Elaine Shemilt. Image courtesy and copyright the artist.

by JANET McKENZIE

A pioneer of early feminist video and multimedia installation and a printmaker and researcher of international repute, the British artist Elaine Shemilt (b1954) addresses the impact of war, conflict, censorship and constraint on psychologies and environments in her work. Coming of age as an artist in London in the 1970s, she created artwork that was progressive and experimental when dramatic developments in technology were taking place. The advent of the personal video camera enabled the ephemeral nature of performance to be captured without a film crew or extensive equipment. Video enabled a nascent aesthetic to find form.

‘I am certain that physiological processes, sensations and desires all leave their traces like imprints on people’

Second-wave feminism fuelled Shemilt’s powerful oeuvre, garnering forces that sought to challenge historic male hegemony and to invalidate its legitimacy in cultural terms and in the art market. The art historical objectification of female identity and the body is frequently challenged in her use of self-portrait. With other feminist artists in the 70s, Shemilt sought to regain control of the representation of the intimate self, without mediation; hence the use of her own body, performed, filmed, projected to the world without a team, an image of self that rejects the stereotypical dichotomous images of woman as saint or sinner, and within the art historical context of male artist and/ female subject. Her voice is thus asserted with visionary candour.

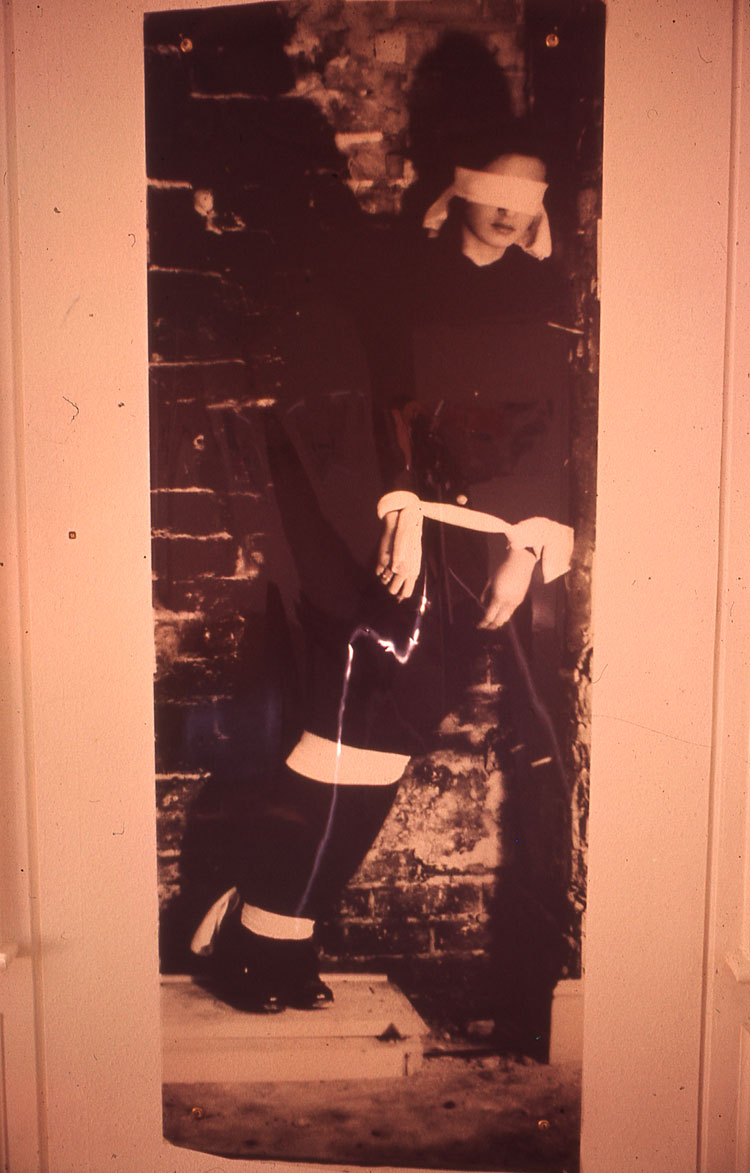

Elaine Shemilt, Constraint,1979. Photo etching, 52 x40 cm. Image courtesy and copyright the artist.

