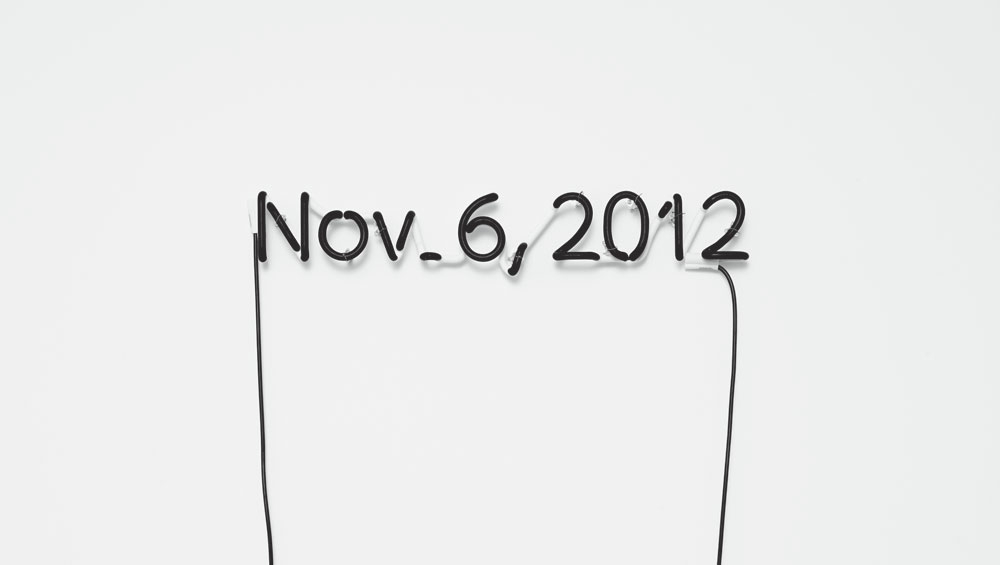

Glenn Ligon. One Black Day, 2012. © Glenn Ligon; Courtesy of the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York, Regen Projects, Los Angeles, and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans

30 September 2017 – 21 January 2018

by ALLIE BISWAS

In 2016, the Joyner/Giuffrida Collection was celebrated through a publication of nearly 400 pages. The book elucidated the collection’s prominence as one of the most significant holdings of modern and contemporary work by African-American and African diaspora artists. Works from the collection are now on display in an exhibition at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, which similarly draws attention to the important developments made by black artists over the past 70 years or so, specifically relating to abstraction.

Norman Lewis. Afternoon, 1969. Oil on canvas, 72 x 88 in (182.9 x 223.5 cm). © Estate of Norman W. Lewis; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY.

The show reflects on a number of interesting notions: the ways in which postwar black artists have constructed their identity through their reliance on abstraction; the formal affinities between artists of different generations; and the role of non-figurative art as both personal expression and political impetus. Aside from these inquiries, though, is a clear intention to rewrite a mainstream art historical narrative that has repeatedly refused to include art made by black American artists. Indeed, the premise of the Joyner/Giuffrida Collection, which was started by San Francisco-based couple Pamela J Joyner and Alfred J Giuffrida in 1999, has been, in effect, to correct how the development of modern and postmodern painting and sculpture in the US has been recorded.

Leonardo Drew. Number 52S, 2015. Wood, 96 x 96 x 14 in (243.9 x 243.9 x 35.6 cm). © Leonardo Drew. Photograph: John Berens.

The exhibition’s title, Solidary & Solitary, is suggestive of a binary that refers to the demands (and restrictions) that black artists have historically been subjected to when considering what it is to be, and create as, a black artist. The Ogden’s display materialises through its acknowledgment of this tension: those who have considered their art as framing their own unique sense of self, and those who have used it for the purposes of forging a collective black identity.

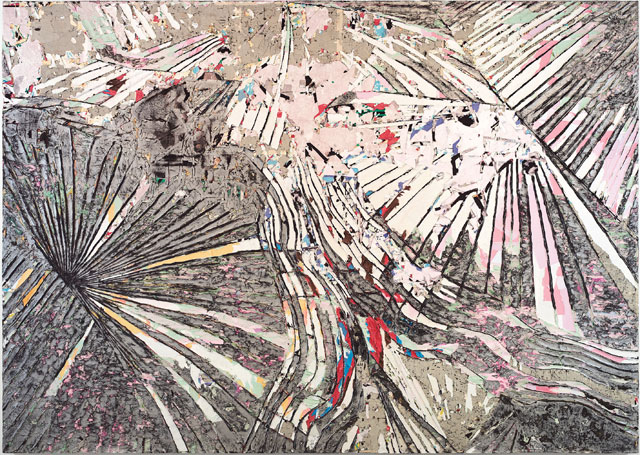

Mark Bradford. No Time to Expand the Sea, 2014. Mixed media on canvas, 8 ft 6 in x 12 ft (259.1 x 365.8 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

The majority of the 14 artists selected for the show have been paired with another artist, presented in a gallery as a “duet”. Otherwise, they have had a room dedicated solely to their work (termed here as a “solo”.) Serge Alain Nitegeka and Tavares Strachan act as bookmarks to the exhibition, their work appearing in other locations of the museum but still closely affiliated.

The curatorial method applied allows for the resonances between artists to be explored, while also allowing in-depth focus on individuals who have either had longer careers (Sam Gilliam, b1933, Charles Gaines, b1944) or whose work has developed in a particularly singular style (Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, b1977).

Sam Gilliam. After Glow, 1972. Acrylic and dye pigments on canvas, 6 ft 2 1/4 in x 8 ft 4 1/4 in x 2 in (188.6 x 254.6 x 5.1 cm). © Sam Gilliam. Courtesy of the artist.

