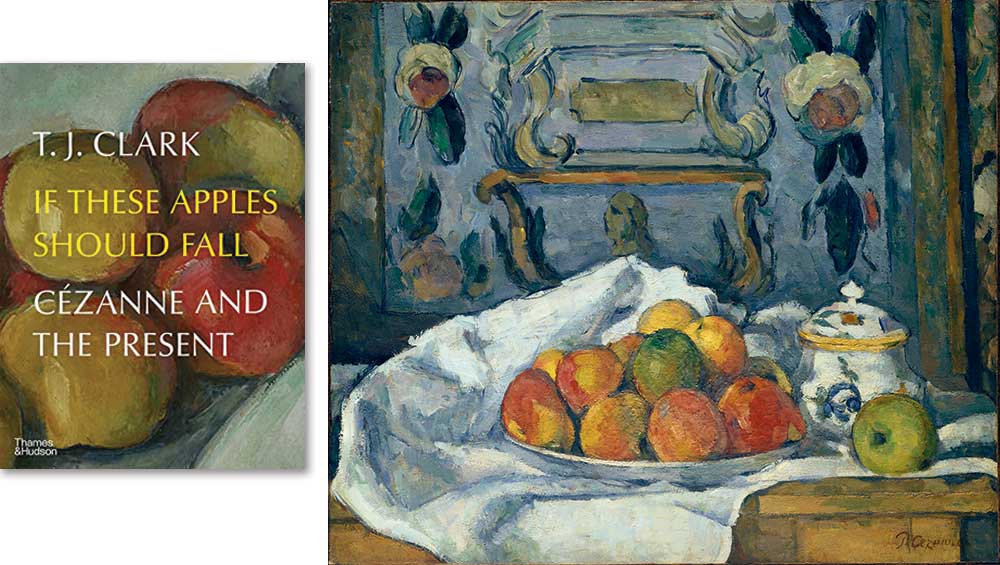

Left: If These Apples Should Fall: Cézanne and the Present by TJ Clark. Right: Paul Cézanne. Dish of Apples, c1876-77. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Reviewed by NICOLA HOMER

“With an apple I will astonish Paris,” said Paul Cézanne (1839-1906). This line appears high on a wall of the EY Exhibition: Cézanne at Tate Modern. The vignette captures the brilliance of the French painter, who arrived in Paris in 1861, when he met the Danish-French impressionist Camille Pissarro at the Académie Suisse. Cézanne spent 30 years on the subject of “what it meant to be a modern painter”, according to the Tate exhibition’s introduction. Quite a feat given the academic tradition of neoclassical painting in France in his time.

At a crossroads in art history, Cézanne participated in the first impressionist exhibition in 1874. His first solo show, with Ambroise Vollard in Paris in 1895, marked a transition for the artist as he cultivated a unique modern style. “The Louvre is the book from which we learn to read. However, we should not be content with holding on to the beautiful formulas of our illustrious predecessors,” he is quoted as saying in 1905 in the Tate Modern exhibition. Cézanne captured the attention of the British art critic and painter Roger Fry. Together with artworks of Gauguin and Van Gogh, his work featured in Manet and the Post-Impressionists, the show organised by Fry at London’s Grafton Galleries in 1910. The modernist writer Virginia Woolf gives a flavour of the importance of the show: “In or about December 1910, human character changed.”1 The colour of his landscapes and still lifes adds up to being a tonic at the Tate exhibition. The effect is tangible in the lively conversation there. The accompanying catalogue perfectly sums up why Cézanne’s art matters for people: “Cézanne’s revolution lay not so much in what he painted, but in how he painted, by which we mean not just a process of applying medium to substrate, or formalist invention, but the way he transcribed his experience of looking at the world for others to share.”2

Paul Cézanne. House near Gardanne, c1886-90. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The scene is set. Enter Professor TJ Clark. The widely respected art historian has written his latest book on the painter, entitled If These Apples Should Fall: Cézanne and the Present (2022). The publication was a long time in the making; all the chapters began as lectures. The professor taught art history at Harvard and the University of California, Berkeley. In the book, he draws inspiration from a distant memory of looking at a copy of one of Cézanne’s paintings, The Basket of Apples, on the dust jacket of a book by the American art historian Meyer Schapiro, a volume in the Library of Great Painters. He offers a respectful appraisal of his subject’s oeuvre from the outset: “The book that follows gathers together efforts, made over decades, to come to terms with the strangeness as well as the beauty of Cézanne’s achievement.”

