Kaye Donachie in her London studio. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

by ANGERIA RIGAMONTI di CUTÒ

Kaye Donachie (b 1970, Glasgow) is a time traveller of sorts, sifting through history in search of female artists and performers, some now more remembered than others, to re-evoke in a different temporal dimension. Drawing on written and photographic archival remnants, she fashions imaginary “portraits” of her subjects, though for all her work’s visual and literary references to personal and social histories, Donachie is primarily concerned with the act of painting, each face a canvas within the canvas, a stage for gestural expression. Her painterly world is claustral, designed with a vaporous, glaucous palette, her subjects spectral – by her own definition – and seemingly unaware of a viewing presence, making the viewer feel intrusive, almost voyeuristic. In addition to showing her own works in Song for the Last Act, at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, Donachie has also conceived an assemblage of modernist paintings and drawings from Pallant House’s top-notch collection, forming a dialogue with her own intimiste quasi-portraits.

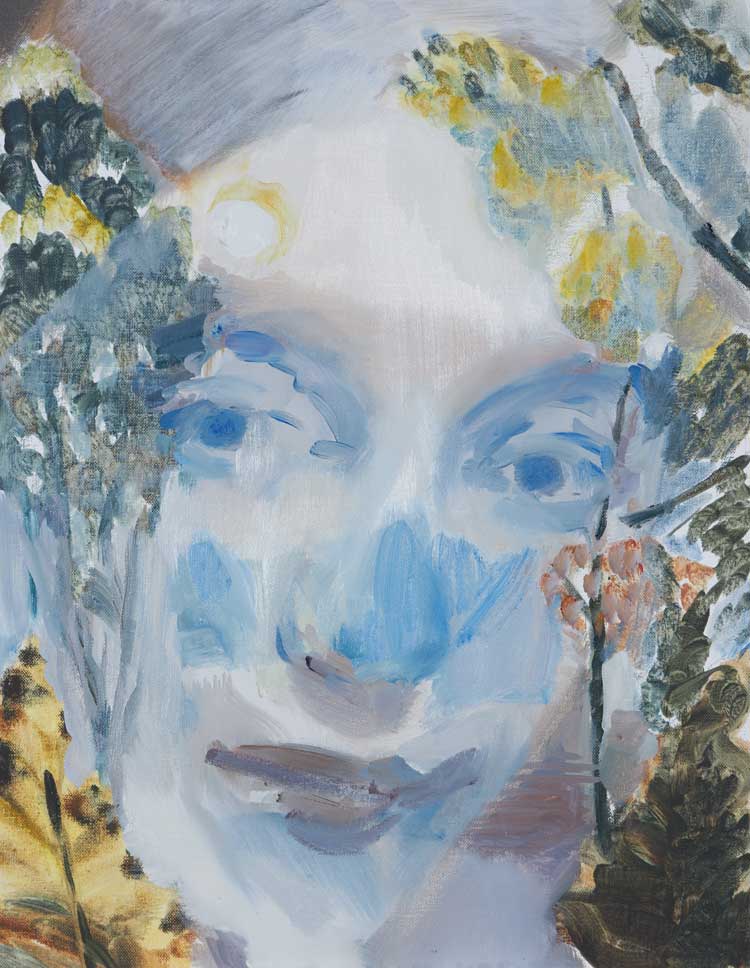

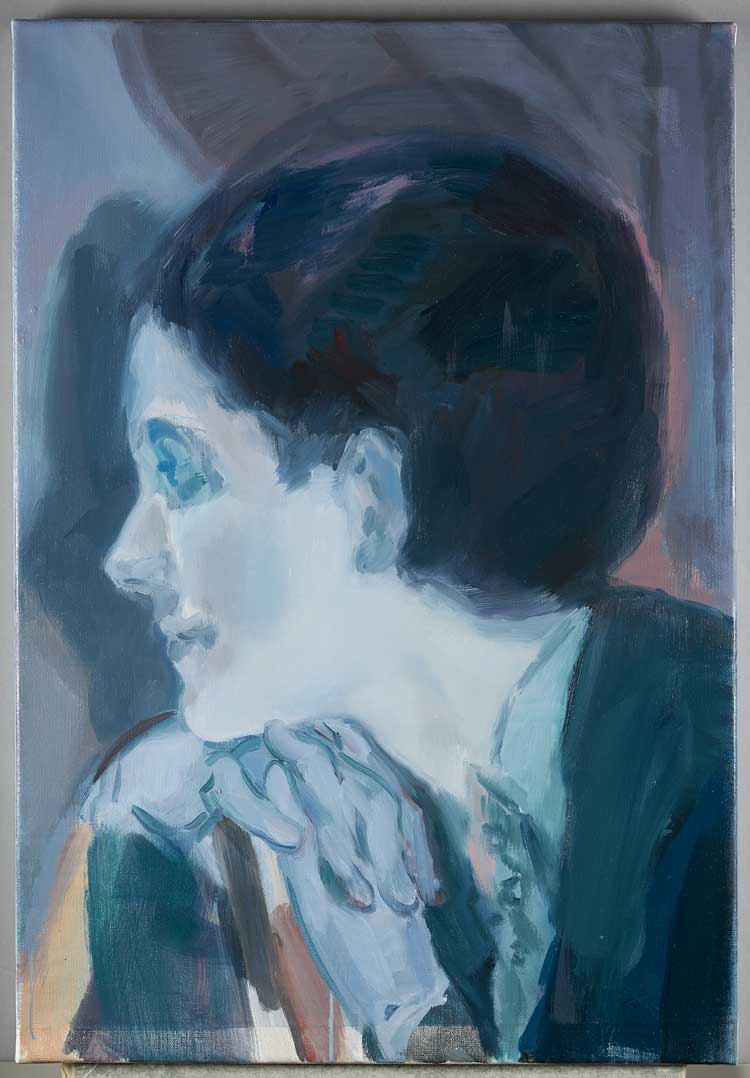

Kaye Donachie, Notes shift, 2023. Oil on linen, 80 x 60 cm. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London. © Kaye Donachie. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

The other voice within the chorus that resounds through the museum’s galleries is Gwen John, the subject of a biographical exhibition, and several reviews have considered the rapport between the two artists. Donachie, however, declined to comment on whether John’s presence had informed the shaping of her own show, or her installation of other artists’ works.

Donachie responded in writing to Studio International’s questions about her own exhibition as well as her curation of paintings and drawings in the Pallant House collection.

Angeria Rigamonti di Cutò: You centre your images and texts on a predominantly modernist cast of female performers, artists and writers, both in the portrayed figures and the poetry you cite in your titles. Have you considered referencing women from other historic periods, or is there something about the context of the first half of the 20th century that compels you to remain there – perhaps a sense that women were becoming more self-defined then?

Kaye Donachie: As you mentioned, early 20th-century figures such as Nusch Éluard, Lee Miller, Iris Tree and Maria Lani have remained important cultural touchstones in my work. Through their aesthetic vision, writing and art, they redefined the role of the muse and this has been inspirational.

