Gerrit Dou, A Woman Playing a Clavichord, c1665 (detail). Oil on oak panel, 37.7 x 29.9 cm. Dulwich Picture Gallery, London.

Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

4 May – 4 September 2022

by DAVID TRIGG

Stand in front of Rembrandt’s Girl at a Window (1645) and you will soon see why the painting has been dubbed the “Mona Lisa of London”. A jewel in Dulwich Picture Gallery’s collection, the canvas depicts an anonymous young woman bathed in light as she gazes wistfully out of a shadowy window. Her beguiling appearance has led many to speculate on her identity; some have seen her as a servant girl, a bride or biblical character, while others have suggested a courtesan or even the artist’s lover. All can agree, however, that her gaze is utterly mesmeric. Rembrandt’s masterpiece is the cornerstone of this ambitious exhibition, which brings together a motley selection of artworks, from ancient to contemporary, to examine the enigmatic motif of “the woman in the window”, a theme with roots in ancient civilisations, but which still resonates today.

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, Girl at a Window, 1645. Oil on canvas, 81.8 x 66.2 cm. Dulwich Picture Gallery, London.

At nearly 3,000 years old, the earliest artefact here is a Phoenician ivory relief depicting a woman thought to be a temple prostitute peering from a window. Harlotry crops up again on a fourth-century BC wine bowl decorated with a scene from a Greek comedy; under the cover of night, two sleazy old men visit a finely dressed courtesan who watches from her window as one clumsily negotiates a ladder below. Exploring the theme of prostitution in the modern era is Marina Abramović’s Role Exchange (1975), for which the artist swapped places with a female sex worker from Amsterdam’s red-light district. Documented by photographs, the four-hour performance saw Abramović sit in the window of a brothel (an experience she described as “crushing”) while the prostitute replaced her at an exhibition opening. Though spanning millennia, each of these works challenges the objectifying gaze of those who reduce women to sexual commodities.

Bell Krater, Paestum, 360-340BC. Pottery, 37.2 x 36.2 cm. British Museum. © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

In the second room, the profane gives way to the sacred with Dieric Bouts’ The Virgin and Child (c1465), a radiant egg tempera panel painting depicting Mary nursing the infant Christ. Framed by an open window, the Virgin occupies a room draped with rich brocade cloth, while behind her is another window overlooking a city. Here, the Virgin is presented as the “window of heaven”, mediating between the terrestrial and celestial realms. The majority of works here, however, are grounded in the earthly world, with several drawing attention to the domestic sphere, which was long considered the most appropriate place for women. A subtle challenge to this is found in Isabel Codrington’s The Kitchen (1927), in which a woman, turning her back on her domestic chores, gazes longingly out of the window, perhaps dreaming of escape.

While many of the women portrayed in these works remain anonymous, often representing a female type or idealised woman, others are known by name. Botticelli’s portrait of the upper-class lady Smeralda Bandinelli follows Leon Battista Alberti’s recommendation that artists should depict their subjects as if looking out of an open window to draw attention to the framing of the face, even if Renaissance ladies would seldom appear in this way.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Smokin Jo, window, 1995. Unframed inkjet print, 208 x 138 cm. © Wolfgang Tillmans, courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

