National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

14 February – 10 June 2018

by ANNA McNAY

If one had to pull out the key themes or threads running through the work of the German expressionist painter and printmaker Emil Nolde (1867-1956), they would certainly include flowers and gardens, dancers and cabaret singers, races and types, religious imagery, and then, and perhaps overarchingly, colour and light. “Colour is strength, strength is life,” he is known to have said, and he certainly used colour as the primary vehicle for expressing himself and bringing his canvases and pages vibrantly to life. So much so, in fact, that entering the first room of the National Gallery of Ireland’s retrospective, which draws its title from this quote, the paintings, set against dark blue (and later red) walls, seem positively to glow, as if lit from within. “Every colour harbours its own soul, delighting or disgusting or stimulating me,” Nolde further wrote. “Yellow can depict happiness and also pain. Red can mean fire, blood or roses; blue can mean silver, the sky or a storm.”

Emil Nolde. Rain over a Marsh. Watercolour on rice paper, 42.1 x 53.7 cm. © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll. Photograph © National Gallery of Ireland

The vast sky and flat land- and seascapes, with their dramatic and stormy light, around the village of Nolde, on the German-Danish border, where Emil Hansen (he adopted the name of his birth-village in 1902) was born, indeed influenced the young artist greatly. He was forever drawn to return to this region, ultimately building a modernist house and studio in the nearby Seebüll, where the foundation in his name, from where most works in this exhibition are loaned, is now based. This location, and Nolde’s complex relationship with it, inspired him deeply, but also posed complicated questions of national and cultural identity. Following the Treaty of Versailles, national borders were redrawn, and Nolde’s hometown became part of Denmark. Nolde rejected this “foreignness” and became increasingly nationalistic, later to the extent of becoming a fervent subscriber to the National Socialist party. By 1937, however, he was labelled as “degenerate”, going on to have more than 1,000 of his works – more than by any other artist – denounced, and 33 of his paintings were included in the Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich that same year. Despite his strong roots, Nolde remained a perpetual outsider.

Emil Nolde. Aboriginal man swimming, 1914. Watercolour on paper, 38.3 x 50 cm. © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll.

It is perhaps not surprising, then, that so many of his works express an interest in types – a painterly project akin to August Sander’s immense photographic one. Rarely do the titles of Nolde’s paintings ascribe specific identity to his sitters, even when they are known to depict friends, relatives, or members of the local community. Thus the faces in Frisians, Man and Woman (1910) gaze out at us anonymously, an everyman and everywoman, painted thickly, almost aggressively, in the manner of a roughly hewn woodcut. Nolde had, in fact, been apprenticed as a woodcarver in his teens, going on to work in a furniture factory. This form of woodcut was, furthermore, the archetypal German form of printmaking at the time – again reflecting the entwinedness of Nolde, his art and his national identity.

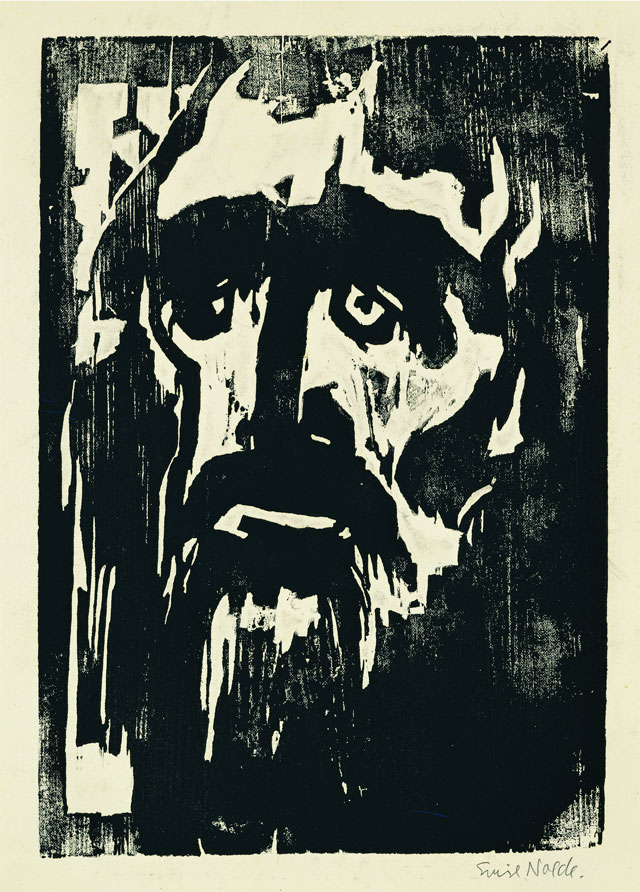

Emil Nolde. Prophet, 1912. Woodcut on paper, 29.8 x 22.1 cm. © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll.

