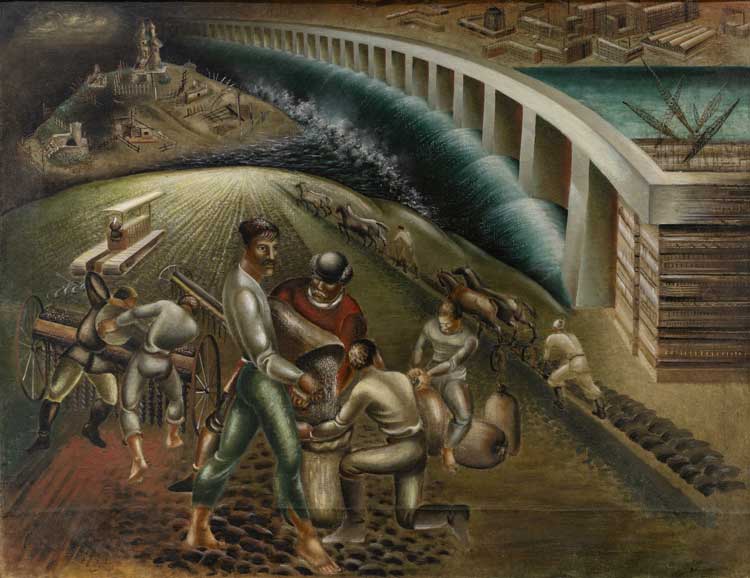

Jerzy Hulewicz, Charge, 1932. Oil on canvas. 132 x 197 cm. National Museum in Warsaw, Poland.

Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin

30 November 2023 – 21 April 2024

by JOE LLOYD

Queen Victoria would not be amused. The Irish artist Niamh McCann has attached a bronze nose to a blown-up photograph of her former monument in central Dublin. Her new hooter is a copy of a 1949 marble carving of the Irish revolutionary Michael Collins, a contested figure who was assassinated in 1922 after supporting a treaty that would have kept Ireland as a “free” dominion of the British Empire. The Victoria sculpture had been erected 1908 in front of Leinster House, now seat of the Oireachtas, Ireland’s parliament. What one politician called “the effigy of a lady whose name stank in the nostrils of past generations of Irishmen” had to go.

Yet it took until 1948 to be removed, first to the Royal Hospital Kilmainham in Dublin’s suburbs – pieces of the shattered plinth are still strewn around the formal gardens – and then in 1986 to Sydney, where it stands today, appropriately outside a shopping centre called the Queen Victoria Building. One city’s bane was another’s boon. The splendid 17th-century Royal Hospital also found a new purpose. Since 1991 it has been home to the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA). Once a home for retired soldiers of the colonially run Irish army, it later became a potential site for the independent country’s parliament.

Jēkabs Kazaks, I laid my head on the boundary line, 1918. Tempera on board, 25 x 45.5 cm. Collection of the Latvian National Museum of Art.

There can be few more suitable locations for Self-Determination: A Global Perspective, an enormous new exhibition that examines the role of art in shaping national identity in the aftermath of the first world war. This was a turbulent time for nationalism. Four empires had expired. Others were weakened. New nations arose from the tumult and sought to define themselves against their former overlords. IMMA’s purview is not quite global: the focused countries tend to cluster around the Mediterranean and the Baltic seas. But it is still heroic in scope. The exhibition’s team reached out to specialists and institutions across numerous countries, and secured loans of works seldom seen outside their country of origin. There are also several new commissions.

The term self-determination was introduced into political discourse by the US president Woodrow Wilson in 1919. He promoted the idea that a group of people were eligible to create an independent state, as long as they were not a territory or colony of the US and its allies. Several such as Ireland attained nationhood regardless. And often with that newfound status came a need to create a national visual culture. As well as the destruction of the previous regime’s monuments, that often involved a repurposing of the old. The exhibition contains a cabinet of overprinted stamps from Armenia, Ireland and Ukraine. A new phrase or text is printed atop the old, which is both present and effaced.

Onufriy Biziukov, Sawmills, 1930-31. Oil on canvas, 92 x 125 cm. NAMU National Art Museum of Ukraine.

