Kokeshi artisan Okazaki Ikuo at his studio in Zao Onsen, Yamagata Prefecture. © Okazaki Manami.

William Morris Gallery, London

23 March – 22 September 2024

by BETH WILLIAMSON

If you haven’t come across the Mingei movement, now is the time to visit a fabulous new exhibition at the William Morris Gallery. The gallery is well known for being dedicated to the life and work of William Morris (1834-96), a designer, craftsman and radical socialist. It is entirely appropriate, therefore, that it is hosting the largest ever exhibition in the UK devoted to Mingei – a folk-craft movement that emerged in Japan in the 1920s and 1930s. Mingei was developed by Yanagi Sōetsu (1889-1961), a Japanese philosopher and aesthete along with potters such as Hamada Shōji (1894-1978) and Kawai Kanjirō (1890-1966). Visiting Korea in 1916, Yanagi developed an appreciation for local craft and established the Korean Folk Crafts Museum in 1924. Back in Japan, he built a collection of Japanese folk pottery from the Edo and Meiji periods, eventually going on to found the Japan Folk Craft Museum in Tokyo. He was also editor of the journal of the Japanese Folk Arts Association (1931-51). In 1952, he was invited to Black Mountain College where he taught alongside Hamada and Bernard Leach (1887-1979). It is not difficult to imagine how this wide range of influences may have impacted on Yanagi and Mingei.

Hamada Shōji demonstrating at Scripps College, California, 1953. From the collections of the Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts.

The term Mingei means the art of the people. It takes traditional craft objects, unnamed artisans and a pared-back lifestyle, and attributes them with ideas of cultural value and aesthetic purity. The important point to note about this exhibition is that it does not only look to Mingei as a historic movement, although that would be fascinating enough as a subject in itself. This exhibition exceeds a historic remit, considering Mingei as a set of principles that retain pertinence in contemporary craft and consumer manufacturing across the globe. Beginning in a period of rapid industrialisation in Japan, Mingei developed alongside the British Arts and Crafts movement and within the context of Pure Land Buddhism in Japan. If Mingei tends to be viewed as a broadly Japanese aesthetic, the exhibition shows the importance of objects made by the indigenous Okinawan and Ainu people of Japan, and of Korean objects too.

-National-Museums-Scotland-A1909.jpg)

Ikupasuy (Ainu language, prayer stick), uknown Ainu maker, Hokkaido, Japan, 19th to early 20th century. © National Museums Scotland.

In the first part of this three-part exhibition are the 19th-century craft objects from which Mingei took its inspiration. Ceramics, wooden kokeshi dolls, kimonos, stitching and other objects all feature as points of reference. A sake flask, complete with distinctive painted horse decoration, typical of Ōbori sōma ware from the Fukushima prefecture, is a delightful object. Close by, a glazed stoneware storage jar from the Miyagi prefecture is made from coarse local clay with a dynamic namako glaze. Ceramic teapots, bowls, jars and cups come together with textiles and other materials to convey a sense of the simple and practical matter of making and using everyday objects. It would be easy to romanticise the beautiful effects of boro, a patchwork fabric made from recycled scraps of fabric. A boro bodok (sheet) shown in this exhibition would have been spread out on a bed of dry leaves on the floor, for sleeping or use during childbirth. Its attractive appearance is accompanied by a sharp reminder of the reuse-recycle hardships and poverty of life in rural communities in Japan.

Shigoto-gi Work Clothes. Late Edo to early Showa period, 1800s-1950s. Collection of Chuzaburo Tanaka.

Shigoto-gi (work clothes) using the boro form are seen, too, alongside other garments, such as kimonos, using kasuri (a complex technique of weaving selectively predyed yarns to create a design) or an Ainu attus (robe) made from elm bark, and a sashiko farmer’s coat, sewing together layers of fabric with running stitch, all connecting to Yanagi’s belief that beauty in such objects was always linked to its use.

-National-Museums-Scotland-A1929.jpg)

Bowl in the style of Chinese Jun ware, Japan, by Kawai Kanjirō, early 20th century © National Museums Scotland.

