Hélio Oiticica, Agrippina is Rome-Manhattan, 1972. Super 8 film on monitor, 15 min 5 sec. Courtesy of César and Claudio Oiticica.

De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea

23 September 2023 – 14 January 2024

by JOE LLOYD

In 1970, the Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica (1937–80) was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. He would move to New York for two years, participate in a survey exhibition of conceptualism at the Museum of Modern Art and work at securing funding for a big outdoor installation in Central Park. It offered an opportunity to escape a country sunk into repressive, US-backed military dictatorship. But it also opened up a wild new frontier in his already revered career.

Oiticica had made his name through the preceding decade and a half. First, as a leading light among his country’s abstract painters, specialising in works with a warm citric palette. At the end of the 1950s he joined the Neo-Concrete Movement, which sought to escape the confines of regular painting. He produced small monochromes on wooden plaques that aimed to express, rather than simply represent, light and colour.

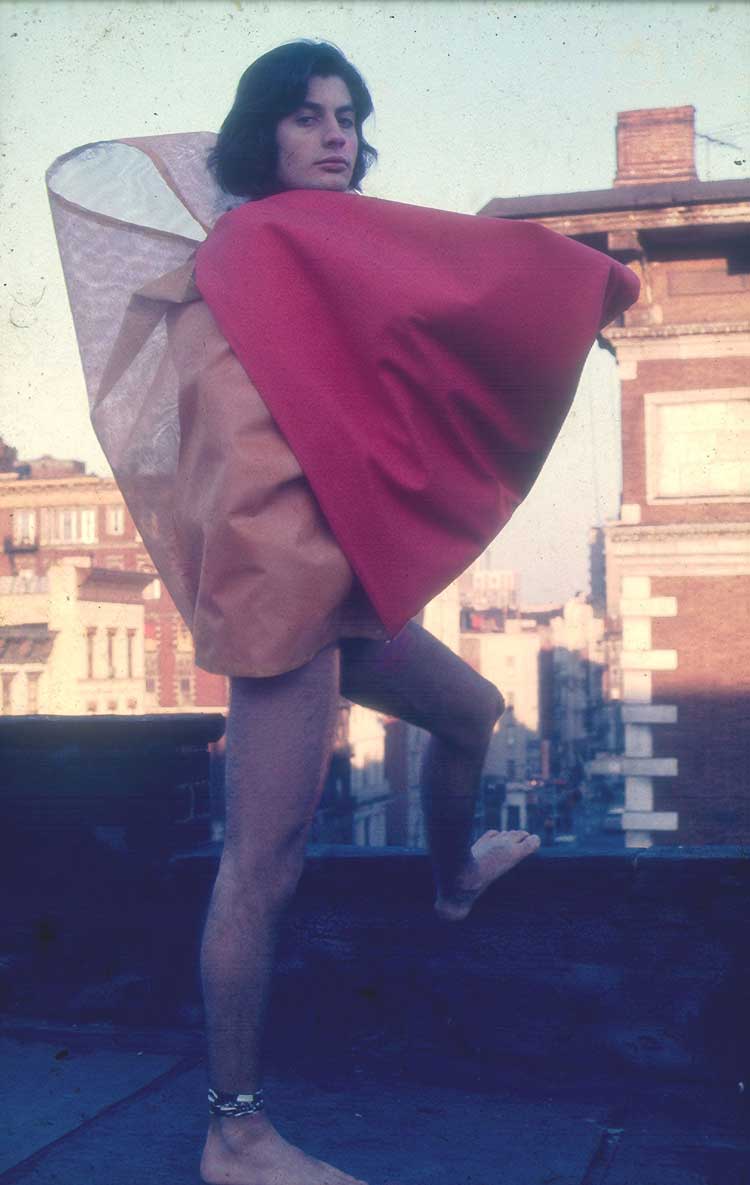

Hélio Oiticica, Parangolés, 1964-79. Acrylic on canvas, fabric, nylon, rope and plastic, dimensions variable. Installation view, Hélio Oiticica: Waiting for the internal sun, De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea, 23 September 2023 – 14 January 2024. Photo: Rob Harris.

