was constructed in the 1970s but subsequently fell into disuse, is a contributing factor (along with the pedestrianisation of the area) to an extraordinary recent extension of the cultural reach and offer of this previously neglected corner of central London. In turn, the building is a growing magnet for creative businesses – including art galleries, co-working spaces, design and digital production studios, restaurants, health and lifestyle facilities, fashion companies, publishers and various networking initiatives. Signs of its heightened cultural capital include the opening of a Soho House offshoot combined with rooftop swimming pool, plus Frieze and Charlotte Tilbury have recently moved their offices here.

On the day of my visit, the buzz around the building’s front door was about the Gucci Cosmos exhibition, involving 3D display techniques, now on in the upstairs gallery spaces. Round the corner in Surrey Street, running from the Strand to the Thames embankment, is the entrance to what have been described as the “subterranean” spaces where UVA’S new Synchronicity exhibition is situated. The refurbished building that dominates the left-hand side of the street forms a singularly late-modernist visual counterpoint to the art nouveau frontage of the now closed Strand underground station opposite. Both inside and outside the galleries, therefore, there is a sense of a continuum from past to present.

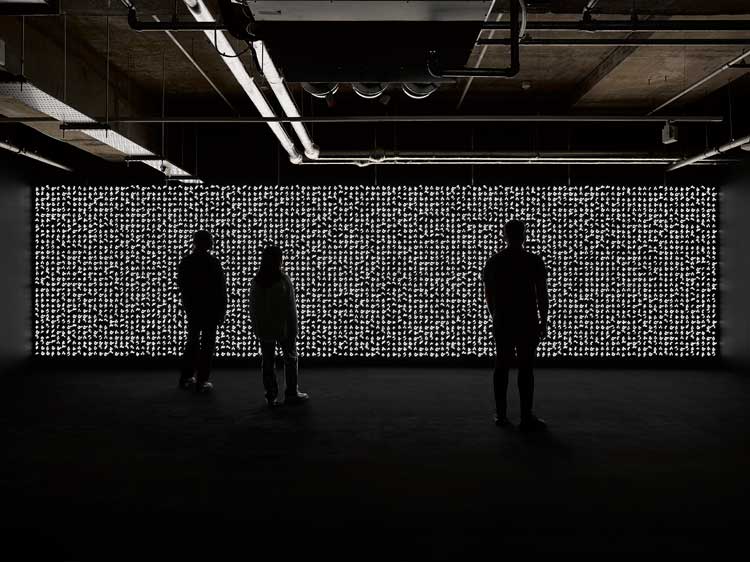

UVA. Ensemble. Installation view, UVA Synchronicity, 180 Studios, London. Commissioned by 180 Studios. Photo: Jack Hems.

Visitors enter through a metal doorway and descend a stark stairway to find a brightly lit exhibition entrance with introductory panels that tell of UVA’s “emphasis” on “collective labour and shared creative agency” that serves “to challenge notions of individual genius or singular authorship”. Indeed, this exhibition brings a post-authorial narrative strongly to the fore through intensifying and shifting patterns of language, expressed in various ways in the human and non-human spectrum. We also encounter evidence of an enduring commitment to the evolution of established collaborations, so that over the course of the exhibition we can begin to recognise the interrelation of one work with another and, most importantly for those who may have seen the works of UVA before, the entangling of new works in a reflexive way with earlier iterations. This is a bold gesture with respect to a 20-year-old survey exhibition.

First off is a magnetic work called Present Shock 2 (2023), iterating a theme of informational overload that has been explored by UVA in various projects made in collaboration with the group Massive Attack and in particular with its founder, the artist, producer and vocalist Robert Del Naja, since 2003. The intensity of the experience for the viewer of this latest manifestation, which fills a wide screen almost the breadth of the room, recalls the effects achieved by the groups working together on a multiscreen display for live performance launched at Manchester Festival in 2013, Adam Curtis Vs Massive Attack, with which Curtis, a leading documentary film-maker and technological visionary, was also involved. The title of the current work grounds the projections of earlier instantiations of these relations into today’s scenario, as one in which we now recognise the incalculable speed of artificial intelligence-based calculations that form and dissolve before our eyes, seeming to be factually based but open to conjecture. In turn, a loss of capacity to discern pattern or meaning within these accelerating data flows underpins a growing sense that what we are encountering is no longer a future projection but, as the title of this work implies, is now the felt stuff of daily existence.

