Philip Hughes. Image courtesy the artist.

by JANET McKENZIE

The London-born artist Philip Hughes (b1936) focuses on the natural environment and human intervention and activity. His new book, Painting the Ancient Land of Australia, with a foreword by the Australian architect Glenn Murcutt, the recipient of many international awards including the Pritzker prize, and an introduction by Jonathan Meyer, can be seen as an extension of his practice, with topographical drawings in the landscape accompanied by descriptive diary entries. Murcutt describes his first visit to Hughes’s London studio: “There, among layers of maps, were the most wonderful documents that defined topography through the beauty of reading contours – in the land, in the form of rock outcrops, in the structure of tree cover. Philip’s work at the time developed with and through topographic maps. That love of geological form continues, and his Australian works show that [his] art is made through a topographer’s eye.”

-1993-.jpg)

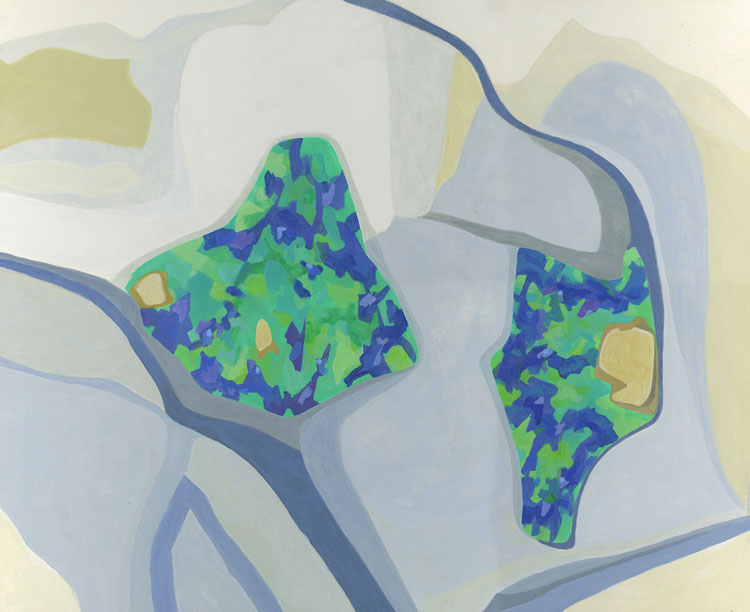

Philip Hughes. Lava Flow (Lord Howe Island), 1993. Acrylic on canvas, 86 x 148 cm. Image courtesy the artist.

The effects of climate change and human impact on the environment are increasingly felt worldwide, especially so in Australia. Australia’s most eminent architect, Murcutt is known for architecture that operates within the continent’s unique climate. In his introduction he says: “The average temperature across the country over the past three decades has risen 1.5°C. Coupled with a severe drought and very early seasonal heat, the conditions during the spring and summer of 2019-20 made for catastrophic, uncontrollable wildfires on a scale never before experienced by Australians … some 5.4 million hectares of land was affected in New South Wales alone, and many fires occurred within the country’s national parks. An estimated one billion native animals perished, together with their habitat. Rainforests burnt for the first time ever, and most are unlikely to recover, as the intense heat of the fires destroyed the seed bank distributed across the forest floor. Then, finally came the heavy rains that extinguished the bushfires – and delivered floods.”

Hughes has crisscrossed the vast continent of Australia since the 1960s. His 1983 Tasmanian works were made in response to protests against the proposed dam on the Franklin and Gordon rivers, 10 years after the flooding of Lake Pedder. Hughes wanted to raise international awareness of environmental issues. His elegant images of the Mount Tom Price mine in Western Australia indicate the sheer scale of destruction sanctioned in the name of economic prosperity. They also present the conflict of interest at the centre of Aboriginal Land Rights, of sacred sites against the powerful mining lobby. Through text and image, Painting the Ancient Land of Australia is a consummate production, weaving details of historic, cultural, geographical and geological material, making a major contribution to contemporary art practice with an urgency for the global environmental crisis. I interviewed the artist on his return to London after spending most of lockdown in Herefordshire, near to the Welsh border.

Philip Hughes. Opal, 2020. Image courtesy the artist.

Janet McKenzie: Painting the Ancient Landscape of Australia is a beautiful production and features work created over five decades. I am glad that you refer to the ancient nature of Australia, because that immediately signifies the ancient yet living culture of the Australian Aborigines and the fact that they are the original inhabitants.

Philip Hughes: I have in mind that there are two concepts of “ancient”. One is the geology that my work addresses. In the Kimberley ranges, for example, the rock forms are ancient. And there is the Aboriginal culture, too.