Thus began a compulsive tug towards conceptual art. Throughout the 1960s Oiticica produced interactive sculptures. These included the Parangóles (1964-79), wearable sculptures in the form of capes. There were objects that audiences could manipulate (Fireballs) and large-scale room-like structures (Penetrables) that they could step into and interact with others. His 1967 opus Tropicália (1966-67), owned by the Tate, features two such units, a floor of sand and gravel, pot plants and two caged parrots. A critique of the military regime’s attempt to reduce Brazilian culture to exotic stereotypes, it gave its name to the Tropicalismo movement of radical Brazilian music, and presaged the rise of the installation as an artistic medium.

A new exhibition at the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill-on-Sea captures this febrile period. It features two of his large-scale installations, Projeto Filtro – For Vergara (1972) and CC5 Hendrix war/Cosmococa — Programa-in-Progress (1973); a collection of Parangóles, which visitors are encouraged to wear; a selection of rarely seen video and slide works; and a biographic wall illustrated with well-chosen archival photography. It is a concise selection, but it captures the breadth of Oiticica’s achievement, and, perhaps most importantly, the excitement that his participatory works generated.

Hélio Oiticica and Neville D’Almeida, Cosmococa/CC5 Hendrix War, 1973. Installation view, Hélio Oiticica: Waiting for the internal sun, De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea, 23 September 2023 – 14 January 2024. Photo: Rob Harris.

In 1969, while preparing for an exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, Oiticica formulated the concept of Creleisure — a portmanteau of “creation” and “leisure” that also played on creer, the Portuguese word for believe. This idea suggested that leisure was essential for creativity and posited a fusion of art and life that would claw back time from capitalism. As Oiticica wrote: “Like the experience of pleasure or not knowing when it's time to relax and be lazy, not occupying a specific place in space or in time is or could be a 'creative' activity.”

While the earliest Parangóles predate this formulation, they epitomise the idea that creativity should go hand-in-hand with leisure. They were inspired by costumes from carnival, one of the ultimate expressions of collective celebration. Oiticica would take them to favelas (Brazilian shanty towns) for happenings involving samba music and dancing, which he lionised for its free expression and unintellectual inhibition. But when he asked friends from a favela to perform with the Parangóles at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro, the museum director refused to let them enter. Later, he would roam the New York subway and encourage commuters to wear them.

Hélio Oiticica, P32 Parangolé‚ Cover 25, New York, 1972. Courtesy of César and Claudio Oiticica.

The capes vary immensely. One has the phrase “estou possuído” (I’m possessed) written on it in childlike red letters and what appears to be a sack of straw attached to it; another displays a picture of a classic grey alien. Recreated after a 2009 fire that destroyed a significant tranche of Oiticica’s works, they now feel almost too precious to touch. But it is interaction that completes them, turning them and their wearers into moving sculptures. For Oiticica, the artefacts came secondary to the concepts and interventions — an idea that placed him in firm opposition to the commercial art world, with its demand for paintings and objects that can be sold and collected.

Projeto Filtro - For Vergara is an enormous penetrable. It is a labyrinth — or more accurately a zigzagging path through an enclosed cuboid — divided into a series of rooms by curtains. Several of the rooms feature speakers, some playing local radio, others readings by writers Gertrude Stein and Haroldo de Campos. One features a TV playing news, another a functioning orange juice machine (Rio is famed for its juice bars). The wall of the structure that faces the De La Warr’s windows is lined with translucent coloured panels, which add a surreal tint to the pavilion’s spectacular views over the English Channel.

Hélio Oiticica, Penetrável Filtro, 1972. Mixed-media installation, Installation view, Galerie Lelong, New York, 2012. Courtesy of César and Claudio Oiticica.

Oiticica intended this work as a damning portrait of his native land, lost in a maze of mass media voices, kitschy exoticism and easy pleasures, unable to see the world for what it really is. He called it a “game-joke-labyrinth-noise-sound-recorder transistor buzzer blender tv” parodying “the myth of work and of kitsch… that contaminates Brazilian minds.” Today, it seems a little sedate when matched up to this description. And the use of high literary readings would seem to encourage the sort of intellectualism that Oiticica set himself against. But it creates a striking atmosphere of disorientation and instils the sense that one is trapped within a constant stream of information overload. One wonders what Oiticica would have made of today’s media overload.