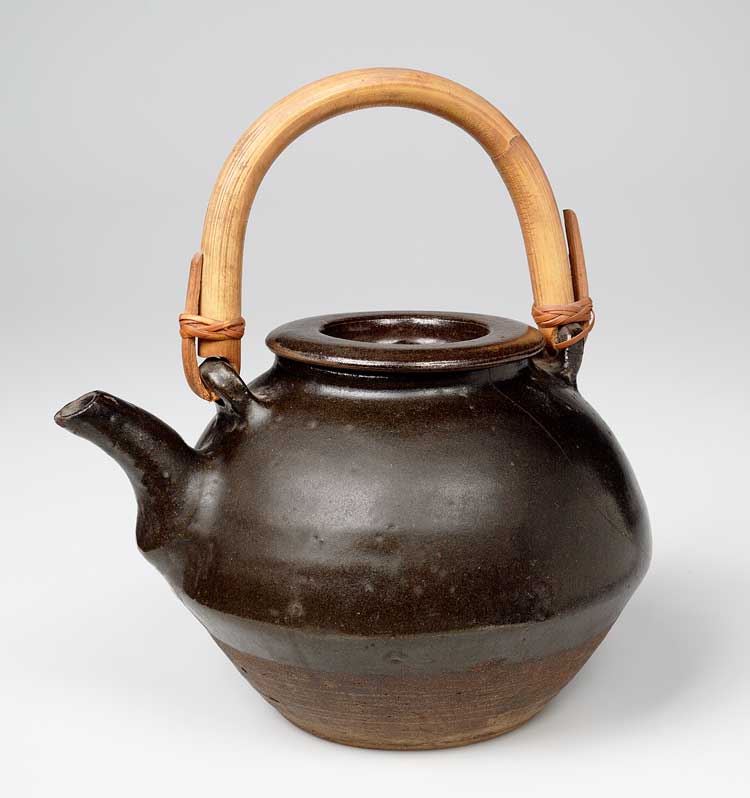

Next, the exhibition turns its attention to the emergence and development of Mingei in the 20th century. It was, in a sense, a counterpoint to the rapid industrialisation and modernisation that characterised Japanese society at the time. It was Yanagi, along with Hamada and Leach, who championed the idea of art without heroes and Mingei thrived under their attention. A glazed earthenware bowl by Kawai Kanjirō (1890-1966), who, in the spirit of Mingei, never signed his work, shows the striking blue and purple glazes of Chinese Jun ware. A stoneware white slip teapot with painted decoration by Minagawa Masu (1874-1960) is one example of how artisans devoted their lives to Mingei. In Mashiko, Minagawa began painted pots when she was just 10 years old and throughout her working life decorated hundreds each day. Yanagi appreciated her work, not for its individual artistic skill, but for its beauty which, he believed, stemmed from the pure transmission of tradition through repetition.

Teapot with a tenmoku glaze and bamboo handle, unknown maker, Japan, 1934. From the collections of the Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts.

Finally, the exhibition looks to contemporary versions of Mingei where forms may have changed but core aesthetic and philosophical ideals and values still hold strong. Look closely at some contemporary brands such as Muji or artists such as Theaster Gates (b1973) and the spirit of Mingei glimmers there still. Gates’s pots are part of a practice that places Mingei at its centre. After he studied pottery in the Japanese city of Tokoname, Gates regarded Mingie as Japan’s response to westernisation and he developed the idea of Afro-Mingie in order to explore the relationship between Black identity, Japanese folk craft and the regeneration of marginalised communities. In works such as Preservation Exercise #3 (2021), the large earthenware and tar vessel shown in this exhibition, Gates uses everyday materials, including the tar his father used in his roofing business, to link his artistic practice to the daily work of unknown and unnamed crafts people.

-Itoshiro-Yohin-Ten.jpg)

Hirano Kaori dyeing fabric at Itoshiro Yōhin Ten, Gifu Prefecture, 2023. © Itoshiro Yōhin Ten.

The contemporary brand Muji is included here too. Mujirushi Ryōhin (no brand quality goods), or Muji, makes simple affordable everyday goods and is a global brand. Itoshiro Yōhin-ten is a startup clothing company based in the mountains of Gifu prefecture and making ecologically conscious clothing using natural materials and traditional forms. A stylishly designed cooking pot in iron and wood from the family-run Kamasada ironworks sits next to a wooden champagne cooler, handcrafted in wood in the manner once used for everyday containers for essentials such as rice or water. These two beautifully designed objects are now a luxury rather than a necessity. They seem to turn the ideals and principles of Mingei on its head, subverting its purity of purpose. However attractive their design, they veer from that tradition in important respects, even if they cling to aspects of its simplicity.

-Victoria-and-Albert-Museum,-London.jpg)

Bowl, Raku type earthenware with clear glaze over decoration painted in enamel colours, Japan, by Tomimoto Kenkichi, 1912. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

All three parts of this exhibition together tell the story of Mingei – before, during and after, if you like. More than just a presentation of quotidian objects, the narrative itself is a complex one, inflected by the cultural, social and political realms of 20th-century Japan and beyond. The take-away message of the exhibition matches that of Mingei – value the simple, the quotidian, the unnamed makers. Don’t ignore traditional materials and methods, but develop them anew, moving things forward, supporting the everyday aspects of human life and finding beauty in that, where ever it might be.