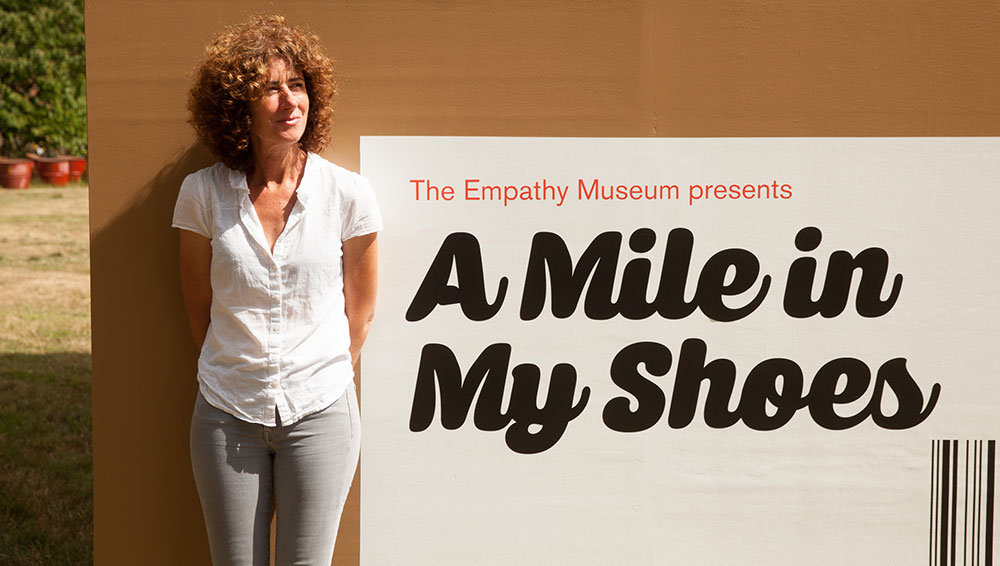

Clare Patey. Photo: James Clarke.

by VERONICA SIMPSON

You could say that the artist Clare Patey (b1965, London) was ahead of her time; she has certainly been a trailblazer for truly participatory, socially and politically engaged performance-based works. Situated firmly in the public realm, her playful, irreverent and trenchant performances and events have been winning over a much broader public than the usual rarefied audience of gallery-goers, while raising consciousness around climate change, plastic waste, fast fashion and food miles, from as early as 1996.

That was the year she commissioned a traffic jam of customised cars and video works by artists including Christo and Jeanne-Claude and Werner Herzog (Art Bypass, 1996), and parked them on the site of the UK’s highly controversial road-construction project, the Newbury bypass, which had been temporarily halted by a large community of vociferous activists who had set up camp in the trees. A year later, she staged Melt!, a mass ice-carving event to draw attention to climate change (with fruits, seeds and flowers frozen into ice sculptures), outside the UN building in New York, for Earth Summit II. At the end of that year, at the Kyoto Summit, she organised pop-up works including a shop that sold nothing (called No Shop, its strapline was “Nothing Could be Better”). All of this was while working for Friends of the Earth.

.jpg)

Clare Patey. The Museum Of; Cheesy records, 1998. Photographer unknown.

In 1998, she opened The Museum Of in a derelict warehouse on the South Bank of the River Thames. Here, over the following four years, she staged many events, but also five participatory explorations of what a museum could be (topics included: personal collections, secrets, dreams and emotions). Giles Waterfield of the Art Newspaper described Museum Of as “remarkable for its humorous, non-judgmental questioning of preconceptions of the nature of museums”, calling it “one of the most remarkable things the South Bank has to offer”.

Clare Patey. Feast on the Bridge ran from 2007 to 2011 as part of The Mayor’s Thames Festival, London. For one Saturday each September Southwark Bridge was closed to traffic for an urban harvest meal enjoyed by over 35,000 people. Photo: Tim Mitchell.

Around that time, Patey’s focus expanded to food – the sustainability of its creation, distribution and consumption, and the connections it forges between communities, and she still runs events under her Edible Utopia banner. Each year from 2007-11, she organised the Feast on the Bridge for the Thames Festival in London. She also co-curated the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Festival in Battersea Park and Feast on the Street in Arizona, as well as helping to launch the Big Lunch (an annual, neighbourhood street party), masterminded by Tim Smits, founder of the Eden Project, in 2009.

Operating outside the commercial art market, she has been the go-to artist and producer for works that combine joyful, creative immersion with important social and political themes. One of her continuing platforms is the Empathy Museum, a project inspired by Barack Obama’s 2013 speech about the “empathy deficit” in American life being just as pressing a problem as the federal deficit. She was approached by the philosopher Roman Krznaric, author of the book Empathy: Why it Matters, and How to Get it, with the idea of creating pop-up museum experiences where people enhance their empathic skills. It was Patey’s notion that each museum experience could be framed within a typical “high street” shopping experience.