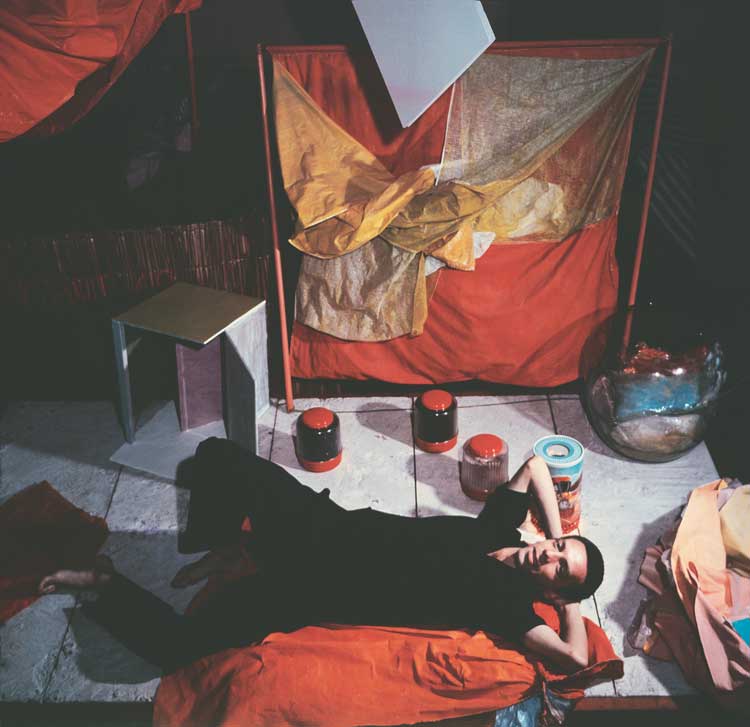

It is the other installation in the show, however, that broke new ground for both Oiticica and contemporary art. The Cosmococa series, created in collaboration with fellow artist Neville d’Almeida, are environments created with 360° video projections. They are alleged to have begun when the two observed cocaine powder on a Frank Zappa record. They then decided to use the drug as a sort of pigment, making marks over various cultural figures. Cocaine became a symbol for US imperialism over South America, a sign of corruption, but also a transgressive thumb at societal structures.

Hélio Oiticica’s Super 8 works Wall Street New York (1971), Agrippina is Rome-Manhattan (1972), and Gay Pride Parade (1971). Installation view, Hélio Oiticica: Waiting for the internal sun, De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea, 23 September 2023 – 14 January 2024. Photo: Rob Harris.

The pair was inspired by the filmmaker Jack Smith’s happenings and non-narrative works. Oiticica had begun making Super 8 films. The selection shown in Bexhill shows his roving eye capturing the buildings of Wall Street, the drab conditions inside an office and, reflecting his embrace of the city’s queer scene, the both exhausted and exhilarated aftermath of a Pride parade. He was also interested in slides: Neyrótika (1973) collects images of largely topless men lounging in one of his installations.

Nine Cosmococas were conceived, five of them with d’Almeida. One features a John Cage record and a pool for visitors to bathe in. The work on display here, Cosmococa/CC5 Hendrix War (1973), takes the posthumous Jimi Hendrix compilation War Heroes as its core image. Four walls and a ceiling are projected on to with images of Hendrix’s face covered in cocaine markings, whether mask-like patterns, crosses or a single dab. The album plays loudly, blasting squalls of psychedelic guitar through the valley. Visitors are encouraged to loll around on thickly-woven hammocks, their comfort providing a disconcerting contrast to the sound and images.

Hélio Oiticica with Bólides and Parangolés at his atelier at Engenheiro Alfredo Duarte Street, Rio de Janeiro, 1965. Photo: Claudio Oiticica. Courtesy of César and Claudio Oiticica.

Unable to show these drug-smeared works in galleries, they were only ever seen by visitors to Oiticica’s loft, both friends and men that he picked from the street. After his fellowship ended, Oiticica stayed in New York for almost a decade. His finances dwindled, and he turned for a time to drug dealing. After a near miss with the FBI in 1978, he returned to Rio de Janeiro where he resumed creating the Penetrables. But likely due to the indulgences of his American sojourn, he suffered from hypertension and died of a stroke two years later aged 42. He left behind such an abundance of trailblazing works and ideas that we are still digesting them, almost half a century later.