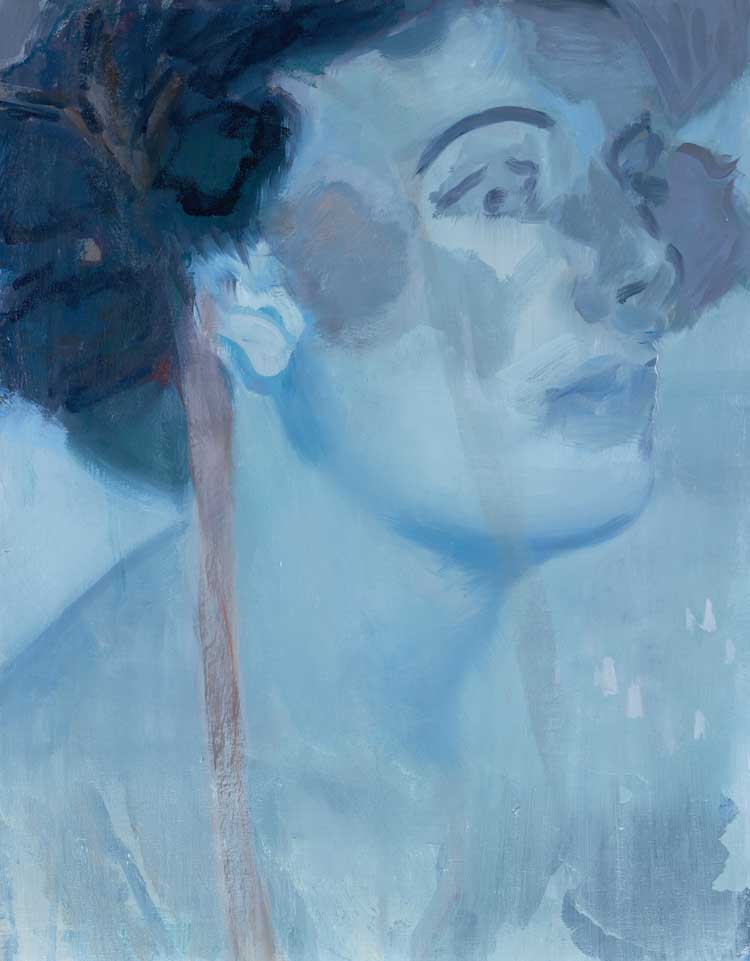

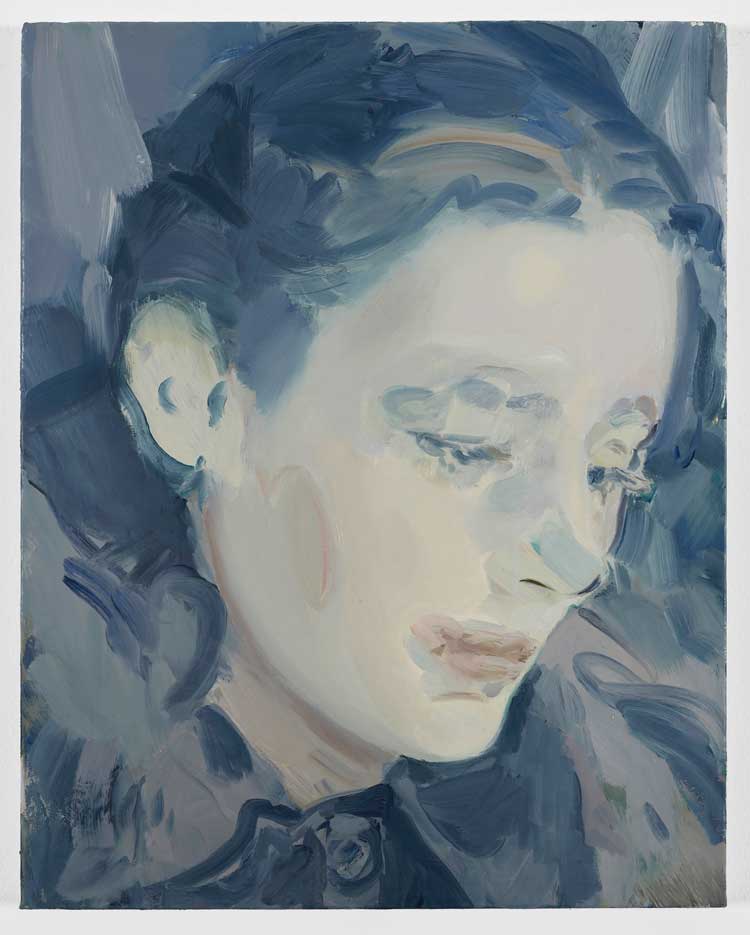

Kaye Donachie, To echo, 2023. Oil on linen, 46 x 40 cm. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London. © Kaye Donachie. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

My interests, however, are not limited to a specific timeframe. The poem More Than Pure Form (1971) was written by Rena Rosenwasser and included as the text for Silent as Glass, my show at Maureen Paley in 2018, alongside a title taken from an Iris Tree poem. I enjoy connecting voices past and present. My inspiration draws from diverse sources, discovering stories and biographies of individuals from different eras, interpretating alternative narratives within the painting. I am curious about liberated modern thinkers with sparse biographies. In my work, they can become somewhat fictionalised characters or protagonists, allowing me to explore within the painting an interpretation of different narratives.

All of this is figured through painting, I hope to portray an intimate revision of these characters, redeeming and conversing with images through the sensual, eroticised, visceral quality of paint. I will often merge histories and archives to allow space for re-interpretation and emotive ideas.

