Tate Liverpool

13 December 2019 – 15 March 2020

by JOE LLOYD

In 2005, Hurricane Stan raged over the Caribbean. Flash foods followed across six countries in Central America, with Guatemala the worst affected. Several hundred lives were lost and entire settlements were destroyed. The Swiss-Argentine artist Vivian Suter (b1949), who, since 1982, has dwelt on a former coffee plantation on the shores of Lake Atitlán, in Guatemala’s southern highlands, saw her rainforest studio flooded. Dozens of works were destroyed. Initially distraught, Suter had something of an epiphany. After painting from nature for much her of career, she determined to work with it. She began laying canvasses beneath her papaya, avocado and mango trees, letting the rain, the earth and plant matter mingle with her paint.

Few places seem so estranged from the natural world as Liverpool’s docks, a brick-and-stone testament to the endeavour of commerce, where even the Mersey has been repurposed as infrastructure. Stepping into Suter’s exhibition at Tate Liverpool, however, a reconciliation with nature suddenly seems possible. Her instinctive, surprisingly flinty paintings are largely hung from ropes attached to the ceiling. They are painted in oil, often lightly washed, on boardless sheets of canvas. These are thick enough to insist on their materiality, but thin enough to be translucent. Their vibrant facades are thus backed by ghostly, faded echoes, as if they capture experiences slipping from immediate memory. Some have bits of twigs caught in them, or wrinkles that might have been caused by spattering raindrops. I hear a mild breeze and faint birdsong, and smell the scent of leaf litter. I can’t tell if these sensations are real or imagined.

[image3]

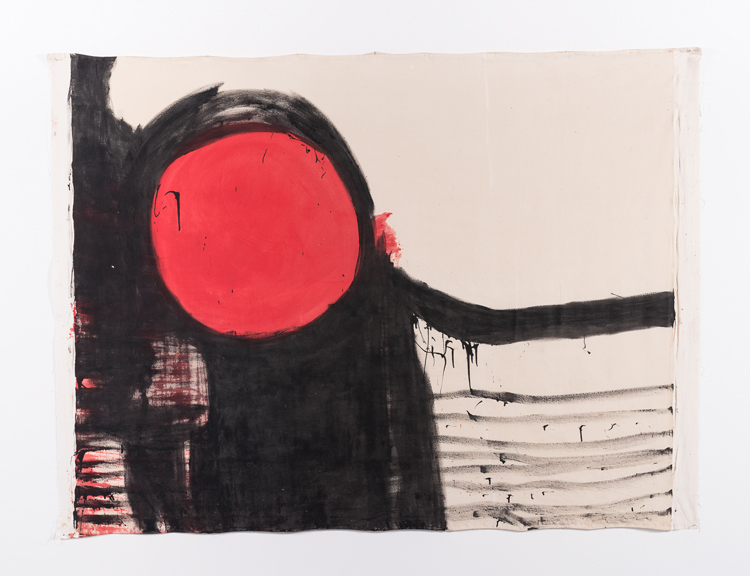

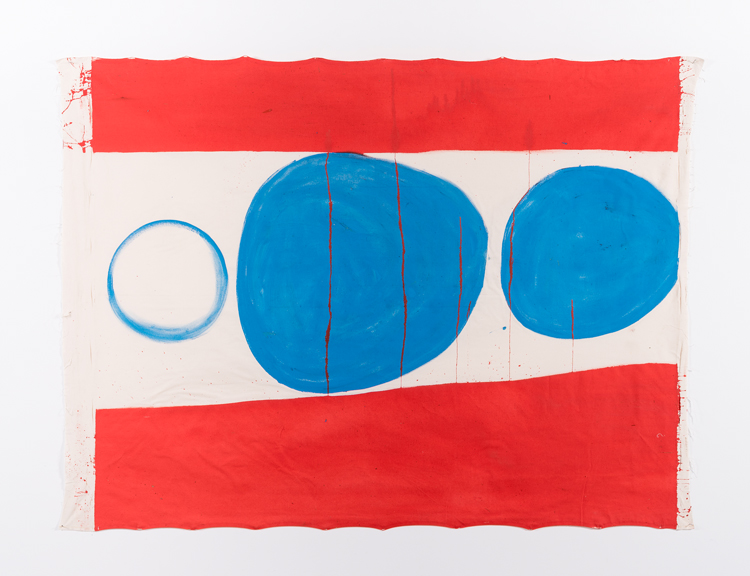

Suter’s images seem to exist somewhere between the representation of nature itself and the representations of her recollections of it. Although a few are figurative – notably here, a blue bird squatting on a branch, which seems to serve as a greeter to the exhibition – the majority are abstract, or abstracted enough that it is difficult to identity their definite form. Certain motifs recur, such as striped vertical lines with exclamation point-like termini, round red spheres on a field of green, and sets of dancing organic protuberances.