Ancient Death Ritual (1979) Shemilt’s arresting installation at the Hayward Gallery in 1979, links subjective experience to the universality of human phenomena. Works such as the performance and photo installations Constraint (1976;1978) are at once harrowing and courageous. Feminism exposed hitherto private experience with a candid exploration: an exposé of motherhood, the interrogation of gender conflict and sexuality. Using her own body was also pragmatic, enabling her to explore intensely personal phenomena where the use of another person – collaborator or actor – might have been exploitative or reduced the work’s fluid immediacy. Often uncomfortable or extreme (compare Marina Abramović or Mike Parr) there is an authenticity in the artist as subject.

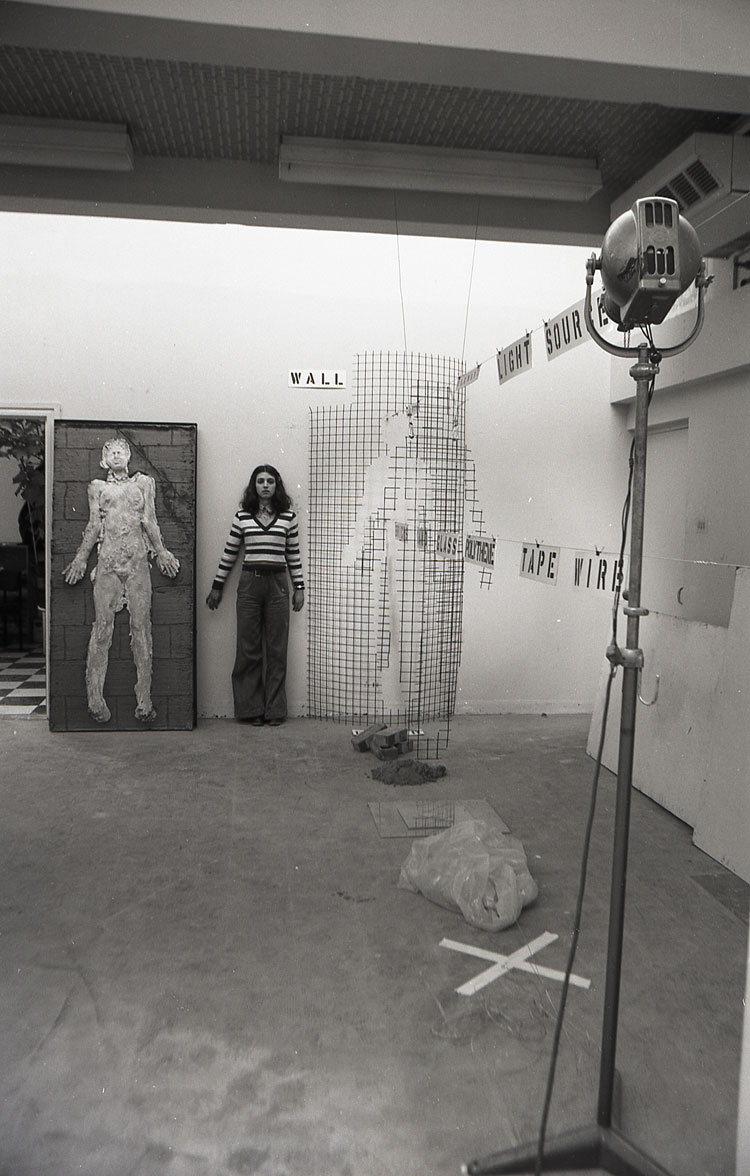

Elaine Shemilt, Conflict, 1974. Installation with performance and video produced in 1974, exhibited at The Video Show, Serpentine Gallery, London, 1975. Image courtesy and copyright the artist.

One of the most thought -provoking video works from the late 70s is Doppelgänger (1979-81), made during a two-year artist’s residency at South Hill Park Art Centre in Berkshire. It has been recovered and digitised by Rewind Artists’ Video and forms part of the Rewind Collection. Three other works were exhibited at the Video Show at the Serpentine Gallery in May 1975: Conflict; Emotive Progression; and Iamdead. Since its recovery, Doppelgänger has been widely exhibited as an installation work in Dundee, Milan, Rome and Shanghai.