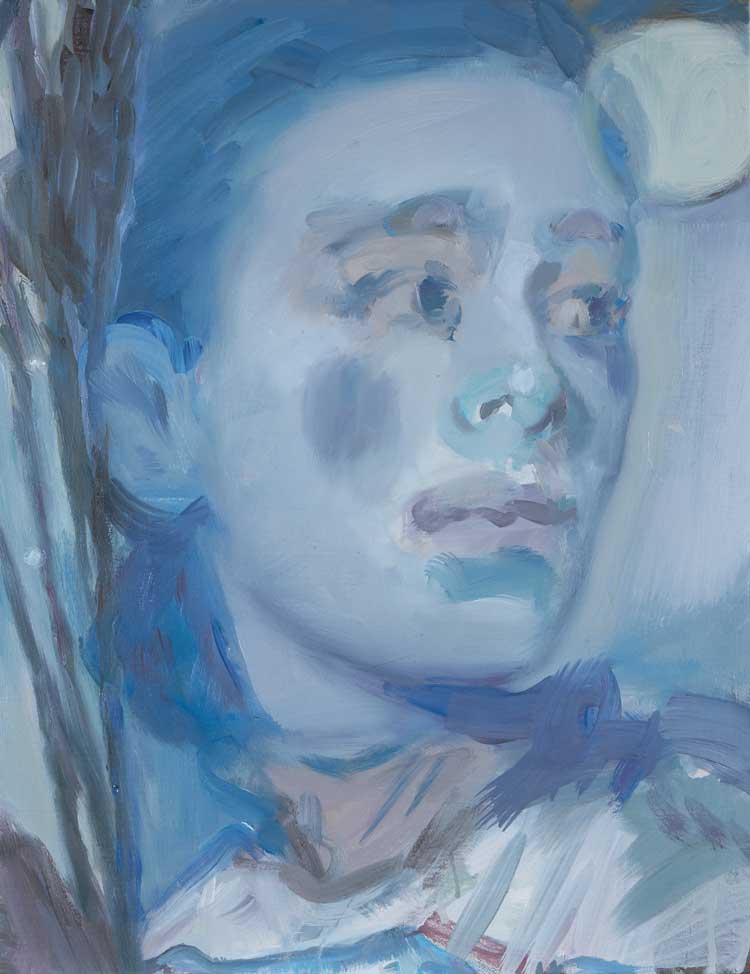

Kaye Donachie, Dark renewing, 2023. Oil on linen, 46 x 36 cm. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London. © Kaye Donachie. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

ARC: Poetry is a key component of your painted world, with quotations acting not just as titles but as a kind of textual evocation of thoughts and atmospheres. You’ve also written your own poetry, as is the case with your composition Song for the Last Act, the title taken from a work by the American poet Louise Bogan. Why did you decide to create your own texts; was it to better control the particular aura you want to evoke, whether with paint or words?

KD: Poetry is very important to how I think about images and how I want to create atmospheres and affinities using paint. It sets a tone within the work, and I use it to reimagine moments in time. I make poetic decisions, directing how paintings can work together as part of a tableau. I will collage fragments of women’s avant garde literature to make personal interventions, hoping that these compilations introduce a sense of time and place. My poem titled Song for the Last Act, which I envisaged as an extension of this approach, is also a line from a Louise Bogan poem. Using the titles of my paintings and the cut-up technique or découpé, I structured what I consider an elliptical poem. This was a means of reimagining past and present descriptions. The poem acts as an echo of words, creating an abstract script that allows me to expand my references.

Kaye Donachie, Like walls the mirrors stand, 2023. Oil on linen, 60 x 46 cm. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London. © Kaye Donachie. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

ARC: Jean Cocteau said of one your historical points of reference, the performer Maria Lani: “Madame Lani is painting me!” You are, of course, painting from photographs rather than live models and not creating portraits as such, but do you ever have the sense that your subjects are painting you?

KD: Painting is certainly a personal reflection of my affective and emotional understanding of the subject. I have always been interested in our shared responses to archival images, our sense of time and our knowledge of historical events. My portraits are spectres, images conjured through art and writing that perhaps can be understood as a romantic appeal for an alternative aesthetic state. I use the photograph as a template: like my archive of literature, they become footnotes.

