Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery, London

25 March – 11 September 2022

by VERONICA SIMPSON

It is a rare treat to see the same show in a different location within the space of a few weeks. Rana Begum’s (b1977, Bangladesh) show Dappled Light has just arrived at Pitzhanger Manor, a Georgian building designed as his country home by Sir John Soane, whose genius with light and colour has rarely been surpassed in architecture.

[image1]

What a conversation Begum’s delicious interventions spark in this space. However, they also looked pretty good in the Mead Gallery at the University of Warwick, where I saw them in early March. There, at what was the grand reopening show for this leading Midlands gallery – its exhibition spaces transformed after a three-year refurbishment – Begum’s exuberant work was perfect for its new white, muscular, contemporary ground floor rooms, all clean geometries and top light. Begum’s distinctive palette, ranging from pop-art neons to sorbet pastels, positively fizzed, and the expert curation highlighted the playfulness and the skill of her material explorations.

At Pitzhanger Manor, though, what added richness arrives with the addition of Soane’s sumptuous, organic curves, his slices of strategic stained glass – and of course his sculptural use of daylight, direct, indirect and reflected.

[image2]

The first work we see at Pitzhanger is the dense, yet gossamer-like cloud of Begum’s steel-mesh sculptures, No 1081 Mesh (2021). At Warwick, these were scattered in drifts across the ceiling - as if a generous, giant hand had just thrown a handful of huge blossoms into the air - and the Mead’s flattened, indirect light brought out the pinks, oranges and silvers of their powder-coated forms. Here, hung below an original, circular Soane skylight laced with yellow glass, they form a more complex, gorgeous mass, with just a single stray yellow cloud set slightly apart to trigger a tonal duet with the glass above. The layering of different coloured puffs inside each cloud form is more apparent here, the mesh textures richer. And how they frame the views, every which way you look: flirting from behind the entrance into the gallery itself; layered against the skylight, or drifting towards the distant park framed by the glazed, far doorway

[image3]

Pitzhanger Manor is a dual experience: the entrance lodge now elegantly extended into a two-storey gallery space (albeit one enhanced by the aforementioned luscious Soane skylights) with one big room and a neater room tucked behind it; then, down an outdoor covered colonnade, the main house draws you through a dark entrance tunnel to arrive at a staircase experienced as a fissure of light, daylight cascading down its steps, bouncing off alcoves, statuary, and clever faux-marble painted walls. The contrast could hardly be greater.

[image9]

Begum has chosen well in responding to the buildings’ different atmospheres: she has draped brightly coloured fishing nets across these manor house stairs, forming an enticing interplay of veiled colours whose layers shift, obscure and reveal as you ascend each flight of steps, almost like a kaleidoscope. At Mead, they were playful wisps of colour, floating against a solid white form. Here, they evoke something perhaps even more ethereal, conjuring both large, richly hued cobwebs and the spreading rays of tinted light that Soane’s stained-glass elements throw on to the floor when penetrated by the sun. Yet what is always joyous about Begum’s work is the everyday, workmanlike materials she uses (these net pieces comprise industrial netting, inspired by the fishermen she observed during a residency at Tate St Ives in 2018) and the fact that these humble elements, transformed by her hands and fine-tuned chromatic sensibility, spark scintillating echoes in even the most opulent settings, such as this stately country retreat.

[image8]

A “cityscape” of columns which Begum has clad in reflective plastic tiles – a classic Begum material, whose fantastic plastic potential she spotted on a previous residency in Bangkok – of white, orange, red, yellow, grey and green, are set up in Soane’s first-floor conservatory. These tall, slim towers converse with the adjacent multitude of Georgian window frames overlooking Walpole Park, setting off a symphony of geometric and chromatic interactions as the sun traverses the room, and riffing off the dazzling blue and yellow shadows that are triggered when afternoon sun hits the strips of stained-glass diamonds Soane had set into the window frames.

The beauty of it is that none of these works was designed for this space. The Mead Gallery was the original destination, and most of the work was made before the call came to exhibit at Pitzhanger. How did Begum feel about this opportunity to showcase her work in the home of the acknowledged master of light, colour and form? “I was really nervous whether that would come through – that sensitivity. I want it to work in harmony with what Soane was trying to do with light and show an appreciation,” she says at the preview. Now, how does she feel? “Delighted.”

[image13]

There was a sense at the Mead of the work choreographing your eye and body, drawing you around the space. Here, the works seem to dance with the buildings. Particularly striking is a huge, eye-popping spray-painted canvas – No 1079 Painting Large (2022) – whose pointillistic presence across from the Mead’s wide, top-lit entrance seemed like rainbow dazzle through spring sunshine. Here, set into Pitzhanger’s smaller gallery, and lit by a geometric, stained-glass skylight, the tones are warmer, richer – more like diving headlong into a dense field of summer flowers.