Elaine Shemilt, Iamdead, 1974. Photo documentation of the video performance. Monochrome videotape 1/2 inch EIAJ format. Image courtesy and copyright the artist.

An investigative irony is employed in Women Soldiers (1982) to explore the role of women in the military forces that expands to form a more general critique of the role and status of women and how they are represented by media and society. A script pillaged by Shemilt from a military recruitment campaign is read as a voiceover by her friend, the artist June Raby, that describes the “requirements” for an unspecified job in the army. The juxtaposition of sound recordings of the bombing of Beirut in 1981 with photographs taken by Shemilt at a British army training camp, military paraphernalia, naked images of herself from performances and beauty product advertisements create a powerful antiwar statement. Women Soldiers was recovered by Rewind in 2017.

Elaine Shemilt, Women Soldiers, 1982. Screen print, 190 x 50 cm. Image courtesy and copyright the artist.

The personal as political message is central in Shemilt’s impressive career, her most poignant and raw early work informed by her experience of growing up in Northern Ireland between the ages of six and 18 during the Troubles, where the impact of civil war formed a painful backdrop to her childhood and coming of age.

In the 90s, Shemilt’s work was provoked by, rather than being “about”, the civil war raging in the former Yugoslavia. The Bosnian war claimed the lives of an estimated 100,000 people and displaced more than two million. East West was part of a series of works included in Behind Appearance, a solo touring exhibition to the US that comprised 20 etchings, screen prints and lithographs, and culminating in an expanded iteration in Dundee in 1997.

Elaine Shemilt, Tension, 1995. Screen print on latex,198 x 2013 x 274. Installation at Cooper Gallery, Dundee. Image courtesy and copyright the artist.

The exhibition included photographic documentation of several installations (screenprints on latex with metal and rope) which exploited the use of multiple and unfixed viewpoints. The searing images of man – using large-scale printmaking techniques – attempted to assert a continuation of installation within the artist’s practice. The images were thus amplified, resulting in poignant works that addressed the unconscionable state of humanity. The drama evoked in exquisitely rendered flayed bodies in Hollow Men (1996) or Mind Full of Dreams (1996) refers to the multifarious levels of reference: psychological, political and subjective.