The lure of Maria Lani was like a fiction and became the inspiration for my show, Into the Thousand Mirrors at Lismore Castle Arts in 2021. We can only grasp a sense of Lani via artworks and statements by the artists for whom she posed. I was fascinated with how Cocteau describes her when he attempts to draw her. He cries: “Every time you take your eyes off her, she changes.” Matisse also records his frustration when attempting to portray her enigmatic features. He exclaims: “What kind of creature are you? There is something between me and you. I cannot find you. God doesn’t want me to.”

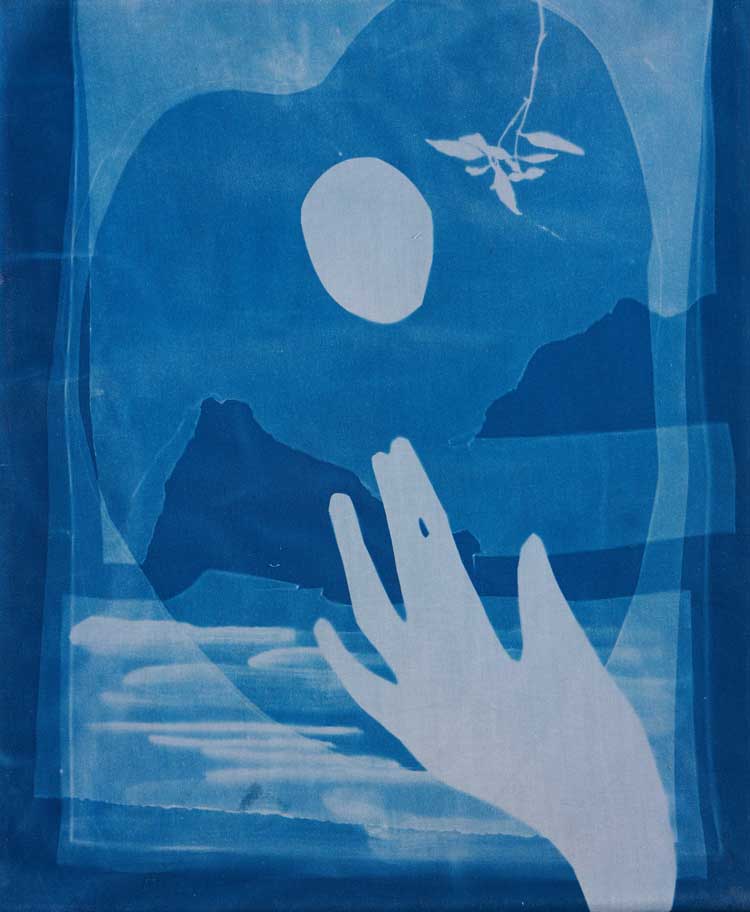

Kaye Donachie, Untitled VIII, 2016. Cyanotype on cotton, 30 x 23 cm. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London. © Kaye Donachie. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

As an actress she was able to remove her personality, she became a mirror that left Cocteau unable to grasp her form. This is a perfect metaphor or analogy for my approach to painting a face. I see it as an armature, a familiar structure that can support descriptive applications and passages of paint and allow figural and abstract gestures to be read simultaneously. I enjoy the visceral qualities of paint and the evocative painterly marks that can facilitate our emotional connections to an image. I see that each portrait is constructed as if in conversation with another. I think of each painting as mirroring the other – as if they are versions with different emotional capacities.

ARC: The exhibition catalogue reminds us that, a few years ago, you painted some compelling groups of figures; what led you to focus not just on individual characters but on closely cropped compositions of one woman?

KD: I have always had a fascination with places and people that exist on the periphery of society. Monte Verità in Ascona, Switzerland, was a perfect haven for creatives and alternative thinkers wanting to escape the horrors of the first world war. The history of this community was a focus in my work, describing landscapes that represented the identity of these alternative communities. When I visited Ascona, I became more inspired by the women within the group. Emmy Hennings’ life was particularly beguiling: she was a successful artist yet defined as the wife of Hugo Ball.

I found the women’s vague biographies compelling and representing a single figure meant relying more on the act of painting to convey ideas. I decided that the single figure could act as a cipher, reflecting affective forces.