Many new states faced a tension between revivals of the precolonial past and a forward-facing modernism. Egypt’s architects embraced a style drawing on ancient mausoleums, while its modernising politicians used the same distant past as a justification for campaigning against Ottoman-era additions such as the veil. In Turkey, there was a trend towards a modernist aesthetic that severed the country from the Ottoman empire. German architects were brought in to build Ankara; the propaganda magazine La Turquie Kemaliste (1934-49) featured architectural illustrations resembling Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.

Self-Determination contains an abundance of different approaches. Ireland’s trailblazing Abbey Theatre is largely associated with haut bourgeois but allowed works from varied parts of the political spectrum. The Riga Workers’ Theatre (1926-34), represented here with photographs and a model of a set, was an explicitly socialist group. The exhibition also acknowledges the difficulty in the term self-determination itself. Turkey, an imperial capital that resisted a projected allied partition, is unique in the exhibition in having never been successively occupied by another power; today, it houses groups that seek their own self-determination as individual states.

Dmytro Vlasiuk, Dniproges Dam, 1932. Oil on canvas, 118 x 150 cm. NAMU National Art Museum of Ukraine.

The exhibition also reveals numerous commonalities, in particular across Europe and through the medium of painting. Artists in these new countries had the chance to help define a national aesthetic; they also had the chance to become a national icon. It was also a period where the stranglehold of Parisian post-impressionist broke, making room for a plurality of styles. A stretch of the exhibition examining labour, construction and infrastructure as an artistic theme shows a vast difference of approaches. In Ukraine, Onufriy Biziukov depicted sawmill loggers as hulks whose attire matches the hues of their homeland, while for Dmytro Vlasiuk the construction of the Dnieper Dam (1932) could stand as background for agricultural workers.

For those countries once subsumed into larger empires, the need to define a particular tranche of land as their own stands at the core of national self-determination. Further sections look at landscape as the site of both agricultural and symbolic self-sufficiency. The curators have unearthed works by numerous fantastic painters, many of whom deserve greater recognition. Tone Kralj eked grand drama from Slovenian rustic life in a style influenced by new objectivity. Serbia’s Jovan Bijelić turned the country’s interior into cavernous expressionist landscapes, while Estonia’s Konrad Mägi imbued his country’s lakes with a spiritual inward glow. Artists even staked a claim on imaginary lands: Jack B Yeats, brother of the poet, contributes a fantastically strange 1937 scene of a horse race in Hy-Brasil, a mythical island to Ireland’s west.

Seán Keating, Men of the South, 1921-22. Collection Crawford Art Gallery, Cork. © The artist's estate.

Similarly rich is a room that explores moments of assembly and celebration, from folk dancing to monastic orgies, as a way to integrate a people. But the exhibition makes it clear that the birth of a nation has its ravages. One room juxtaposes Seán Keating’s Men of the South (1921-22) and Jerzy Hulewicz’s Charge (1932-39). These oil paintings both celebrate armed struggle. The first captures the IRA in a naturalist style, a band of brothers fighting for liberty. The latter applies futurist energy to the Polish Legions, formed in the first world war. Their casualties allowed their founder, Józef Piłsudski, to demand independence for Poland. Neither painting shows the enemy armies, nor the civilians displaced to create a new state.

Jerzy Hulewicz, Charge, 1932. Oil on canvas. 132 x 197 cm. National Museum in Warsaw, Poland.

The exhibition’s contemporary pieces, several of them new commissions, often further puncture the glorification present in the historical works. Alan Phelan’s irreverent Eamon Often Spoke in Tongues (2007) has the head of eventual Irish president Éamon de Valera extend a twisted tongue, a reference to the way popular phrases have been falsely attributed to him. Turkish artist Dilek Winchester’s On Reading and Writing: Reading from the Three Texts (2007) features blackboards displaying three texts, in the Armenian, Arabic and Greek alphabets: the three most commonly used in Turkey before 1928, when Kemal Atatürk installed the Latin alphabet. A country became illiterate overnight.

Others strike an elegiac tone. Ursula Schulz-Dornburg’s series Train Stations of the Hejaz Railway in Saudi Arabia (2003) captures the 820-mile route connecting Damascus to Mecca. Too expensive for the ailing Ottoman empire, it was part-funded by donations from across the Muslim world. It opened in 1908. A few years later, TE Lawrence and Bedouins began assaulting its stations, forcing it to close in 1920. Attempts to revive it have foundered, in no small part due to discord between the nation states that followed. Nationhood is a messy business, an idea that IMMA explores with uncompromising clarity.