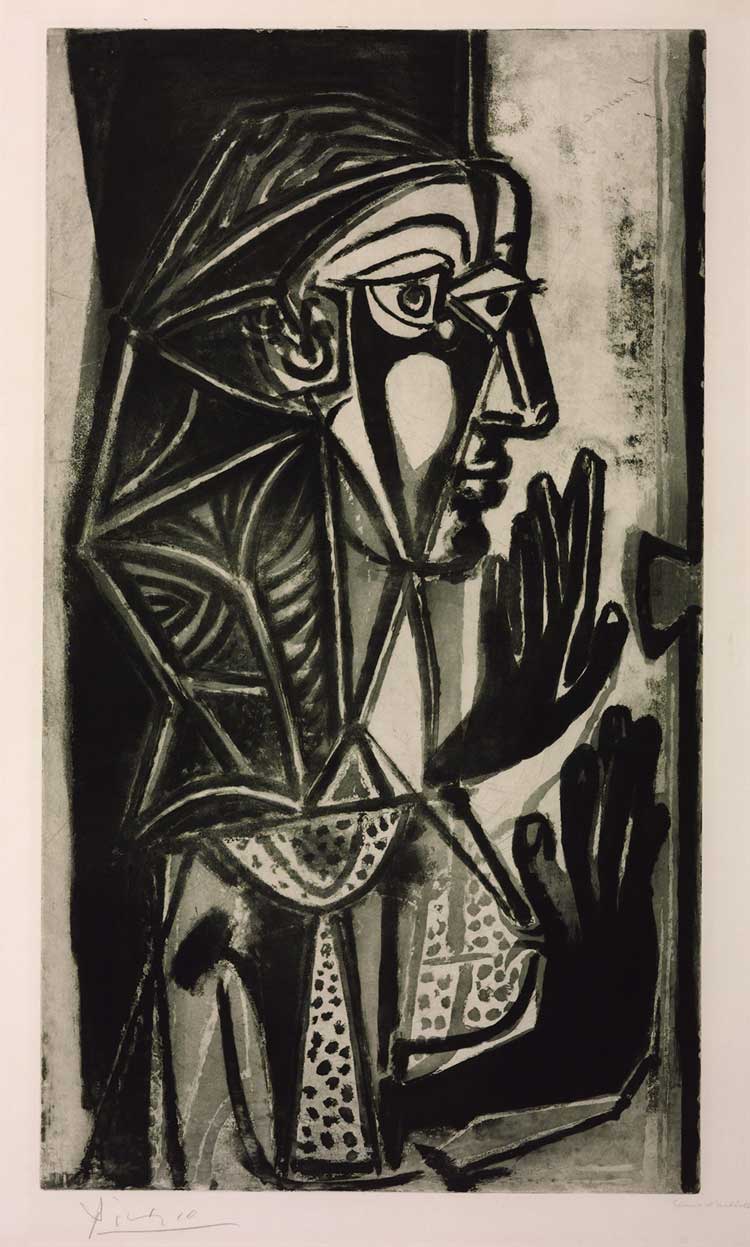

Pablo Picasso, La Femme à la fenêtre (Woman at the Window), 1952. Aquatint and drypoint, 90.2 x 63.5 cm. © Succession Picasso / DACS, London 2021. Photo: Tate.

Other women are credited as active participants in the creation of works. Take the 1995 photographic portrait of the British house and techno DJ Smokin’ Jo by Wolfgang Tillmans, who describes his subjects as “accomplices”. The DJ’s hands press against a window, a pose mirrored by Picasso’s partner Françoise Gilot in the adjacent print La Femme à la Fenêtre (1952); in both images the women’s postures suggest a sense of yearning, though where their desires lie are left for viewers to speculate. Conversely, we can easily surmise the thoughts of the two women separated by a window during the 2020 lockdown, photographed so sensitively by Simran Janjua.

Simran Janjua, Dadi's Love, 2020. Photograph © Simran Janjua.

The diverse ways in which “the woman in the window” has been reimagined across the ages is extraordinary, as is the way this show joins the dots between them. Sometimes works elicit empathy, at other times voyeurism, though all of them emphasise the relationship between the act of looking and being looked at. The motif’s openness to interpretation is certainly part of the appeal, yet several head-scratching moments cause you to wonder if it hasn’t at times been defined too loosely. Take Kudzanai-Violet Hwami’s masterful oil painting of a young Zimbabwean girl, Tsitsi (2022). The wall label tells us that “a vertical white line disappearing behind her head indicates a window”, though this is disputable. Even if it were a window, its presence seems merely incidental rather than integral to the work’s meaning. Indeed, elsewhere “the woman in the window” occasionally becomes “the woman near the window”, or even “the window without a woman”, as with Isa Genzken’s Fenster (1990), a brutalist concrete window frame that sits in the mausoleum on a roped-off plinth.

Louise Bourgeois, My Blue Sky, 1989-2003. Gouache, watercolour, ink, pencil, coloured pencil and paper mounted into a wood and glass window frame, 70.5 x 58.4 x 15.9 cm. © The Easton Foundation / VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2021. Photo: Christopher Burke.

Genzken’s minimal sculpture is echoed by Rachel Whiteread’s Untitled (For WHP) (2015), a mesmerising translucent grey-blue resin cast of a window through which we see not the gallery but a wall of bricks. Hanging nearby, Louise Bourgeois’s My Blue Sky (1989-2003) incorporates a real window salvaged from her Manhattan home. With broken panes and peeling paint, the dilapidated structure oozes history while framing a semi-abstract landscape of white, red and pink mounds that evoke the curves of the absent female form. These works, where the presence of a woman is only implied, demonstrate just how broadly the theme is interpreted.

Tom Hunter, Woman Reading Possession Order, 1997, from the series Persons Unknown. Cibachrome print mounted on board, 29.7 x 21 cm. Courtesy the artist Tom Hunter.

The show’s title conjures one glaring omission: Johannes Vermeer’s Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (c1657–59), a meditative painting in which the open window represents the woman’s desire to be liberated from her domestic constraints and united with her lover. It serves as inspiration for Tom Hunter’s photograph Woman Reading a Possession Order (1997), which approximates Vermeer’s composition, substituting the sumptuous interior with that of an east London squat, and the love letter with an eviction notice. The warm sunlight illuminating the young mother’s impassive face suggests hope amid despair; another example of how fertile the simple juxtaposition of a woman and a window can be.