The Tate exhibition consists of a single work, albeit one that comprises 53 individual paintings. Nisyros (Vivian’s Bed) (2016-17) was first displayed in Documenta 14 at Kassel. It followed Suter’s 2016 visit to the titular Greek island, and a smaller set of works on canvas, dubbed simply Nisyros (2016), which was installed on Documenta’s Athens foray. In Kassel, Nisyros (Vivian’s Bed) occupied a glass-walled pavilion alongside a characteristically drab road, where the component pieces seemed to skirt the sides of a central space.

[image4]

In Liverpool, cut-off from the city outside, they loop and spiral around, suggesting a succession of unevenly sized rooms. The arrangement can be tricksy. Some of Suter’s most painterly works are almost entirely hidden: a heavily worked, sun-kissed colour field, for instance, hides behind an insubstantial, vaguely biomorphic work in blue. You can see the former only from the side, its radiance dulled by the shadow of the piece covering it. But then Suter’s individual paintings, or at least those collected here, seldom seem to present themselves for scrutiny; their effect comes from the whole.

Suter has a way of arresting expectations, in art and in life. She was born in Buenos Aires to an Austrian mother who had fled Nazi persecution. In the early 1960s, her family resettled in Basel after Juan Péron’s fascist-inflected Justicialist party decided to nationalise business. When Suter began to practice in the early 70s, she specialised in densely worked abstractions of the natural world, painted on unconventionally shaped paper. Her potential break came in 1981, when she featured in a group show at the Kunsthalle Basel.

[image5]

Displeased by the socialising and networking that even then made up the art world’s never-ending round dance, Suter flew to Los Angeles, before embarking on a solitary road trip around Mesoamerican ruins. When she reached Panajachel, a small town on Lake Atitlán, she decided to stay. Joined in the mid-1990s by her mother, fellow artist Elisabeth Wild, Suter continued to paint. But beyond very occasional gallery showings back in Switzerland, she remained virtually unknown for almost three decades.

Things changed in 2011, when the curator Adam Szymczyk, as director of the Kunsthalle Basel, convened a sequel to the 1981 exhibition, featuring the same roster of artists. He then gave Suter a solo show, exhibited her at Museo Tamayo in Mexico City, and placed her (as well as Wild, and Rosalind Nashashibi’s Turner Prize-nominated Vivian’s Garden, a documentary charting the lives of the mother and daughter in Panajachel) in Documenta 14. Since then, she has shot from obscurity to semi-ubiquity, with several exhibitions and commissions around the globe each year. This Tate presentation is her first show in Britain, but, in 2020, it will be followed by a new work at the Camden Arts Centre and an Art on the Underground commission. Later in the year, she will be the subject of a full retrospective at Madrid’s Reina Sofia.

[image6]

Laying the excitement of her life aside, Suter’s not-so-slight return taps into some present-day concerns: humanity’s relationship with its natural environment, a link between art’s centre to its perceived margins, and the craft-like authenticity of her process-based practice, which revels in canvas’ material qualities. But on the evidence of Nisyros (Vivian’s Bed), all this earthiness is overlaid with a more inward bent. Concealed in a dense thicket of paintings is the titular bed itself, draped in the exhibition’s pinkest, most fleshy painting. Another two paintings, dominated by canary yellow, serve as if rugs beneath, while a trio of waterside views hang above like a canopy, or a window.

Once you have happened upon this installation, Suter’s entire exhibition seems to orient itself around it. Is Nisyros’s sensorial depiction of natural world instead the product of dream, of daytime experience blurred and distorted by human imaginings? Is it rooted in place – whether Panajachel, the island of Nisyros, or elsewhere – or adrift in the half-remembered recollections of the artist herself? Perhaps this is why Suter’s paintings rarely seem to touch the ground that once caressed them, but instead float in the air like dreamcatchers, pleasant, pungent and ultimately impenetrable.