JMcK: When I first looked at your work, I knew you had studied at Cambridge before becoming a self-taught artist, and I therefore assumed you had read geology. But you studied engineering. When did you fall out of love with engineering and how did your career as an artist evolve?

PH: I fell out of love with engineering almost straight away. In fact, what I loved at that stage was mathematics and I was very good at it. I was not good at anything else, so I was persuaded to read engineering, but I never had a feel for it. But I came back to maths and had a major first career in computer software. It was the kind of computer modelling that required mathematics.

JMcK: When did you first travel to Australia?

PH: When I was 17, in 1953. My parents emigrated to Australia when I was 16, but I stayed on in England to complete my schooling. Then I took what is now called a gap year in Australia and returned to go to Cambridge. My parents and sister stayed in Australia for the rest of their lives.

JMcK: There are numerous, significant artists in Australia – historically from the 18th and 19th centuries and, more recently, in the 20th century – who have travelled to Australia and painted and annotated it visually through completely fresh eyes, unlike those who were born and bred there. I am thinking of John Wolseley, Peter Booth and Jörg Schmeisser, all of whom migrated to Australia, and David Blackburn and Antony Gormley, who, like you, travelled several times to Australia, producing marvellous work but always returning to England.

PH: I’m struck by how separated the UK and Australian art worlds have become. There was a time when artists such as Arthur Boyd and Sidney Nolan exhibited regularly in London and there was terrific exchange between the two cultures. They felt they had to travel to England, to London, to be properly received.

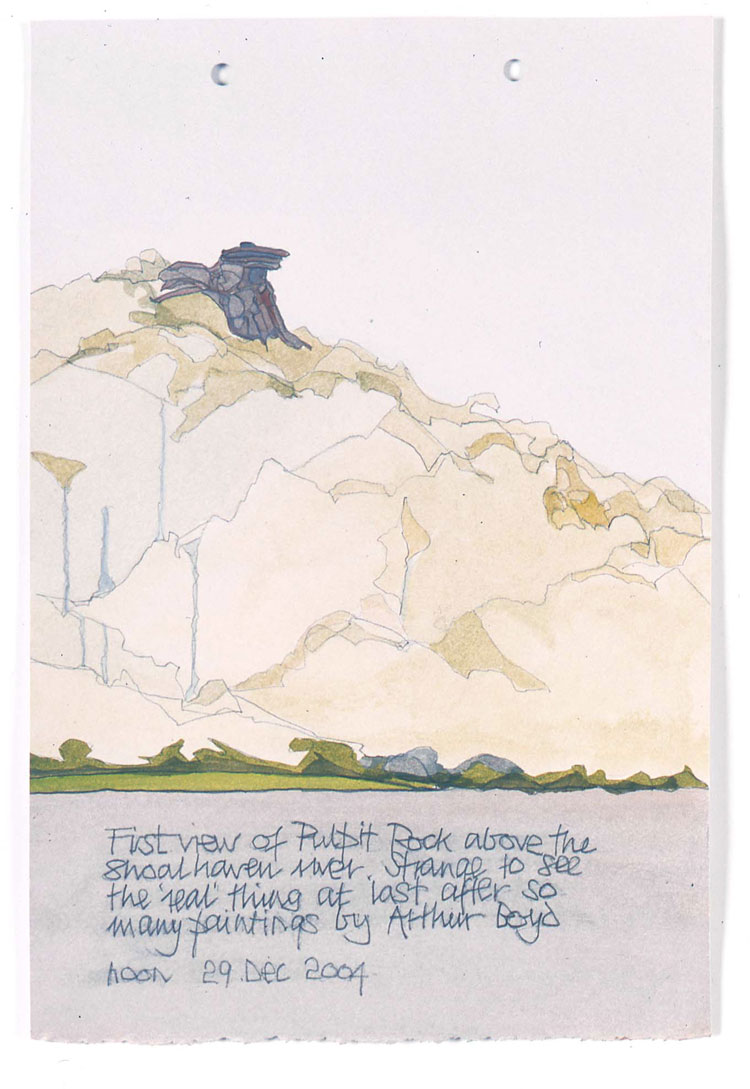

Philip Hughes. First view of Pulpit Rock, Bundanon, 2004. Acrylic and gouache on paper, 60 x 60 cm. Image courtesy the artist.

JMcK: Traditionally, the greatest ambition of Australian artists and art historians was to travel to European museums to see the work in the flesh, and London was viewed as a cultural centre. But Australian society has become less British, more multicultural, and art writers in London are out of touch with those changes. And although Australia at the Royal Academy in 2013 was the largest and most comprehensive exhibition of Australian art in the UK, the critical response was terrible.