UVA. Our Time. Installation view, UVA Synchronicity, 180 Studios, London. Commissioned by 180 Studios. Photo: Jack Hems.

Following immediately on from this sense of unsettling information blindness due to vertiginous accelerated excess, the next project in the sequence, Our Time (2015), plunges us into what initially seems like a tunnel of darkness. As one gradually finds some kind of bearing (and a wall to lean back on), recognition grows of what is occurring within the environment – a balancing act between the swinging of pendulums at various levels and a metronomic beat that is difficult to predict, appearing at once constant and random. I join others in the space in attempting somehow to breathe with the movement of the swinging objects, absorbing their rhythm and listening deeply for some kind of pattern. Coming after the smash and grab effect of the velocity of LED data in the earlier room, this is a masterly switch towards concentration on time as a contemplative field and on space as somewhere in which one might need to find a refuge. The heart-clenching score for this work was composed by Mira Calix, whose death in 2022 came as a major shock to many with whom she had collaborated on stunning electronic pieces and sound-sculpture. Awareness of this adds somehow to the darkness of the event-space in which this work is located.

I move slowly on to what Clark describes as the centrepiece of the exhibition, again an iteration of an earlier collaborative relation. In 2016, UVA was commissioned by the Fondation Cartier in Paris to work on the Great Animal Orchestra project, initiated by the California-based bio-acoustician Bernie Krause. Earlier this year, the Guardian reflected on the arrival of the project at San Francisco’s Exploratorium. While the article makes only brief reference to UVA, the collaboration has been transformative in making even more impactful on a multisensory level aspects of Krause’s astonishing long-term research into detection of shifting patterns of sound in the natural world that throws new light on environmental change but also on ecological degradation.

UVA, Polyphony. Installation view, UVA Synchronicity, 180 Studios, London. Commissioned by 180 Studios. Photo: Jack Hems.

Fitting with the spirit of open-ended research and adjustment in the light of changing circumstances that seems intrinsic to the development of several of the newer pieces being shown here, Polyphony (2023) builds on the collaborative relationship established with Krause with respect to the future of other species and feeds into this a concern for the human. The work conveys a sense through sound and light interaction of the interdependency and mutual symbiosis between rhythms and sounds produced by tribal peoples living in Central African Republic and creatures, including frogs, insects and birds, living in the surrounding natural environment. Again, Krause’s long-term repository of field recordings provided access to knowledge of this interaction as did the collections of the ethnomusicologist Louis Sarno, to whom UVA were introduced by Krause. Invited to enter a rounded structure and to, in a sense, dwell within this in a mode of close listening, we are no longer audience members but participants in a polyphonic environment that surrounds us. But, as Clark later tells me, what is occurring, in a way that eludes most of us encountering the work, is that, above our heads, we are listening to sounds from the natural environment, while the sounds below our feet are artificially generated and human-engendered. Indeed, I was caught between listening and moving around when taking part in this process. An unsettling gap between the rhythms of what was above and what was below within this audiovisual habitat prompted a sense of subliminal unease. Do we stay or do we go? This, like much in this speculative exhibition, is left open to personal interpretation.

UVA. Edge Of Chaos. Installation view, UVA Synchronicity, 180 Studios, London. Commissioned by 180 Studios. Photo: Jack Hems.