.jpg)

Clare Patey. A Mile in My Shoes, Vauxhall, London, 2016. Photo: Kate Raworth.

This is how she came to devise her most popular and enduring work: A Mile in My Shoes. Commissioned in 2016 for the London International Festival of Theatre (Lift), it comprises a simple shipping container, the interior of which has been transformed into a shoe shop, where visitors have their feet measured and are given the shoes of someone whose story links them with that site; in this case the River Thames. They are then asked to take a 20-minute walk around the area while listening to that person’s story on headphones.

.jpg)

Clare Patey. A Mile in My Shoes, Vauxhall, London. Photo: Kate Raworth.

The work has now travelled all over the globe, to Perth, Sydney and Melbourne in Australia, Beirut, Lisbon and São Paulo, as well as Denver and elsewhere in the US, with stories (and shoes) customised accordingly. It is lined up to take part over the summer of 2021, in an event commemorating the 40th anniversary of the Brixton riots, for which Patey is working with the activist group 81 Acts of Exuberant Defiance, and hopes to collect a broad range of personal interviews with people who observed, or were affected by, the riots.

Clare Patey. A Mile in My Shoes, Sao Paulo. Photo: Filip Porto.

Last year, she was funded by Arts Council England, NHS England and the Health Foundation to create From Where I’m Standing, a work that celebrates the unsung heroes of the unprecedented health crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic. It is a physical and digital record of people – from NHS workers to community-garden managers – who have made a genuine difference to people’s lives. Its delivery, while observing lockdown restrictions, was hugely complex, juggling a team of sound artists, interviewers, photographers and their 34 subjects. In its final presentation, people’s portraits appear on estate agent-style boards on a simple residential street, along with a QR code that allows you to hear their story. There is also a website offering the full library of stories and images. In June, that work will travel to Peckham, in south London.

Clare Patey. From Where I'm Standing, 2020.

Yet Patey nearly didn’t pursue art. In 1989, she graduated from East Anglia University with a degree in philosophy. She then spent two-years volunteering in Africa before returning to London and volunteering for Friends of the Earth for six months, thinking she would like to work in international development. However, when a full-time role came up, the colleague managing the interview said they would love to offer her the job, but suggested she go off to art school first, as she was “always banging on about it”. She applied to Central Saint Martins, completing a BA in critical fine art practice in 1995. She then landed a job in her dream arena – making campaigning public artwork – through a jobshare project set up by the University of Brighton’s newly established (though now defunct) Centre for Life Arts Research, in tandem with Friends of the Earth. Art Bypass was her first project for them.

She talked with Studio International - with interviewer and interviewee (socially distanced) at opposite ends of her orange VW campervan – as lockdown ended in London.

Veronica Simpson: The first gig you landed, straight out of art school, was one of the most extraordinary gigs of your career. Can you tell me how your Art Bypass project evolved?

Clare Patey: It was the time of the Newbury bypass and there were lots of protests about the road going through ancient woodlands and destroying it. I had the idea of building a mile of motorway in the middle of the countryside overlooking where they were building all the roads. I wanted to give 20 artists an old car, and ask them to make a work about car culture and our relationship with the car. We created this space that had roundabouts with performances on them, and giant projections. Then it just grew. There were loads of young artists who were really keen to be part of it and camping in trees, and so we involved the road protestors, we involved local community groups. We involved lots of different artists.

.jpg)

Clare Patey. Art Bypass; A Good Little Runner by Paul Williams, 1996. Photographer unknown.

VS: That sounds like a tough act to follow. What came next?

CP: Friends of the Earth did loads of stuff at the Conference of the Parties, COP2, in 1996. There had been a big event, the Earth Summit, in Rio in 1992 and the follow up was in 1997, Earth Summit II, at the United Nations building in New York. We worked with Earl Covington, an American ice-carving champion who made carvings of things like mermaids on top of elephant trunks. He must have thought we were mad. We got into his studio, where we froze natural things, such as fruit and flowers, and made these incredible sculptures in ice. It was called Melt!, and it was a monument to human folly and climate change.

VS: After two or three years of this, you left Friends of the Earth and were invited to set up the Museum of?

CP: Yes, I ended up with this huge building on the South Bank (The Bargehouse), which had been derelict for 40 years. Iain Tuckett, who ran the local community housing and arts co-operative Coin Street, said to me: “If you can come up with a good idea for the building, we’ll fund it.”