The curators take Norman Lewis (1909-79) as their starting point; he is rightly held up as the most important abstract artist of the earlier period. Lewis went on to be hugely influential on future generations, especially African-American artists who were beginning to establish themselves in the 60s and 70s. The show’s accompanying brochure includes a quote from Jack Whitten – a younger artist, born in 1939, who came up after Lewis, and who appears later on in the exhibition – in which he describes his forebearer as “a gift of cosmic proportions”. The gallery of Lewis’s hazy and vividly coloured paintings features the earliest work in Solidary & Solitary, a scratchy grid of pastel and crayon forms on paper from 1945 called Conversation (Two Abstract Heads).

Kevin Beasley. Bronx Fitted, 2015. New Era® fitted Yankees caps, bandanas, resin, television mount; diameter 70 in (177.8 cm), depth 16 in (40.6 cm). © Courtesy of the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York. Photograph: Jean Vong.

Gilliam, a peer of Whitten’s, has 10 works on view, including Stand, an important draped painting that dates from the early 70s. Gilliam was a critical figure within the colour field school and is recognised for his unique idea of draping a canvas, painting on it as it hung without a stretcher. The display shows Gilliam’s huge range, starting with a canvas of dye pigments from 1972 and ending with a vertical acrylic on birch work from 2010.

Melvin Edwards. Central Ave. LA, 1991. Welded steel, 14 x 11¾ x 9½ in (35.6 x 29.8 x 24.1 cm). © 2017 Melvin Edwards / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The galleries that present a pair of artists articulate compelling associations. The importance of raw materials, such as wood and steel, is evident within the brutal sculptures that comprise the Lynch Fragments series by Melvin Edwards (b1937), which was a response to racial violence faced by African Americans. These dark, spiky objects surround the intrusive sculptural works of Leonardo Drew (b1961), which expand and test their own materiality. Similarly, the coupling of Kevin Beasley (b1985) and Shinique Smith (b1971) reveals artists who are interested in found fabric, but use it in very different ways. Although they both turn to this medium to examine physical properties as well as social functions, Beasley’s sculptural tendencies result in sturdy objects that consist of clothing melded to foam and resin, and Smith’s patterned textiles are precisely shaped into collages.

While several of the works on view depict critical moments in an artist’s career, others seem less representative, and one wonders how the curators made their selections. Given that all the works here come from a private collection, it is likely that the curatorial team were often dealing with the practical issues of first-choice works being on loan elsewhere, for instance. But, for the most part, for the occasion, the selection on display provides substantial enough examples of each artist’s work.

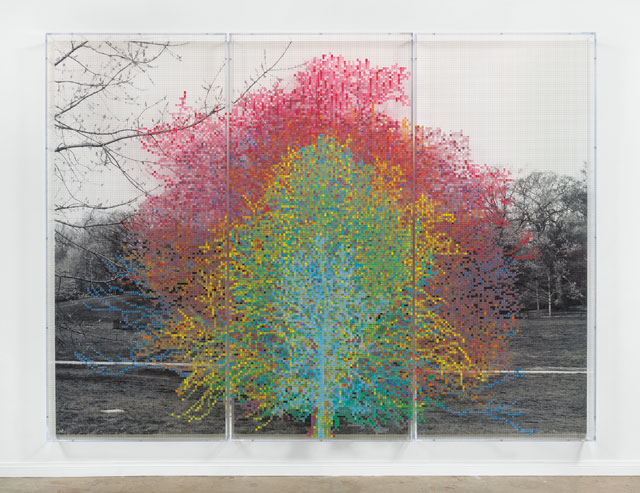

Charles Gaines. Numbers and Trees, Central Park, Series I, Tree #9, 2016. Black-and-white photograph, acrylic on plexiglass (3 panels), each 96 x 42 in (243.9 x 106.7 cm), overall approx. 8 ft x 10 ft 6 in (243.9 x 320 cm). © Charles Gaines. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

As an institution that seeks to piece together a far-reaching history of the American South, and which possesses the largest and most wide-ranging collection of Southern art, the decision to incorporate Solidary & Solitary within its programme might seem puzzling. Other than the flimsy association of birthplace for some of the artists in the show (Gilliam originates from Mississippi; Whitten from Alabama) the exhibition does not seem to readily pertain to the Ogden’s mission. What is valuable to understand in this context, however, is the history of New Orleans; a city that has, historically, depended on the vital influence of its African American citizens in order to create its cultural identity. Today, more than half the city’s population is cited as black or African American, and an area north of the French Quarter, Tremé, is largely discussed as the country’s oldest black neighbourhood.

Sam Gilliam. Stand, 1973. Mixed media on canvas, 7 ft 1½ in x 9 ft 101⁄8 in (217.2 x 300 cm). © Sam Gilliam. Courtesy of the artist.

The interest in Solidary & Solitary from the local residents in New Orleans has been marked, with record-breaking audience figures and an explicit engagement with younger audiences. This is all the more encouraging given that Prospect.4, the citywide triennial of contemporary art that runs in New Orleans until February, may not have yet managed to cultivate this level of enthusiasm from the community.

The Ogden’s exhibition has arrived at a moment in time when the critical contributions made by black artists to the progression of recent and current art practices, particularly in the context of the United States, is being examined. Solidary & Solitary comes in the wake of shows like Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, Black Radical Women: 1965 – 1985 and, most recently, Soul of a Nation.

At this time, Solidary & Solitary will travel to six more venues in North America, including the Baltimore Museum of Art (the exhibition’s co-organiser) and the Pérez Art Museum Miami, as well as museums at the University of Chicago, Duke University and the University of California. The emphasis on educational institutions is not incidental – for an exhibition that seeks to assert new perspectives on the evolution of art history, it is essential that a new generation of students are confronted with an exhibition such as Solidary & Solitary.