An asynchrony between that which is programmed and rules-based and that which may not be depending on contingency of behaviour finds further added edge in the work titled Edge of Chaos (2023). Clark has spoken about this work as a “new departure” in terms of a progression in the techniques used by UVA in terms of control and random behaviour by objects in the space. Once I registered the presence of a thin wire guarding the space in between me and what I immediately register on hesitant entry into the gallery to be a double pendulum sculpture that appears to be swinging about in ways that are not perceptibly predictable, I felt a little safer in moving about the room to get a clearer sense of the experience. What is happening here is indeed extraordinary, premised on a sense of recognition that the human sensorium might find some visceral pleasure in a spatially constrained, temporally open engagement with the thin line between order and chaos. Clark has also told me that the work for him represents a level of duality, of “something that is chaotic but semi-controlled”. The introductory panel, meanwhile, refers to a “transitional space between order and chaos, pattern and noise” that is “considered the locus of creativity, adaptation and self-organisation in complex systems”. Indeed, there is a sense of marvellous play at work in this instance, where I begin to sense that the double kinetic pendulums that have me transfixed are also watching me and that somehow my most random thoughts might in turn stimulate their random responses. A superb score by Dave Meckin adds admirably to the suspense.

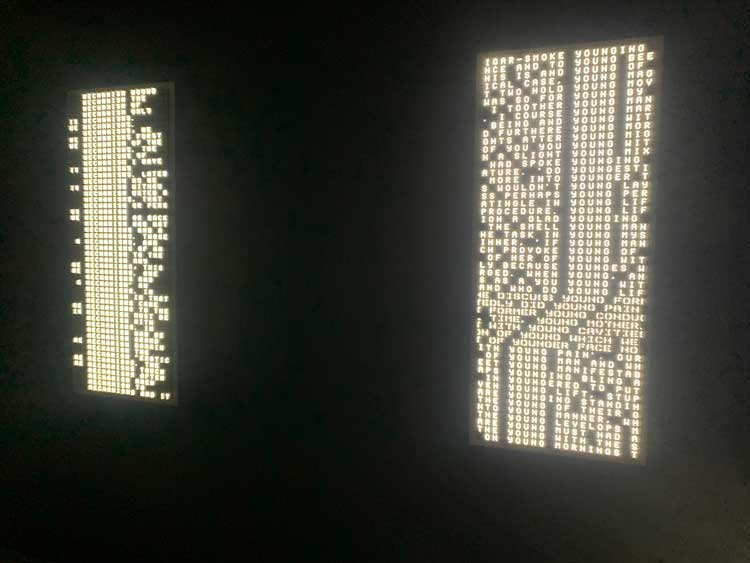

UVA, Etymologies. Installation view, UVA Synchronicity, 180 Studios, London. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

Of the other four works in the exhibition, one – Etymologies (2022) – deals directly (and silently) with the permutation of textual patterns drawn from the writings of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung (the latter of whom generated the term “synchronicity”). UVA has fed lines from both into a large language model and used Markov-based statistical analysis techniques to produce predictive patterns and modes of difference and its iteration. The resulting texts by Jung and Freud, morphed by means of this AI-related intervention, hang in counterpointing parallel, and the simplicity of this display carries strong resonance for me of how late concrete poems and early conceptual artworks began to evolve towards the end of the 1960s.

I see strong influence also of mid-century concrete art and constructivist forerunners, in the work entitled Chromatic (2022). At the same time as I am assimilating this visual reference and watching the geometrical planes move in ways that Max Bill might have conceived but would have been unable to make happen, I swiftly sense an edge of collision rather than synchronicity with the expressive tonality of the musical accompaniment by composer Daniel J Thibaut. On the accompanying panel, “harmonious and discordant results” are, we are told, being consciously induced by a “responsive collaboration between man and machine”. That this responsive collaboration can involve degrees of counterpointing resistance to anti-expressive algorithmic patterns seems to be subtly intimated in various ways within this exhibition, which reflects an ambivalent and disruptive approach to concepts of technological spectacle. This, as ever with UVA, seems timely and reflexively intimating, challenging us to waken from a digitally induced trance and yet showing us at the same time why we might be aesthetically hypnotised. Catch this exhibition if you can.