I wanted to make a space that was about questioning the cultural space of the museum, to make the whole thing about participation, because they wanted to turn the building into a museum eventually, about the River Thames. My whole Museum Of intervention was going to inform the decisions that were made about what happened in that building.

VS: So it was a prototype “meanwhile use” project?

CP: Yes, but it was designed so that the programme and outcomes would feed directly into the future use.

.jpg)

Clare Patey. The Museum Of; Kinder Toys, 1998. Photographer unknown.

The first one was the Museum of Collectors, which featured everything from Kinder egg toys to cheesy record covers. The second was the Museum of Me. National museums tell this story of national identity, but who is it really about and who is it for? We asked people: “How would you tell the story of your own identity? What would you put into it, what would you leave out it, what would your decision-making processes be?” The strapline was: “The Museum of Me: You Belong in an Exhibition.”

VS: From all that I’ve heard and read, you had amazing levels of engagement.

CP: This participatory approach was really something new at the time. But it became massively influential. It was also huge fun. It has been my favourite job.

VS: There was no social media then, so how did you get people involved?

CP: It had so much press coverage, from the BBC children’s TV show Blue Peter to the Today Programme on BBC Radio 4. It was on absolutely everything. It went crazy. I had no idea that would happen. It was in the New York Times, in the Washington Post. British Airways had a film about it when you landed in London. Some people came straight from the airport. It was so wonderful.

VS: How exciting to be part of that – in fact, to have made that happen. Were you one of those children who was always making stuff happen, putting on plays or creating some kind of social scene?

CP: No. My parents were completely bewildered. They were really proud, but also really bewildered. I had always liked painting and making things, and my earliest memories are of doing stuff like that. I had a friend at school - who I think is the most creative person I’ve ever met – and we would spend hours and hours doing ridiculous projects, cooking something or making stained-glass windows out of macaroni.

VS: You clearly have a knack for getting people to agree to do things.

CP: I think I have a knack of bringing people together around an idea and making it happen. I think that’s my main skill.

VS: Is that something you can learn or be taught?

CP: I don’t know whether it’s something I’ve learned, but I can talk to anyone. And that really helps. And I know when to believe in an idea. That also helps. It’s mostly intuitive, gut feeling.

VS: But you also have to be good at communicating an idea.

CP: It’s important to be able to communicate what’s happening, but in a really simple way. For example, I did a project with an allotment association, a school, five artists, a chef and a gardener. It was about growing, harvesting, cooking and serving an alternative school dinner on the allotment to kids, their parents and friends. But we tried to key in the whole of the curriculum to an outside classroom. The question was: can you learn everything you need to learn in primary school through growing a dinner? It provides a lens for looking at different issues: it could be looking at childhood health and obesity, it could be looking at the relationship between the producer and the consumer; it could be looking at organic growing methods, or building new communities, reuniting agriculture and culture. But that’s not what you say. You say: “OK, we’re going to grow, harvest, cook and serve a school dinner, on an allotment.” And everyone gets that.

VS: So there’s a quick buy-in to the mechanics of what you are going to do and everything else follows?

CP: Yes, you say: “We’re going to close a bridge in central London and invite people to come and eat there.”

VS: That was the Feast on the Bridge.

CP: Yes, that was after the Museum Of. I did freelance jobs because I’d had my first child, Poppy. I did two things for Lift. Then I did Old Dog New Tricks, a project at the Roundhouse (then a derelict building in north London, now a major events venue), which was about testing out proverbs.

Clare Patey. Teaching an old dog new tricks. Installation view, Old Dog New Trick, Roundhouse, London, 2002. Photo: Tim Mitchell.

It was a bit mad – we had an old dog, and every night we tried to teach it a new trick. We had massive chairs and threw toast off them to see if they landed butter-side down. We had a horse that we tried to lead to water and make it drink. Every night it was something different.

Clare Patey. The toast always lands butter side down. Installation view, Old Dog New Trick, Roundhouse, London, 2002. Photo: Tim Mitchell.

Then I worked with the (thinktank) New Economics Foundation, creating Ration Me Up, a ration book like those from the second world war, but which showed you the carbon footprint of how you live. I did that and got very involved with Tipping Point, which was about bringing scientists and artists together to do projects around climate change. I did a big project with anthropologists with five different universities about the global trade in textile waste, called Everything Must Go. I did lots of freelance work, lots of small projects. I did stuff at the Southbank Centre. I did a project in Arizona about copper miners. And I did a Big Feast there. I did the launch of the Big Lunch in 2009.

Clare Patey. People and Ration Books. Photo: Tim Mitchell.