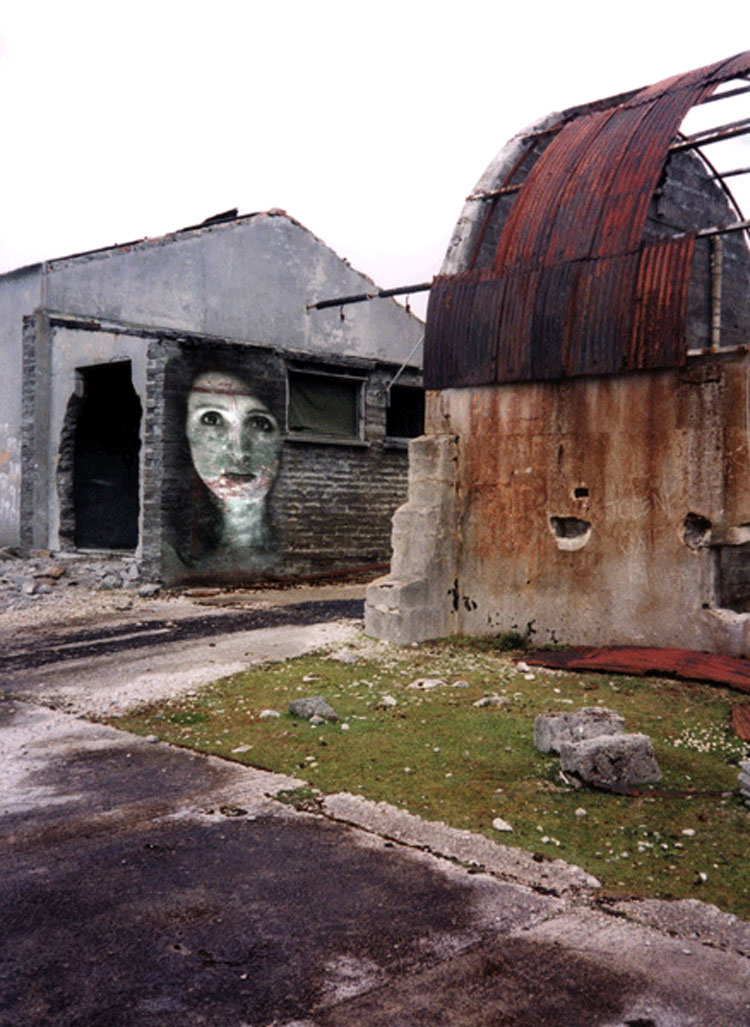

Elaine Shemilt, Traces, (Ajax Bay Series), 2002. Iris Print, 114 x 90 cm. Image courtesy and copyright the artist.

A cold and haunting fear exists simultaneously with sublime beauty years later in works such as Traces (2002) created for the research project and exhibition Traces of Conflict: The Falklands Revisited (1982-2002) at the Imperial War Museum, London. Shemilt’s work addresses dichotomies and paradoxes; subjective as opposed to universal experience, nakedness versus the nude, the particular in relation to the mythical.

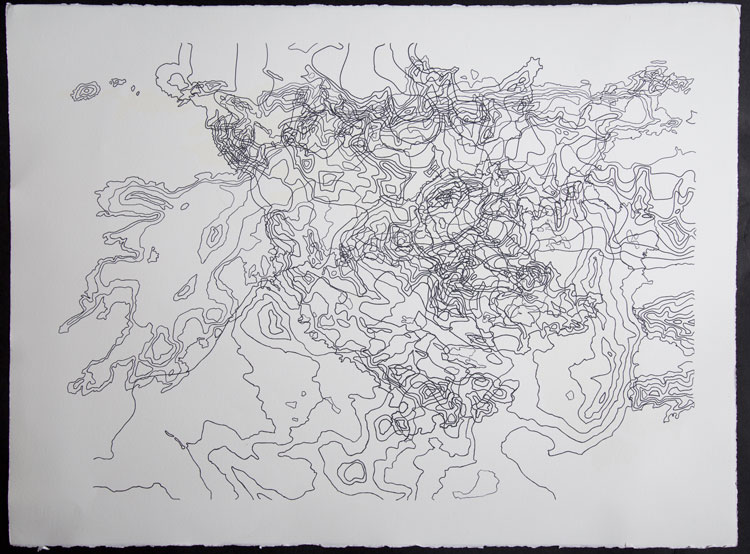

Antarctic Journeys: Mapping: South Georgia and the Dry Valleys of Antarctica (2009-2011) is a multimedia international collaborative project with scientists in Edinburgh and at the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton, whose research focuses on terrestrial ecology and soils in polar regions. As a founder member of the Centre for Remote Environments and The South Georgia Heritage Trust, Shemilt’s role was to augment the scientific research through visualisation. These are forbidden locations to most people and difficult to visit. She created haunting, ethereal forms – maps that provide the viewer with a holistic emotional experience while retaining their physical accuracy.

Elaine Shemilt, Mapping South Georgia, 2011. Etching, 86.5 × 65 cm. Image courtesy and copyright the artist.

Shemilt studied sculpture at Winchester School of Art and printmaking at the Royal College of Art. She has exhibited internationally, including at the Hayward Gallery, the Imperial War Museum, the ICA London, the Edinburgh International Festival, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Rome, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and at the Casa di Carlo Goldoni Museum in Venice. Since 2018 her work has been touring within the exhibition Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s, from the Sammlung Verbund Collection, Vienna, to Stavanger Art Museum, Norway; Dům umění města Brna, Brno, Czech Republic; Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona, Spain, and the International Center of Photography, New York City. She was principal investigator on the Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded project EWVA – European Women’s Video Art in the 70s and 80s (2014-19), a major contribution to the hitherto marginalised field. The research project culminated in a scholarly publication that enables us now to understand the vital role of video art within the women’s movement. An examination of Shemilt’s inspiring oeuvre enables us to reappraise this seminal period, to understand where we have come from and the roles we have assumed.