Paul Cézanne. The House with Cracked Walls, c1892-95. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The book marks a fresh departure as the scholar turns to poetry in the introduction, for example in Tulips in a Vase, which describes the inspiration that he derived from the French master Eugéne Delacroix. This echoes a story charting how Cézanne grew up in a place where the academic teaching of art cultivated a sense of liberty in Schapiro’s writing. Indeed, Cézanne’s early works drew on paintings of Delacroix and Poussin, and novels of Flaubert and Zola. Yet his interest in impressionism, the antithesis of academic painting, and his friendship with Pissarro would be a decisive influence on his later works. The effect of his landscape painting is beautifully described by Clark in Hillside in Provence, inspired by a visit to the French 19th-century room at London’s National Gallery: “How this other world takes place in us, and why we fear it, / Is Cézanne’s subject. / Maybe the ivory road (or is it a riverbed?) in the foreground of Hillside / in Provence / Is intended to spell this out. It is the floor of the earth / Emerging after the flood, with colours stacked in a small, neat pile to one side, / as if / Waiting to be used.”

Paul Cézanne. Ginger Jar, c1895. Barnes Foundation, Philadeplhia. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Photo Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Philippe Mageat © Succession H. Matisse/DACS 2022.

Poetry serves as an elegant framing device for a book that arrives at the defining moment of the early 20th century, the great war. The selection of The Waste Land by TS Eliot, who presented views that were classicist in literature, fits the narrative of a modern painter, born in Aix-En-Provence in southern France. For the artist’s crowning achievement, a series of works based on a monumental mountain, the Montagne Sainte-Victoire, stood for a particular sense of history; the south was associated with a new classicism. In chapter three, Cézanne and the Outside World, Clark’s style crisply captures the beauty of his landscapes, for example when he turns to the canvas Montagne Sainte-Victoire seen from Chateau Noir (c1900-04) to say: “The mountain looks crystalline, made of a substance not quite opaque, not quite diaphanous; natural, obviously, but having many of the characteristics – the crumpled look, the piecemeal unevenness – of an object put together by hand.”

After this introduction featuring poetry, the book is organised into five chapters, which educate the reader about Cézanne’s apprenticeship with Pissarro, his treatment of everyday objects in the form of the still life, his unique approach to landscape painting, his Card Players and a painting by Matisse, about whom Clark writes: “His Garden at Issy was painted in a Paris suburb in 1917, at a time of war and revolution … The exchanges of fire at the front to the north could sometimes be heard in Matisse’s studio.” In the first chapter, Clark delineates the importance of Cézanne’s working friendship with Pissarro in the early 1870, by unpacking the characterisation of the artist as “humble and colossal” and looking at how this signposted the way forward for French painting. As Schapiro noted in his text: “He was more than a teacher and friend to Cézanne; he was a second father. Cézanne spoke of him with veneration – 30 years afterwards he called him ‘the humble and colossal Pissarro’.”3 Indeed, the apparent role of Pissarro as a mentor to Cézanne, who shaped his perception of nature, can be seen in the comparison between the pair of artists and Plato and Socrates, between French painting and Greek philosophy in the book’s first chapter, entitled Pissarro and Cézanne. Clark writes: “The coming together of Cézanne and Pissarro – their common cause, their peaceful coexistence, their rivalry, their contrariety – is a mystery. For me it is the deepest mystery of the 19th century; and I cannot escape the feeling that if we could unravel it we would have in our hands the key to French painting, in much the same way as the relation of Plato to Socrates, for example, still seems the key to the enigma called ‘philosophy’.” One strength of this book is encapsulated here: the use of comparison as a discursive strategy.

Paul Cézanne. Plaster Cupid, c1894-95. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. Rodchenko Stepanova Archive, Moscow. © Rodchenko & Stepanova Archive.

Clark is spot on when he says comparisons of paintings have been “the staple of art writing for a century” as students of the discipline of art history can tell you. The New York Museum of Modern Art’s 2005 exhibition Pioneering Modern Painting: Cézanne and Pissarro 1865-1885 is a case in point, leading to an analysis of pairs of paintings. The author illustrates how Cézanne drew inspiration from Pissarro’s direct observation of nature with their two Louveciennes paintings. He is great at close looking here and elsewhere. In chapter two, Cézanne’s Material, the fruits of this approach appear in the focus on the richly coloured painting Still Life with Apples (c1893-95) from the J Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles: he describes the array of objects as “composed and crystalline”. In the next chapter, Cézanne and the Outside World, there is a thoughtful passage on Trees and Houses (c1885–86) from the collection of the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris: “Look at the triangle of sunlit wall between the eaves and the branch.” The clear and crisp style enhances the appreciation of the brightly coloured work.