PH: I’m a tremendous admirer of Boyd and of Fred Williams, who I think was one of the best landscape artists in the world. I don’t think he’s been adequately appreciated in the UK. Recently, a respected gallery in London showed John Olsen’s drawings and paintings and not a single one sold. The Australia exhibition at the Royal Academy was badly received and reviewed.

JMcK: I am interested also in the fact that your work is described as topographical and that, historically in Australia, topographic art was created in order to describe and understand the strange land of Australia and it was often done by scientists.

PH: I found it extremely difficult at first, as the landscape in Australia is so deeply different. You need to wrestle with the difference. You need to go back to the major European artists of the 19th century to realise that they first painted the land as if they were painting England or a part of Europe. There were many wonderful paintings made, but it is not quite the same thing. I found it was difficult to start. Much of my early artwork was based on the very cultivated landscape of the Sussex Downs, with field patterns, and that was completely irrelevant visually and artistically when I first drew the Australian landscape.

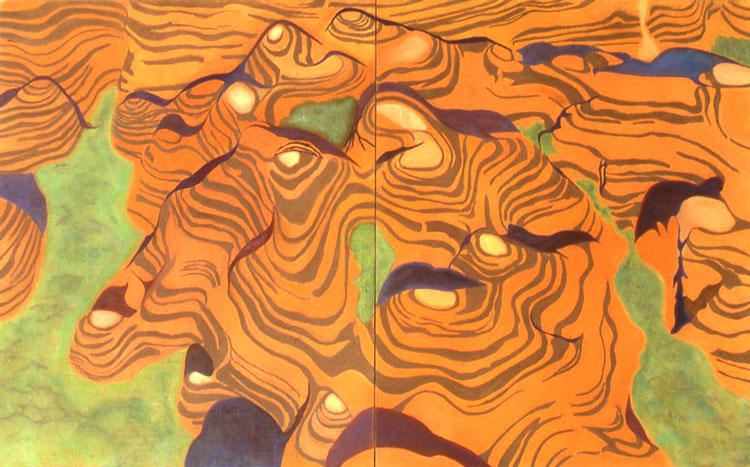

Philip Hughes. Bungle Bungle, 1995. Image courtesy the artist.

JMcK: Could you describe your drawing method, since it clearly underpins your practice?

PH: Absolutely. Drawing underpins my work: specifically drawing in situ. Drawing captures the memory of a place like a diary and these drawings also contain words that describe the place and my visit. I don’t apply paint in situ. The drawing is critical because it is the first and the last point of my methodology. My work is about the simplification of the landscape, reducing it to blocks and lines. The drawings are usually done very quickly; I don’t sit in the landscape for hours, for the view. Most of my drawings can be done in less than 15 minutes. The information I gather goes all the way through to the final work, which is an abstraction of the structure that takes place in the first sketch. I hardly ever work from photographs. I don’t paint in the landscape. My work depends on the simplification of the structure and stays with it as it changes and develops.

JMcK: You are a great walker and, in that process, you discover the landscape and extract a sense of space, both while you travel on foot and while you are drawing. Yet it is not the same methodology or conceptual approach as that of Richard Long?

PH: It is not like Richard Long at all. There are some points of connection and I greatly admire his work. He and I have talked about the way he walks and, for him, the walk is the work of art. Sometimes that is the same for me. Walls Lookout Track (2020) was made after travelling through the Blue Mountains and the walk is the work of art. I am using fragments – the flower becomes an enlarged detail, the same size as my drawing of the track itself. I often draw a path, trying to capture the act of drawing, so in that respect I am working like Long. Returning to Sydney from Lightning Ridge in November 2019, after nine hours of driving, we started to cross the mountains, coming up from Lithgow. We had to take this route to avoid the bushfires occurring in parts of New South Wales that day, including in the Blue Mountains. We stopped and walked on the Walls Lookout track. It was beautiful, swathed in wildflowers, the route itself made of worn, pale yellow sandstone. Just weeks after walking this track, it and the surrounding forest were devastated by fire. The last panel was added showing the burnt-out scene.