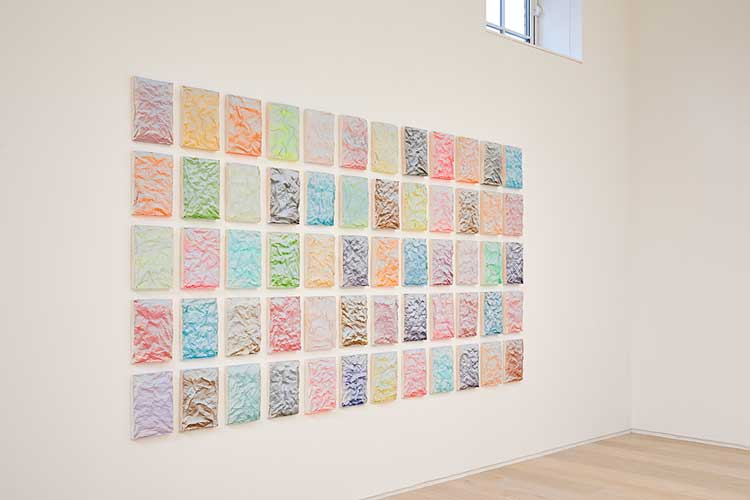

An arrangement of Jesmonite works have an extra layer of iridescence here. Formed from imprints of crumpled paper, their contours – echoing the crinkled balls of steel mesh nearby – positively vibrate as you stroll towards them; it is like a portal into another chromatic dimension. Discussing how different all the works feel here, Begum agrees: “It just does something different in each space. It takes a new form depending on where it is. I almost feel like (each work) has its own mood and own life.”

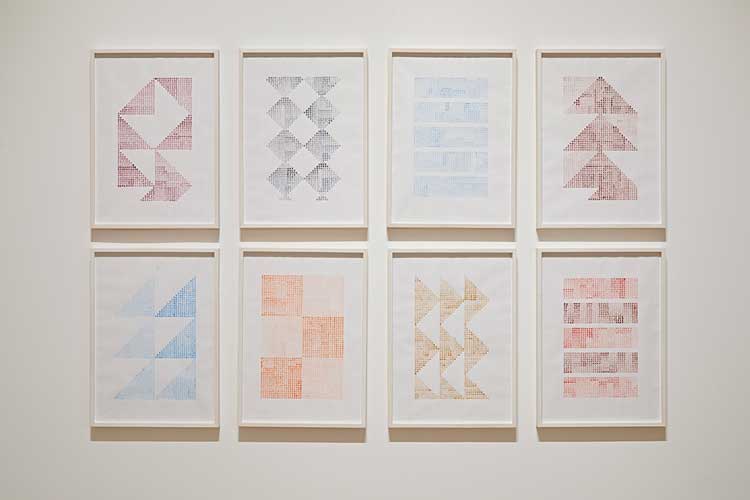

What is apparent to all is that the work here represents an exciting shift, from the harder, mostly-two dimensional and geometric works Begum exhibited at the Parasol Unit in her solo show of 2016, with a more organic, softer, expressive quality. She says: “That’s a new thing, the organic aspect. I was really nervous about it, and I am still mulling it through in my head. I’ve been interested in landscape and all the different facets of landscape. I was recently in California, in Palm Springs: just seeing the landscape there and then coming back to this English body of work was quite intense, seeing the light shift.”

[image10]

Speaking of landscape, there is a new video work – No 1080 Forest (2021) – created for this show, screened in the wonderfully spooky Monk’s Dining Room in the Manor house, the screen surrounded by plaster copies of decorative busts and gargoyles. The film celebrates a far more subtle interplay of colour and form: inspired by the view through a large window in Begum’s new house (created for her by architect Peter Culley), it is a slow-motion depiction of one scene across 365 days, during the intense lockdown year of 2021. The view isn’t particularly picturesque – a few tree trunks, skeins of ropey, dead ivy vines, some gravestones from the adjacent graveyard visible in the distance. With an SLR camera set up, Begum timed a photo to be taken once an hour every hour, then edited out the night-time shots to create this 38-minute meditation on time and the seasons passing. The window was positioned like that, says Begum, because “I really wanted to feel like I was living amongst the trees. When I finally moved in, in November 2019, I thought: how do I capture this change? I had already started doing studies like this during my residency at Tate St Ives. Here I was trying to grasp these moments I feel are slipping through my fingers. I started taking stills not knowing where it was going to go. Just to see what happens. When I was flicking through them, and you flick through fast, I could see the change. So that work developed.”

There is such an ordinary beauty to this work, which you only really appreciate when you have spent time with it – an apt characteristic, given its gestation. Living with that view, she says: “The more I looked at it, the more amazing it became. I love the ivy wrapped around the tree, almost suffocating it. And the council cut the ivy so it’s slowly dying. But it’s still clinging on.”

The film work has lots of potential, she feels. “I’m really excited because that is a medium I haven’t explored before. And I want to do more of it. The last show I had in London was at the Parasol Unit, and I was thinking: does it feel like I’ve moved on? And I think so.”

I agree wholeheartedly.