Paul Cézanne. The Bay of L’Estaque, c1880-82. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Another strength of this book is seen in the author’s ability to appraise established readings of Cézanne’s oeuvre. The publication critiques writings on the painter, from the essays of Clement Greenberg to the philosophy of Maurice Merleau-Ponty. The professor highlights two excellent texts on Cézanne, including those of Roger Fry and Meyer Schapiro, noted for their “plain style” in the second chapter. In chapter three, Clark presents some great historical context, for example a 1910 piece by Fry, describing The Bay of L’Estaque (c1880-82), which neatly captures the aesthetic value of his artwork in philosophical terms. Clark writes: “‘In a picture like L’Estaque’ – here is Roger Fry in 1910, discussing a painting now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art – ‘it is difficult to know whether one admires more the imaginative grasp which has built so clearly for the answering mind the splendid structure of the bay, or the intellectualised sensual power which has given to the shimmering atmosphere so definite a value.’” Yet while Clark shows admiration for Fry’s writing, for example on “the architectural plan” and “colour harmonies” of Cézanne’s composition in a 1910 piece, he appears to question the latter’s positive terms of value, and suggests a list of “implied contingent negatives” adds to the strength of Cézanne’s painting Trees and Houses. This offers a new layer of understanding to the work.

Paul Cézanne. The Card Players, c1890-92. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

It is delightful to see that he introduces a new lexicon for the artist’s work, for example in the description of the “fulcrum" of the effect of the Getty’s Still Life in chapter two – a word that also describes the Card Players in chapter four, entitled Peasants – which is distinct from the “punctum”, used by the French philosopher Roland Barthes on photography. “What I see are the apples,” says Clark. “And maybe they strike me as the picture’s fulcrum because they and the edge of the blue material are so much an image – an epitome – of containment, of firm holding, two shapes nicely settled. Cézanne has worked hard at nesting the apples in place.”

One abiding impression is that the author signposts “a social view” of the painter’s work, as seen where he highlights the fact that the Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke produced a letter on a train in 1907, after seeing the Getty Still Life in Prague, describing the material’s colour as a “bourgeois blue-cotton blue”, symbolising “the belonging of Cézanne’s material to a specific class world”. This reveals the comfort of the life of an artist who had family support to keep going with his work. Clark explores the relevance of writings of the German philosopher Karl Marx in connection with the painting, lending an appreciation of the value of commodities to understanding his oeuvre. On a positive note, his encyclopaedic knowledge of literature emerges, including writings of Dante, Shakespeare and Keats. The author offers a rare historical insight as he looks at humorous writing by the Irish playwright Samuel Beckett and adapts his words in a fresh turn of phrase: “still-life-icality”.

Paul Cézanne. Boy with a Skull, c1896-98. Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia.

Overall, this sums things up nicely, as the discussion of the radical subjectivity of the playwright shows how the way in which Cézanne captured his perception of the world with his presentation of space and his modern style of painting, in his use of colour and light, broke radically with academic tradition. The monograph explores this originality of thinking, paving the way for the development of 20th century modern art movements, as the work of Cézanne inspired both Picasso and Matisse, the subject of the final chapter, Matisse in the Garden, which is an interesting addition to the book as it captures a specific sense of history associated with the first world war. The conclusion paints history with a broad brush, providing an elegant counterpoint to Cézanne in the Dutch master Jacob van Ruisdael. This book is a difficult but worthwhile read: a masterclass in art history.

References

1. Virginia Woolf in Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown, 1924. In: Modernism: An Anthology of Sources and Documents, edited by Vassiliki Kolocotroni, Jane A Goldman and Olga Taxidou, published by Edinburgh University Press, 1998, page 396.

2. Organized Chaos: Looking at Cezanne. In: Cezanne, edited by Achim Borchardt-Hume, Gloria Groom, Caitlin Haskell and Natalia Sidlina, published by the Art Institute of Chicago, 2022, page 18.

3. Paul Cézanne: The Library of Great Painters by Meyer Schapiro, published by Harry N Abrams, Inc, 1952, page 26.

• If These Apples Should Fall: Cézanne and the Present by TJ Clark is published by Thames & Hudson, price £30.