Installation view of Art Now: Joanna Piotrowska: All Our False Devices at Tate Britain. Photo: Tate Photography (Matt Greenwood).

Tate Britain, London

8 March – 9 June 2019

by IZABELLA SCOTT

When I was 10 years old, I used to like hiding in soft, dark spaces. Around that time, I had a precious red camera, used only for special occasions, such as a visit to the zoo. What would it be like, I began to wonder, to photograph something hidden from view. One day, I took the camera under my bed and flash, flash, flash, I spent the whole film.

Joanna Piotrowska’s photographs of intimate, airless interiors expose the latent erotics of the home. Her black-and-white photographs look like awkward family snapshots, but something is off. The family dynamics that she photographs are, in fact, staged, and made uncomfortable by the rub between privacy and display. In her 2014 series Frowst – a word that describes hot, fusty, stale interiors – she arranged family members in queasy, claustrophobic poses: adult brothers in underpants, lying side by side on a living room floor; a mother, squinting at her daughter, hands locked around her neck. These choreographed movements are derived from a book by the German psychotherapist Bert Hellinger, who developed a therapeutic healing method known as Family Constellations. The positions Hellinger devised were aimed at correcting family patterns, but Piotrowska’s photographs draw out oddness, perversion and power. In them, there is a palpable sense that somebody off-camera is directing the scenes, and the soft eroticism is a reminder that role play is a practice of both the classroom and the bedroom, education and kink.

Joanna Piotrowska. Untitled, 2015. Originally commissioned through the Jerwood and Photoworks Awards 2015. Courtesy Southard Reid.

Piotrowska’s current solo show All Our False Devices, at Tate Britain, mixes together photographs from a number of series – all untitled – some derived from her interest in Hellinger, others from the writings of the American psychologist and feminist Carol Gilligan. Gilligan has sought to understand the mechanisms by which teenage girls fall victim to social pressures: how they are socialised, and ultimately silenced. Responding to Gilligan’s research, Piotrowska photographed adolescents at home, in positions of submission. In one, a girl kneels on a staircase, her sailor-striped dress contrasting with a decadent Persian runner, while her face is hidden from view. In another, two young girls lie on a bench, their limbs entangled, as one’s hands covers the other’s eyes.

Joanna Piotrowska. Untitled, 2017. Courtesy Dawid Radziszewski.

The silver gelatin prints are displayed in ice-cream coloured frames – pale blue, raspberry and mint green. Given the content, these nursery colours exacerbate a sense of false innocence – from the viewer’s side – and demonstrate the inherent voyeurism of photography. Projected alongside these images are three 16mm films, showing teenage girls following sets of instructions. The films are imbued with the same uneasy eroticism of the photographs, but taken a step further. In one, three girls touch parts of their body with the tip of their finger – temple, forehead, eye, lips, cheek, earlobe, chin and then lower: collar, breastbone, hip. In the second, a girl performs a sequence of moves, seeming to grip an invisible body, or making ready to throw a punch. Is this witchcraft or yoga? I later discover that these are poses drawn from self-defence manuals; if Piotrowska wants to show these girls taking back control, so to speak, their powers are rendered uncertain. Filmed against a black backdrop, their bodies pop out provocatively, sexualised even when “resisting”.

Joanna Piotrowska. Untitled, 2014. Courtesy Southard Reid and Dawid Radziszewski.

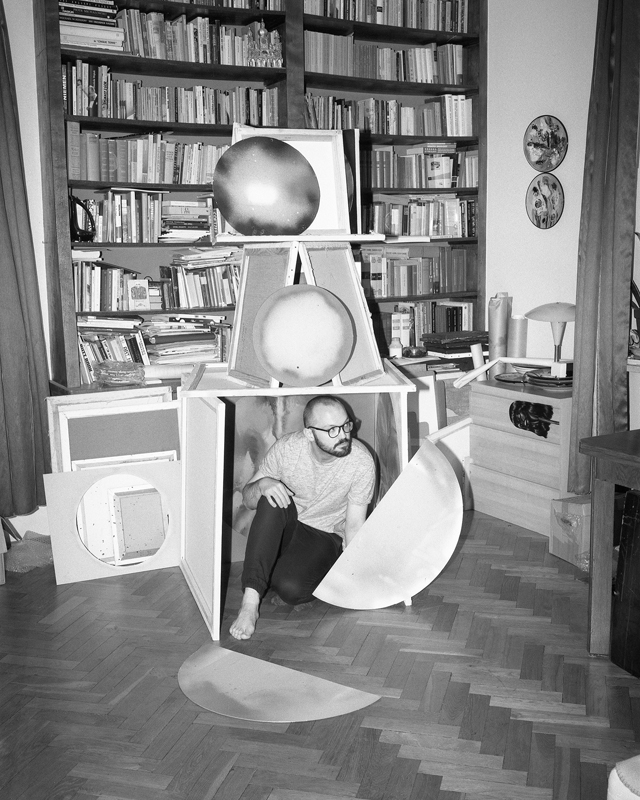

Interlaced between the frowsty snapshots is another series of images, in which Piotrowska asked adults to build hideouts from objects around their homes. They range from high camp to childish – one is made from a big, shaggy umbrella and a pile of cushions; another is more folksy, a pointed tent adorned with mistletoe. The photographs are most strange when the camps are inhabited. In one, a man peers out from a makeshift dwelling comprising rugs, an ironing board and cushions. He has an aura of fake babyhood, his eyes vacuous as he stares idly to the side. In another, a man has deconstructed a desk and built a play den from the segments of plywood. He sits on the hard parquet flooring, barefoot: behind him, the gilded leather spines of volumes on a bookshelf glint. If men in temporary shelters look like giant babies, women appear vulnerable. Further along the wall, a woman lies in a corridor, in a camp made of pots and pans, a lamp, a cafetière and bedsheets. There is no comedy here. Instead, she looks as if she has been thrown out of her home; as if these are the only things she has in the world. I am reminded of the philosopher Diedrich Diederichsen’s sense of the codes of looking, and what the viewer brings into the room. “You can only enjoy the peinture of a still life when the food it depicts does not make you hungry,” he writes. Clearly, I am sensitised to women’s pain, what is hidden. Clearly, I am hungry.