Studio International visited Shemilt’s studio in Broughty Ferry, Dundee.

Janet McKenzie: Can you describe the impact on you as a child of growing up in the Troubles in Belfast?

Elaine Shemilt: Even as a teenager it seemed to me that The Troubles in Northern Ireland was a euphemism for what felt like civil war. Mass murder and random killings made me question the value of life. What belief system could possibly invoke a desire to wipe out the lives of people with such ease? At any moment, I could have been killed by a bomb as I travelled home from school. On more than one occasion I was nearly killed. The experience left me wondering what the point was of my continuing to exist when others didn’t. I asked myself these questions consciously and subconsciously over many ensuing years.

JMcK: What first took you to the Falklands? Can you describe the complex response you had to the Falklands War, given that your mother was Argentinian?

ES: Put simply, my father was English and my mother was Argentinian. Having come out of Belfast, I hated the jingoistic attitude that people displayed at the outbreak of this war. However, it was not until I went to the Falkland Islands (the Malvinas) 20 years later and began working on an extensive commission with the British military that I felt the harrowing impact of that particular conflict. Twenty years later there were still belongings abandoned in the mountains – plimsolls, old tubes of toothpaste, bullets and war detritus. The young men who suffered and died in 1982 were about the same age as my two sons. The young soldiers must have wondered what on earth they were fighting for. And why? Was the death worth it? The saddest remnants were the letters home to their mothers. Later I discovered graffiti – drawings and poems – on the walls of the old field hospital in Ajax Bay. We arranged to have these cut out of the building, which was close to collapse, and helicoptered across the island to the British military base on Mount Pleasant. We sited them in the accommodation corridor so that contemporary military people could understand some of the emotions expressed by their predecessors.

JMcK: The advent of video was liberating for progressive artists in the 70s. Can you describe what it was like as a young artist having a new and neutral technology/ methodology?

ES: Imagine a world without the instant communication and mutual dialogue that internet and social media enable today. In the 70s, video offered the possibility of addressing new scales and contexts at a time when artists were recognising social change and were also trying to break down barriers within the traditional disciplines of sculpture and painting.

JMcK: What were the immediate benefits of using video to combine performance art with a type of documentary film-making of other aspects of your practice?

ES: It is difficult now to truly remember the dynamic relationship that emerged briefly between contemporary art and the new medium of video in the 70s. When the first Sony Video Portapak became widely available it contributed to a range of activity in the arts linked with social change. For me, it offered an opportunity to create moving sculpture. The simple process of recording allowed for an immediate and effective means of artistic communication. It was fast and relatively cheap. I proposed that my body could be perceived as an object and from that starting point attempt to reflect a political and social struggle that was born out of personal experience. In terms of the medium, the result was a satisfyingly low-tech version of television which could be made in privacy in the confines of my studio without the need for a film crew.

Elaine Shemilt, Doppelgänger, 1979-81. Monochrome videotape 1/2 inch EIAJ format, 9 min 12 sec. Photo courtesy and copyright the artist.

JMcK: One of your most important and intriguing pieces is Doppelgänger. It has attracted significant theoretical attention. The Doppelgänger in literature is used to explore dual personalities. Your Doppelgänger (1979-81) is one of your most poignant explorations of self. Can you explain what prompted it and video in the late 70s?

ES: It is about the outsider – but the outsider who is bewildered and upset about facing life as an outsider. Of course, the reality is that life is about confronting our individuality.

JMcK: How informed and aware were you as a student of French theorists, about the discussion around the neutrality of cinema, the critique of ideology?

ES: I was not at all well informed. At the time, I was reading the work of a variety of philosophers and existentialists, Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre in particular. I was also interested in Simone de Beauvoir’s novels.

JMcK: Why did you not keep your video work?