Kaye Donachie, Descending into the midst, 2022. Oil on linen, 46 x 36 cm. Private Collection. © Kaye Donachie. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

ARC: Your subjects’ eyes are portrayed obliquely, whether downcast, askance, obscured or even closed. Why do you choose never to have your subjects look us in the eye – is this a means of emphasising their interior lives rather than their relationships with the outside world?

KD: The figure’s gaze is usually averted as it places the figure into a different psychological or contemplative space to that of its viewer. I feel a direct gaze would formalise the painting as portraiture. I do not want the subject to be considered a portrayal of the sitter or model. My concern is wholly with the act of painting. Using figural gestures that have emotional resonance, it imbues images with significance. I resist an over-explanation of the subject and want the compositions to be edited to suggest a fragmented or abstract narrative.

Kaye Donachie, Monotonous Remorse, 2019. Oil on linen. Pallant House Gallery, Chichester (purchased with support of the Contemporary Art Society 2020). Photo: Pallant House Gallery, Chichester. © Kaye Donachie. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

ARC: The other element on show is your own selection of paintings, drawings and prints from the permanent collection at Pallant House, displayed in dialogue with your work Monotonous Remorse. This “chorus” of works, as it is referred to, is placed on a background of wallpaper that you designed, divided into screen-like partitions. What did you have in mind in terms of how you choreographed these works, whether in relation to one another or vis-a-vis your own work?

KD: As an artist, I typically navigate my way through exhibitions by drifting between one object and another. I use an aesthetic interpretation to connect disparate ideas to the present and this allows the historical context to have a relevance and meaning within my own practice. I approached the Pallant House Collection with a similar perspective. My selection of work from the collection was conceived as an assemblage. I chose works that shared a charged intensity, focused by a desire to seize the interior lives of their subjects.

I curated the works with a focus on creating a nuanced personal choreography, with an intention of allowing works to resonate and images to sing. My selection at Pallant House was titled Song for the Last Act: Chorus, the idea of voices in unison, connecting to my solo show within the same venue. My selection could be considered a continuation of my curation of my solo show at Plateau, Frac Île-de-France, Paris, in 2017.

Among my own works, I included historical works by avant garde female artists. The conversations between the works are apparent and visualise inspirational sources instead of academic comparisons. These opportunities are unique as they allow me to share a moment of self-reflection, capturing a certain kind of search into the images and histories I am drawn to.

Kaye Donachie, Come now, be content, 2016. Oil on canvas, 30.5 x 40.6 cm. The Tom and Chai Hall Collection. © Kaye Donachie. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

ARC: Although in some ways very painterly, there is also a cinematic aspect to your work, in terms of those frame-like divisions and especially in the extensive use of closeups and dissolves within the paintings, sometimes with a sense of using film-like special effects, such as when you superimpose a face or figure on to another face. Do you think about film when you’re making your work? Perhaps it is almost impossible not to think about cinema when contending with 20th-century art forms?

KD: I do imagine myself as the director of a short film when I place images together, whether that’s on the studio wall or within an exhibition space.

I return to the work of writers and film-makers such as Marguerite Duras and James Broughton, which I have always found enigmatic and seductive. I have curated their films alongside my own work as a way to connect to their aesthetic knowledge. Both convey loose narratives that are punctuated with images falling in and out of focus and long, drawn-out shots. In their writing and film-making they share a strange ability to make images where one space and time can dissolve into another, through the form of an elliptical poem. My affinity to this kind of film-making is evidenced especially in my cyanotypes, one of which is included in my Pallant House exhibition. The image is made by drawing directly on an illuminated source and is a painterly alchemy for overlaying of figural images and condensing time.

Kaye Donachie, Young moon, 2018. Oil on linen, 50 x 40.5 cm. Silka Rittson-Thomas. © Kaye Donachie. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

The connection to the cinematic and frames of time was important to me when thinking about the curation of Song for the Last Act and Chorus at Pallant House. I wanted the architecture and the wallpaper to act as filmic reels, becoming divisions and screens between images and I like that the idea that the placement of paintings in a space as singular condensed images can operate cinematically.

• Kaye Donachie: Song for the Last Act is at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, until 8 October.