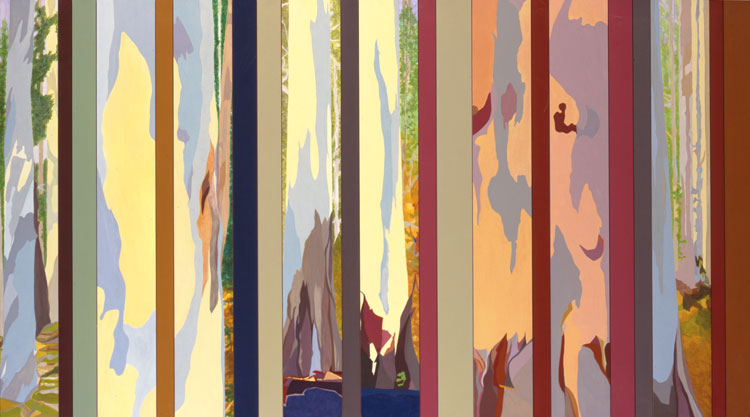

Philip Hughes. In the Blue Gum Forest I, 1995. Acrylic on board, 120 x 220 cm. Image courtesy the artist.

JMcK: In the Blue Gum Forest (1995) is a double-page spread in the new book and it is a beautiful image of repeated vertical stripes.

PH: The stripes are made from separate strips of wood. I start with eight panels on to which I paint detail. The thinner strips are painted a single colour as abstracted components of the landscape.

JMcK: The Bungle Bungle Range, in the Kimberley region of Western Australia, is a gift for artists. Can you describe your first visit to Cathedral Gorge in the Bungle Bungles?

PH: It was fantastic. I’ve been to many places around the world and within Australia and I can tell you that it’s up there with the very best. It’s quite difficult to get to – we flew to Halls Creek and hired a four-wheel vehicle to drive there, then we arranged a helicopter to fly over the formation. It’s great because, unlike Uluru, it’s not a tourist destination with other people around. Most unusually, Bungle Bungle (1995) was done from the air. I can’t draw when I’m flying – so this work was done from a photo I took. It’s important to be able to use aerial views. Aboriginal art is an aerial view. They were the first to realise the powerful images from the air, even though they could not fly.

The magic of the Bungle Bungles comes from the unique grouping of the dome-shaped rocks and from the striped appearance of the geological strata, the result of alternating layers of clay-rich and iron-rich sandstone. The high moisture content of the clay-rich layers supports the growth of cyanobacteria – single-cell organisms that give these bands a grey hue. Sandstone layers that are too dry for the bacteria to survive are coloured red by their coating of iron oxide. What results is a striped effect of grey and red bands on the rockface.

JMcK: You took part in the protests against the proposed dam construction on the Franklin and Gordon rivers in Tasmania in 1983.

PH: It was one of the most significant environmental campaigns in Australia. The local town was hostile to protesters because potential jobs were at stake. I went with the intention of doing drawings at the dam site and then developing paintings, to be exhibited in London, to further international support for the protest. I was taken upstream to camp at the site and provided with facilities to work there. The river is quite extraordinarily beautiful, with a stillness, a calmness as it flows through the virgin forest. All of this would be destroyed if the dam went ahead. Indeed, one of my paintings, Warners Landing, Building the Access Road (1983) shows just the beginning of destruction as the bulldozers started work.

Philip Hughes. Warners Landing, Building the Access Road, 1983. Gouache and acrylic on paper. Image courtesy the artist.

The protest movement was effective in raising awareness. It became an issue of federal v state as Tasmania carried on with construction. The rivers became part of a Unesco World Heritage area, and that gave the federal government the right to intervene. The project was halted. The vast wilderness of south west Tasmania remains almost entirely untouched. I did exhibit the paintings in London in 1984, even though publicity was no longer relevant.

JMcK: Can you tell me about your visit to the Mount Tom Price iron-ore mine in the Pilbara region?

PH: Nothing can prepare you for the sheer scale of the open pit at the Mount Tom Price mine. It is a series of terraces going down and down. They are in fact much deeper, but viewed from the edge of the mine, this is not apparent. I wanted to go to the mine at Mount Tom Price and the surrounding Hamersley Range after seeing a suite of large paintings, in London, by Fred Williams. I was particularly impressed by his representation of the intense deep red of the Pilbara landscape. I approached the owners of the mine, Rio Tinto, and they kindly agreed to my visit and provided accommodation with the miners for my wife and myself.

A railway has been built specifically to take the iron ore from the mine to the port of Dampier, from where it is shipped, mainly to China. Everything about the mine and its operation is on a huge scale, as The Terraces of Tom Price Mine (2005) shows. It was very interesting. The drawings at the mine were more detailed and time-consuming than my usual in situ drawings. I sat on the edge of the crater for ages. It’s only afterwards that one thinks about the ramifications and the fact that Australia is tearing the continent apart. There is an inevitable clash of interests between mining, which is so important to the Australian economy, and conserving the unique landscapes and ecology. Further, there is a cultural clash between the economic imperatives of mining and the preservation of vital Aboriginal sites.