ES: I didn’t think the videos would ever become a thing of value. I often recorded over a video tape to make a new recording. I did keep all the photographs, drawings and prints that went with each of the videos and I made large prints, etchings and lithographs as a sort of record of the event, but at the time I wanted to get away from the sort of imposing heavy sculptures or permanence of an oil painting. It seemed to me that the value was in the idea as well as the craft of making something that could fill a gallery space and yet be collapsed after a few weeks and the elements recycled into a new artwork. Making art for the art market was of no interest to me. I was naive. but it was perhaps not such a terrible thing. It allowed me to make a lot of work, although I missed my opportunity to sell it.

Elaine Shemilt, Doppelgänger Redux, 2016. Video documentation of re-enactment of original video performance at Nunnery Gallery, Bow Arts – London. Video: Adam Lockhart.

JMcK: Doppelgänger was remade in 2016, performed in London. What prompted the remake of this, your seminal work? What did you learn from re-enacting the performance?

ES: Although it was very uncomfortable to do this re-enactment, I felt it was important to revisit this work as an elderly female artist. Having lived my life, raised children and come to terms with this complex issue of trying to “fit in”, I did the re-enactment and as a result I became a sort of voyager alongside my younger self.

JMcK: In the 90s, the exquisitely rendered bodies and heads in Hollow Men and Mind Full of Dreams (both 1996) were created from sources at the College of Surgeons in Edinburgh. Can you describe your methodology?

ES: I was permitted access to some early drawings done by surgeons before the era of photography. Small and exquisite engravings, which are meticulous anatomical studies, mostly anonymous, as I recall. I had an idea to make an illustration in three dimensions of the poem Strange Fruit by Abel Meeropol. The text, and later a song, were from a poem, written by Meeropol in 1939: the song was popularised by Billie Holiday. It became a protest song about lynching and was written in response to the lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith in 1930. I worked on this idea and created an installation with the artist Arthur Watson. At the time, the former Yugoslavia was at war. We had the plan to photograph and enlarge these tiny illustrations to enormous proportions and to print them on to sheets of latex (with texture and colour reminiscent of skin) and to hang them from a massive structure made from scaffolding and oversized ladders. The exhibition was shown during the Edinburgh Festival in one of Richard Demarco’s galleries. Later, I went on to combine some of the images into a series of works called Behind Appearance.

JMcK: The Traces of Conflict works such as Traces (2002) combining photography and performance within sites of abandoned architecture on the Falkland Islands are possibly my favourite of your works. The inclusion of self (nude performance photos and projected self-portraits) printed as photo-etchings seemingly implies the identification of the artist with the absent lives, leading the viewer to partake in this a memorialisation of loss.

ES: Yes. I feel thatlived experiences accumulate in the walls of buildings. I am certain that physiological processes, sensations and desires all leave their traces like imprints on people.

JMcK: Since about 2010, you have been committed to promote the environmental protection and habitat restoration of the natural wilderness in the Southern Atlantic. Can you explain how your feminist work has evolved into a protest to save the planet?

ES: I wouldn’t claim that my work has evolved into a protest, but I have certainly changed from that introspective and possibly self-indulgent younger artist into someone who looks outwards and around to see what I can do to raise awareness of the need to protect our planet. I see it as a rather more mature form of feminism.

JMcK: Can you describe the wide range of media and methodology employed for your Antarctic Journeys: Mapping: South Georgia and the Dry Valleys of Antarctica?

ES: Most of this work was done through employing a wide range of printmaking techniques. I have always layered and combined techniques. I invent processes where possible, and I experiment to achieve marks and surface effects that could not be made directly – in other words, the printmaking indirect process is integral to the final image. I also made some videos using layers of images created through painting, drawing and printmaking.

Elaine Shemilt, Whale Song, 2024. Oil on canvas, 242 x 121 cm. Image courtesy and copyright the artist.

JMcK: Whale Song (2024) was inspired by your visits to the Antarctic Island of South Georgia and quite a departure from your prints and photographic inspired work.

ES: It may seem to be a departure – perhaps it is? I feel, however, that it is a natural extension of my work as a female artist. My research includes working with the South Georgia Heritage Trust to support scientists who are trying to help the recovery of large baleen whales in our oceans as well as many other endangered species.