VS: But the artwork that has travelled the furthest and gained the most traction has to be A Mile in My Shoes. Where did that come from?

CP: It came out of the Empathy Museum series, but I was also thinking about public spaces, social spaces and the privatisation of those spaces in the public realm. And I thought, actually, the high street is at the centre of a community’s life, but it is also beginning to wane and small independent shops are going out of business, pushed out by big chains, and that’s been exacerbated by Covid. But when you talk to people about empathy, people either describe it as “walking in someone else’s shoes”, or “seeing the world through someone else’s eyes”. I thought: what if we opened a shoe shop, and you literally walked a mile in someone’s shoes and heard someone’s story?

Clare Patey. A Mile in My Shoes, with Help Refugees, Carnaby Street, London. Photo: Charlie Messenger.

We started in Vauxhall as part of the Thames Festival and, because we were right next to the river, it has lots of links with people who live or work on the Thames. We had a volunteer lifeboat worker and someone whose family had worked on the Thames for 400 years. We just began to go out from there, drawing on networks and what’s around there, such as the Royal Vauxhall Tavern, which has a big drag queen scene. It’s really geographical, about what was there and trying to be diverse in terms of age, gender, background and ethnicity.

VS: My recollection of that first Vauxhall showing is so vivid. I had been given the shoes of a woman who had orthopaedic issues, so they were big and clumpy, and as I strolled around, I heard her story – so much of which I can still recall vividly. It was tremendously immersive and moving.

CP: You embody the person in a way. You’re on this physical journey, but also, hopefully, on an emotional journey; you’re on your own, you’ve taken time out, you are just listening, it’s very intimate, but also quite playful.

VS: There’s something quite childish and also clown-like about putting on someone’s shoes. But the whole aesthetic of the shop – the shoe boxes, the container looking like a giant shoe box – was also really strong.

CP: I have always been very keen on getting the aesthetics right. Even if you’re working in a community setting, doing something really low key on a housing estate, there has to be an integrity to the whole thing so that everything you experience ties in. It’s really important to have high production values. There were some people involved at the early stage saying: “Maybe you could just listen to stories on your mobile phone.” But I said: “No, this rests on the quality of those stories, so you pay professionals properly, you record the story properly, that’s what you do.” The shipping container and shoe box were slightly happenstance: the Thames Festival said it needed to be at the side of the Thames. A shipping container was brilliant because it’s weatherproof and you can lock it up at night.

VS: That work has travelled all over the world. Why do you think it has had so much traction?

CP: Because it’s really simple and people get it very quickly. Every language we’ve done it in so far seems to have a very similar proverb, such as “walk a mile in someone’s coat”. As a model, it’s completely adaptable so you can make it about your own community or you can fit it into a wider, global sense. The reason it works is that it’s a powerful thing that involves people taking part as the storyteller and other people as the visitor, so it’s about who you’re attracting, and it’s playful and free and not appealing to a traditional arts audience.

VS: Do you feel optimistic, as the cultural sector comes back to life after lockdown, that there will be a growing demand for work that brings these major issues around social and environmental responsibility – which have really come to the fore during the pandemic – to life?

CP: I do think that there is a move towards hearing voices that you might not usually hear and if you read the Arts Council’s Let’s Create manifesto, that is its policy for the next 10 years. It really is about involvement, participation, everyone’s an artist, that whole thing. I also think that this is going to leave its mark. With the economic downturn, there are people all over the place out of work. We need to explore how art can be a catalyst, to have those conversations.

VS: When you look at how relevant all your early themes – climate crisis, plastic waste - still are now, what do you think happened in the intervening years? Did we all suffer some collective amnesia so that they dropped off the radar?

CP: The answer is I don’t know. But I wonder whether, at the beginning, we were looking at it in a simplified way – people at school were learning about saving the whale, for example. Climate change is such a huge thing. It’s what the philosopher Timothy Morton calls a “hyperobject”, because it’s so complex and there’s so much going on that we struggle to find a focus. But climate change is not the cause of anything, it’s the symptom of a whole way of living, so if you start to try to dismantle the whole thing, maybe you’re dismantling an entire way of life and capitalism and everything else. And it took some time for that to become clear. But at the same time there’s pushback, a whole lot of other stuff happening that is countering that, which is upholding the current system.

VS: Which surely makes that discourse in art all the more important. Finally, I love the way you use humour in your work. You have told me that your final dissertation at Central Saint Martins was on jokes. Tell me more about that.

CP: I think people don’t take humour seriously enough (laughter). What I mean is, people often don’t take you seriously if you approach the world with humour and yet I think humour allows you to look aslant at the world, in the way that artists often do, to reveal something hidden but universal.