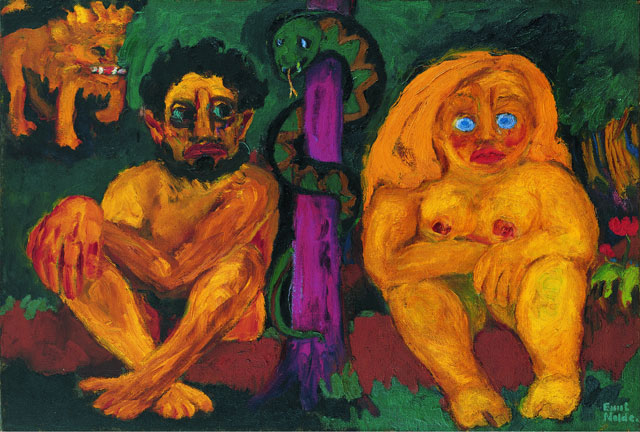

An actual woodcut on display is Prophet (1912), one of Nolde’s better-known works, made following a bout of serious illness in 1909, after which he experienced a deepened sense of spirituality and began to work more closely with religious themes and iconography. These works were not generally popular before the first world war, but, after Germany’s defeat, appetites changed and they came to epitomise expressionism. The primitive, yellow figures of Adam and Eve in Paradise Lost (1921), for example, drawn as if by a child, appear (in Nolde’s own words) “contrite and perplexed, staring into the future, [as] expelled and suffering ancestors of humanity”.

Emil Nolde. Paradise Lost, 1921. Oil on sackcloth, 106.5 x 157 cm. © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll.

While Martyrdom I, II and III (1921), with their clear references to Grünewald, evidence Nolde’s strict upbringing by a staunch, church-going, Protestant family, he was not always wholly pious in his referencing of Christianity. Ecstasy (1929), for example, originally intended to depict the Virgin Mary at the moment of being touched by the Holy Spirit, is now a riot of albeit ecclesiastical purple set against the shocking complementary orange (contrasting complementary colours is a regular feature in Nolde’s work) of the angel figure’s hair. The Mary figure’s eyes are a luminous turquoise – likewise a recurring colour choice for eyes, shared not only by Eve (in Paradise Lost), but by Nolde himself, in a self-portrait from 1917. Most shocking, however, is the arch of this figure’s back, in the throes of what might far better be described as wanton pleasure than immaculate conception. This is one of the most striking paintings in the exhibition and it remains imprinted on the retina long after stepping back outside into Dublin’s grey April showers.

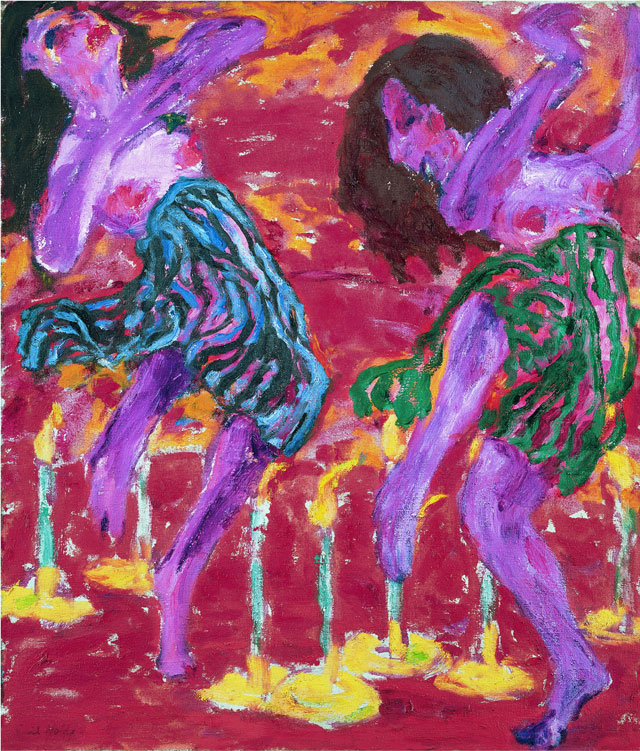

Emil Nolde. Candle Dancers, 1912. Oil on canvas, 100.5 x 86.5 cm. © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll.