Philip Hughes. Lightning Ridge: Miner’s Hut 2019-20. Acrylic and pastel on paper. Image courtesy the artist.

JMcK: The Lightning Ridge paintings and drawings (2019) indicate your working method clearly, including your diaristic notes.

PH: Lightning Ridge is the world capital of black opals. Though they are called black, they are in fact a myriad of dark colours: blues, greens and reds. In November 2019, I drove with my son-in-law, Jonathan Myers, and granddaughter, Ursula, from Sydney to Lightning Ridge, an 11-hour drive north-east inland and towards the Queensland border. The effects of the long drought were terrible.

Unlike most mining ventures around Australia, such as Tom Price, and the world in general, Lightning Ridge mining is by individuals on tiny plots. There are dozens of mines, perhaps hundreds. The miners, who come from all over the world, often live beside the mines. The mines are unseen, situated below ground – the only traces of white kaolinite-rich claystone that punctuate the landscape. Among these are old-looking machines and abandoned trucks, some rusting away. It is surreal. I have tried to capture this strange land.

JMcK: We share a love of Bundanon, on the south coast of New South Wales, the property that Arthur Boyd gifted to the people of Australia, after painting hundreds of visionary works of art there that capture the quintessential spirit of the Australian landscape. Murcutt has designed studios there for an artist-in-residence programme.

PH: My trip to the Pilbara region in Western Australia paid homage to Williams; the trip to Bundanon was to honour Boyd. I had a friend who had been to the writer’s cottage so I enquired and was offered the same cottage because I could not stay for the normal artist residency, which was longer. I wanted to see the context for Boyd.

JMcK: Have any particular Aboriginal artists had an influence on your work?

PH: No, but I have been to places to view Aboriginal art, particularly the cave paintings in Kakadu that are up to 20,000 years old. And I have been tremendously impressed by Aboriginal artworks in the Art Gallery of New South Wales and in the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, pure abstract works.

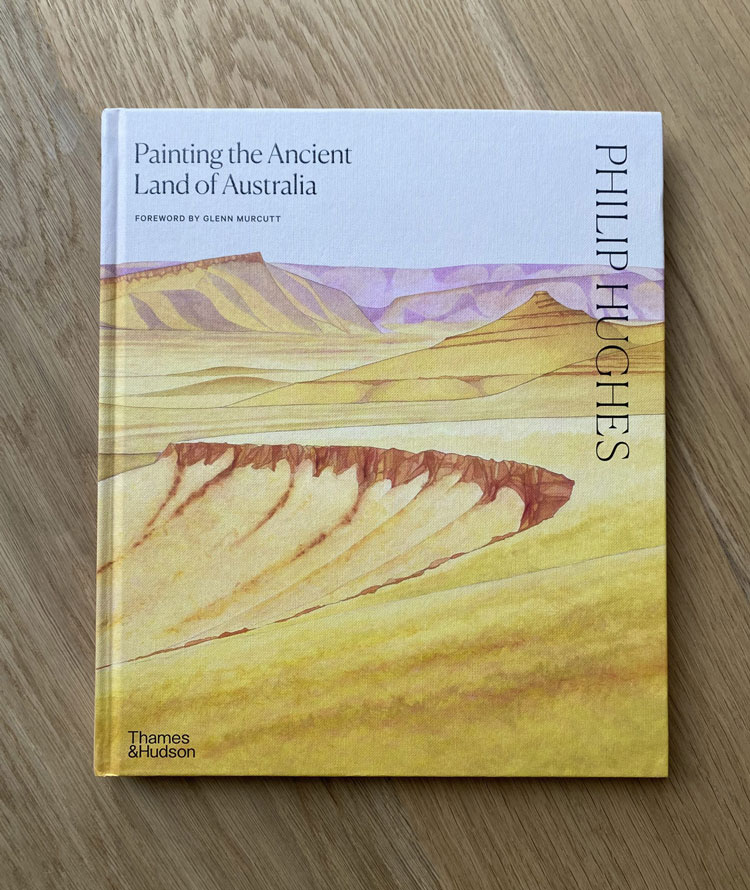

• Painting the Ancient Land of Australia by Philip Hughes, with a foreword by Glenn Murcutt and an introduction by Jonathan Myers, is published by Thames & Hudson (Australia), price $80 and Thames & Hudson (UK), price £40.

Painting the Ancient Land of Australia by Philip Hughes, with a foreword by Glenn Murcutt and an introduction by Jonathan Myers, is published by Thames & Hudson (Australia).