This sense of the physical, of bodily animation, is something captured at its peak in Nolde’s works made in the theatres and cabarets of Berlin, where he and his Danish-performer wife Ada Vilstrup spent six months of each year in the early 1900s: her performing, him painting and sketching. Singers, dancers, musicians – his work of this era might be compared favourably to that of Henri Toulouse-Lautrec. Even here, however, Nolde is the observer looking in from the outside: in the foreground are dark figures, seen from behind, as they face towards the stage where, at a distance, the colour is set free, sequins and satins shimmering brightly under the spotlights.

Emil Nolde. Exotic Figures II, 1911. Oil on canvas, 65.5 x 78 cm. © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll.

It was in Berlin, too, that Nolde was a frequent visitor of the ethnographic museum, where he developed his interest in primitive arts and crafts, as can be seen, for example, in the semi-enchanting, semi-grotesque Exotic Figures II (1911), depicting a North American kachina doll and two cat-like sculptures. It was an era when theories of race were prevalent and, keen to “get to know the unknown”, Nolde (only semi-officially, since Ada also accompanied him) set off with a medical-demographic expedition on the Trans-Siberian railway for German-New Guinea in the South Seas. Along the way, he painted Three Russians (1914), extending his interest in types to that of men from different countries and continents, and, on arrival, producing many paintings of the natives, including Manus Men (1914), and quickly sketched watercolours, made of the aborigines as they attended medical examinations. “I paint and draw and try to capture something of the original quality of the people,” Nolde wrote to a friend. “I know of no other artist, except Gauguin and myself, who has produced anything of permanent value out of the endless bounty of this primitive life.”

,-1913.jpg)

Emil Nolde. Junks (red), 1913. Watercolour on paper, 24 x 33.2 cm. © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll.

Nolde also painted the tropical island, the sea and the Chinese junks, capturing their movement and the breeze in their sails with watery brushstrokes every bit as bright and vivid as his thickly impasto oils. Several decades later, during the second world war, when the Nazis banned him from working with – or even buying – oil paint, Nolde turned almost entirely to watercolour. This exhibition brings together a fascinating selection of works from this period – the so-called “Unpainted Pictures” – made by applying paint to wet paper and letting the colours bleed, before discerning and delineating shapes and figures within this puddle of colour. Among the fairytale creatures and hobgoblins – a curious insight into the contents of Nolde’s mind – a powerful image of an ice-skater stands out, bent forward, hands clasped, gliding serenely across the frozen lake. “Anything,” noted Nolde, “can be painted as long as it lies within the possibilities of colour.”

Emil Nolde. Women in the Garden, 1915. Oil on canvas, 73 x 88 cm. © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll. Photograph © National Gallery of Ireland.

At their home in Seebüll, Nolde and Ada cultivated a garden, laid out as the entwined initials E and A, and many of his later paintings are inspired by this oasis of colour and security. Women in the Garden (1915), thought to depict Ada and a neighbour, belongs to the National Gallery of Ireland’s own collection and was something of a starting point for the exhibition. The final room is so adorned with floral-filled canvases that it has almost become a garden itself. Large Poppies (Red, Red, Red) (1942), painted when Nolde was 75, is such a truly exultant celebration of colour, it perfectly sums up his life’s work – carrying with it also the sombre associations of these fragile flowers, a silent reminder of the turbulence of the times through which Nolde lived.

Emil Nolde: Colour Is Life travels to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, 14 July - 21 October 2018.

-1942.jpg)

Emil Nolde. Large Poppies (Red, Red, Red), 1942. Oil on canvas, 73.5 x 89.5 cm. © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll.